Trends in Higher Education – Part 8

Ideological insulation in college leads to ideological isolation after graduation.

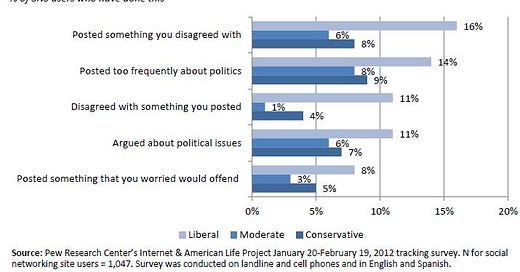

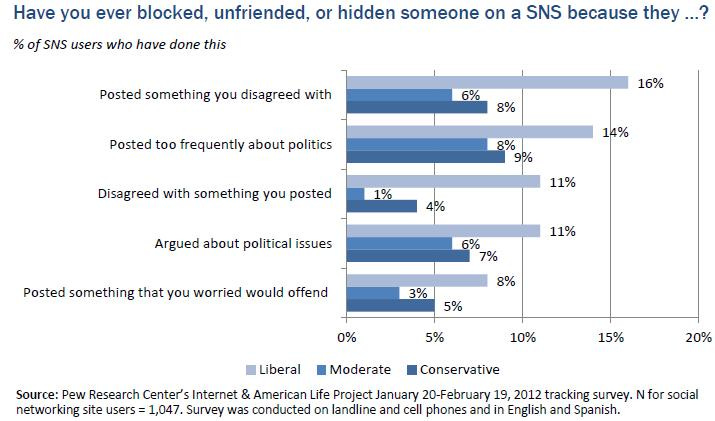

Perhaps because college graduates are less comfortable with opposing ideas to which they have had little exposure at their university, self-described liberals using social networking sites, as far back as 2012, were found to block, unfriend, or hide those with opposing views more often than others do.

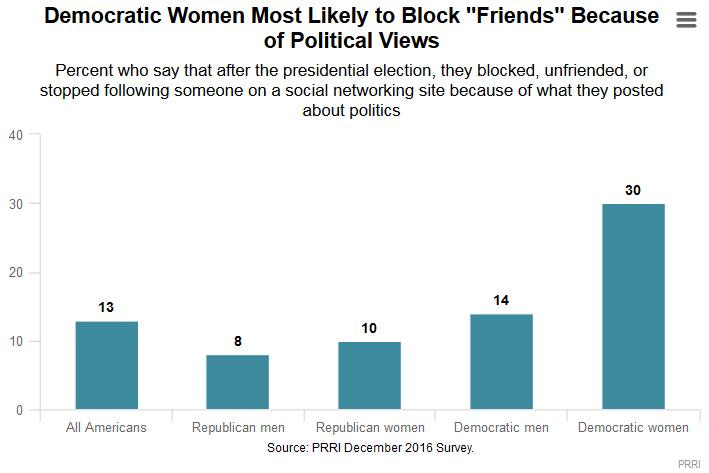

A PRRI survey showed that nearly one-quarter (24%) of Democrats say they blocked, unfriended, or stopped following someone on social media after the election because of their political posts on social media. Fewer than one in ten Republicans (9%) and independents (9%) report eliminating people from their social media circle. Political liberals are also far more likely than conservatives to say they removed someone from their social media circle due to what they shared online (28% vs. 8%, respectively).

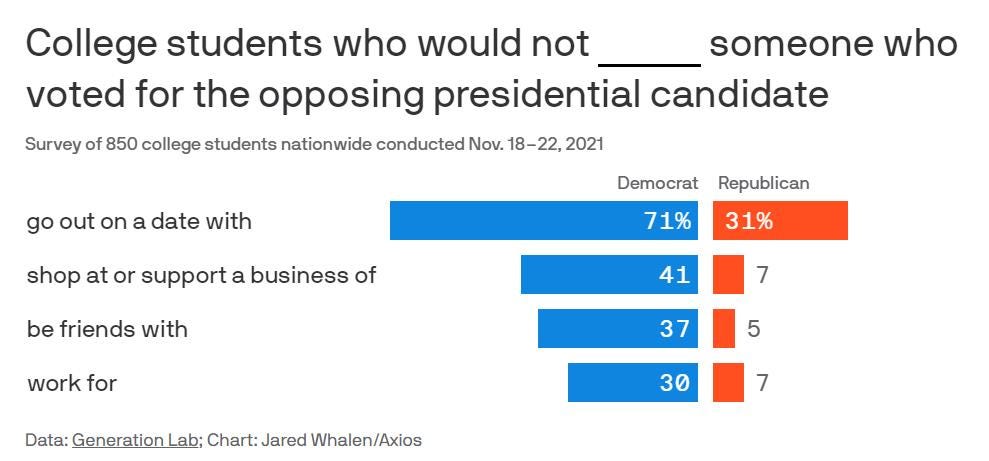

In 2021, nearly a quarter of college students wouldn’t be friends with someone who voted for the other presidential candidate — with Democrats far more likely to dismiss people than Republicans — according to Generation Lab/Axios polling: 5% of Republicans said they wouldn't be friends with someone from the opposite party, compared to 37% of Democrats; 71% of Democrats wouldn't go on a date with someone with opposing views, versus 31% of Republicans; 30% of Democrats — and 7% of Republicans — wouldn't work for someone who voted differently from them.

A June, 2021 study found that 15% of adults have ended a friendship over politics and that Republicans tend to have more bipartisan friendships than Democrats do: Just over half, 53% of Republicans said they have at least some friends who are Democrats, the study found, while about a third of Democrats (32%) said they have at least some Republican friends.

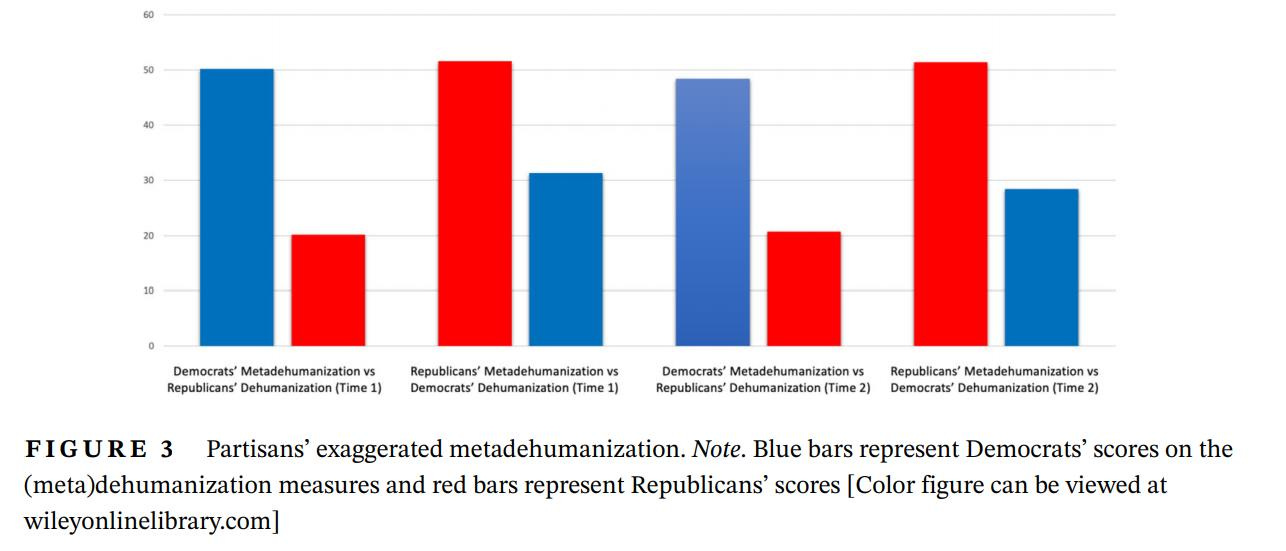

Greater exposure to opposing views also seems to improve people’s ability to understand those opposing views. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and his colleagues have shown that conservatives are better at understanding liberal views than vice versa. Researchers have also found that while members of both political parties believe members of the other political party dehumanize them, Democrats have a more exaggerated perception of Republicans’ dehumanizing them than Republicans have of Democrats dehumanizing them. Researchers found that:

The present research directly replicates past work suggesting that meta-dehumanization, the perception that another group dehumanizes your own group, erodes Americans’ support for democratic norms … We found the most politically engaged partisans held the most exaggerated, and therefore most inaccurate, levels of meta-dehumanization. Moreover, despite the socially progressive and egalitarian outlook traditionally associated with liberalism, the most liberal Democrats actually expressed the greatest dehumanization of Republicans. This suggests that political ideology can at times be as much an expression of social identity as a reflection of deliberative policy considerations, and demonstrates the need to develop more constructive outlets for social identity maintenance … [W]e hypothesized that partisans expected the other side would dehumanize them more than they actually did (H1). Therefore, we conducted a series of independent samples t-tests3 that compared each side’s meta-dehumanization with the other side’s dehumanization, both before and after the election results were finalized. Indeed, in direct replication of Moore-Berg et al. (2020a), Democrats perceived Republicans to dehumanize them more than they actually did (Time 1: Mdiff = 30.04, t(859) = 12.08, p < .001, d = 0.87; Time 2: Mdiff = 27.71, t(858) = 11.27, p < .001, d = 0.81), and Republicans perceived Democrats to dehumanize them more than they actually did.

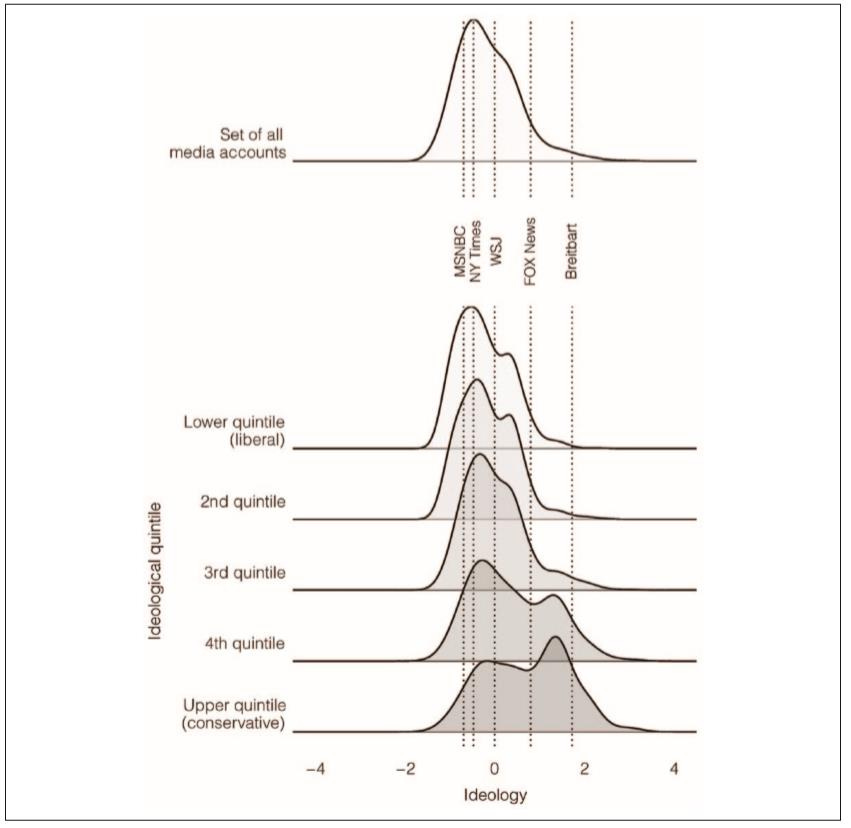

Researchers at Princeton and New York University studied the extent to which liberals and conservatives encounter counter-attitudinal messages and stated “we find asymmetries in individuals’ willingness to venture into cross-cutting spaces, with conservatives more likely to follow media and political accounts classified as left-leaning than the reverse.”

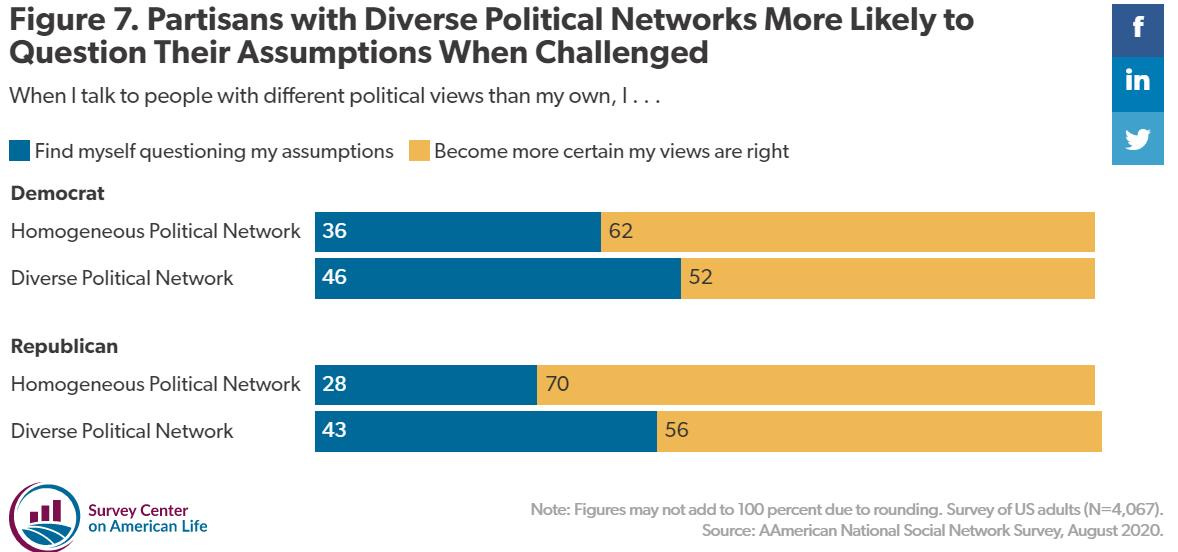

People living in small ideological bubbles are less likely to question their assumptions. In 2020, the American National Social Network Survey found that:

social network diversity plays a much more important role in how people respond to politically dissonant information (Figure 7). Nearly half (46 percent) of people with politically diverse networks, including 43 percent of Republicans and 46 percent of Democrats, say they question their assumptions when talking to people with different political views. In contrast, only 34 percent of Americans with politically homogeneous networks—and 28 percent of Republicans and 36 percent of Democrats with homogeneous networks—say they are likely to rethink their position when discussing politics with people who have different opinions.

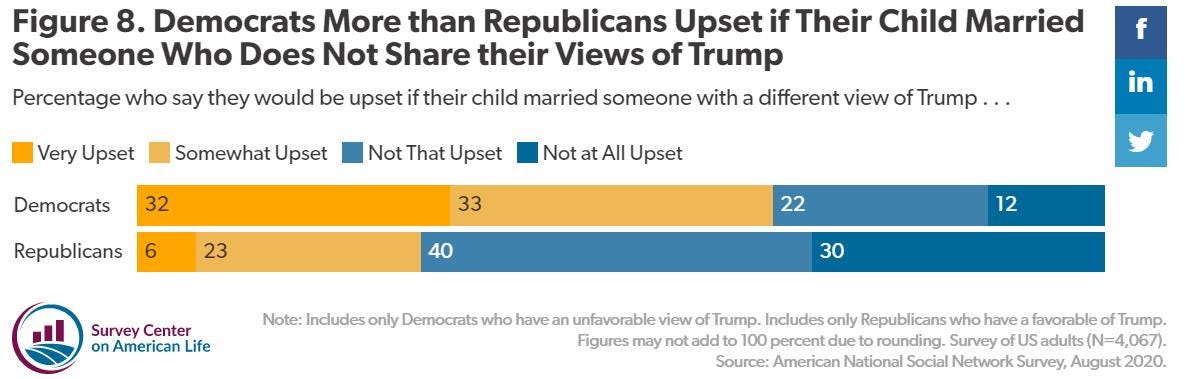

The same survey found that “Concerns about having someone join the family with an opposing view of Trump is a much greater concern for Democrats than Republicans (Figure 8). More than two-thirds (69 percent) of Democrats who view Trump unfavorably say they would be at least somewhat upset if their son or daughter married a Trump supporter. In contrast, only 30 percent of Republicans with a favorable view of Trump report that they would be upset if their child married someone who disliked Trump.”

The survey also found that higher education is associated with a 19 percentage point drop in the share of Republicans who have homogeneous networks (64% of Republicans without college education have politically homogeneous networks, as compared to 45% of Republican college graduates). Most college-educated Republicans have at least one person in their core network who supports the other party, whereas most college-educated Democrats (54%) have completely homogenous networks. Indeed, education seems to have no effect on increasing political diversity among Democrats’ core networks. As pointed out by Musa al-Gharbi, “The political skew of institutions of higher learning probably plays a significant role in these disparities. At college, students from conservative political backgrounds are consistently forced to confront views that run contrary to their own, and are surrounded by – and form relationships with — many more people who hold different perspectives from themselves. For Democrat-leaning students, this is much less the case.”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how technology perpetuates ideological isolation.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12