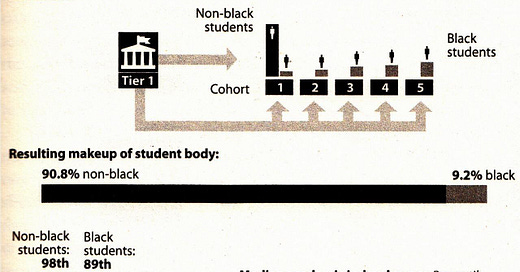

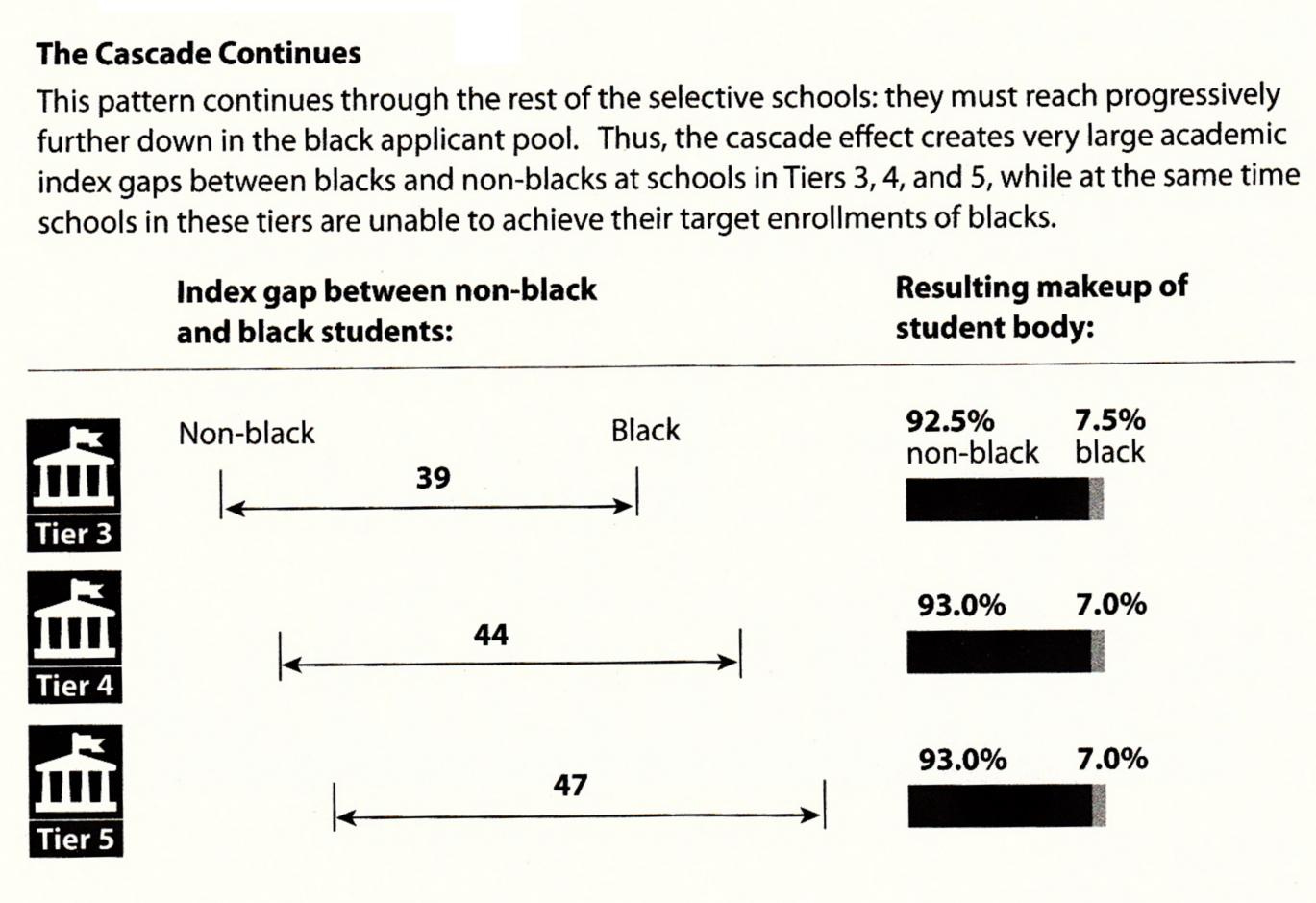

As was discussed in a previous essay, while there is little diversity of ideas at universities, admissions programs that give students preferences based on race alone have become entrenched. The charts below show how the racial sorting system has come to operate in higher education.

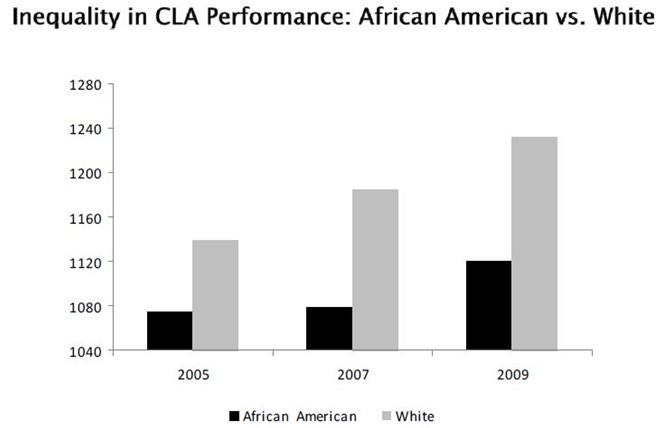

As a result, fewer black students admitted under racial preference programs are able to compete academically with many other admitted students, as evidenced by Collegiate Learning Assessment results.

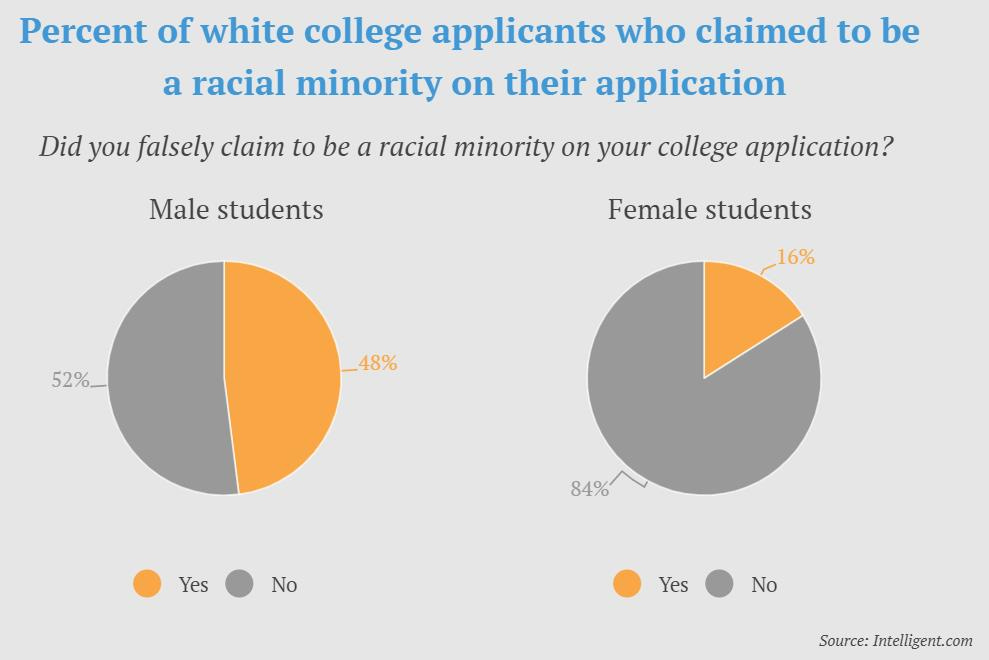

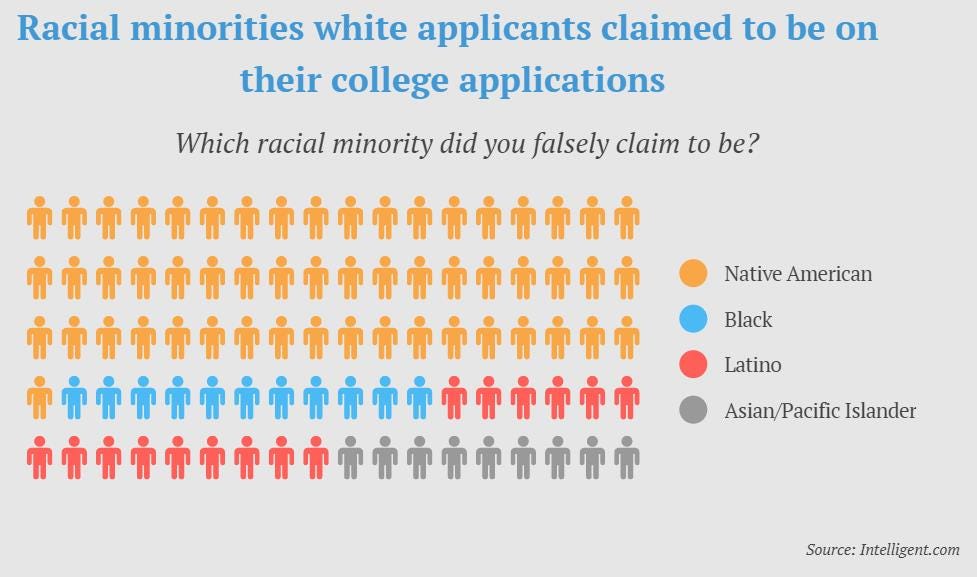

Race preferences have been so widely applied that many white students today are pretending to be minorities on their college applications to increase their chances of getting accepted into those colleges. Intelligent.com asked 1,250 white college applicants ages 16 and older if they lied on their application by indicating they were a racial minority. 34% of white Americans who applied to colleges or universities admit to lying about being a racial minority on their application. 48% of people who lied claimed to be Native American. 3/4 of people who faked being a racial minority on their applications were accepted by the colleges to which they lied.

(Ibram X. Kendi, whose “anti-racism” ideology falsely assumes all disparities among people grouped by race are caused by racism, initially tweeted the results of this study, but then deleted the tweet after realizing it contradicted his own assumption.)

Black graduation rates tend to be significantly lower than white graduation rates. As researchers at Duke and Cornell have concluded, “The evidence suggests that racial preferences are so aggressive that reshuffling some African American students to less-selective schools would improve some outcomes due to match effects dominating quality effects.” This result does a disservice to the very people racial preference programs are supposed to help.

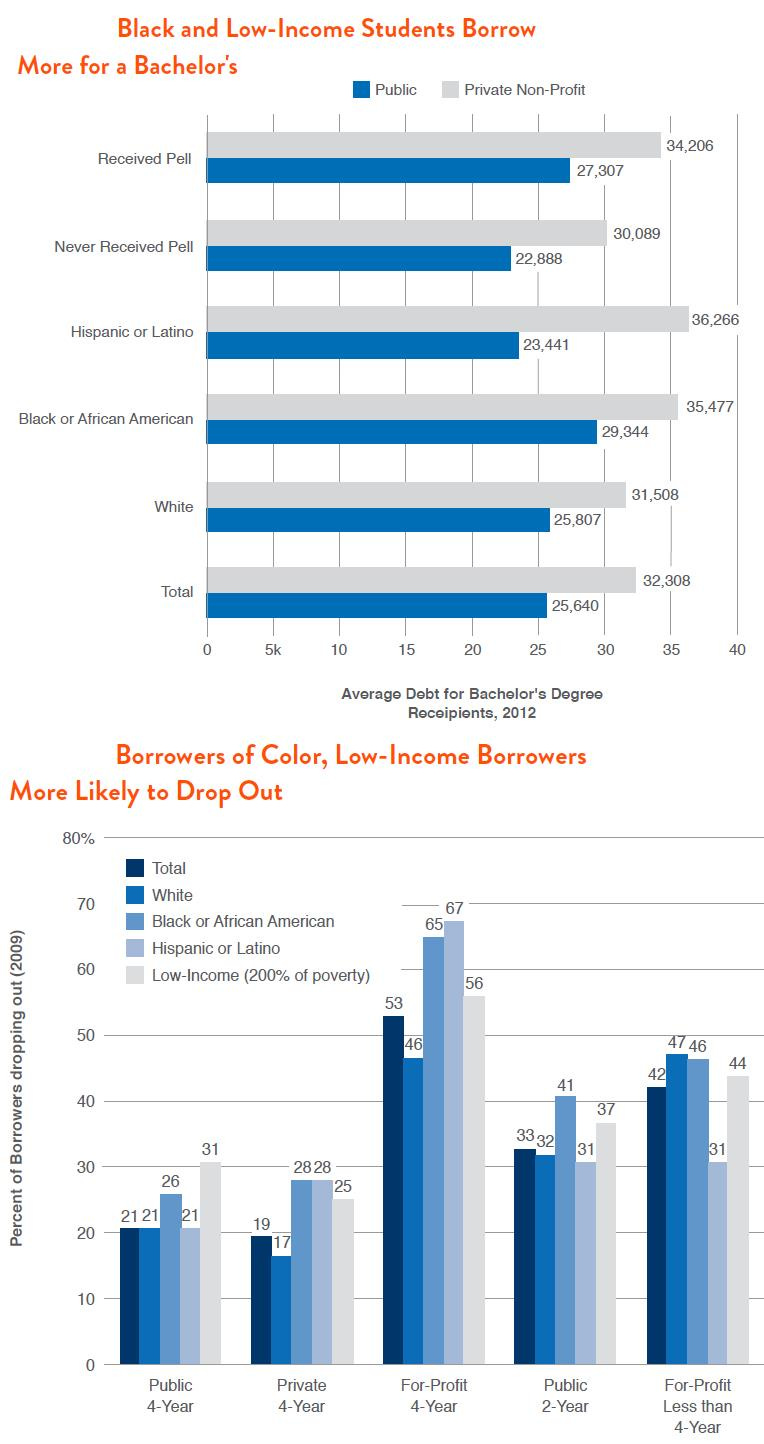

Black and low-income students borrow more for a bachelor’s degree than other groups, yet they also are more likely to drop out of college.

Still, as William Julius Wilson explains in his book The Declining Significance of Race:

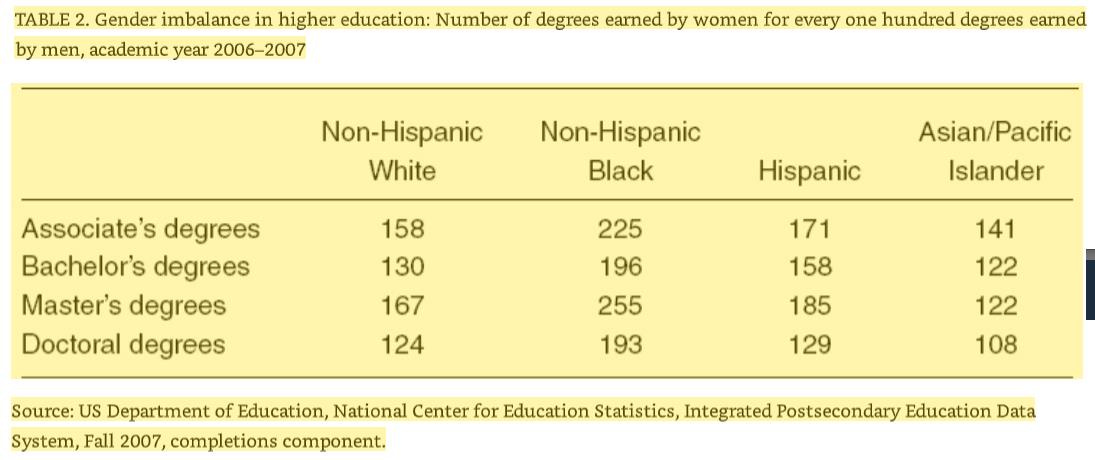

Black women have also far outpaced black men in college completion in recent years. Despite the fact that the gender gap in college degree attainment is increasing across all racial groups, with women generally exceeding men in rates of college completion, this discrepancy is particularly acute among African Americans. That gap has widened steadily over the past twenty-five years. In 1979, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees earned by black men, 144 were earned by black women. In 2006 to 2007, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees conferred on black men, 196 were conferred on black women—nearly a two-to-one ratio. To put this gap into a larger context, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees earned by white men and every 100 earned by Hispanic men, white women earned 130 and Hispanic women earned 158, respectively (see table 2). The gap widens higher up on the educational ladder. For every 100 master’s degrees and 100 doctorates earned by black men, black women earned 255 and 193, respectively. These ratios have huge implications for the social organization of the black community. A discussion of the black class structure today has to include a gender component to show the increasing proportion of black women and decreasing proportion of black men in higher socioeconomic positions.

Research has also shown that while black first- and second-generation immigrants make up just 13 percent of the U.S. black population, black first- and second-generation immigrants are significantly overrepresented demographically within elite academia, even though data suggest relatively few and generally modest differences in the social origins between black students of immigrant and native origins (including indicators such as income, wealth, parental employment, parental child-rearing practices, peer support, and academic preparation).

Researchers have also found that:

the educational attainment of second-generation Nigerian Americans exceeds other second-generation black Americans, third- and higher generation African Americans, third- and higher generation whites, second-generation whites, and second-generation Asian Americans. Controlling for age, education, and disability, the wages of second-generation Nigerian Americans have reached parity with those of third- and higher generation whites. The educational attainment of other second-generation black Americans exceeds that of third- and higher generation African Americans but has reached parity with that of third- and higher generation whites only among women. These results indicate significant socioeconomic variation within the African American/black category by gender, ethnicity, and generational status …

As John McWhorter has explained, “The [flawed] idea is that animus against black Americans—as opposed to Latinos or Asians—is so profound as to stanch striving. But that line is a tad elderly now, and the success since the 1970s of so many Caribbean and African immigrants—richly familiar with racism—has shown its obsolescence. In Ivy League institutions, typically almost half of black students come from immigrant families, despite such students representing less than 15 percent of the general black population of people their age.”

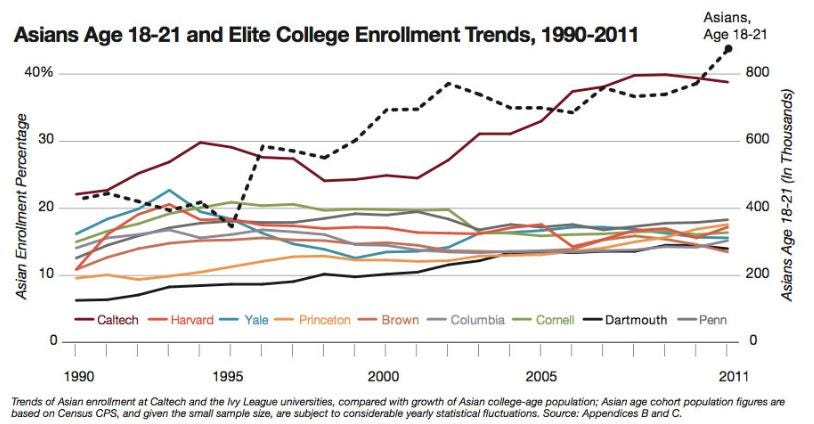

At the same time, under such programs, other, non-preferred minorities appear to face unfair enrollment caps at elite universities. The chart below shows that as the college-age Asian population has grown, Asian student admissions to elite universities (with the exception of Caltech) have been strictly limited. Updated figures can be found here.

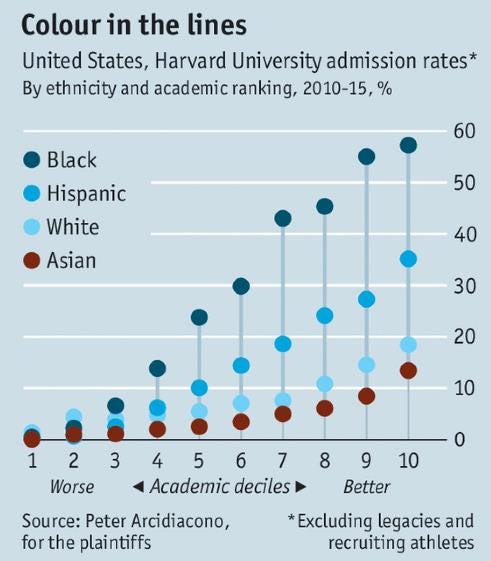

Data from a lawsuit brought by Asian-Americans against Harvard University show that blacks in the same academic decile have much higher admission rates than other racial groups in the same academic decile.

If the Harvard admissions were based solely on academic measures, the admitted class would be roughly 35% white, 1% black, 3% Hispanic, and 52% Asian.

Researchers in 2020 found that “Asian Americans would be admitted at a rate 19% higher absent this [discriminatory] penalty. Controlling for one of the primary channels through which Asian American applicants are discriminated against—the personal rating—cuts the Asian American penalty by less than half, still leaving a substantial penalty.”

The Department of Justice also found Yale University to be discriminating in admissions based on race, with black and Hispanic students having a much higher chance of being admitted than white with the same academic credentials.

A 2016 survey of college and university admissions directors found that 42 percent reported that “some colleges are holding Asian American applicants to higher standards” than all other students.

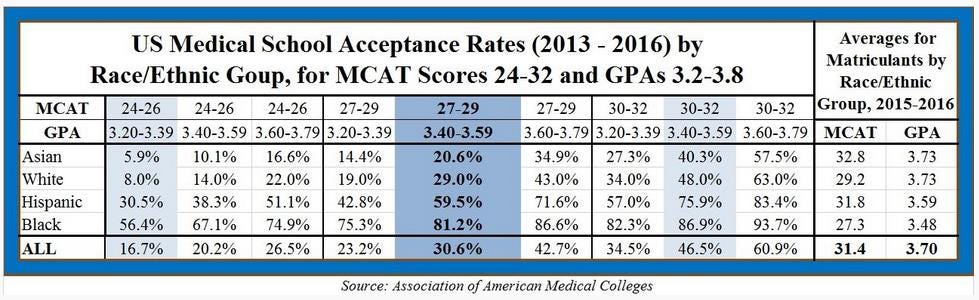

This dynamic is reflected in medical school acceptance rates, which show that among applicants with the same test scores and GPAs, blacks and Hispanics are much more likely to be admitted to medical school than their Asian and white peers with the same test scores and GPAs.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at ways of measuring the merits of higher education.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12