There’s evidence that the quality of teachers declined for a period after the 1960’s. Researchers have found that students through the early 2000’s were much less likely to find a teacher of the highest academic ability than was a student in 1964. Another study found that a predominant reason for that decline is that while increased unionization has driven teacher wages up overall by about 8 percent, it has also led to a phenomenon known as “wage compression” in which the gap in pay between the highest- and lowest-aptitude teachers is made much smaller, such that the biggest gains from unionization go to the lowest-aptitude teachers. In the 1960’s, there was a large gap in pay between teachers who went to highly selective schools and those who didn’t. But by 2000, “most states had earnings ratios near one for all aptitude groups” such that teachers get paid about the same regardless of where they went to college, making other professions (professions that more proportionately award aptitude) more attractive. And so the best potential teachers were avoiding teaching and doing something else instead.

Since then, the quality of new teacher applicants has been rising. The University of Washington’s Dan Goldhaber and Joe Walch find that “teacher applicants and new teachers in recent years have significantly higher SAT scores than their counterparts in the mid-1990s.” Still, researchers have also found that the cognitive skills of teachers correlate with student performance and that there is great international variation in teacher cognitive skills. The figure below arrays the median teacher numeracy and literacy skills across countries against the skills of adults in different educational groups within Canada, the country with the largest sample. This figure shows that U.S. teachers perform lower on numeracy and literacy skills measures compared to the median skills of general workers with bachelor degrees and master degrees.

The same researchers found that student performance correlates with teacher skills in the U.S. such that the generally lower teacher skills correlate with generally lower student performance.

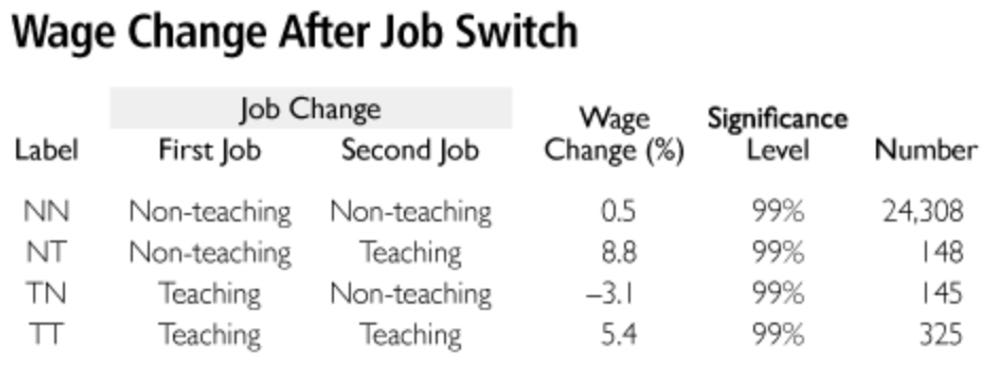

Data also shows that the (relatively few) teachers who leave teaching for a non-teaching job end up earning less than they did while teaching.

The first analysis of the effect of teacher collective bargaining on long-run labor market and educational attainment outcomes by researchers at Cornell suggests that teacher collective bargaining worsens the future labor market outcomes of students. The researchers found:

Our estimates suggest that teacher collective bargaining worsens the future labor market outcomes of students: living in a state that has a duty-to-bargain law for all 12 grade-school years reduces earnings by $800 (or 2%) per year and decreases hours worked by 0.50 hours per week. The earnings estimate indicates that teacher collective bargaining reduces earnings by $199.6 billion in the US annually. We also find evidence of lower employment rates, which is driven by lower labor force participation, as well as reductions in the skill levels of the occupations into which workers sort. The effects are driven by men and nonwhites, who experience larger relative declines in long-run outcomes.

The researchers reported that “We find strong evidence that teacher collective bargaining has a negative effect on students’ earnings as adults.” The study compares outcomes for students in states that mandate collective bargaining before and after the collective-bargaining requirement was imposed to outcomes for students over the same period in states that did not require collective bargaining. It also adjusted for the share of the student’s state birth cohort that is black, Hispanic, white and male. Students who spent all 12 years of their elementary and secondary education in schools with mandatory collective bargain earned $795 less per year as adults than their peers who weren’t in such schools. They also worked on average a half hour less per week, were 0.9% less likely to be employed, and were in occupations requiring lower skills. The authors found that these add up to a large overall loss of $196 billion per year for students educated in the 34 states with mandated collective bargaining.

The National Council on Teacher Quality found that education majors in college benefit from lenient grading standards and a lack of objectively-based assignments.

The National Council on Teacher Quality also concluded in 2013 that U.S. colleges of education are an “industry of mediocrity” that generally produce teachers ill-prepared to work in elementary and high-school classrooms. The Council assigned ratings of up to four stars to 1,200 programs at 608 institutions that collectively account for 72 percent of the graduates of all such programs in the nation and concluded that fewer than 10 percent of the programs earned three or more stars. Only four, all for future high-school teachers, received four stars. About 14 percent got zero stars.

Graduate Record Exam (GRE) scores among those intending to major in education are generally significantly lower than those of people intending to major in other subjects.

Average Verbal and Quantitative Reasoning GRE scores by intended graduate major are listed here.

As Frederick Hess points out, the licensing requirements that make future teachers enter educational programs may be doing the teaching profession a disservice:

Licensure systems require would-be educators to earn credentials through programs that typically consist of courses at education schools and student-teaching under the supervision of education-school faculty. These prerequisites narrow the pool of potential teachers, saddle educators with onerous costs, and deter career switchers and non-traditional candidates from pursuing teaching careers. The costs of this approach take the form of both money and time. Analyst Chad Aldeman, a former Obama administration official, has estimated that licensure requirements mean that it costs about $25,000 and requires 1,500 hours to train the average teacher — more hours than the typical teacher works each year. The requirements bar a host of seemingly qualified, promising candidates from applying for teaching positions and are especially burdensome for professionals seeking new careers. The results can be ludicrous. The conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra would not be eligible to teach band in a local junior-high school. CalTech's doctoral students would not be able to take part-time jobs teaching Advanced Placement calculus in a local high school.

Other researchers have found that if only the bottom 8 percent of teachers were replaced with average teachers, we could expect future gains of over $100 trillion to the gross domestic product. The largest study of a pay for performance program in the U.S. that included bigger rewards for good teaching and stiffer penalties for bad teaching compared to most other programs found that pay for performance rules significantly increased the voluntary attrition of low-performing teachers and improved the performance of the teachers retained.

The state of civics knowledge among Americans also mirrors the low interest in civics knowledge even among civics teachers. As summarized by Frederick Hess:

A 2018 survey by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that barely one in four Americans could name the three branches of government. A study by the Woodrow Wilson Foundation concluded that just one in three Americans could pass the nation’s citizenship test. And less than one-fourth of eighth-graders were judged proficient on the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress civics test.

Given the frayed state of our civil society and these dispiriting numbers, one might expect the nation’s civics educators to be up in arms. But a new survey published this week by the RAND Corporation suggests otherwise. The survey, a follow-up to a 2010 survey published by the American Enterprise Institute, asked 223 high school civics teachers in fall 2019 which aspects of the subject they deem essential to know and how confident they are that students are learning these things.

Civics teachers appear less convinced that most of what they teach actually matters. Particularly disconcerting, just 32 percent think it’s essential for their graduates to “know facts (e.g., the location of the 50 states) and dates (e.g., Pearl Harbor).” Knowledge about “periods such as the American Founding, the Civil War and the Cold War” fared little better, with 43 percent of teachers viewing such knowledge as essential—down sharply from 63 percent in 2010. At a time when historical revisionism is rampant, with discussion of key figures and developments frequently unmoored from the historical record, it’s bizarre to see those charged with preparing citizens doubting that knowledge is an important part of that preparation.

Indeed, not only are civics teachers mostly blasé about historical knowledge, but they’re also less concerned than one would expect with whether students understand how the American system works. Just 53 percent think it’s essential that students understand concepts like federalism, separation of powers and checks and balances (down from 64 percent in 2010), and just 43 percent believe it’s important that students understand economic principles such as “supply and demand and the role of market incentives.” Sixty-five percent say it’s essential that students are able to identify the protections guaranteed by the Bill of Rights (down markedly from 83 percent in 2010), while two-thirds feel that way about students embracing the responsibilities of citizenship, such as voting and jury duty. That’s right: Fully one-third of civics teachers are okay if their students graduate without knowing what’s in the Bill of Rights.

What did civics teachers deem especially vital? Well, only two out of 12 aspects of civics were judged more essential in 2019 than in 2010. One was that students “be tolerant of people and groups who are different from themselves” (deemed essential by 80 percent) and the other was that students “see themselves as global citizens living in an interconnected world” (66 percent). While laudable enough, both are notably untethered to knowledge or the distinctive American political tradition …

As for the protections in the Bill of Rights, the responsibilities of citizenship, and the constitutional mechanisms that undergird our freedoms, it’s simply bizarre that anyone would choose to be a civics teacher unless they thought these things were essential.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look trends in teacher pay, discipline, and discretion.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6