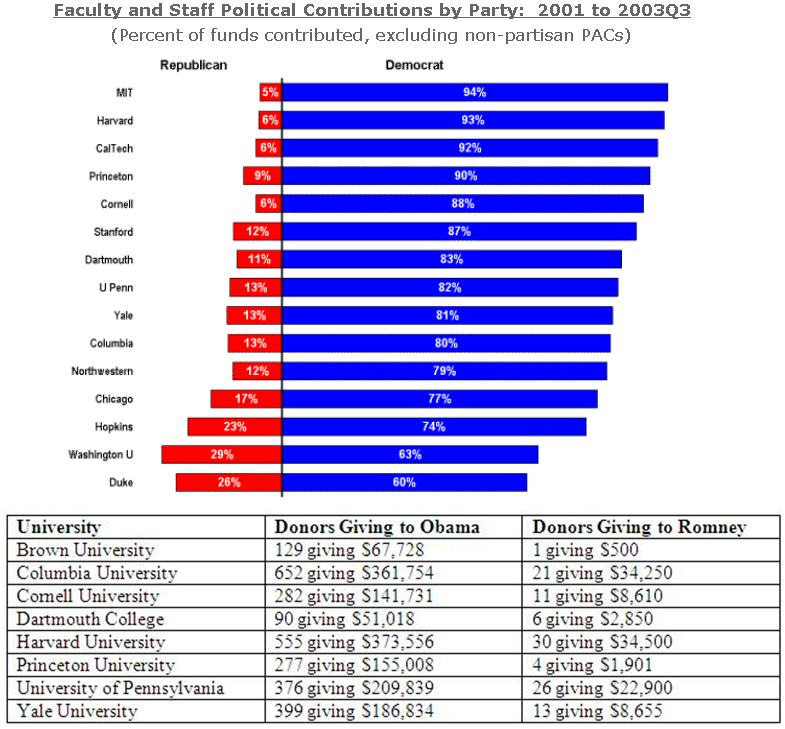

Young adults, many already poorly educated in the public school system, enter universities to be taught by professors who overwhelmingly support large government programs, as exhibited by their political contribution patterns going back decades. Those professors serve on the university hiring boards, and so professors of different political persuasions do not tend to get hired (or they self-select out of the system).

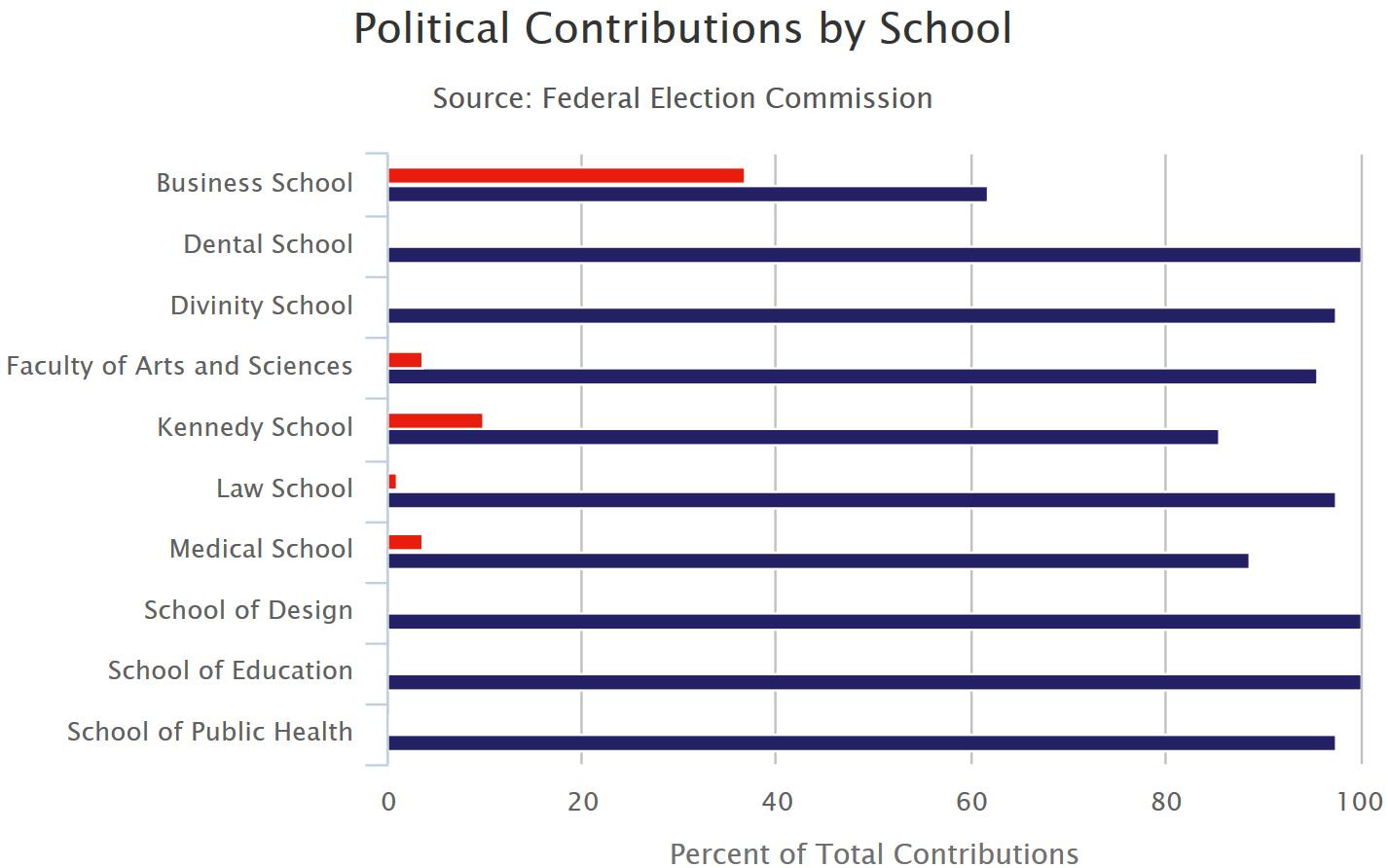

At Harvard’s many schools, an overwhelming majority of faculty political donations go to Democrats (in the chart below, blue lines indicate percent contributions to Democrats, red lines indicate percent contributions to Republicans). At Harvard Law School, 98 percent of faculty political donations go to Democrats.

As the editors of the Harvard Crimson have written:

Startlingly, just around 1.5 percent of respondents to The Crimson news staff’s survey of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences identify as conservative or very conservative, compared to 83.2 percent who identify as liberal or very liberal. These statistics do not reflect America: 35 percent of Americans identify as conservative, 23 times the fraction of the faculty survey’s respondents, and 26 percent identify as liberal. This stark divide has harmful effects on the University’s ability to train our nation’s leaders, and it risks alienating current and potential conservative students. It has also likely contributed to the declining trust of Americans in higher education, which has deleterious effects. Much more work is needed to make this important element of diversity a priority. We believe the University must emphasize hiring professors with diverse beliefs and backgrounds who can challenge prevailing campus ideas through tough ideological conversations.

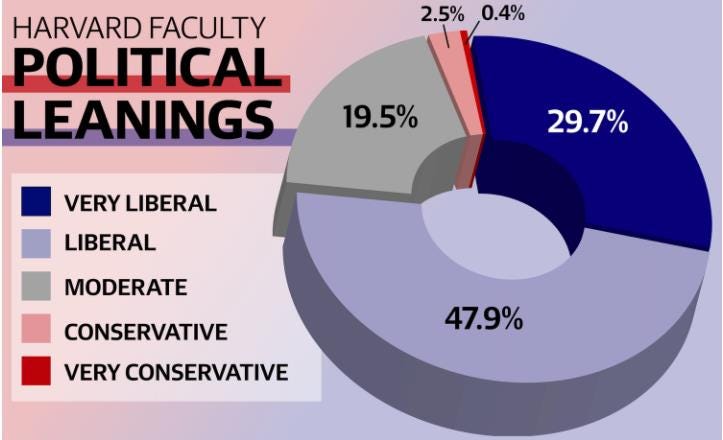

A March, 2020, study of Harvard University faculty finds that only 1.46 percent call themselves conservative. A 2021 survey by the Harvard Crimson newspaper found that “Out of 236 members of the FAS [Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences] who responded to a question on political leanings in The Crimson’s 2021 Faculty Survey, just seven — 3 percent — identified as ‘somewhat’ or ‘very conservative,’ compared to 183 who identified as ‘somewhat’ or ‘very liberal.’”

The report found that 29.7% of faculty consider themselves "very liberal," 47.9% "liberal," 19.5% "moderate," 2.5% "conservative," and 0.4% being "very conservative," according to the student newspaper. In addition, 34% of the faculty surveyed said they support "barring Trump administration officials from appointments within the [Faculty of Arts and Sciences]." The survey also asked faculty if they would "support increasing political diversity among faculty by hiring more conservative-leaning professors?" To this question, only 23.1% of faculty said they would support hiring more conservatives, while 33.61% of faculty saying they would be opposed to hiring more conservatives to increase political diversity. 43.28% of the faculty surveyed said they "neither support nor oppose" hiring more conservative-leaning professors.

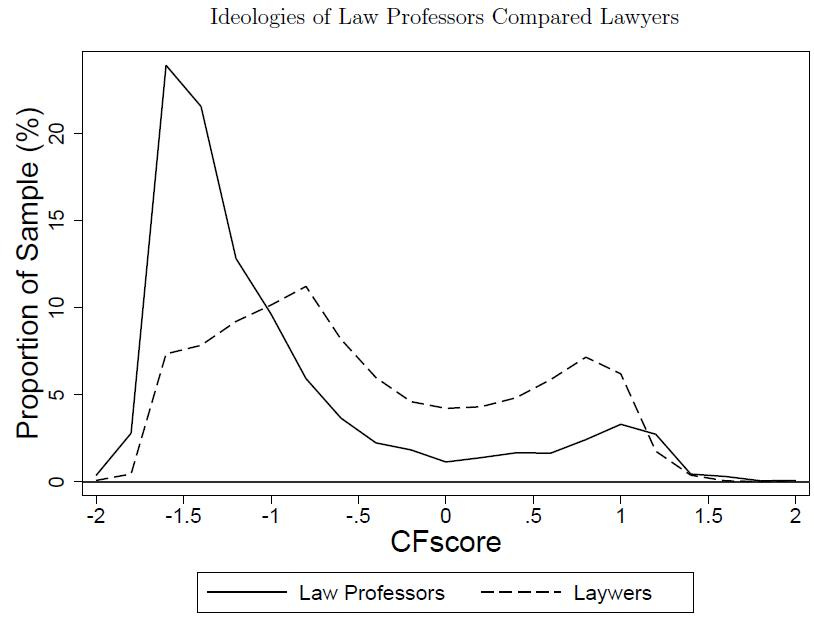

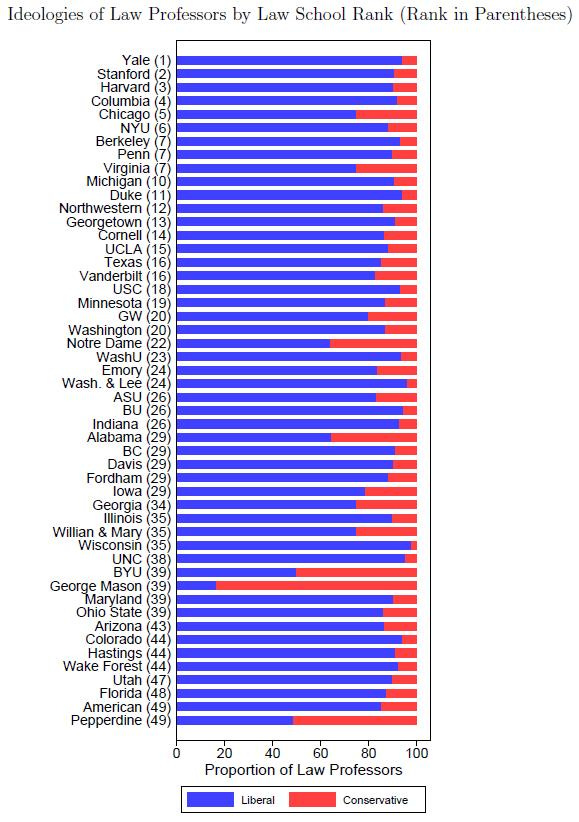

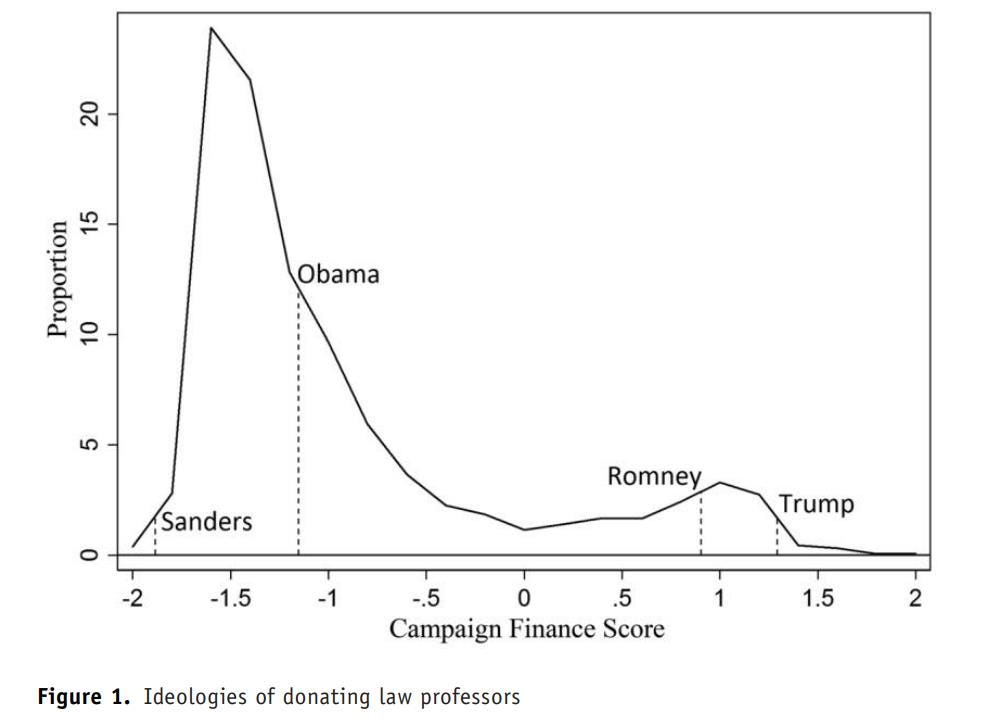

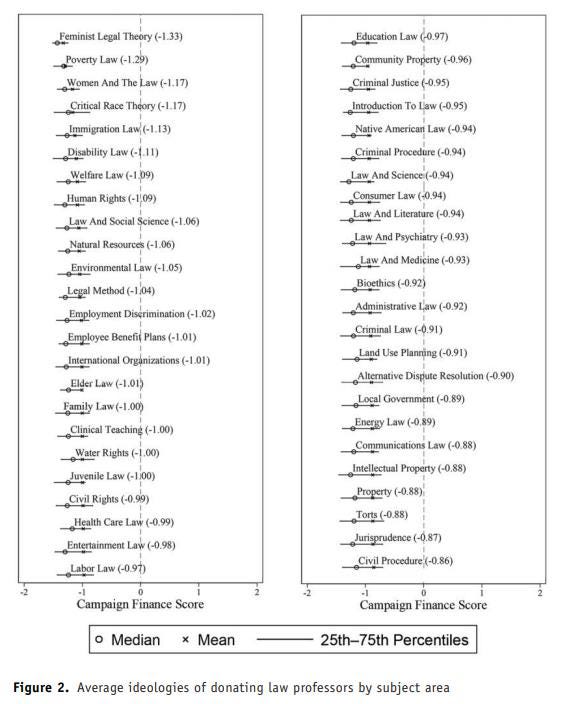

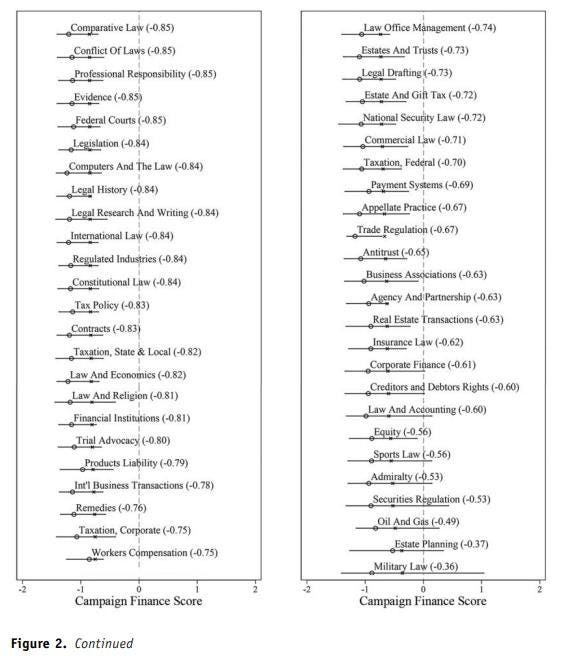

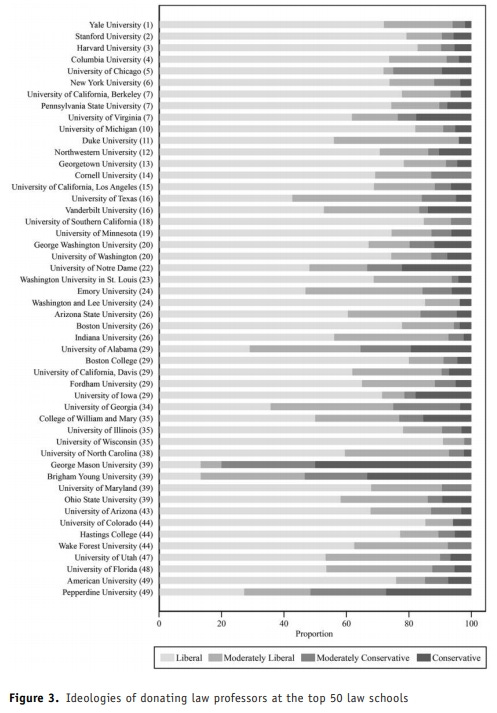

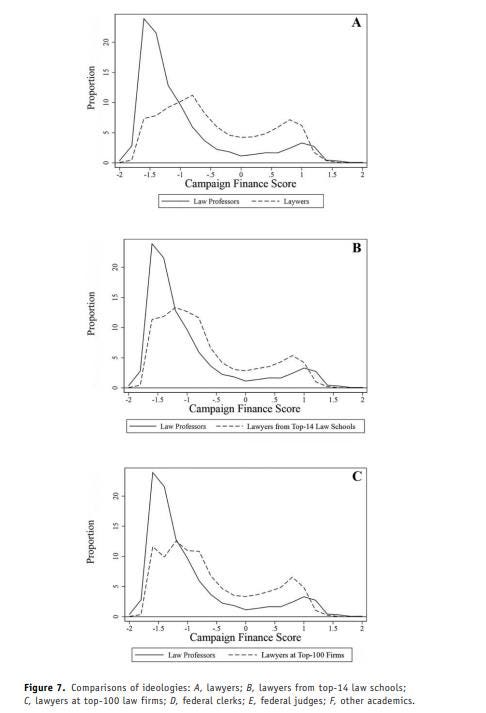

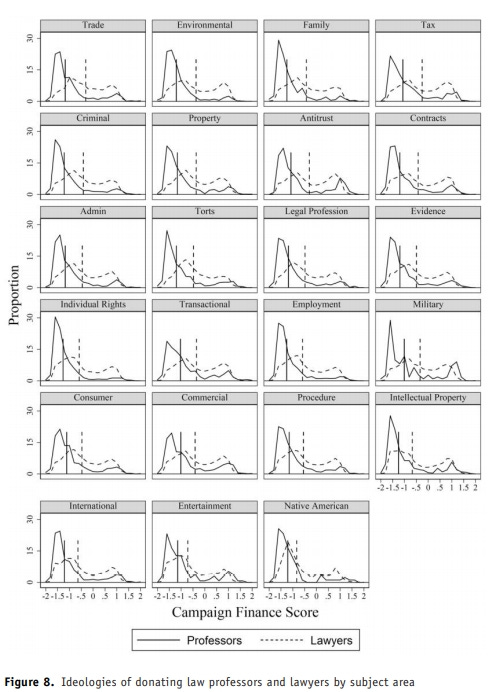

Researchers studying the political views of law professors found the following:

We find that approximately 15% of law professors are conservative and that only approximately one out of every twenty law schools have more conservative law professors than liberal ones. In addition, we find that these patterns vary, with higher-ranked schools having an even smaller presence of conservative law professors. We then compare the ideological balance of the legal academy to that of the legal profession. Compared to the 15% of law professors that are conservative, 35% of lawyers overall are conservative. Law professors are more liberal than graduates of top 14 law schools, lawyers working at the largest law firms, former federal law clerks, and federal judges.

Researchers also found that law professors are significantly more ideologically skewed than the legal profession generally. As the researchers write:

We study the ideological balance of the legal academy and compare it with the ideology of the legal profession more broadly. To do so, we match professors listed in the Association of American Law Schools’ Directory of Law Teachers and lawyers listed in the Martindale-Hubbell directory to a measure of political ideology based on political donations. We find that 15 percent of law professors, compared with 35 percent of lawyers, are conservative. This may not simply be due to differences in their backgrounds: the legal academy is still 11 percentage points more liberal than the legal profession after controlling for several relevant individual characteristics.

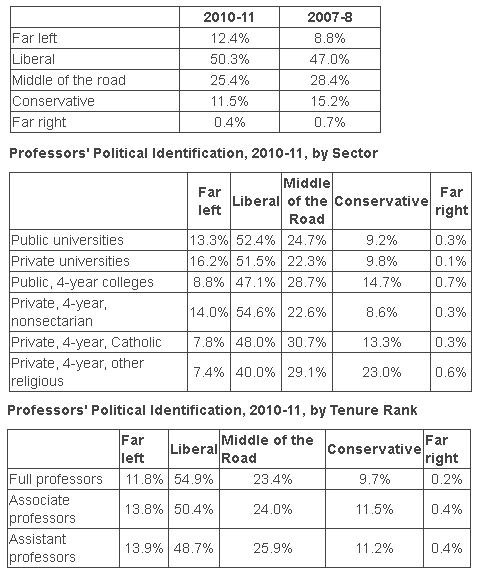

Going back at least a decade, surveys of the views of American professors reflect an extreme lack of diversity in political perspectives among university faculty, especially in the social sciences, the humanities, and political science. For example, almost 18 percent of social science professors identified themselves as Marxist. Other surveys of professors’ political identification show they have shifted even more to the left in recent years.

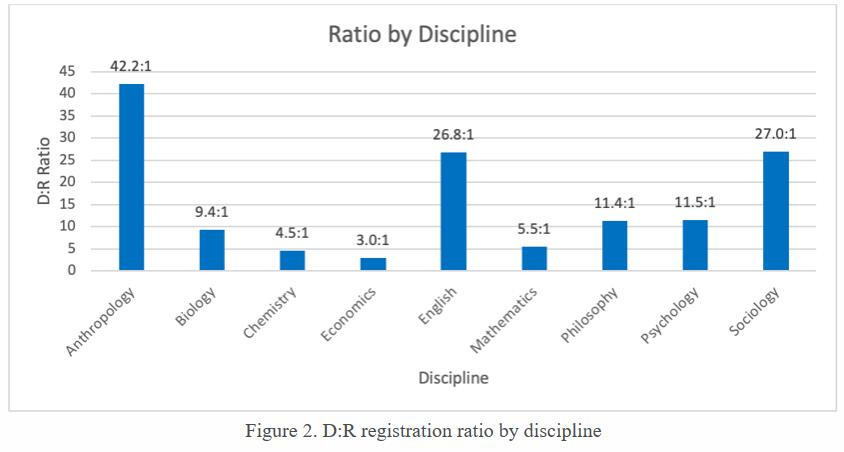

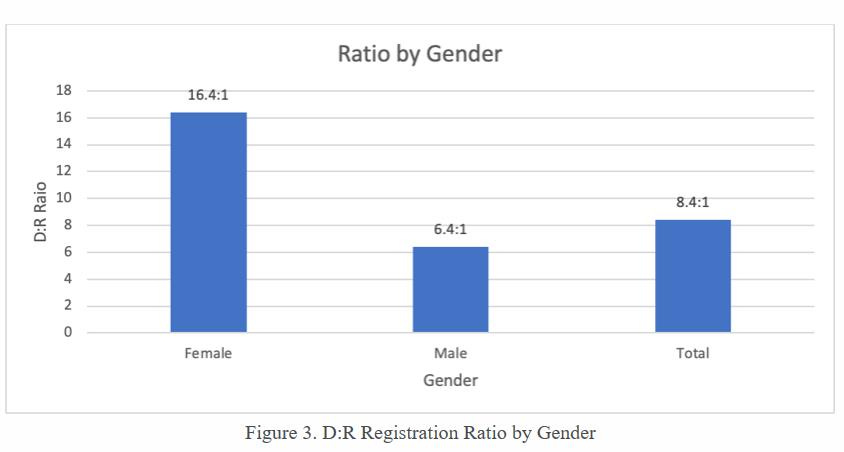

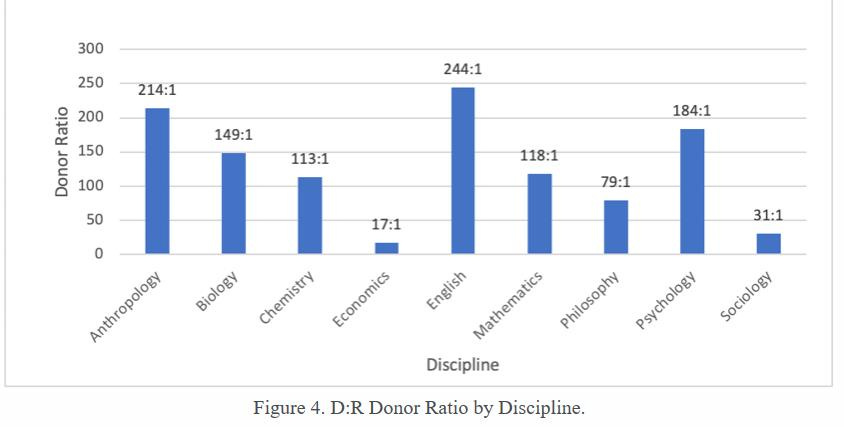

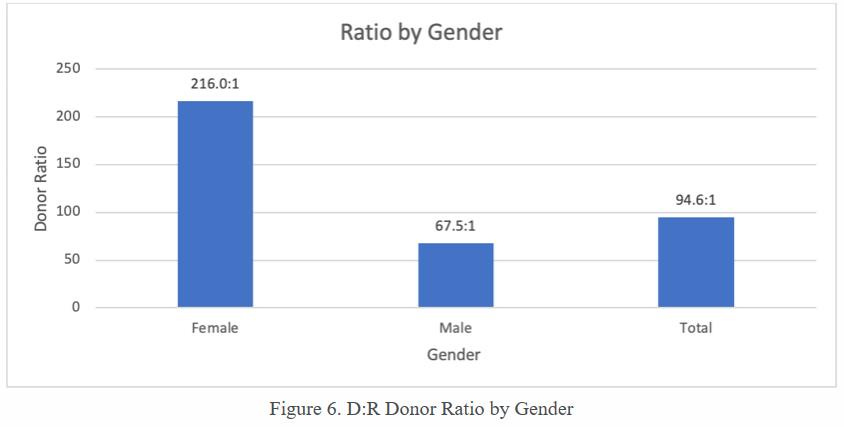

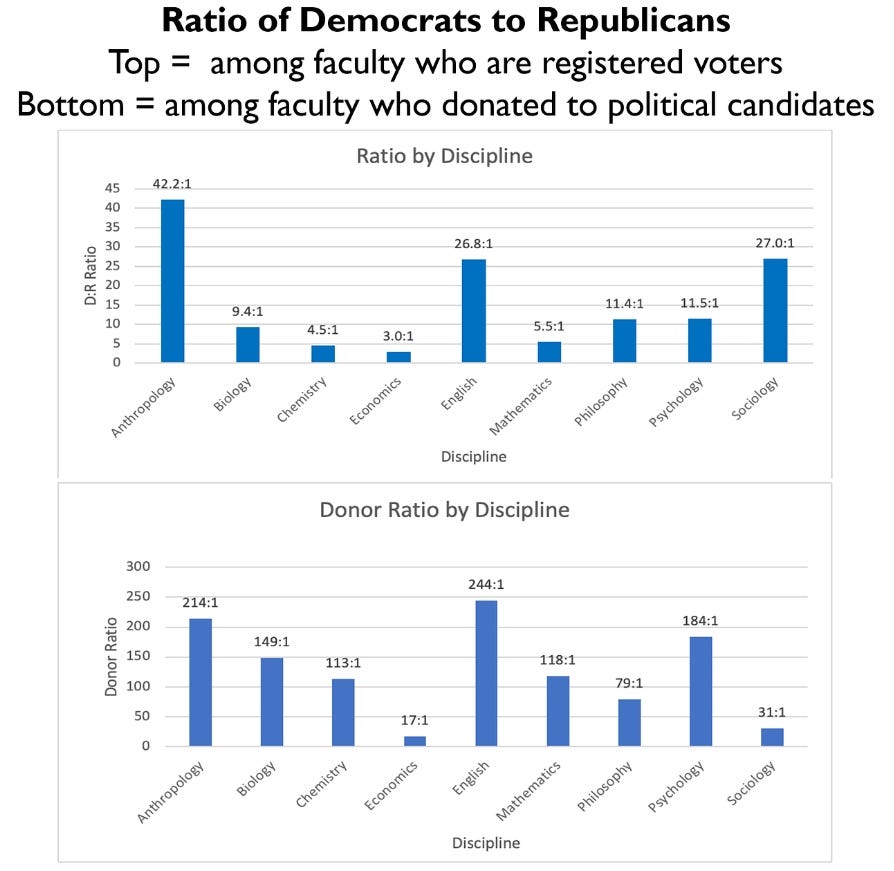

More recent surveys are reviewed and summarized here, with additional information that, regarding voter registration and candidate contributions for a sample of more than 12,000 profs from several of the top schools in each state, 48.4 percent are registered Democrats and 5.7 percent are registered Republicans, a ratio of 8.5:1. Registration ratios ranged from 3:1 in economics departments to 42:1 in anthropology, and tended to be worse at higher-ranked schools. In terms of donations, 2,081 profs gave exclusively to Democrats and only 22 gave exclusively to Republicans, an incredible 95:1 ratio, though the actual dollar amounts were skewed 21:1.

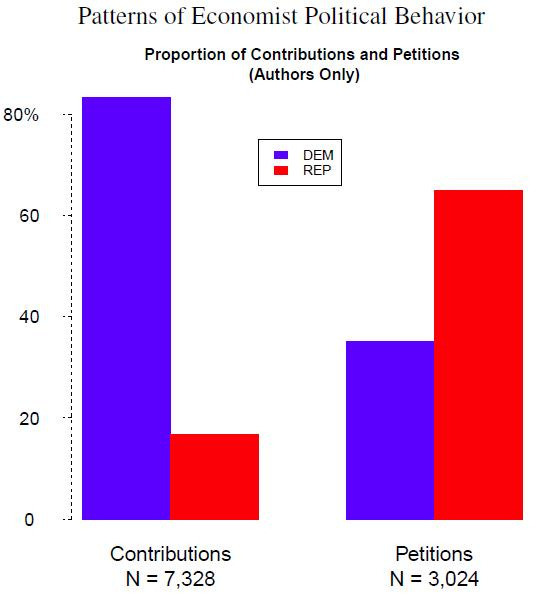

Among economists, over 80 percent make political contributions to Democrats.

Mitchell Langbert at the City University of New York found that:

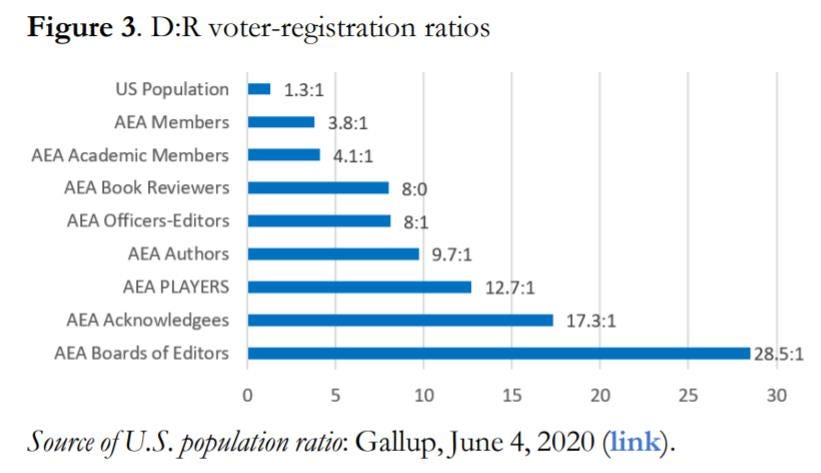

The American Economic Association (AEA) is the premier national organization for professional economics in the United States. This paper shows that the AEA is nearly devoid of Republicans, though many Republicans are found among its membership, which remains open to all who pay the membership dues. I find that the political skew increases up the AEA hierarchy. I use voter registration and political contribution data to examine what I call ‘players’—AEA officers, editors, authors, and acknowledgees (that is, those thanked in published acknowledgments). For AEA players, the Democratic:Republican ratio is 13:1 in voter registrations and 81:1 in political contributors. The most influential professional association of economists in the United States is dominated by people on the political left.

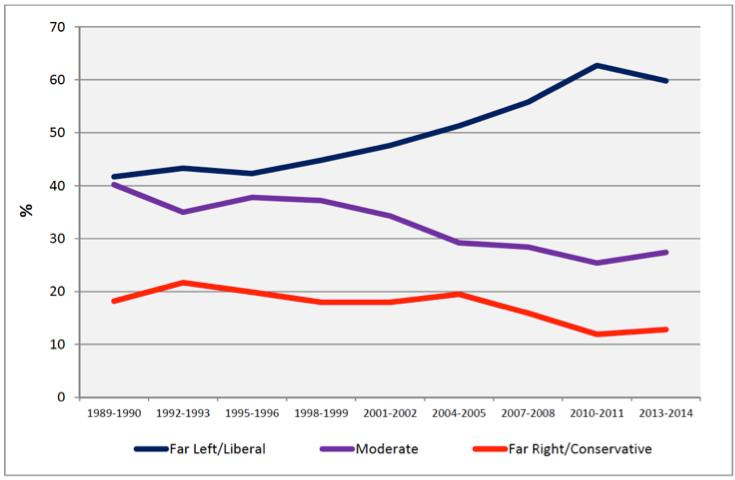

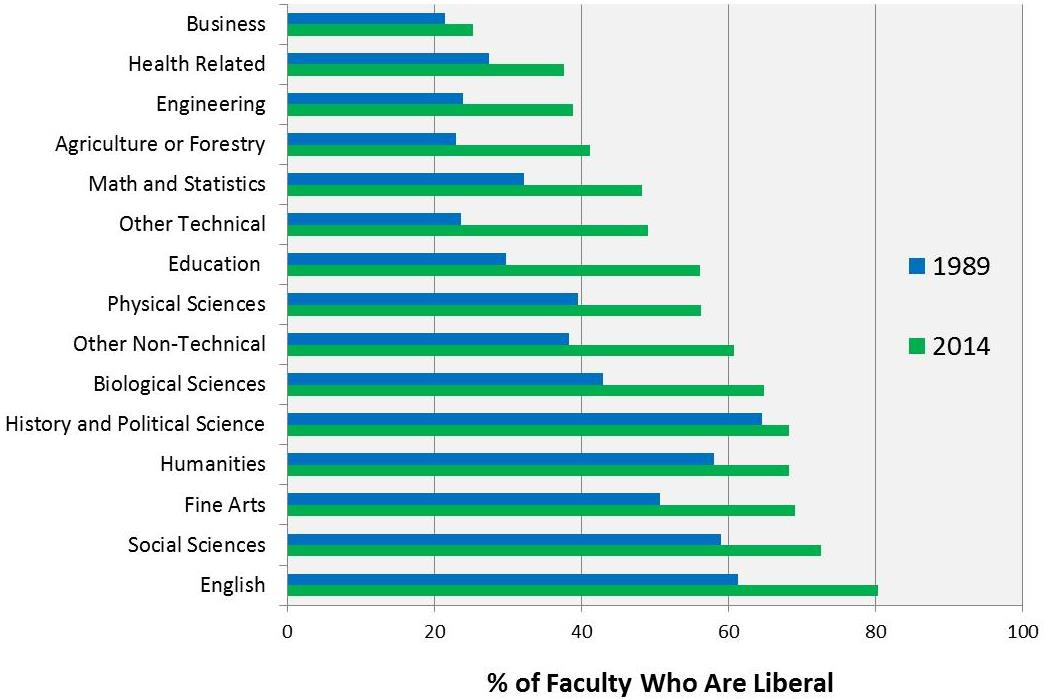

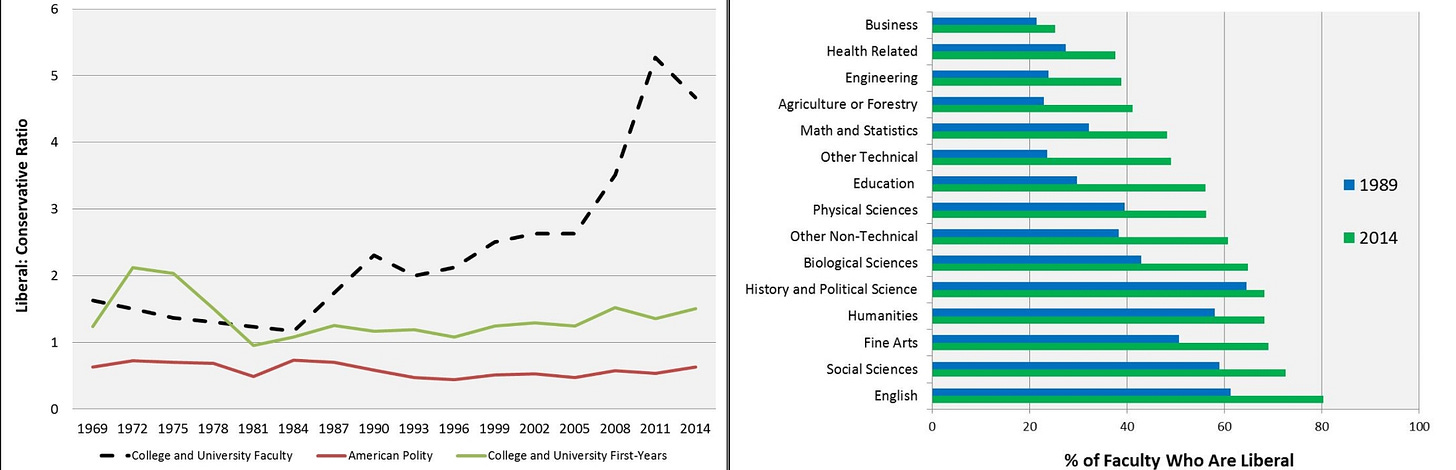

Data from the Higher Education Research Institute, based on a survey of college faculty conducted every other year since 1989, shows that university faculty have become increasingly, lop-sidedly far-left over the last several decades.

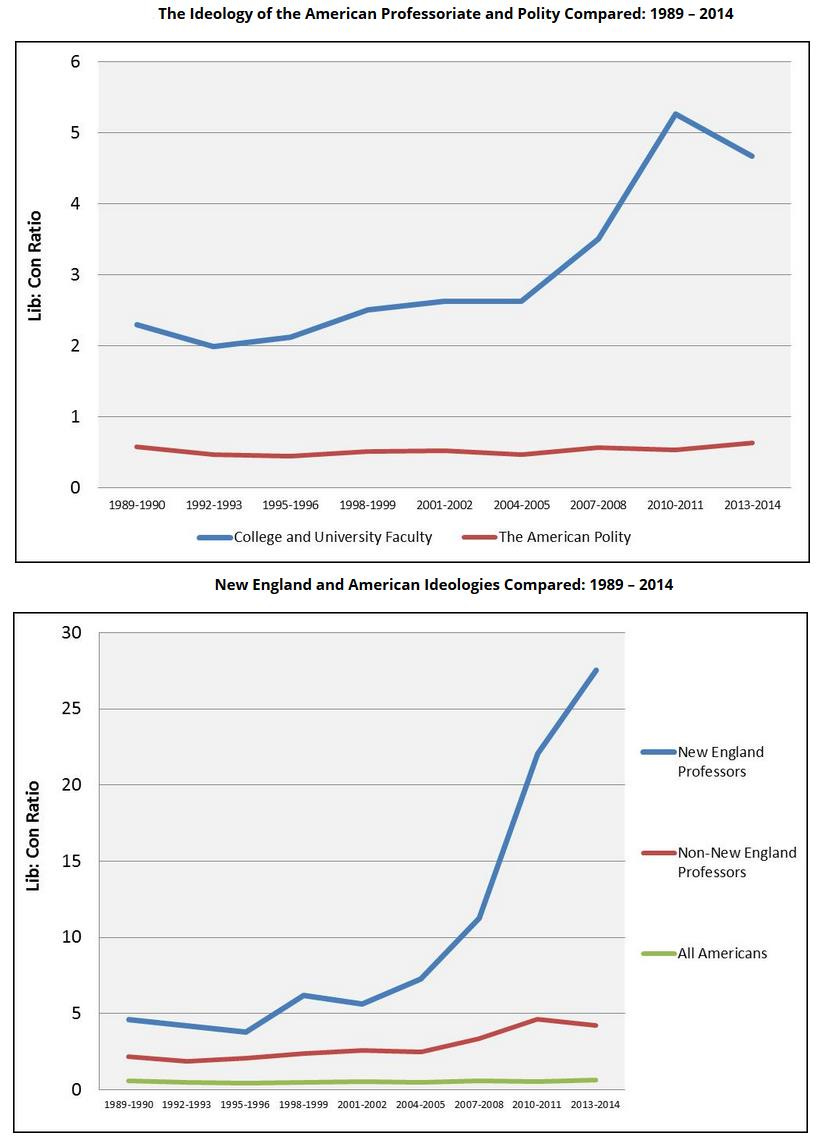

The ideology of American professors has skewed increasingly left, especially in New England.

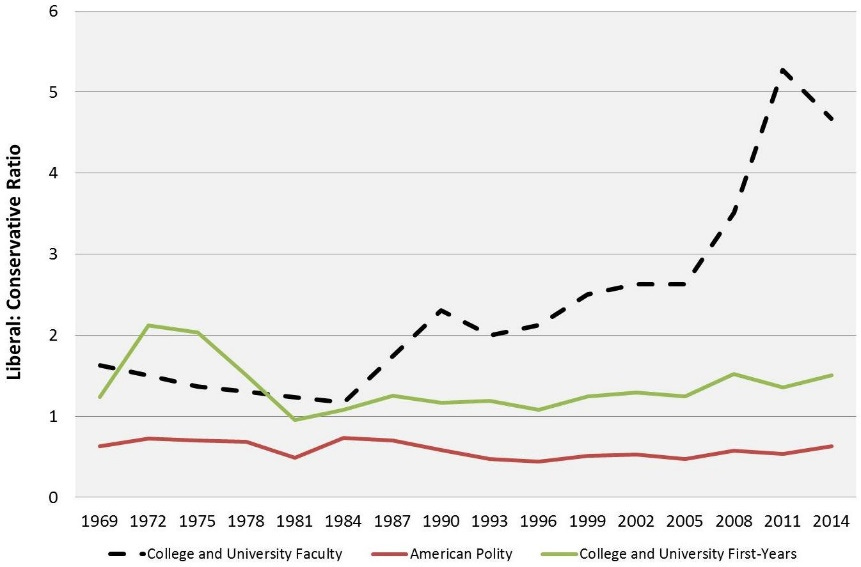

The following chart presents 45 years of data on the political ideologies of college faculty, freshman students, and the American people as a whole, with the y-axis showing left/right ratios measuring the proportion of liberals compared to conservatives in each group.

The leading institutions in higher education – especially those that train future faculty– are located in places far more Democratic than the nation as a whole.

The following chart shows the percentage of liberal-identifying faculty increased across all fields of study but at notably different rates, with the arts, social sciences, and humanities becoming far more liberal than the more technical and pre-professional fields.

Researchers have also surveyed academics and found that conservative academics place higher value on academic rigor and knowledge advancement, and liberal academics place higher value on “social justice” and students’ emotional well-being. As the lead researcher summarized the findings:

Relatively conservative professors valued academic rigor and knowledge advancement more than did relatively liberal professors.

Relatively liberal professors valued social justice and student emotional well-being more so than did relatively conservative professors.

Professors identifying as female also tended to place relative emphasis on social justice and emotional well-being (relative to professors who identified as male).

Business professors placed relative emphasis on knowledge advancement and academic rigor while Education professors placed relative emphasis on social justice and student emotional well-being.

Conservatives are least represented in social science fields. As researchers have found, “The representation quotient for conservatives in social science fields is 0.14, which is significantly lower than any other major population group measured. In other words, the lack of ideological diversity seems to be vastly more pronounced in social research fields than underrepresentation in terms of gender, sexuality, and race.”

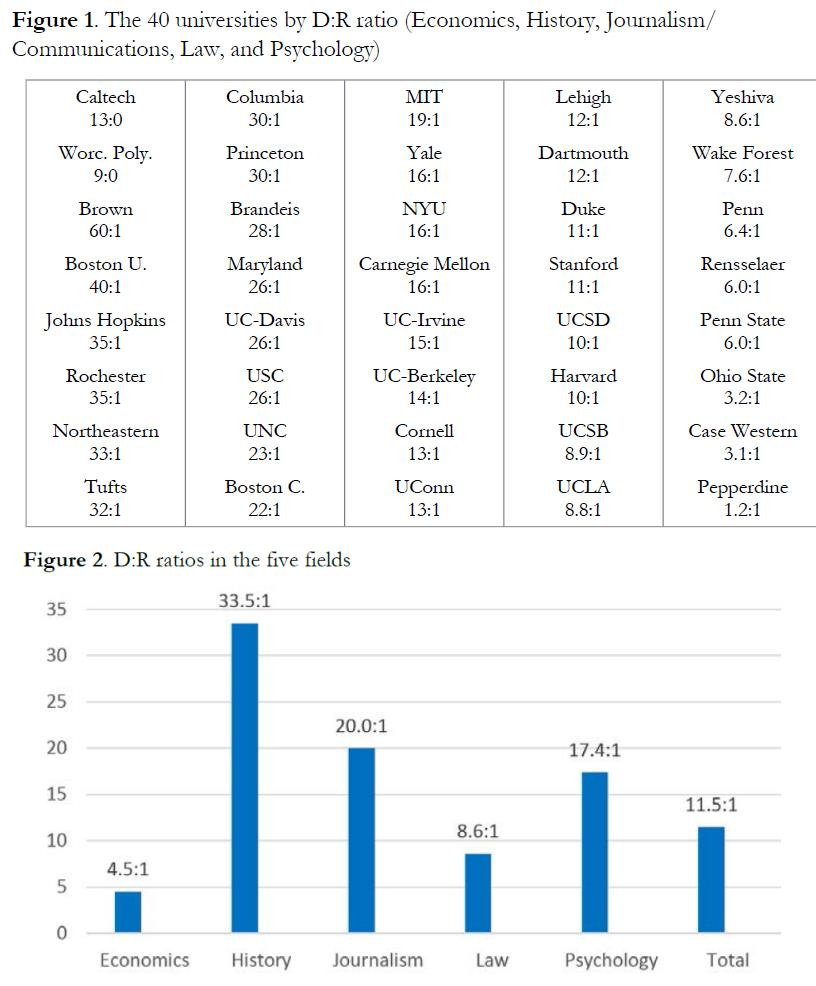

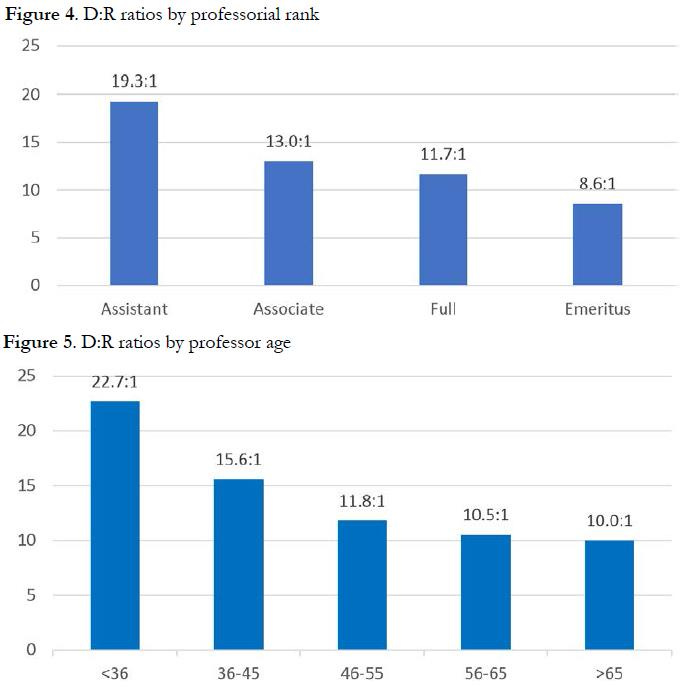

A 2016 study of professors in the fields of economics, history, journalism/communications, law, and psychology, found the following breakdowns of Democratic-to-Republican registration ratios.

The same study found that younger professors (that is, those who will come to dominate higher-education in future years) are even more likely to be registered Democrats than their older colleagues.

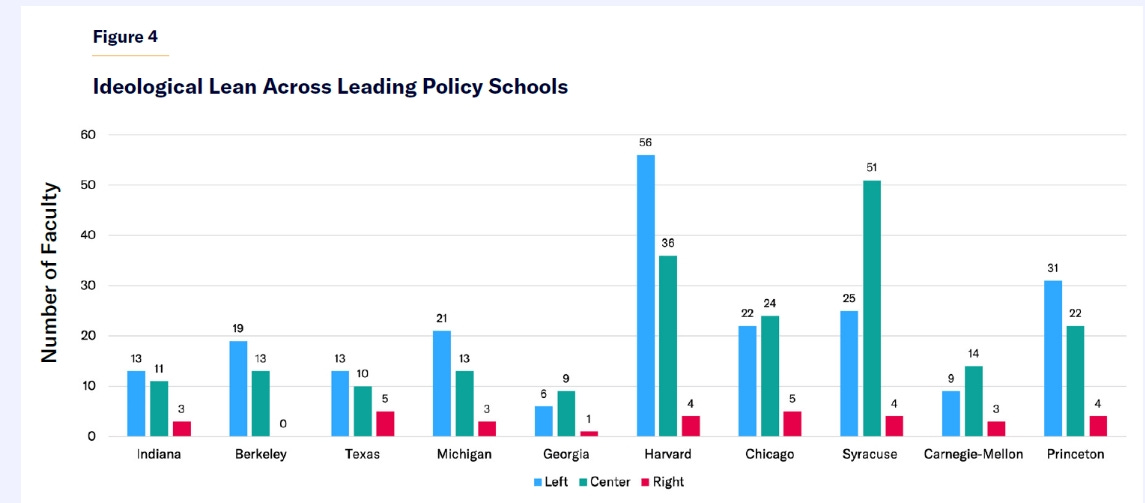

A 20204 survey of the partisan associations of faculty at leading graduate schools on public policy also showed skewed ideological results.

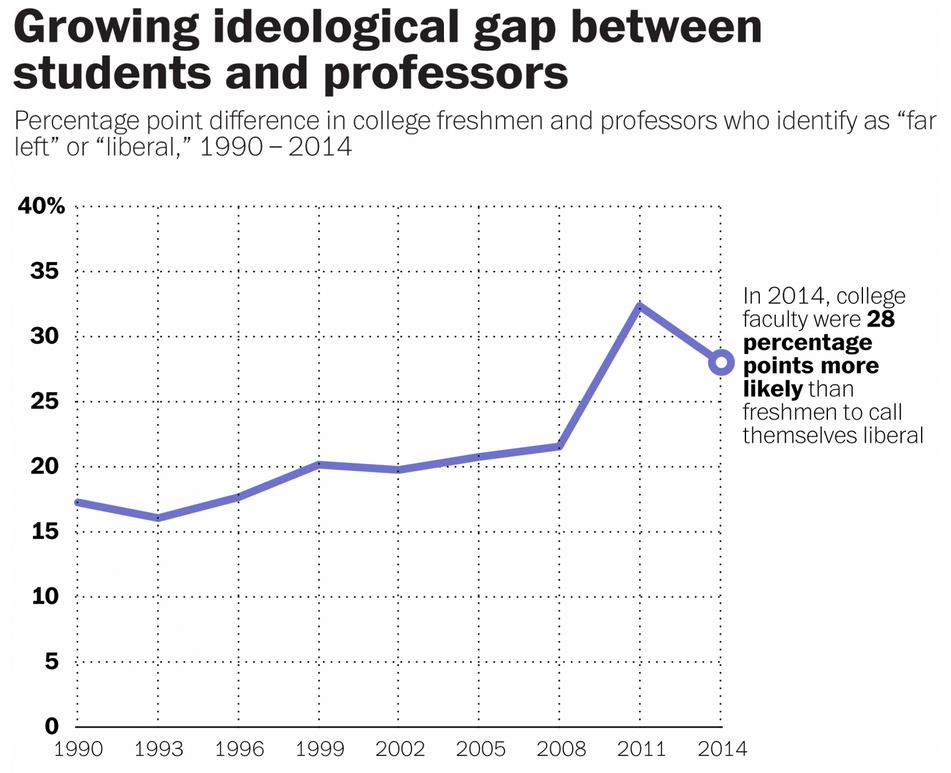

As of 2016, professors were 28 percentage points more likely to describe themselves as “liberal” than the incoming freshman class.

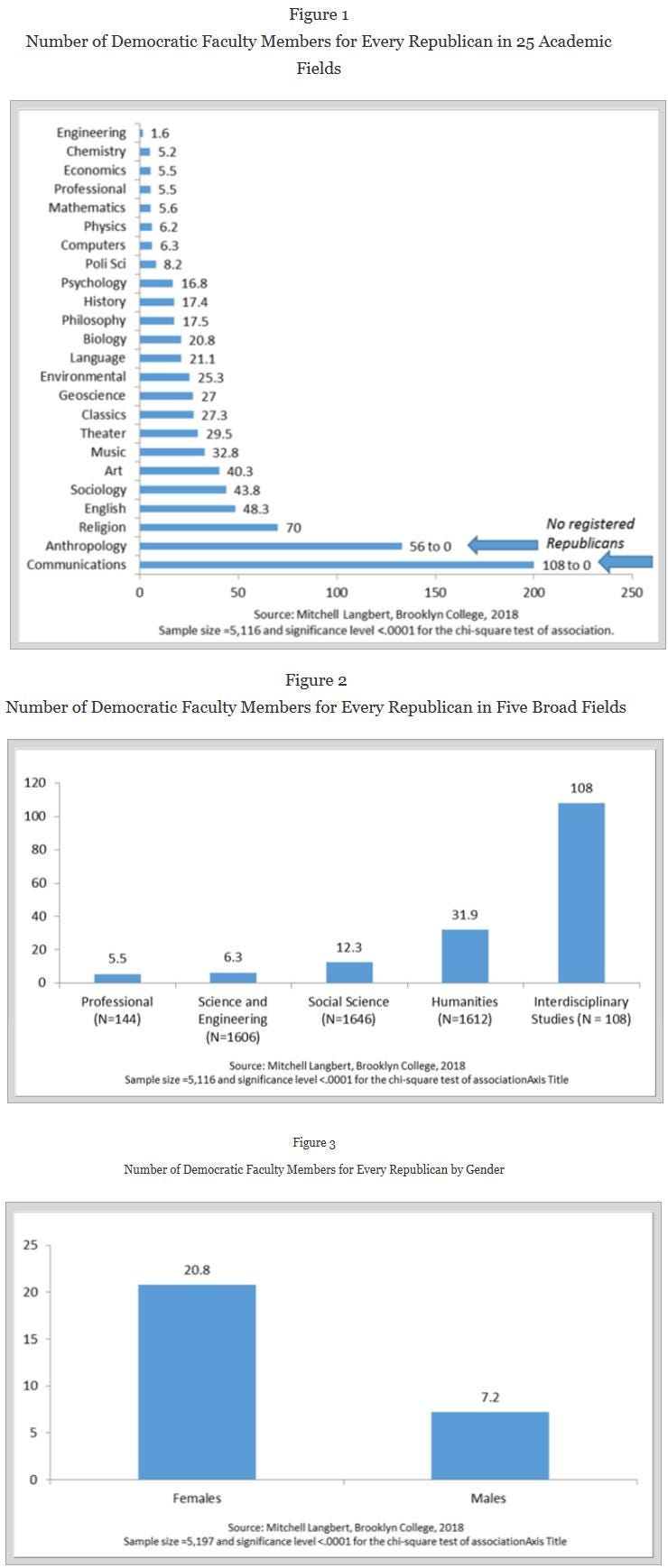

A 2018 study found the following ideological imbalances among college faculty at liberal arts colleges.

As Roger Pielke Jr. writes:

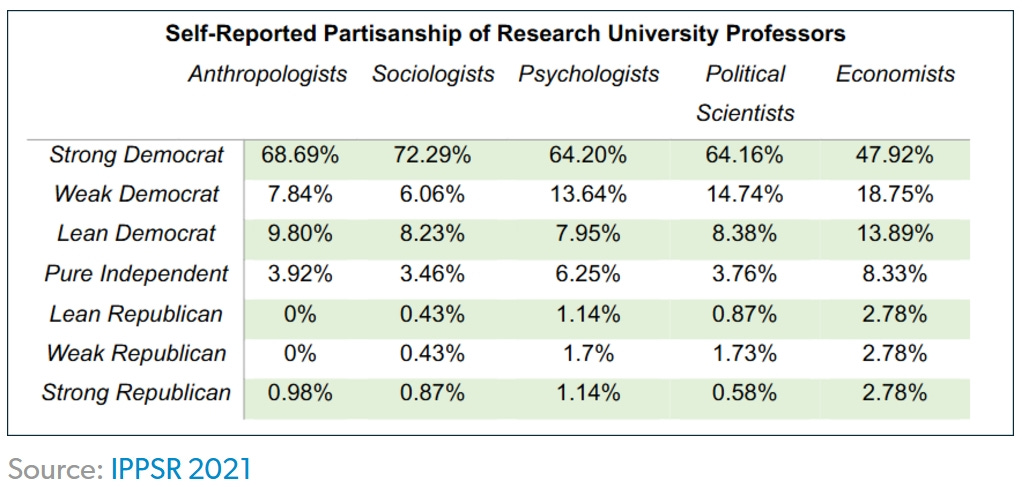

Data on the contemporary politics of professors shows that university faculty as a group hold views very different than most Americans. For instance, a 2020 survey by Joshua Koss, a political scientist at Michigan State University, of tenure-track faculty across 67 universities that are members of the American Association of Universities revealed a striking partisan imbalance across the main social science disciplines, shown in the table below.

A similar survey was published in 2020 by the National Association of Scholars of more than 12,000 tenure-track faculty in the top-ranked universities in each state, based on publicly available information. Results are presented as a ratio of Democrats to Republicans among faculty who were registered voters and who had donated to political candidates. The results show that among those registered to vote by party ID, professors are almost all Democrats. That ratio is even stronger among those who donate to campaigns, as shown in the figure below. Consider that chemistry, a discipline far from partisan politics, has a ratio of 113 donors to Democrats for every one donor to Republicans.

A 2017 analysis by Samuel Abrams of Sarah Lawrence College showed that the political orientation of faculty members had moved to the left over several decades, with a notable increase starting about 2004. In contrast, the ratio of Democrats to Republicans among students and citizens changed little over the same period.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how this sort of groupthink is bad for thinking generally.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12