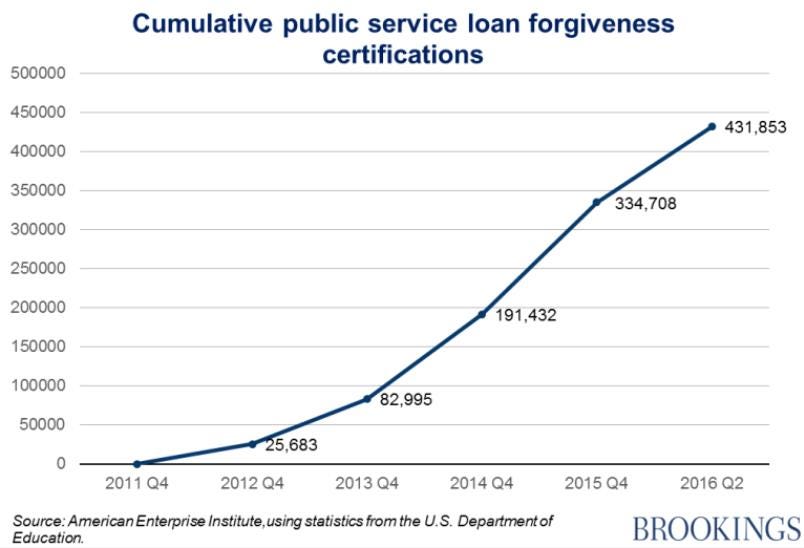

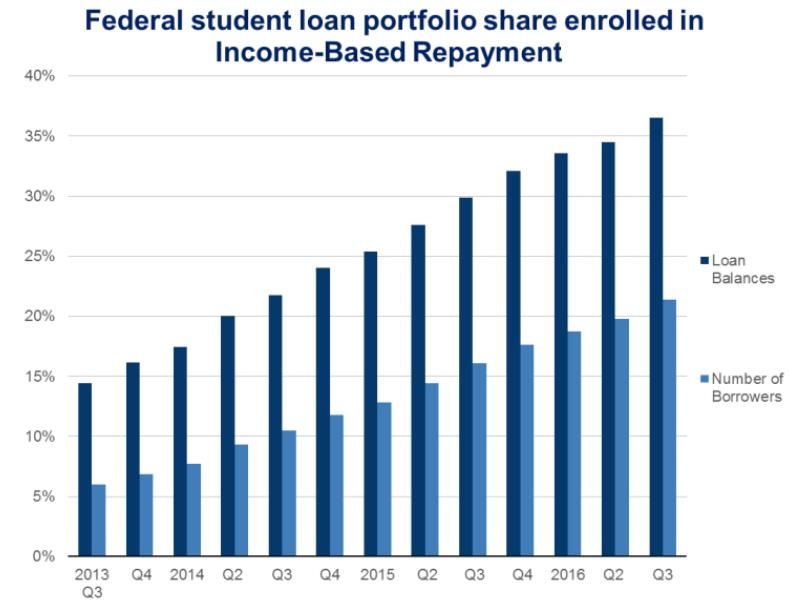

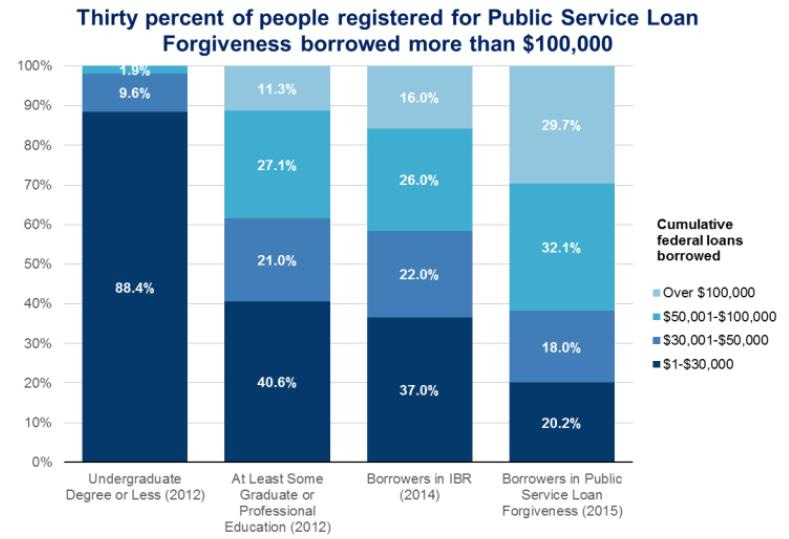

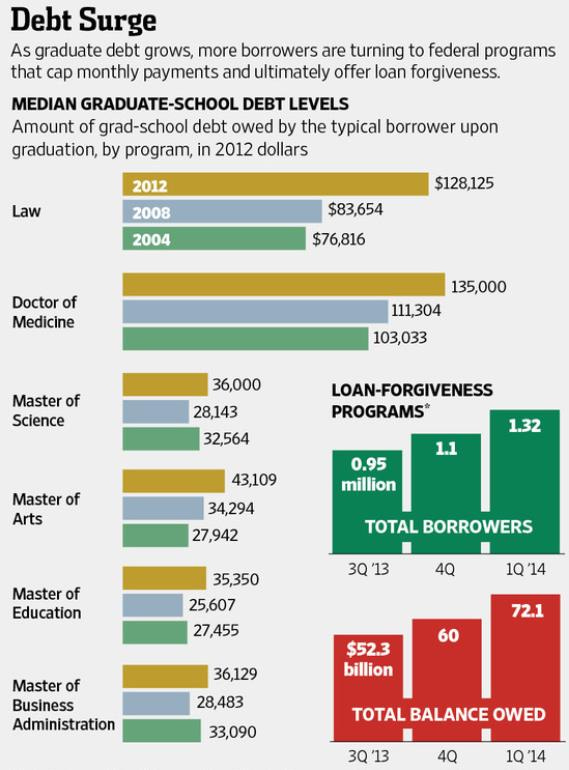

Graduating with significant debt, more and more young people who cannot pay back their loans are becoming further beholden to the government for debt relief through, for example, loan forgiveness programs for students that are conditioned on their going on to work for the government. Under the Obama Administration’s Income-Based Repayment Plan (IBR), monthly loan repayments are capped, and any loans that go unpaid after 10 years are forgiven if the borrower works for the government. That loan forgiveness program is growing rapidly, and the loan balances of those in the program are growing, such that some thirty percent of people taking part in the program have loans over $100,000.

As of 2025, over 12 percent of all student loans were being completely forgiven under this program. As Preston Cooper and Alexander Holt report:

The Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, which fully discharges the student loans of borrowers who work for the government or a nonprofit for 10 years, is one of the most expensive features of the federal role in higher education … PSLF has discharged nearly $80 billion in student loans for 1.1 million borrowers. Another 2.4 million people are working towards PSLF with an aggregate balance of $214 billion, or around one-eighth of the entire federal student loan portfolio. The average PSLF borrower has $74,000 forgiven, and that number appears to be headed upwards. PSLF’s “jackpot” structure—those who qualify have their debts forgiven in full, regardless of how much they borrowed—creates incentives for overborrowing. PSLF mainly benefits graduate borrowers, who can borrow effectively unlimited amounts from the federal government. If a student knows he will receive PSLF, every marginal dollar borrowed simply gets added to the balance that’s eventually forgiven. Colleges have gotten in on the scheme. PSLF encourages schools to raise tuition for programs like social work, and set up new graduate programs of questionable financial value to capture more federal student loan dollars. Some institutions have actively encouraged students to maximize their borrowing in order to squeeze more money out of PSLF.

If one uses the “repayment estimator” available on the Education Department’s website and enters in a borrower with $50,000 in debt earning an adjusted gross income of $40,000, the site calculates the amount of debt the student would have forgiven. Payments over 10 years total $30,168, nowhere near enough to pay the debt, which means such a borrower has $49,832 in principal and accrued interest forgiven. Enter in $100,000 in debt, and the borrower still makes payments of $30,168, but the amount forgiven is $129,832. Under this program, payments are the same if the student borrows $50,000 or $100,000, and federal taxpayers pay for the difference.

The Wall Street Journal explains that when the Congressional Budget Office reviewed the performance of the program, it found that most borrowers weren’t making payments, and whose who were making payments were doing so sporadically and in tiny amounts:

CBO examined a sample of federal student loans that entered repayment between July 2009 and June 2013 to measure the extent borrowers were making progress on repaying their debt before the three-and-a-half years of pandemic forbearance. Short conclusion: They weren’t. During the first six years after borrowers were supposed to begin making payments, CBO estimates that loans were in repayment status for only 45% of the time—about 32 months. Borrowers weren’t making payments for most of that time because they were either in default, forbearance or deferment. It gets worse. CBO says “borrowers made payments greater than $10 in only 38 percent of the months” in which a payment was due. That means that even most borrowers who were making payments were doing so inconsistently and often in token amounts.

(President Obama’s proposal to create a federal ratings system for colleges did not include any measures of whether students are actually learning in college. Instead, the ratings system focused on graduation rates and increasing the number of students with scholarships or government loans (thereby basing future federal aid on the use of current federal aid). During the Trump Administration, however, the Department of Education made available on a website information that will help people get a better idea of what they are buying before they begin writing large tuition checks. The website, CollegeScorecard.ed.gov, now offers a much fuller picture that gives students more ways to compare colleges. A student choosing her field of study at, say, Iowa State might want to know that while a civil engineering major can look forward to earning $60,700 in the first year after graduation, the salary drops to $30,600 for history. Or compare the median monthly earnings and monthly loan payments for, say, computer science at Duke ($8,300/$82), at Rutgers ($5,858/$221) and at Florida State ($4,233/$231). They can do the same for the debt students compile before they graduate.)

Graduate borrowers opting for federal loans over private loans did so even though over 60 percent of the borrowers could obtain a private loan with a lower interest rate than those on federal loans, saving them at least $4,100 over the life of their loans. Graduate students opt for federal loans with higher interest rates because of other benefits the loans provide, specifically the income-based repayment program (IBR). IBR allows borrowers to make payments set at a low share of their incomes with the potential for loan forgiveness after 10 or 20 years of payments.

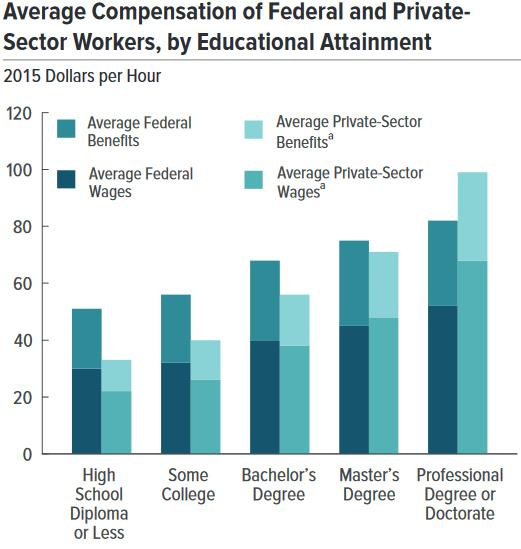

This federal loan forgiveness program for working for the public sector exists even though federal workers tend to make significantly more than what their private counterparts make.

The student loan program that already exists is in many ways more generous than the TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) that bailed out failed financial institutions. (As Jason Delisle has written: Banks that received loans through TARP paid the government 5 percent interest for five years and 9 percent thereafter. The student-loan program today lends to undergraduates at 4.5 percent for up to a 30-year term. Most graduate students pay 6 percent … The same is true when we compare how much debt is written off. Under TARP the government cancelled $19 billion of loans made to financial companies. While that is nothing to sneeze at, the forgiveness benefits in the Income-Based Repayment program for federal student loans are projected to cost taxpayers a similar amount ($14 billion) every year. If Wall Street received something students didn’t, it is not in these numbers.”)

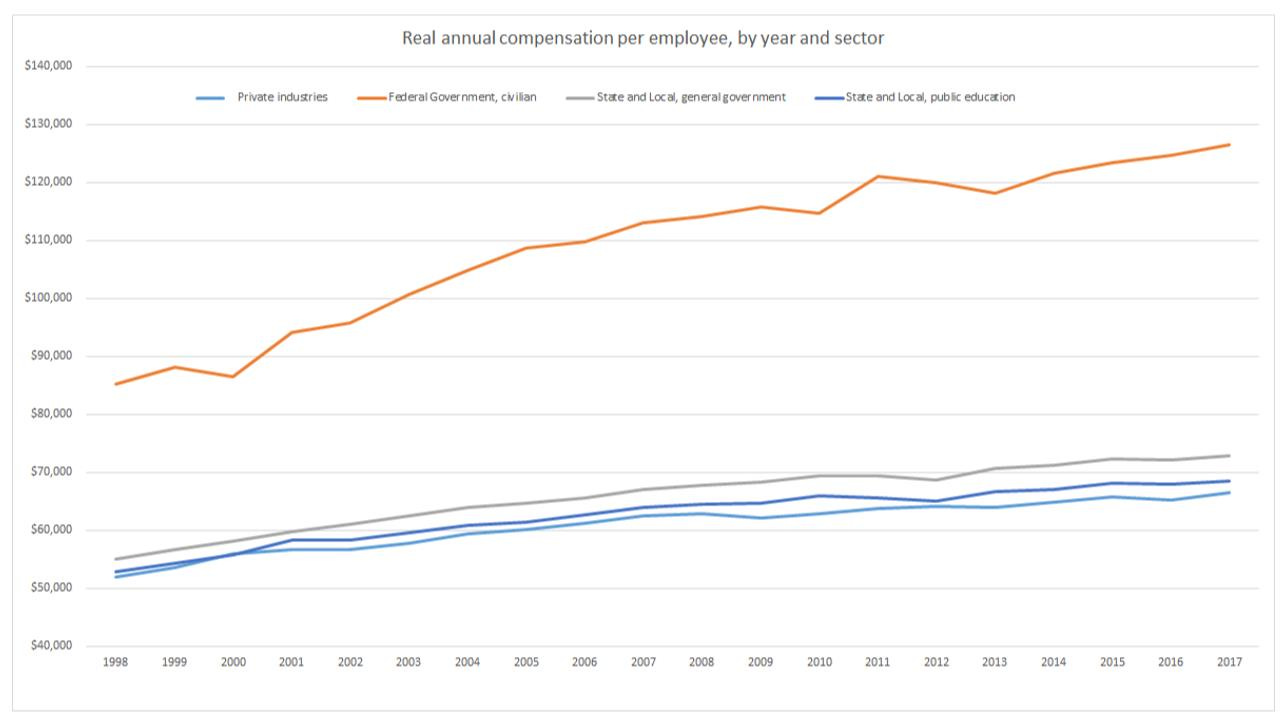

Total compensation from 1998 to 2017 grew somewhat more quickly in state and local government and public education than in the private sector, while growth of federal employee compensation far outpaced the other sectors.

Enrollment in the federal loan forgiveness plans has surged nearly 40%, to include at least 1.3 million Americans and has discouraged universities from controlling tuition costs.

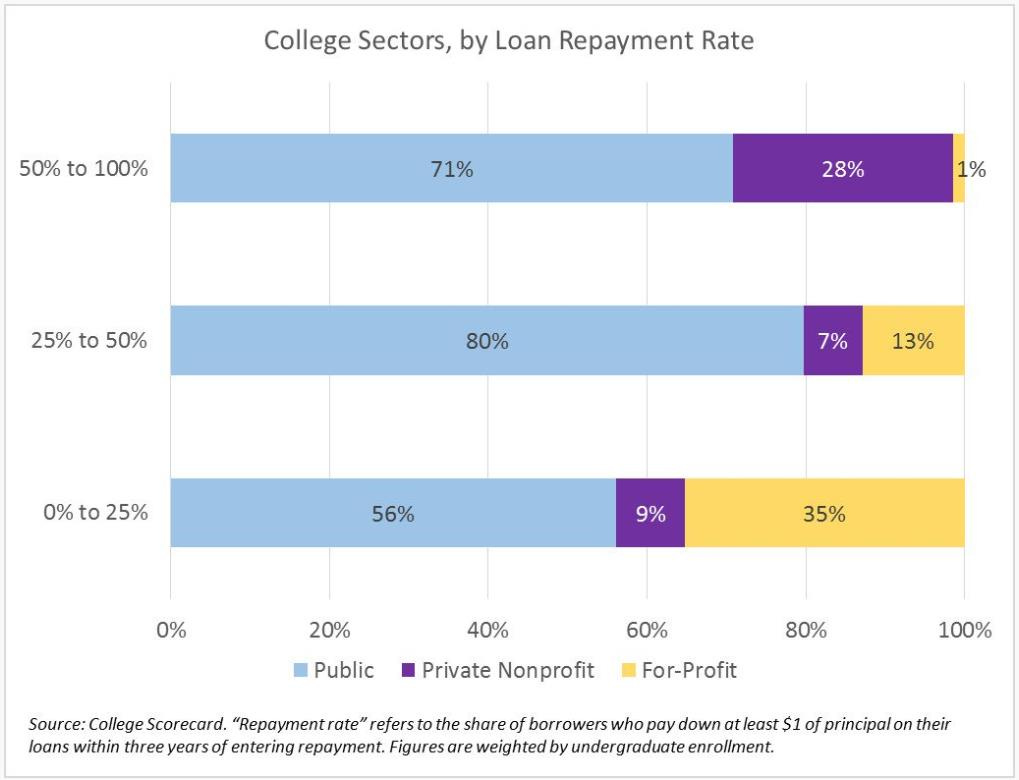

Most students who attend colleges with low repayment rates go to public schools. Add in private nonprofits, and nearly two-thirds of students at schools with very low repayment rates do not attend for-profit colleges. The figure is even higher, about 87 percent, for schools with repayment rates between 25 and 50 percent.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how the ideological uniformity of much of higher education ends up teaching students not how to think, but how to “groupthink.”

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12