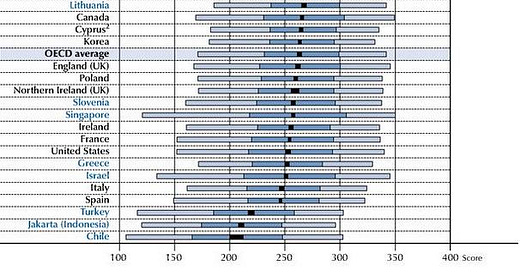

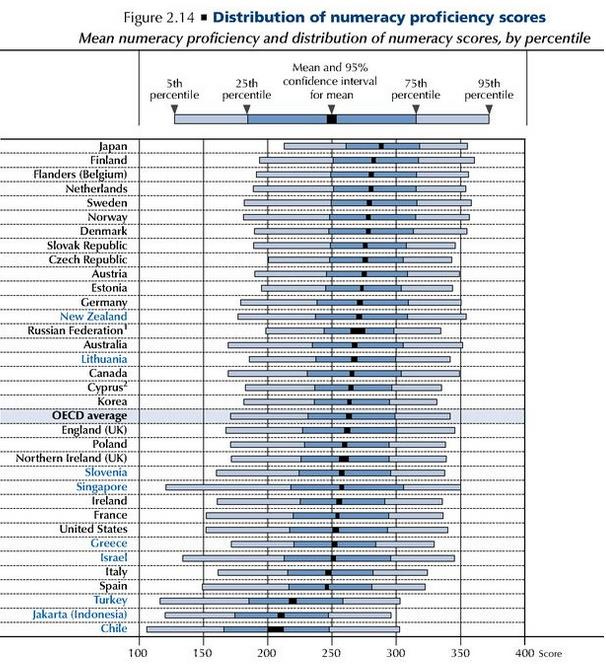

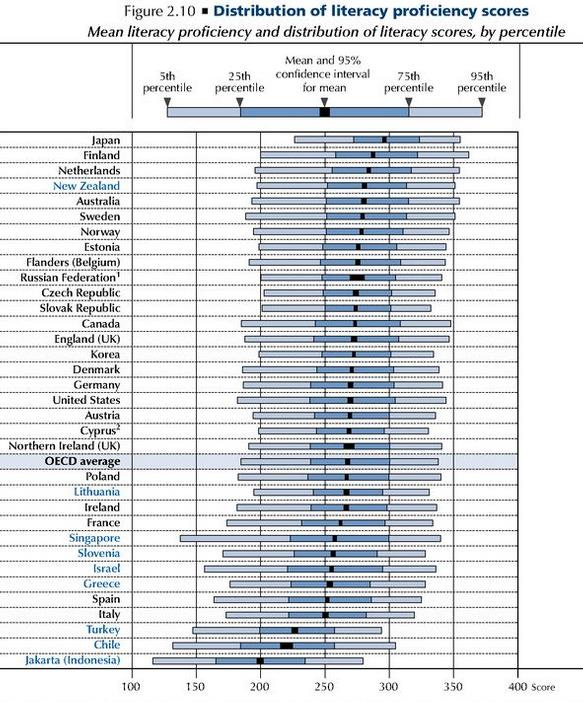

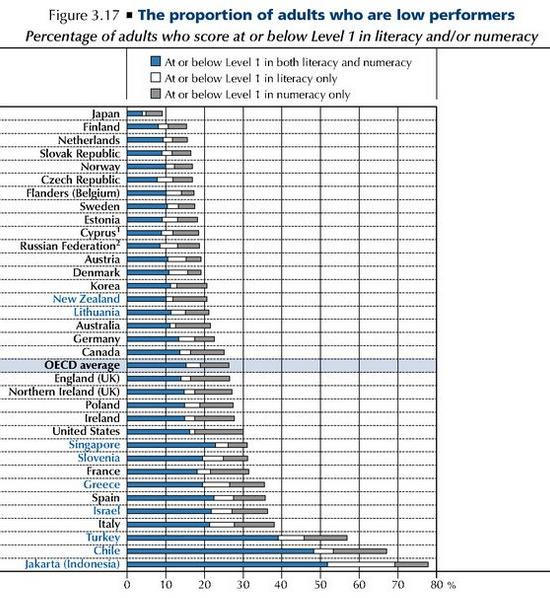

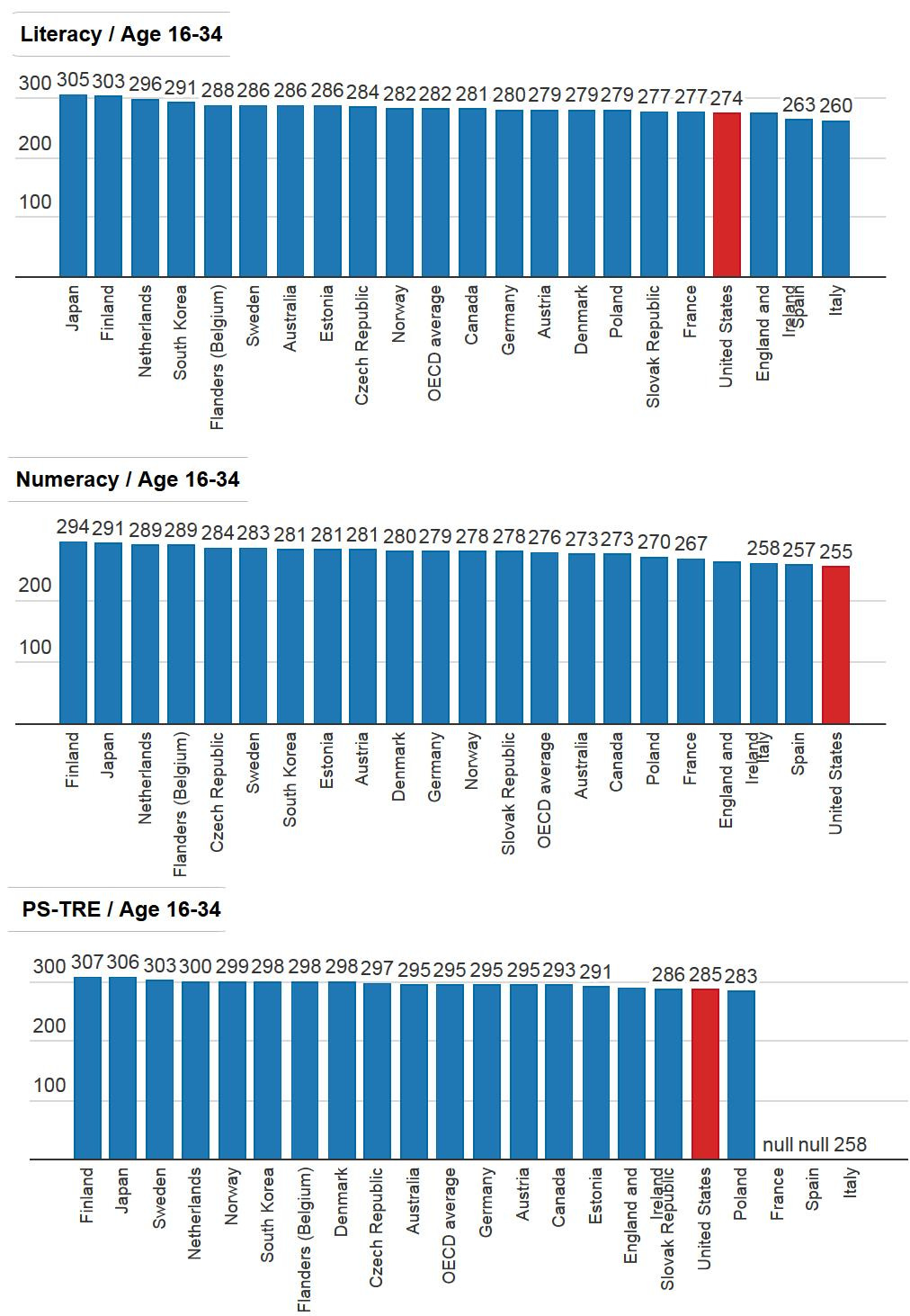

As Edward Conard has pointed out, based on data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Twenty-five percent of Americans score in the top-third globally on comparable tests of academic skills [,] while forty-five percent score in the bottom third -- meaning America has roughly one high-scorer for every two low-scorers. A third of Germans score in each the top, middle, and bottom third, leaving Germany with one high-scorer for every low-scorer -- twice as many high-scorers per low-scorer as America. Scandinavia has three times as many; Japan, nearly five times. A shortage of high-skilled labor leaves America’s unskilled workers less supervised relative to those in other high-wage economies, especially when innovation gives America’s high-skilled workers better opportunities than their counterparts in other high-wage economies.”

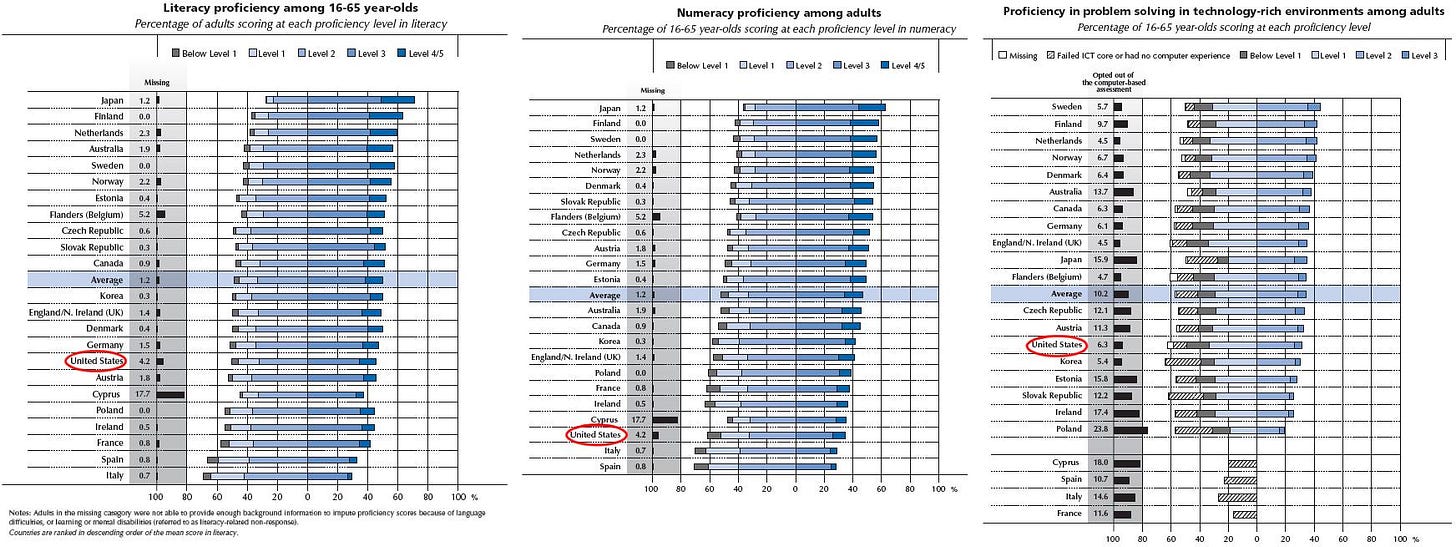

A first-ever comparison of adults in the United States and those in other democracies found that Americans were well below average in literacy, numeracy, and proficiency in problem-solving.

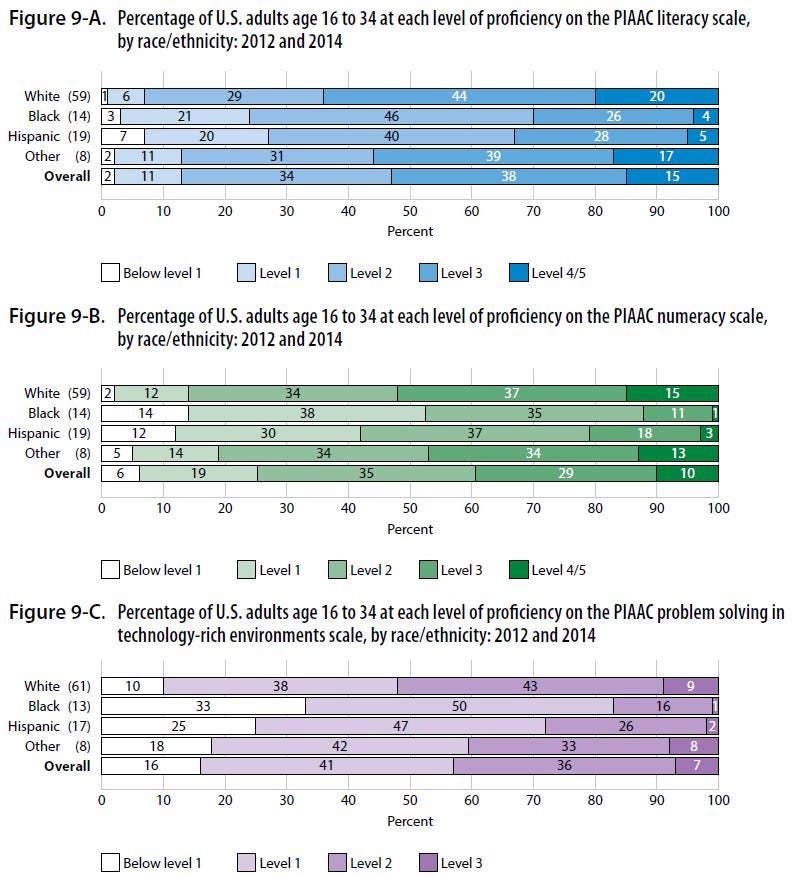

There is also a large racial gap in adult test scores in the U.S.

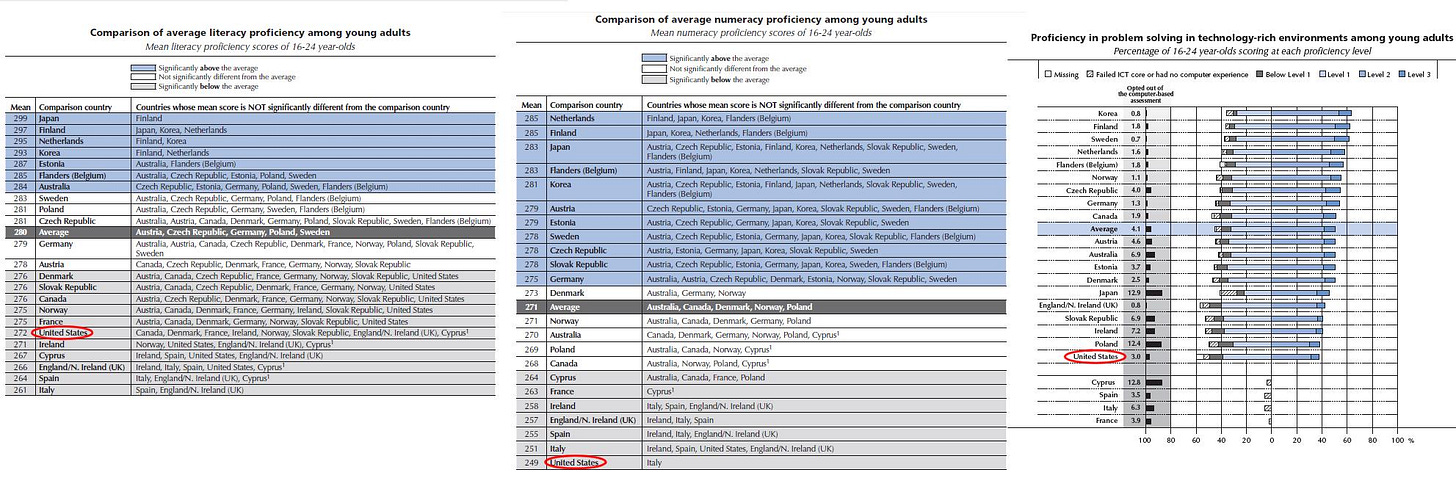

Young adults in the United States performed particularly poorly in the same comparison.

Researchers who parsed the same data concluded, “The comparatively low skill level of U.S. millennials is likely to test our international competitiveness over the coming decades. If our future rests in part on the skills of this cohort -- as these individuals represent the workforce, parents, educators, and our political bedrock -- then that future looks bleak.” The report says that the results were even more surprising because millennials “have attained the most years of schooling of any cohort in American history.”

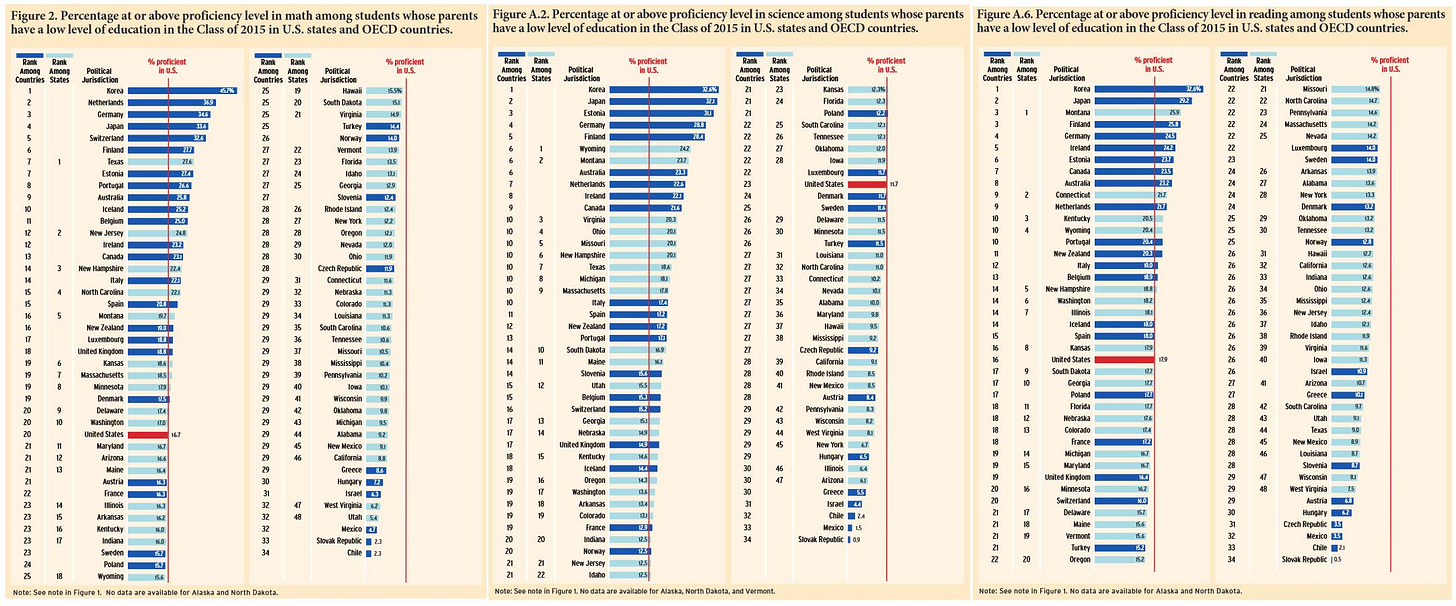

Poor U.S. student performance compared to student performance in other countries cannot be blamed on the relatively poor family backgrounds of U.S. students. As explained by researchers:

Not everyone agrees that the nation’s schools are in trouble. In their apology for the American school, David Berliner and Gene Glass seek to reassure Americans by trying to isolate the problem to minority groups or those of low income. ‘In the United States, if we looked only at the students who attend schools where child poverty rates are under 10 percent, we would rank as the number one country in the world,’ they write. But, this claim is highly misleading. The important question to ask is: Do students of the same family background do better in the United States than in other countries? … Our results reveal that the nation’s “educational shortcomings” are not just the problems of the other person’s child. When viewed from a global perspective, U.S. schools seem to do as badly at teaching those from better- educated families as they do at teaching those from less-well-educated families. Overall, the U.S. proficiency rate in math (35%) places the country at the 27th rank among the 34 OECD countries. That ranking is somewhat lower for students from advantaged backgrounds (28th) than for those from disadvantaged ones (20th). Countries with higher proficiency rates among students from better-educated families than the United States (43%) include Korea (73%), Poland (71%), Japan (68%), Switzerland (65%), and Germany (64%). Other major countries that score much higher than the United States include Canada (57%), France (55%), and Australia (55%).

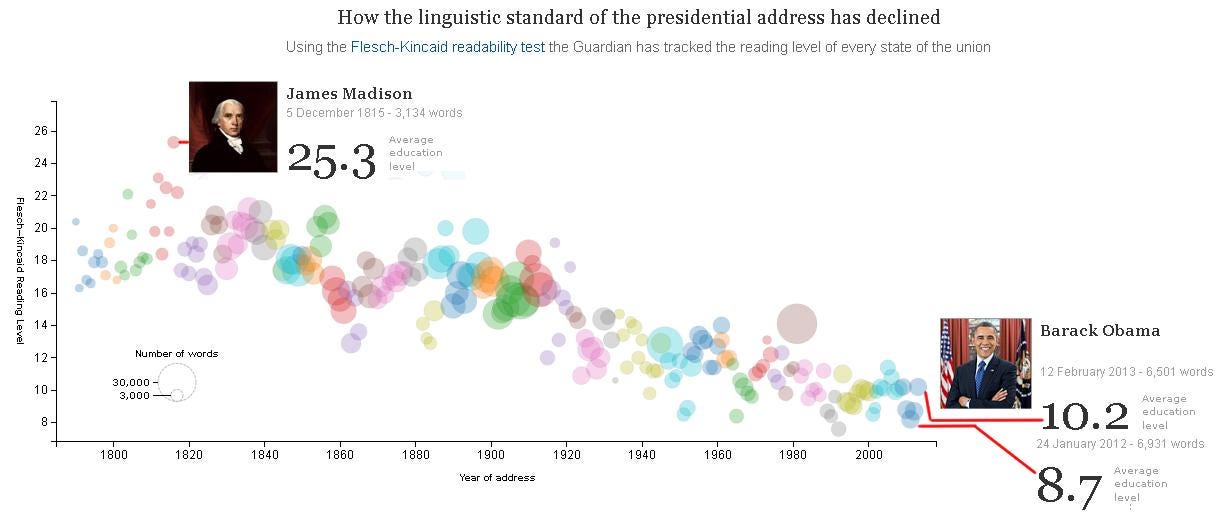

With all that said, it’s perhaps no surprise that the caliber of political discourse in the United States has also fallen over time. For example, the widely used Flesch-Kincaid readability test (which measures the U.S. grade level at which texts are written) shows that the grade reading level of the President’s State of the Union Address has plummeted steadily over the years.

For comparison, Lawrence Reed has described American colonial and post-colonial literacy rates as follows:

In 1983, Robert A. Peterson’s "Education in Colonial America" revealed some stunning facts and figures. “The Federalist Papers, which are seldom read or understood today even in our universities,” explains Peterson, “were written for and read by the common man. Literacy rates were as high or higher than they are today.” Incredibly, “A study conducted in 1800 by DuPont de Nemours revealed that only four in a thousand Americans were unable to read and write legibly” [emphasis mine] …

Estimates of the literacy rate among slaves on the eve of the Civil War range from 10 to 20 percent. By 1880, nearly 40 percent of southern blacks were literate. In 1910, half a century before the federal government involved itself in K-12 funding, black literacy exceeded 70 percent and was comparable to that of whites.

Daniel Lattier explained in a 2016 article titled "Did Public Schools Really Improve American Literacy?" that a government school system is no guarantee that young people will actually learn to read and write well. He cites the shocking findings of a study conducted by the US Department of Education: “32 million of American adults are illiterate, 21 percent read below a 5th grade level, and 19 percent of high school graduates are functionally illiterate, which means they can’t read well enough to manage daily living and perform tasks required by many jobs.” …

If you’re looking for a good history of how America traveled the path of literacy to a national education crisis, you can find it in a recent, well-documented book by Justin Spears and associates, titled Failure: The History and Results of America’s School System. The way in which government short-changes parents, teachers, and students is heart-breaking.

I promised to share a passage from Stephen Mansfield’s book [Lincoln’s Battle With God: A President’s Struggle With Faith and What It Meant for America], so now I am pleased to deliver it. Read it carefully, and let it soak in:

We should remember that the early English settlers in the New World left England accompanied by fears that they would pursue their “errand into the wilderness” and become barbarians in the process. Loved ones at home wondered how a people could cross an ocean and live in the wild without losing the literacy, the learning, and the faith that defined them. The early colonists came determined to defy these fears. They brought books, printing presses, and teachers with them and made the founding of schools a priority. Puritans founded Boston in 1630 and established Harvard College within six years. After ten years they had already printed the first book in the colonies, the Bay Psalm Book. Many more would follow. The American colonists were so devoted to education—inspired as they were by their Protestant insistence upon biblical literacy and by their hope of converting and educating the natives—that they created a near-miraculous culture of learning.

This was achieved through an educational free market. Colonial society offered “Dame schools,” Latin grammar schools, tutors for hire, what would today be called “home schools,” church schools, schools for the poor, and colleges for the gifted and well-to-do. Enveloping these institutions of learning was a wider culture that prized knowledge as an aid to godliness. Books were cherished and well-read. A respected minister might have thousands of them. Sermons were long and learned. Newspapers were devoured, and elevated discussion of ideas filled taverns and parlors. Citizens formed gatherings for the “improvement of the mind”—debate societies and reading clubs and even sewing circles at which the latest books from England were read.

The intellectual achievements of colonial America were astonishing. Lawrence Cremin, dean of American education historians, estimated the literacy rate of the period at between 80 and 90 percent. Benjamin Franklin taught himself five languages and was not thought exceptional. Jefferson taught himself half a dozen, including Arabic. George Washington was unceasingly embarrassed by his lack of formal education, and yet readers of his journals today marvel at his intellect and wonder why he ever felt insecure. It was nothing for a man—or in some cases a woman—to learn algebra, geometry, navigation, science, logic, grammar, and history entirely through self-education. A seminarian was usually required to know Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French and German just to begin his studies, instruction which might take place in a log classroom and on a dirt floor.

This culture of learning spilled over onto the American frontier. Though pioneers routinely moved beyond the reach of even basic education, as soon as the first buildings of a town were erected, so too, were voluntary societies to foster intellectual life. Aside from schools for the young, there were debate societies, discussion groups, lyceums, lecture associations, political clubs, and always, Bible societies. The level of learning these groups encouraged was astounding. The language of Shakespeare and classical literature—at the least Virgil, Plutarch, Cicero, and Homer—so permeated the letters and journals of frontier Americans that modern readers have difficulty understanding that generation’s literary metaphors. This meant that even a rustic Western settlement could serve as a kind of informal frontier university for the aspiring. It is precisely this legacy and passion for learning that shaped young Abraham Lincoln during his six years in New Salem.

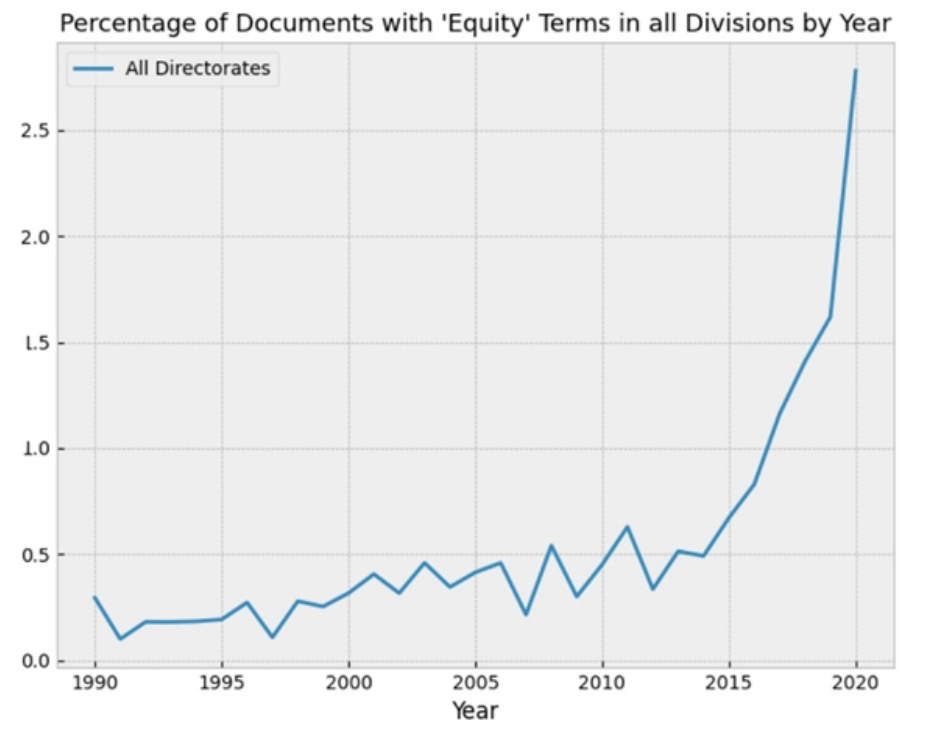

Researchers have found that grants for funding through the National Science Foundation have become more repetitive in their abstracts as they become increasingly filled with the jargon of “woke” language in the last several years. As the researchers report:

This report uses natural language processing to analyze the abstracts of successful grants from 1990 to 2020 in the seven fields of Biological Sciences, Computer & Information Science & Engineering, Education & Human Resources, Engineering, Geosciences, Mathematical & Physical Sciences, and Social, Behavioral & Economic Sciences. The frequency of documents containing highly politicized terms has been increasing consistently over the last three decades. As of 2020, 30.4% of all grants had one of the following politicized terms: “equity,” “diversity,” “inclusion,” “gender,” “marginalize,” “underrepresented,” or “disparity.” This is up from 2.9% in 1990. The most politicized field is Education & Human Resources (53.8% in 2020, up from 4.3% in 1990). The least are Mathematical & Physical Sciences (22.6%, up from 0.9%) and Computer & Information Science & Engineering (24.9%, up from 1.5%), although even they are significantly more politicized than any field was in 1990. At the same time, abstracts in most directorates have been becoming more similar to each other over time. This arguably shows that there is less diversity in the kinds of ideas that are getting funded. This effect is particularly strong in the last few years, but the trend is clear over the last three decades when a technique based on word similarity, rather than the matching of exact terms, is used.

This concludes this series of essays on trends in American higher education.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12