Eric Kauffman at the Center of Partisanship and Ideology issued a report in February 2021, that found the following:

My new report for the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology [is] [b]ased on eight comprehensive surveys of academic and graduate-student opinion across the U.S., Canada and Britain, [and] it buttresses the findings of numerous studies to provide hard data on the absence of viewpoint diversity and presence of discrimination against conservative and gender-critical scholars. High-profile activist excesses are mere symptoms of a much wider problem of progressive authoritarianism. Roughly 1 in 3 conservative academics and graduate students has been disciplined or threatened with disciplinary action. A progressive monoculture empowers radical activist staff and students to violate the freedom of political minorities like conservatives or “gender-critical” feminists, who believe in the biological basis of womanhood—all in the name of emotional safety or social justice.

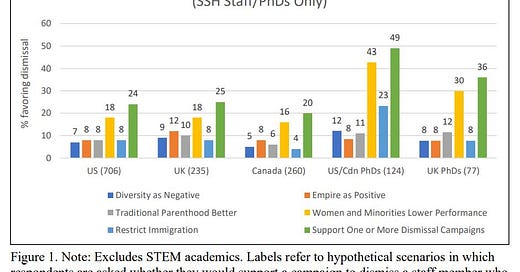

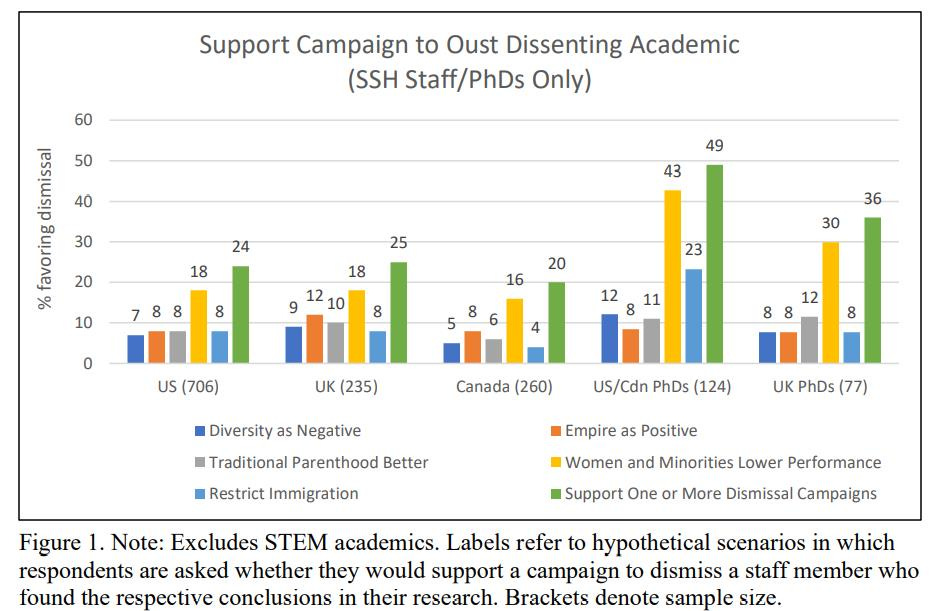

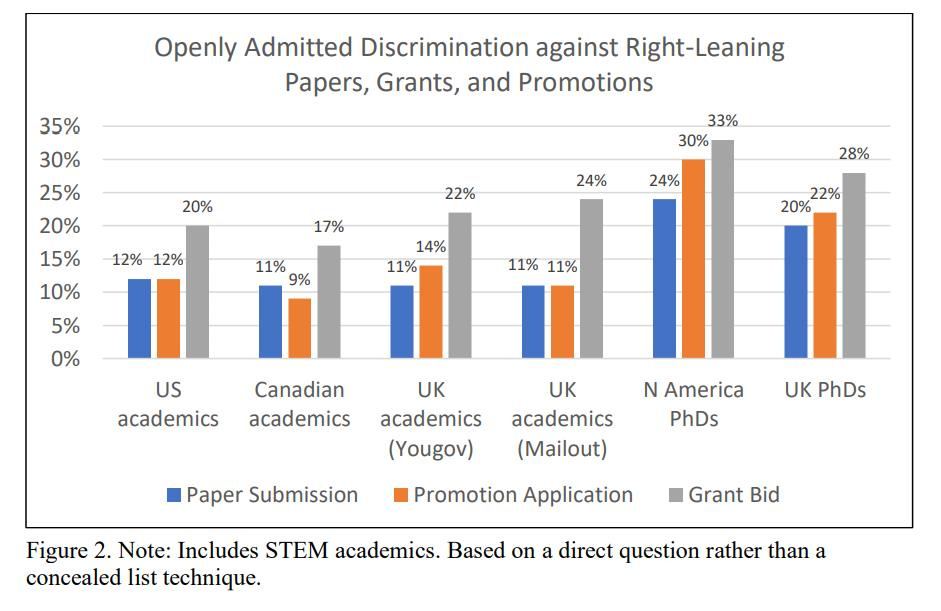

Political discrimination is pervasive: 4 in 10 American academics indicated in a survey this summer that they would not hire a known Trump supporter for a job. In Canada, the share is 45%, while in Britain, 1 in 3 academics wouldn’t hire a Brexit supporter. Between one-fifth and half of academics and graduate students are willing to discriminate against right-leaning grant applications, journal submissions and promotion cases. On a four-person panel, this virtually guarantees that a conservative will face discrimination.

Meanwhile, only 28% of American academics say they would be comfortable sitting with a gender-critical scholar over lunch, less even than the 41% who would sit with a Trump-voting colleague. Somehow this has become acceptable in a way it never would be for a person from a religious, as opposed to political, minority.

Some 75% of American and British conservative academics in social sciences and humanities say their departments offer a hostile climate for their beliefs. Nearly 4 in 10 American centrist faculty concur. This produces a chilling effect that results in self-censorship: I found that merely 9% of Trump-supporting academics say they would feel comfortable expressing their political beliefs to a colleague. Their progressive counterparts admit as much, with only 14% of all U.S. academics saying a Trump supporter would feel comfortable expressing his beliefs. In Britain, only 18% of Brexit-supporting academics would feel comfortable sharing their views, even though 52% of the British electorate supported Brexit.

Fully 7 in 10 conservative American academics say they self-censor in their teaching, research or academic discussions. Conservative scholars shy away from asking questions that go against the progressive consensus out of fear for their careers. This chilly climate is picked up by conservative and centrist students, which in turn influences the pipeline of who continues on to graduate school and the professoriate.

I find that conservative master’s students in social sciences and humanities fields are significantly more likely than other master’s students to believe their beliefs don’t fit in academia. Conservatives who think their politics wouldn’t fit are significantly less likely than others to be interested in pursuing an academic career. This isn’t about money. Conservative master’s students are no more likely than progressive students to say that pay is a factor discouraging them from going into academia. In effect, there is a feedback loop: Low viewpoint diversity reproduces the hostile climate that sustains the progressive monoculture that has developed in many faculties over the past four decades.

The result of this hostile environment is conformity to a culture that is out of alignment with the nation’s. As in previous studies, I find a low level of political diversity, with only 5% of American scholars in the social sciences and humanities identifying as conservative. In the U.S. and Canada, academics on the left outnumber those on the right by a ratio of 14 to 1.

In 2017 and 2018, several liberal academics conducted a study to determine if political bias was so pervasive in “grievance studies” disciplines that adaptations of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” and a paper explaining “rape culture” by monitoring dog-humping incidents at dog parks would be accepted by leading academic journals. They were.

This lack of viewpoint diversity in higher education, especially in the social sciences, yields biased research conclusions. (It also leads to flawed scientific methodologies and conclusions.)

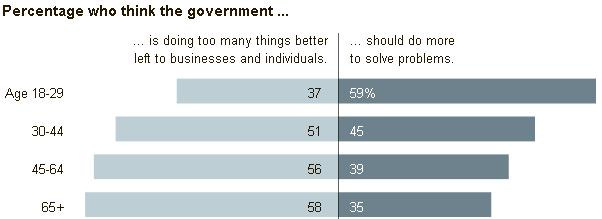

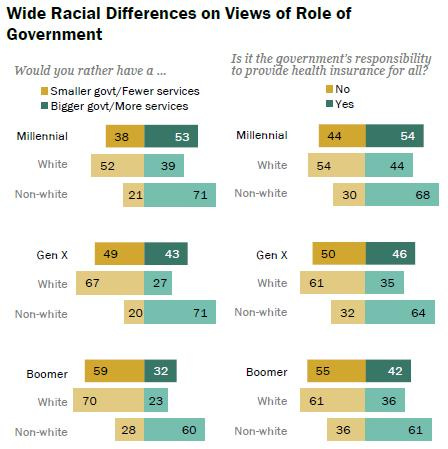

Younger people are also much more likely to think the government should do more to solve problems.

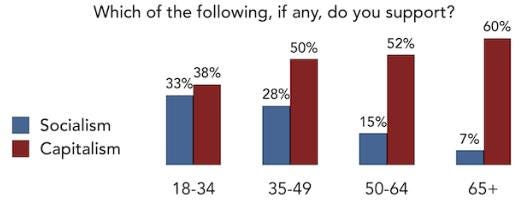

Young people, according to a 2016 Harvard University poll, are also the most likely to support socialism, not capitalism.

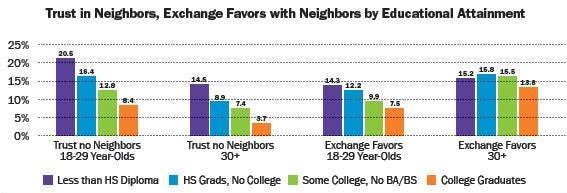

At the same time, those under 30 are least likely to trust their neighbors and exchange favors with them in their communities.

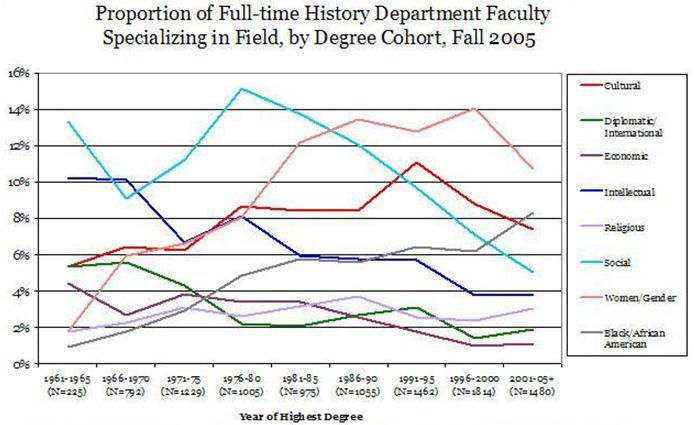

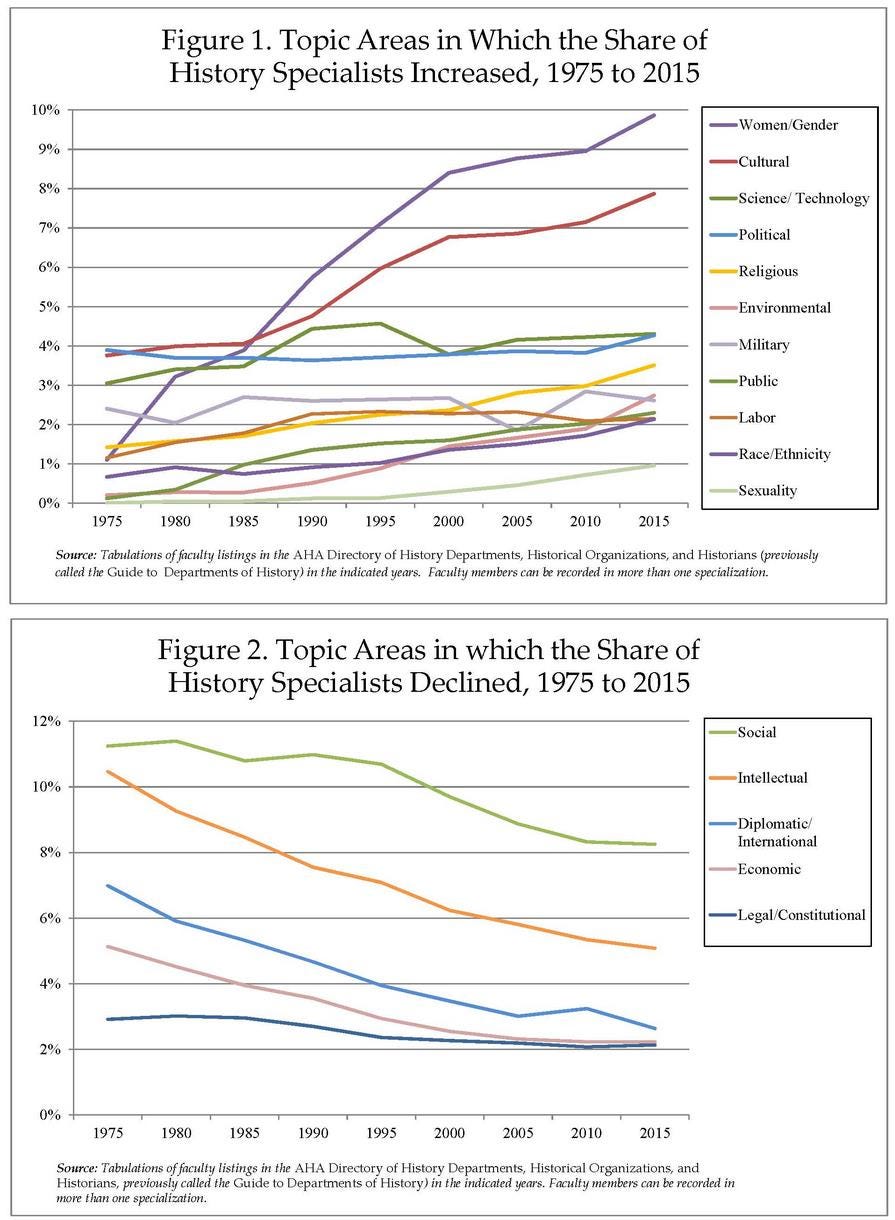

Surveys show that the study of history on college campuses has become dominated by the study of race and gender, to the exclusion of other subjects such as economic and intellectual history. A broad survey published by the American Historical Association, the association of all historians, shows that the proportion of full-time history department faculty specializing in women and black studies has risen significantly, while the proportion of faculty specializing in economic or intellectual history has decreased.

There has been a large increase in the number of historians who specialize in women and gender, and race and ethnicity, with other specialties declining.

A report released by The College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR) reveals that the average salary for full professors of “Area, Ethnic, Cultural, Gender, and Group Studies” during the 2017-2018 academic year was significantly more per year more than for Biology, Mathematics and Statistics, and Science professors. Professors of this type also make significantly more than traditional liberal arts professors.

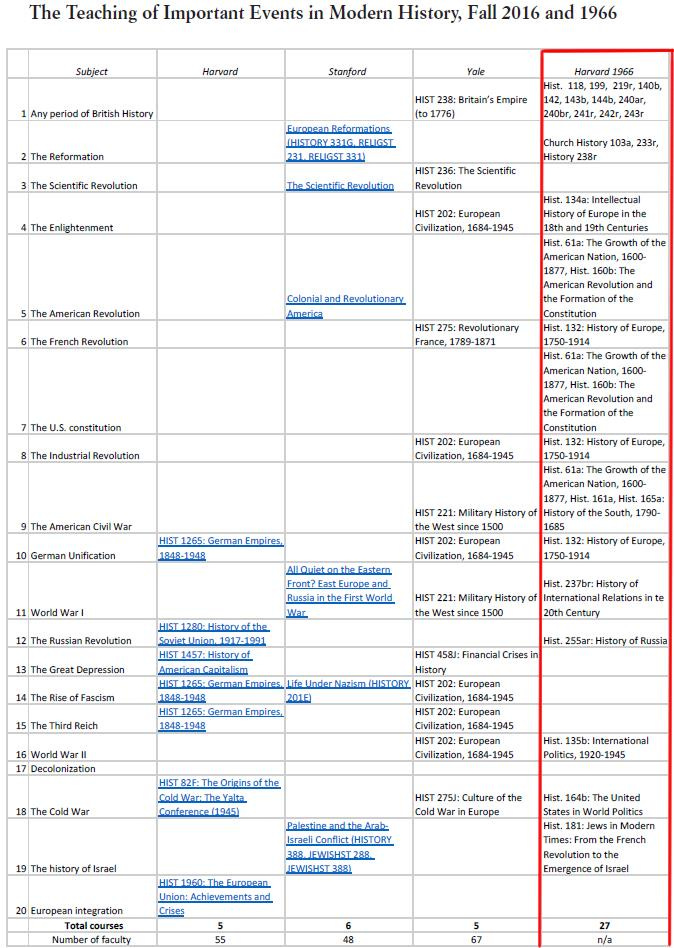

The following chart shows how few major historical events were taught in three Ivy League schools in the fall of 2016, compared to what was taught at Harvard in 1966.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how groupthink makes students scared to think.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

Terrifying in that it is such a pervasive sickness and that there is no easy path for curing it.