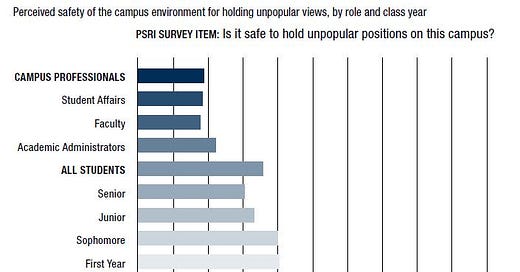

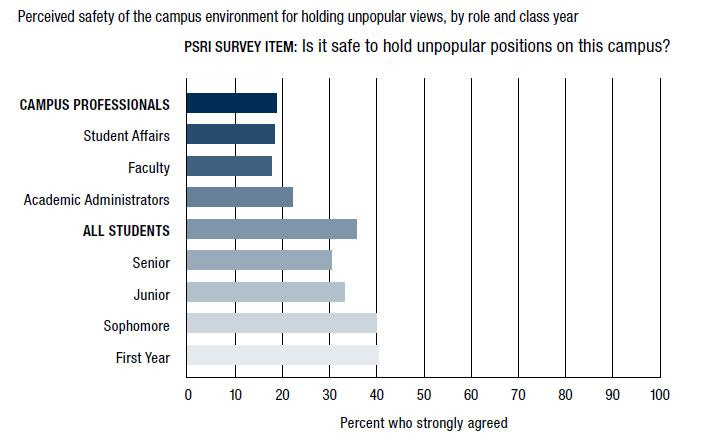

With little diversity of ideas among the faculty, students do not feel comfortable expressing contrary views. Over a decade ago, in 2010, the American Association of Colleges and Universities found in a survey of 24,000 college students that only 36 percent strongly agreed with the statement “it is safe to hold unpopular views on campus.” Of 9,000 campus professionals, only 19 percent strongly agreed with the same statement. And as students progress toward their senior year, they become even more doubtful that it is safe to hold unpopular views on campus.

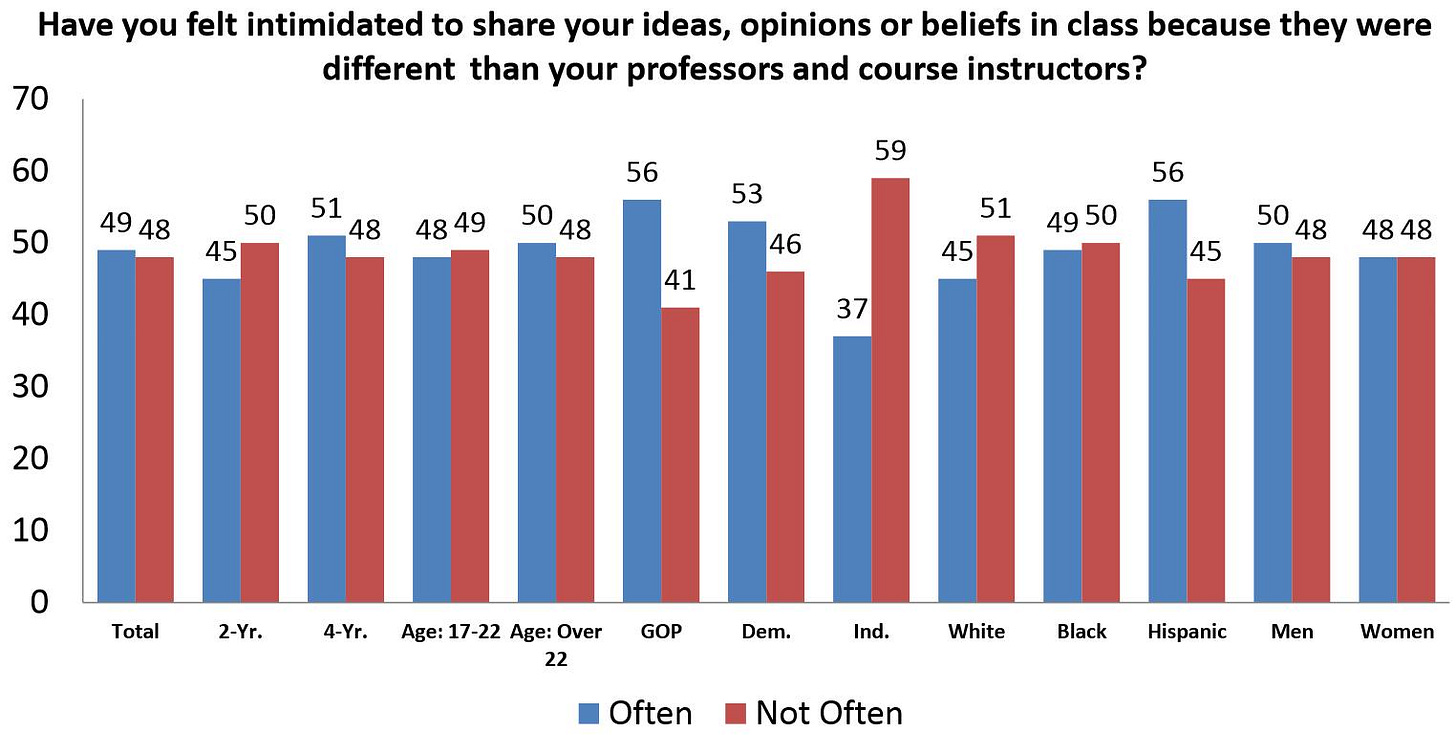

Half of college students report they have “often” felt “intimidated to share your ideas, opinions, or beliefs in class because they were different than your professors and course instructors.”

A November, 2019, Institute of Politics at Harvard University poll found that only about one-third of young Republicans across the nation feel comfortable sharing their political opinions with their professors, compared with Democrats and independents, who polled at 54 percent and 51 percent, respectively, on sharing views with educators.

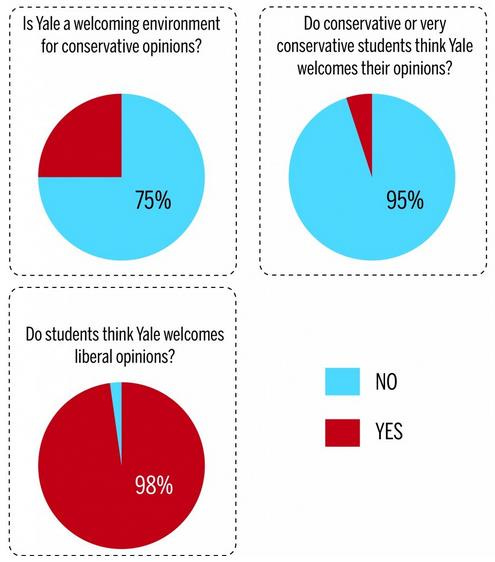

A Yale Daily News survey found that 75 percent of Yale students did not believe Yale was a welcoming environment for conservative opinions, whereas 98 percent believe Yale is welcoming to liberal opinions.

Bias based on political views may also be affecting the award of prestigious scholarships.

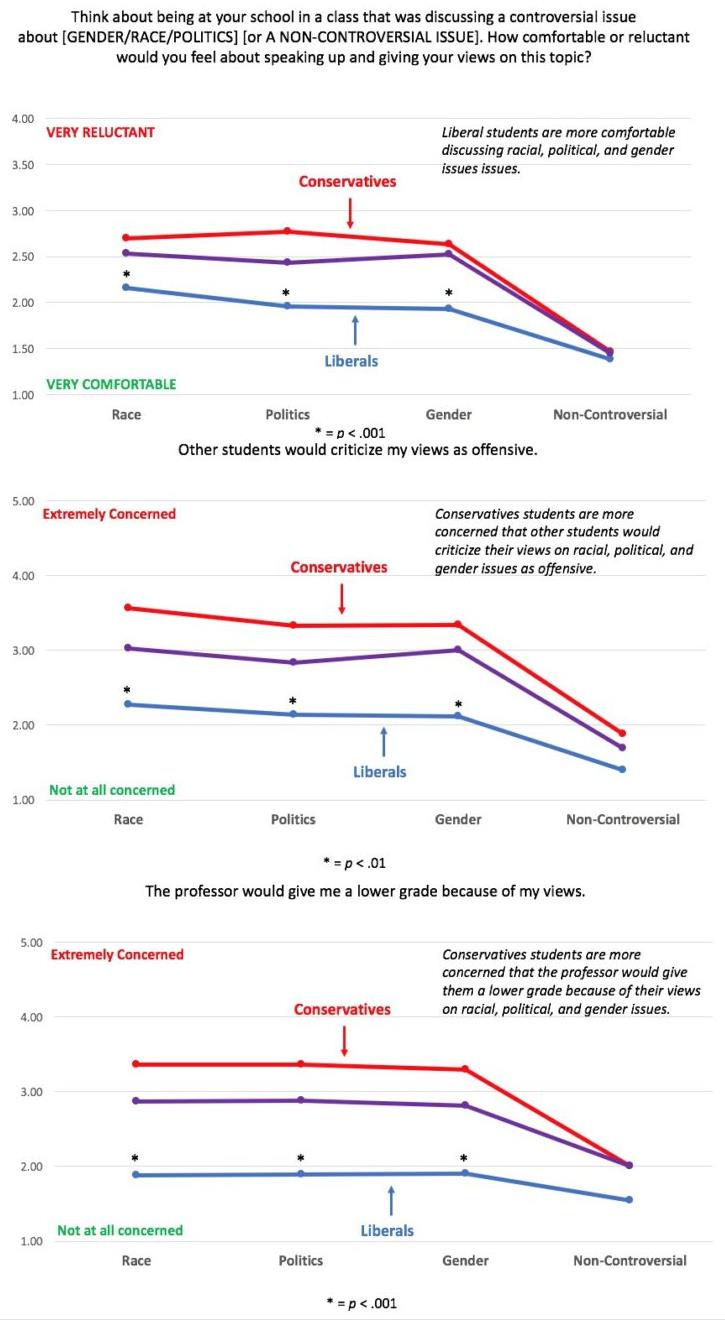

Researchers have developed a “Fearless Speech Index” (now called the “Campus Expression Survey”) survey designed to give professors and administrators a tool to assess the degree to which students feel comfortable (or reluctant) to speak up and offer their opinions in a relatively small class, with 20-30 students. Preliminary results of the FSI survey were described by the researchers as follows:

The FSI is able to identify WHICH students feel intimidated speaking openly, about WHICH topics students are fearful of discussing, and WHY students are fearful of discussing those topics. Our preliminary results suggest that students fear discussing racial issues the most and that their greatest concern is criticism from their peers. Males are not more reluctant to speak up in class than females, but they are more concerned about the social consequences of speech on some topics. The largest group differences were found on politics. Conservatives were far more reluctant to speak up than liberals during class discussions related to race, politics, and gender. They were also more concerned about every negative consequence we asked about. Interestingly, moderates tended to score closer to conservatives than to liberals. Liberals expressed low levels of fear across all topics and consequences.

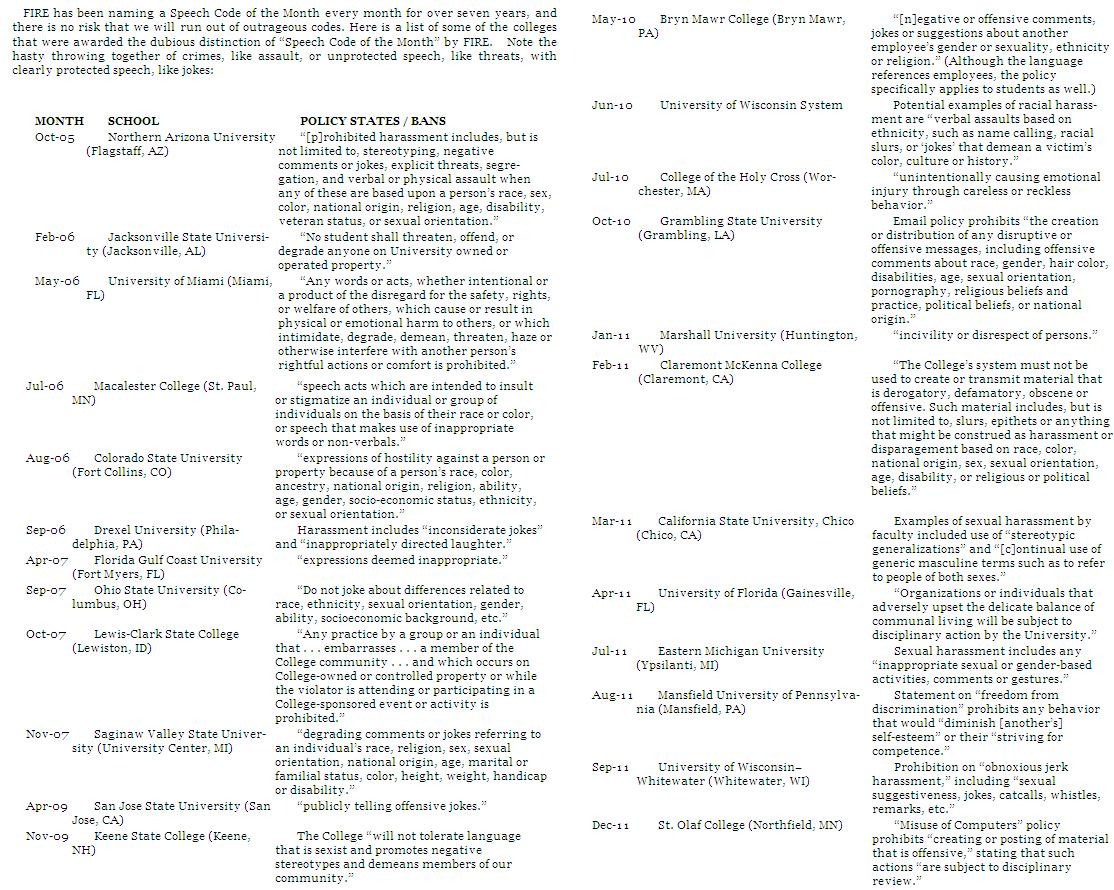

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) tracks speech codes at colleges and universities and has highlighted some examples to illustrate how their vague standards and politically-correct enforcement restricts free speech.

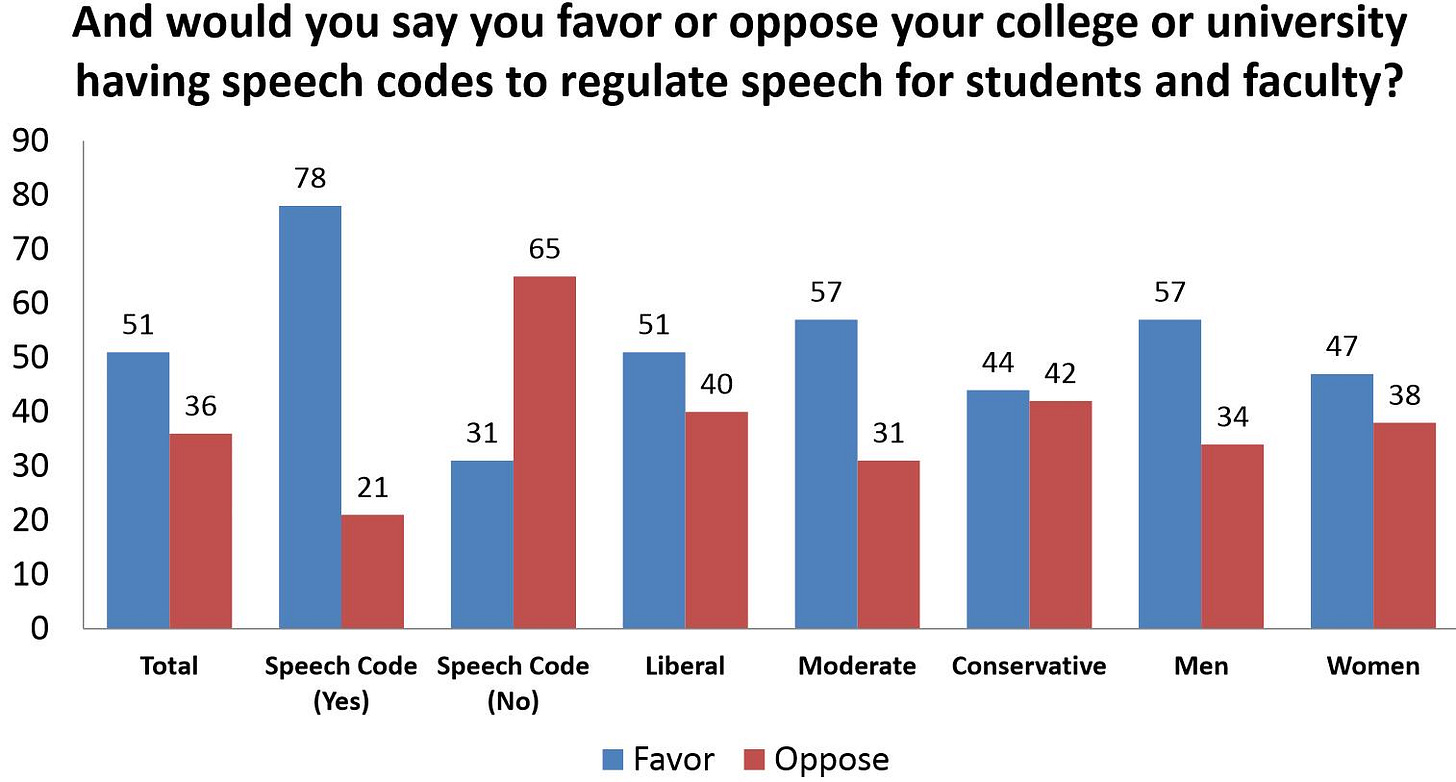

In 2015, a majority of college students supported the imposition of speech codes on campus.

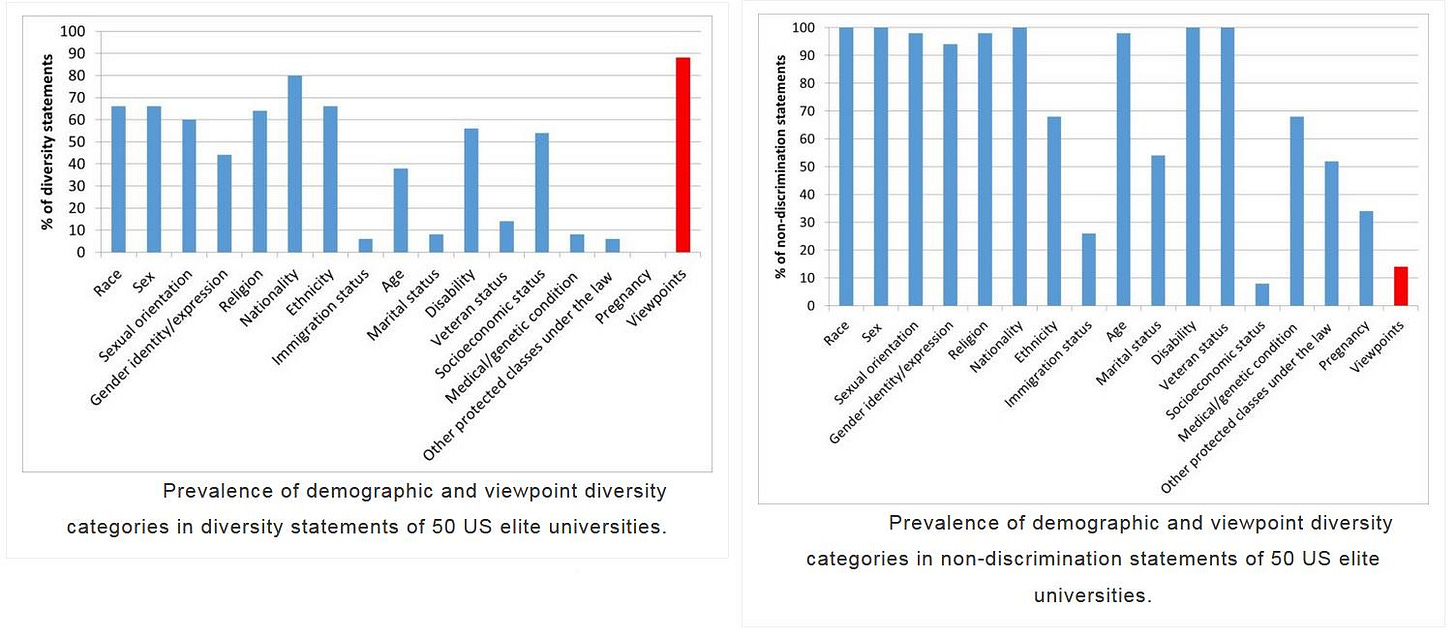

Researchers have also reported that:

We have uncovered a pattern of elite universities in the U.S. overwhelmingly claiming to embrace both demographic and intellectual diversity in their mission and diversity statements. Yet, only 14 percent of the universities studied explicitly protect viewpoint diversity in their nondiscrimination statements while most archetypical types of demographic diversity receive extensive protection. This stark contrast warrants the question of whether an institution can claim to truly value viewpoint diversity, as most of the studied universities say they do in their mission and diversity statements, when there is no actual protection of viewpoint diversity in their nondiscrimination statements.

In 2017, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education released the first-ever nationwide survey of college “Bias Response Teams” (BRTs), discussing the growing threat they pose to free speech on campus. BRTs encourage students to formally report on one another and on faculty members whenever they subjectively perceive that someone’s speech is “biased.” The report identified 232 public and private American colleges and universities that publicly maintained bias response programs during the course of 2016, affecting an estimated 2.8 million students.

Researchers have found that support for free speech correlates with cognitive ability. As they explain:

[W]e again replicated the positive relationship between cognitive ability and supporting freedom of speech for all groups across the ideological spectrum. Moreover, ... we found evidence that higher levels of Intellectual Humility could explain the relationship between cognitive ability and free speech support. In other words, those with higher cognitive ability might support principles of free speech because of their greater independence of intellect and ego, openness to revise their viewpoints, respect for others’ viewpoints, and lack of intellectual overconfidence. The series of studies suggest that cognitive ability is related to support for freedom of speech for groups across the ideological spectrum. These results do not mean that people with higher cognitive abilities are free speech absolutists.... The results do suggest, however, that individuals with higher cognitive ability are more appreciative of the free flow of divergent ideas by groups at various places on the ideological spectrum ... even when these groups voice ideas that they don’t like.

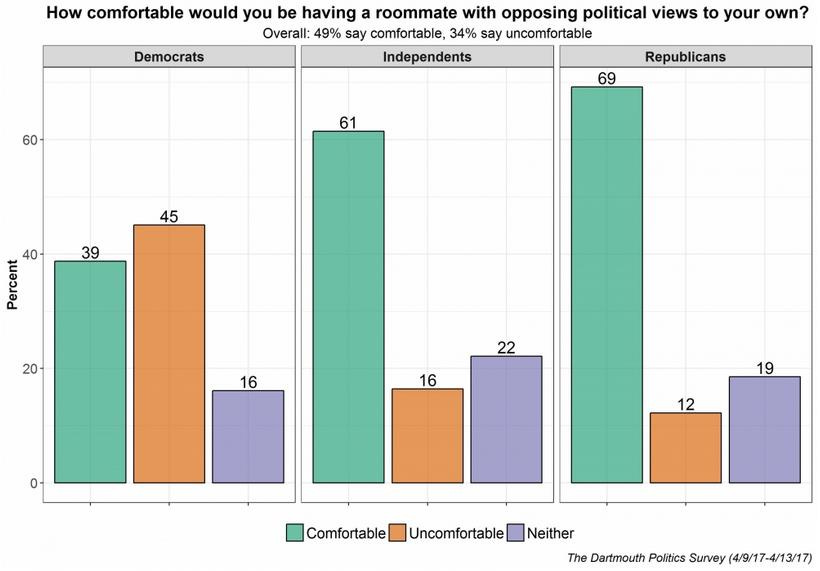

A survey of students at Dartmouth found that while 61 percent of independents and 69 percent of Republicans said they would be comfortable with a roommate of opposing political views, only 39 percent of Democrats said so.

Across three studies, researchers found evidence that dogmatic intolerance was predicted by extreme political beliefs, on both the left and the right. Importantly, they also found evidence that dogmatic intolerance may result in an increased willingness to protest, an increased willingness to curtail the free speech of political opponents, and increased support for antisocial behavior (such as violence) directed towards political opponents.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how ideological insulation in college leads to ideological isolation after graduation.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12