An extensive study of recent college student performance (surveying over 4,000 students at dozens of different colleges) revealed that today’s college students spend the vast majority of their time socializing or sleeping, that 45 percent of them show no statistically significant gains in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills, and that they face high debt loads and difficult economic transitions (with almost one-third of them living with parents or relatives after graduation). Half of college students did not take any courses that required more than 20 pages of writing the entire semester, and a third did not take any courses that required more than 40 pages of reading per week.

According to a Wall Street Journal analysis:

Freshmen and seniors at about 200 colleges across the U.S. take a little-known test every year to measure how much better they get at learning to think. The results are discouraging. At more than half of schools, at least a third of seniors were unable to make a cohesive argument, assess the quality of evidence in a document or interpret data in a table, The Wall Street Journal found after reviewing the latest results from dozens of public colleges and universities that gave the exam between 2013 and 2016. At some of the most prestigious flagship universities, test results indicate the average graduate shows little or no improvement in critical thinking over four years.

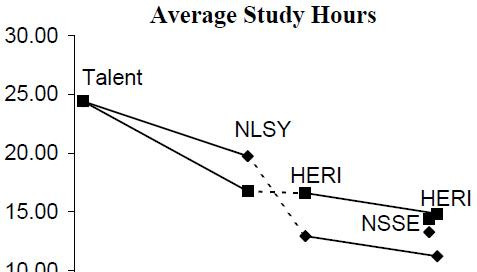

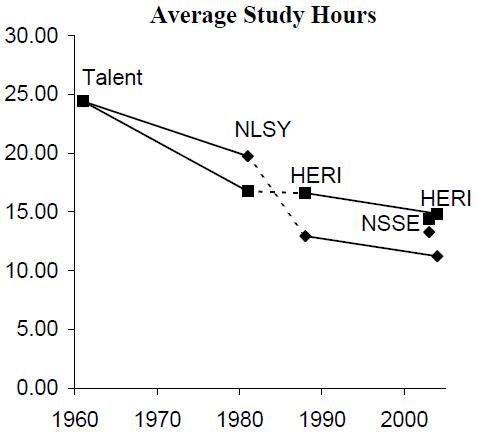

Over the last several decades, the number of hours full-time college students report studying has dropped in half.

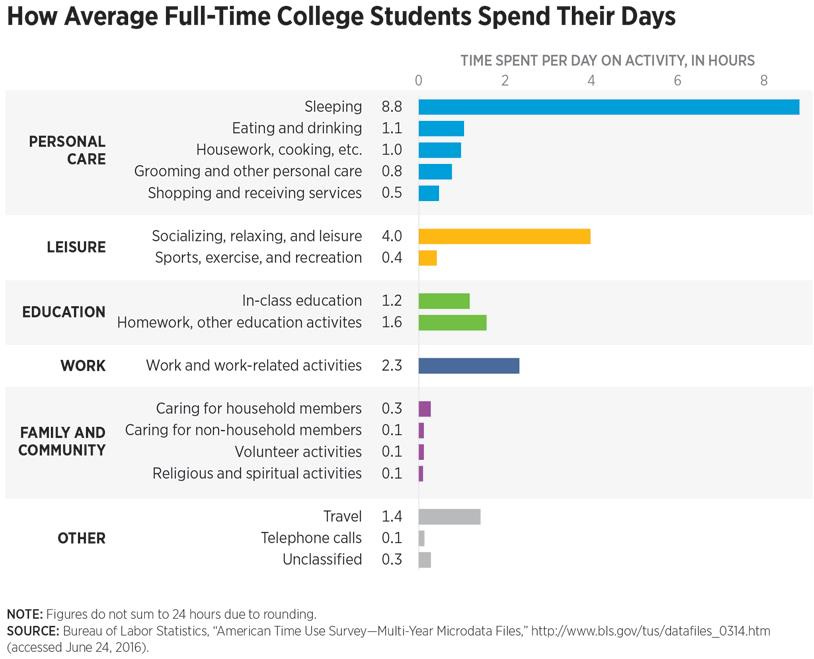

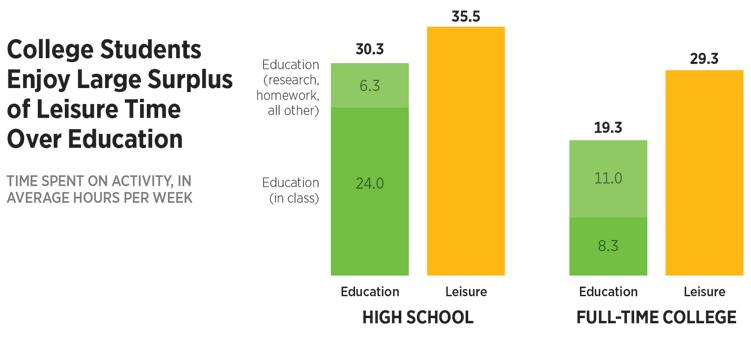

Based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey from 2003-2014, during the academic year, the average full-time college student spent only 2.76 hours per day on all education-related activities, including 1.18 hours in class and 1.53 hours of research and homework, for a total of 19.3 hours per week.

As Frederick Hess and James Fournier report in 2025:

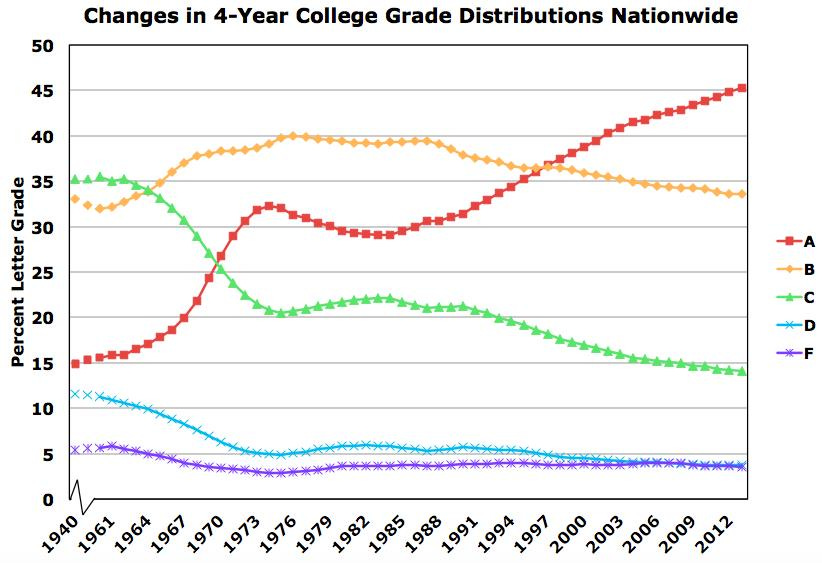

The Chronicle of Higher Education has reported that professors find that their students “struggle to come to class [and] to keep up with the work,” and “they expect professors to work with them, and they assume they’ll pass their classes anyhow.” When the Chronicle asked faculty members about student disengagement, faculty reported that “far fewer students show up to class,” “those who do avoid speaking when possible,” “many skip the readings or the homework,” and “they have trouble remembering what they learned.” The Chronicle has reported that large numbers of students “don’t see the point in doing much work outside of class” and that, to many students, “a 750-word essay feels long.” Students are uncomfortable with once-unremarkable academic expectations. A 2024 Atlantic account reported that today’s faculty are charged with students who aren’t used to reading books, “struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot,” and tell professors that “the reading load feels impossible.” Adam Kotsko, who teaches at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, lamented the decline in his students’ willingness to read. “For most of my career,” wrote Kotsko, “I assigned around 30 pages of reading per class meeting as a baseline expectation … Now students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages.” He insisted that he had “literally never met a professor who did not share [his] experience.”16 Even for students who do their assignments, the Chronicle reported that “their limited experience with reading also means they don’t have the context to understand certain arguments or points of view.” … College culture has been changed by the temptation for professors to make their peace with lowered expectations. During the pandemic, “the nature of academic deadlines changed,” observed Simmons University psychology professor Sarah Rose Cavanagh; as a result, she suggested, pandemic-era accommodations conditioned students to have an “expectation of endless flexibility.” A professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology told the Chronicle that she had resorted to assigning fewer readings and hoping that students would concentrate on those that were “interesting to them.” This proved inadequate, as students still deemed her demands, such as including at least 25 sources in a final research paper, “unreasonable.” Across much of higher education, the Atlantic has reported, faculty say that they feel as though they have no choice but to “assign less reading and lower their expectations.” Students’ own accounts tell a similar tale. In 2024, 74% of first-year students reported being given no assignments of more than 11 pages, while 39% said that they were asked to write nothing longer than five pages. And it is not just first-year students: 51% of seniors in 2024 said that they had completed zero assignments of more than 11 pages during their final year. Yet even as the effort asked of students has gone down, grades have only gone up. At institutions like Harvard and Yale, the mean GPA is 3.7 or higher, and 80% of grades are at least an A-minus. But grade inflation is not just an elite-school problem. Indeed, two decades ago, John Merrow of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching stated: “Students everywhere report that they average only 10–15 hours of academic work outside of class per week and are able to attain ‘B’ or better grade-point averages.” Today, the evidence suggests that grade inflation has proceeded in public and private colleges at approximately the same rate.

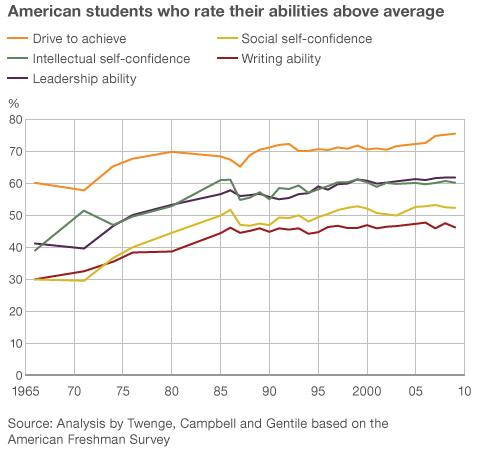

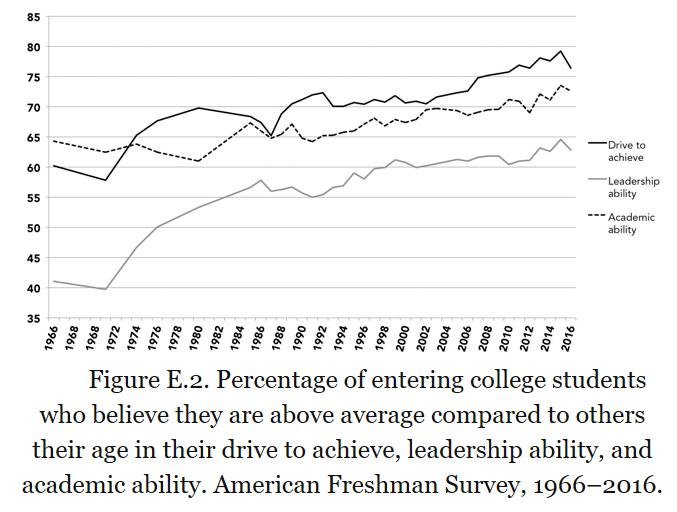

Despite evidence of a lack of learning in college, the Freshman Survey (surveying 9 million young people since 1966) shows that over the past four decades, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of students who describe themselves as being “above average” for academic ability, drive to achieve, mathematical ability, and self-confidence.

More recent data on that topic can be found here.

This increase in students’ self-confidence may be a result in part of rising grade inflation. One survey found that, on average across a wide range of schools, A grades represent 43 percent of all letter grades, an increase of 28 percentage points since 1960 and 12 percentage points since 1988. The first major update in seven years of a database on grade inflation has found that grades continue to rise and that A is the most common grade earned at all kinds of colleges.

As Frederick Hess reports, in November, 2023:

This fall, ACT released a new study tracking high school grades over the past decade—finding a dramatic bout of grade inflation, even as the National Assessment of Educational Progress showed steady declines in academic performance. The results should raise hard questions for those concerned about instructional rigor, sky-high graduation rates, and whether lenient grading policies adopted in the name of equity and student well-being deserve a closer look. At this point, the evidence of grade inflation is incontrovertible. Between 2010 and 2022, student GPAs climbed markedly. According to the ACT study, the average adjusted GPA increased from 3.17 to 3.39 in English and from 3.02 to 3.32 in math. In 2022, more than 89 percent of high schoolers received an A or a B in math, English, social studies, and science. Moreover, the 2019 NAEP High School Transcript Study found that students were getting better grades than those a decade earlier but were learning less. In Los Angeles, the nation’s second largest school district, 83 percent of 6th graders received A, B, or C grades in spring 2022—even though just 27 percent met or exceeded the standards on state and national assessments. Grade inflation isn’t a new phenomenon in American schooling. In 2009, Mark Schneider, now the director of the Institute of Education Sciences, found that, even as the share of students finishing Algebra 2 grew by a third between 1978 and 2000 and math GPAs rose, assessed high school math performance actually fell between 1978 and 2008. Increasingly impressive transcripts and rising grades have yielded less actual student learning.

At the same time, the Society for Human Resource Management reports that 49 percent of managers rate current college graduates as lacking basic writing skills.

Grade inflation is a big problem in that, when kids are getting B’s in class, they often perform one or two grades behind on standardized tests. This results in at least a couple of bad outcomes. First, because parents may focus more on the grade than the standardized test score, they may falsely assume that their child is learning just fine, and as a result not take advantage of very valuable tutoring programs that might allow them to rise to the level at which they actually achieve the learning necessary to fully engage in a job and in society at large. Second, grade inflation also leads to the kind of survey results in which people realize the national education system as a whole is not great, but they still say their school system is just fine, because they are looking at the inflated grades locally for assurance, while thinking of the national test scores when assessing the state of the nation’s educational system. Further, grade inflation in graduate teaching programs leads to fewer teachers actually learning how to convey concepts to students. And when they enter schools, they realize that the need to learn crowd control techniques (which are generally not taught in teaching graduate programs) are initially overwhelming, and can get worse in schools with lax disciplinary programs in which teachers are less able to remove disruptive kids from classrooms. As a result, some teachers never get the gist of being able to convey concepts well because they are so preoccupied with trying to maintain control of their classrooms.

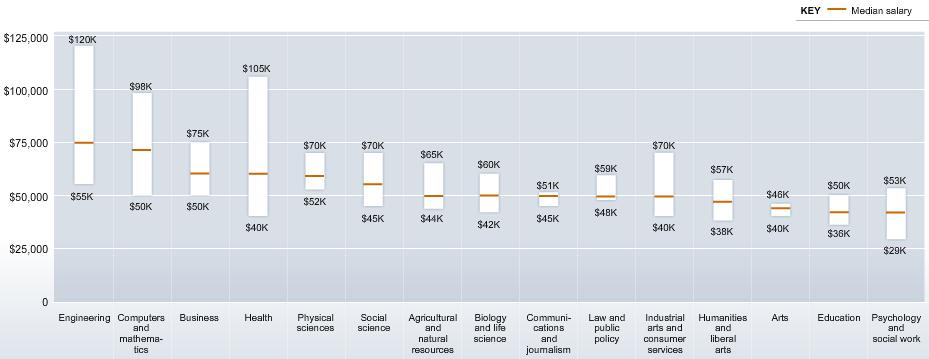

Students are also increasingly graduating from college with degrees (such as in the performing arts, psychology, and communications) that have the least economic potential.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll continue to look at various other measures of the merits of higher education.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12