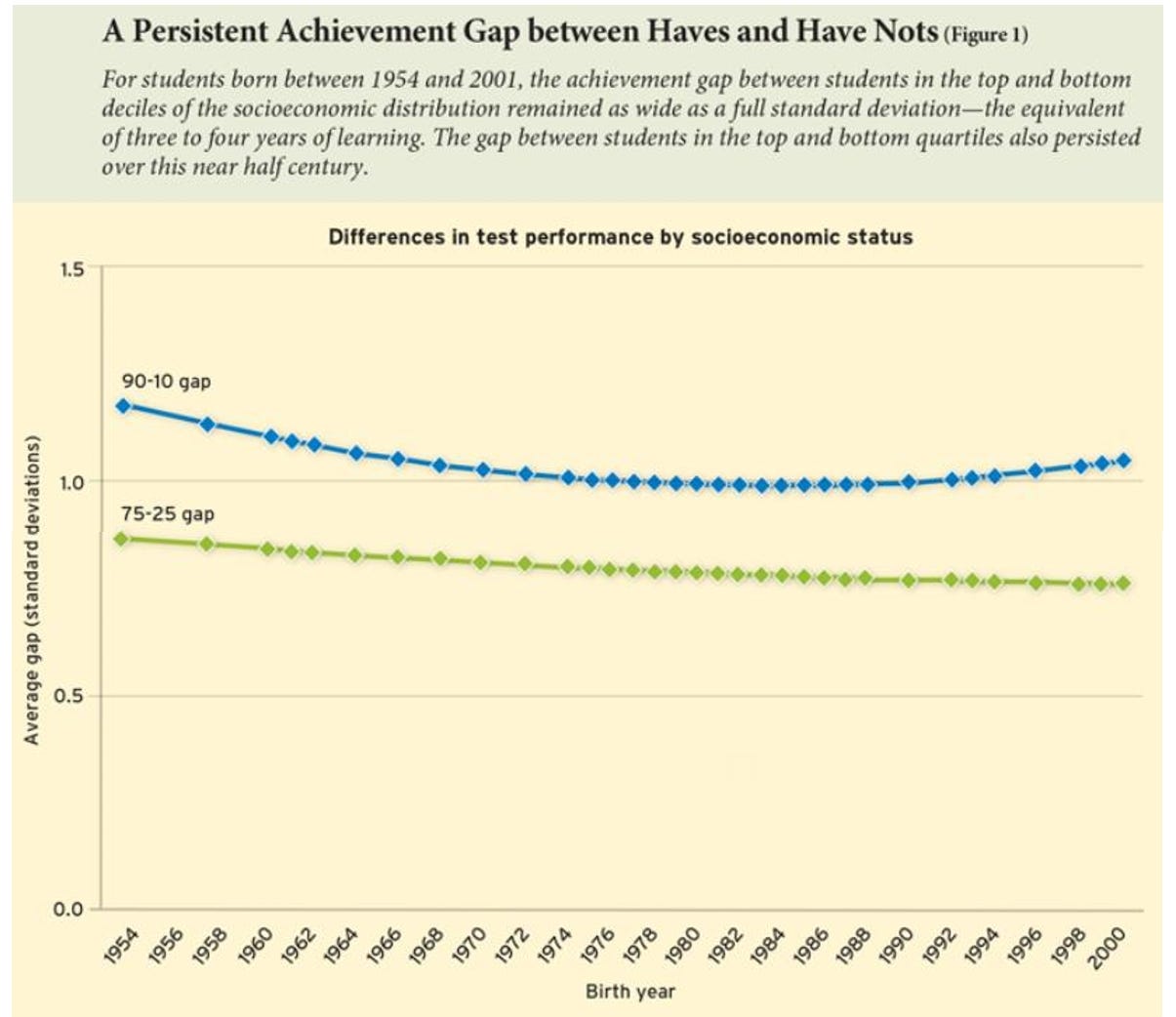

Despite large increases in education funding, the achievement gap between students in the top and bottom income deciles has persisted (and there are disproportionately large numbers of low-income blacks and Hispanics).

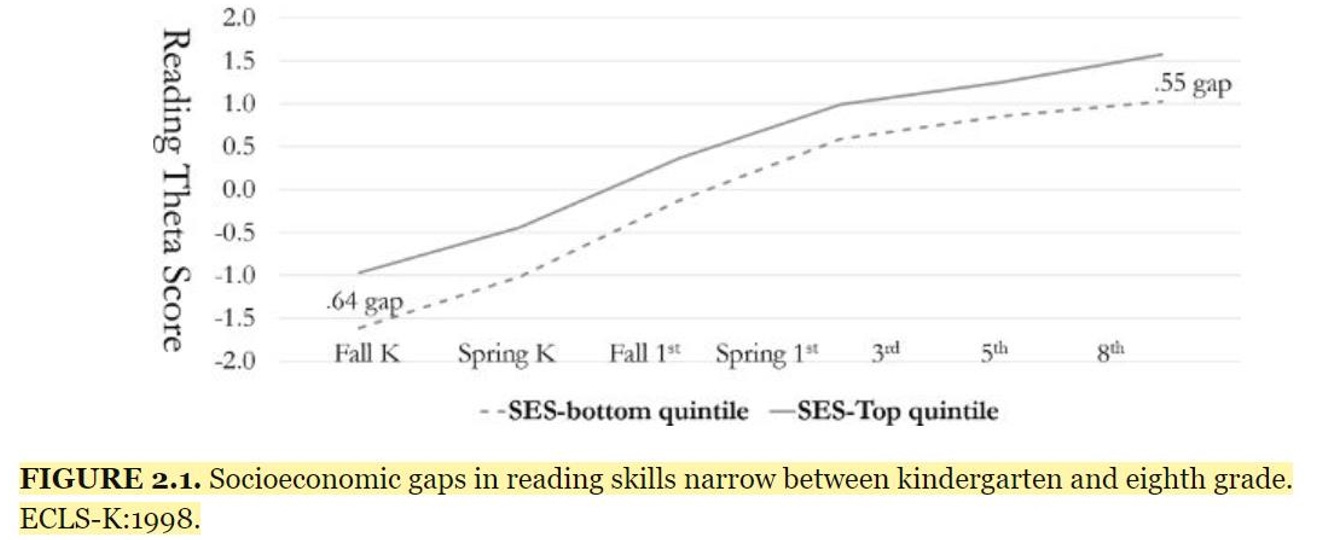

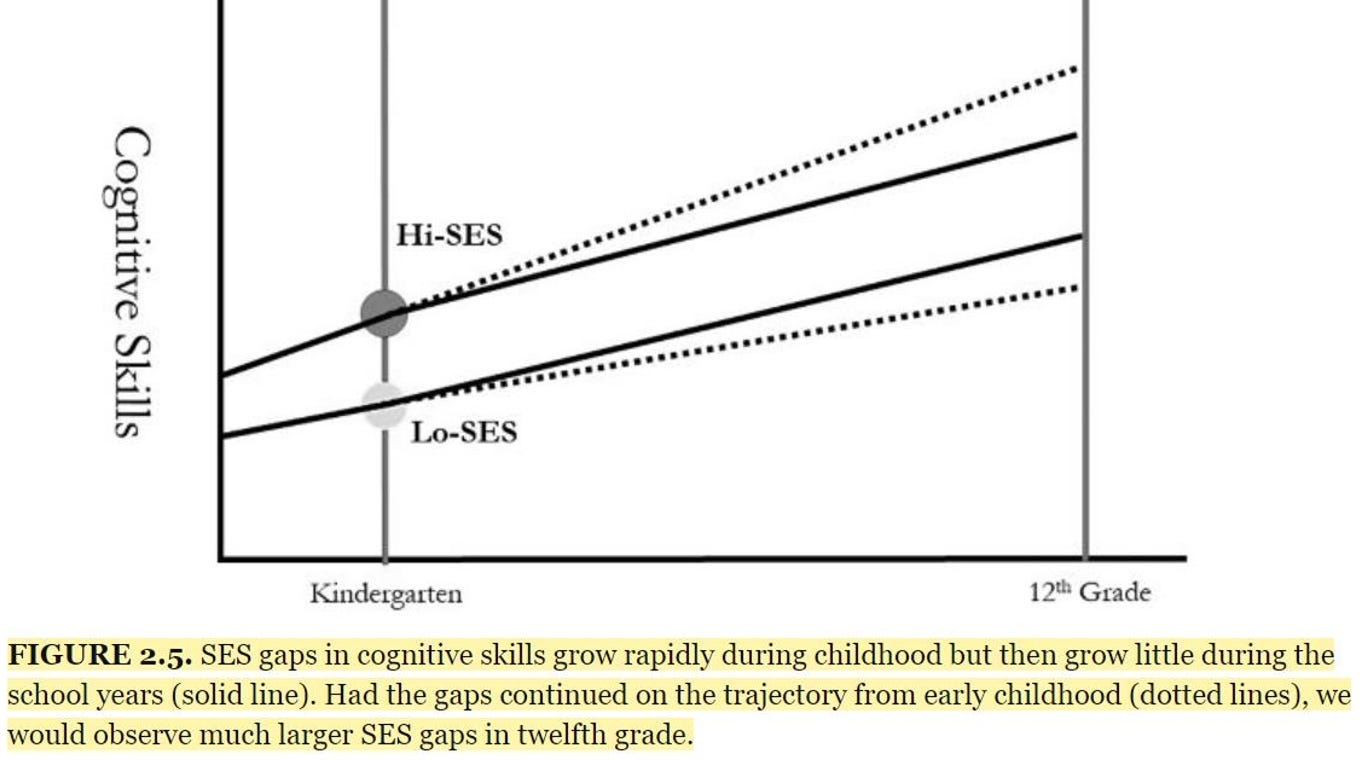

Douglas Downey, in his book How Schools Really Matter, describes how education gaps between lower- and higher-income students start well before kindergarten, and continue throughout their school time, with increases in learning gaps increasing over the summers.

Downey points out that students in public school generally only spend 13% of their waking hours in school, and so influences outside of school dominate learning patterns, including whether or not there are two parents in the home to help with education. As Downey writes:

Consider the following scenario: a disadvantaged child endures a student/teacher ratio of 25:1 while an advantaged child enjoys a 15:1 ratio—a 40 percent smaller child/adult ratio at school. But with three siblings and a single parent, the disadvantaged child’s adult/child ratio at home (1:4) is even worse (relatively) than the advantaged child who has one sibling and two parents (1:1). The disadvantaged child’s relative disadvantage at school, therefore, is smaller, where the child/adult ratio is only 40 percent worse, than at home, where the child/adult ratio is four times as large.

There’s also evidence that when more advanced and less advanced children are exposed to the same lessons, advanced students may also tend to learn less than they might have otherwise if they had been able to be exposed to more advanced learning. As Downey writes:

Schools expose children with a wide range of skills to roughly similar material—what I’ll call “curriculum consolidation.” Social scientists may be more familiar with the term “curriculum differentiation,” referring to school practices in which some children are exposed to different material and learning conditions than others, such as ability grouping, tracking, and retention practices. But schools also consolidate children’s learning experiences, grouping them together even when their skills are disparate. For example, schools can organize children in many ways, but children’s chronological age is the default basis upon which children are typically grouped. This simple policy of organizing children around age is something that we consistently do, but then forget what an important role it likely plays in reducing inequality [that is, reducing the performance of potententialy more advanced kids].

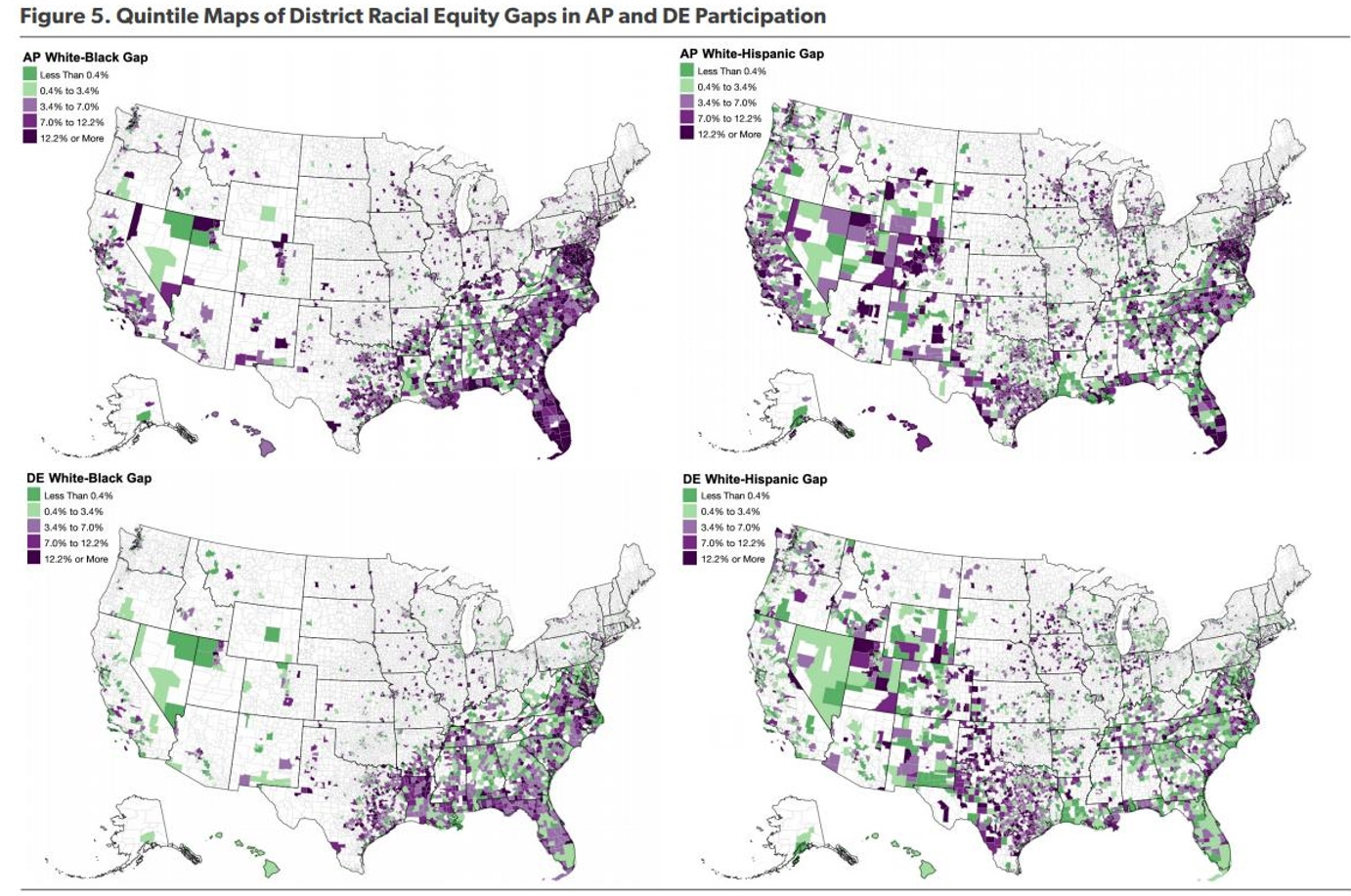

The racial gap in high school participation in Advanced Placement classes and dual enrollment classes (college classes open to high school students) is large, and does not seem to be lessened by policies that financially support and encourage the taking of such classes. Researchers have found that:

By mapping school districts nationwide, we find that the vast majority of districts have racial enrollment gaps in both programs, with wider gaps in AP than DE [dual-enrollment courses] … [T]he most striking finding from this category of predictors is that a set of factors that is correlated with greater AP participation overall (Table 2)— namely, proportions of students enrolled in urban schools, proportions of students enrolled in gifted and talented programs, average per-pupil instructional expenditures among high school students, and more AP course offerings—is also associated with wider AP racial enrollment gaps for, in most cases, black and Hispanic students. Finally, states with stronger accountability measures for access and student outcomes [generally, measures that encourage offering AP and DE classes along with financial help] have larger white-minority gaps for AP and DE compared with states with weak accountability measures.

The nonprofit Brightbeam looked at politically progressive and conservative cities to find any differences in racial education gaps between them, relying on criteria developed independently by political scientists Chris Tausanovitch and Christopher Warshaw, who pooled data from seven large surveys of U.S. public opinion to rank the nation’s biggest cities in terms of conservatism. Researchers then selected the 12 most conservative cities and the 12 least conservative cities from that list to establish the conservative and progressive cities that make up the base of their report. Brightbeam reports that “Progressive cities, on average, have achievement gaps in math and reading that are 15 and 13 percentage points higher than in conservative cities, respectively.”

There are also stark gender gaps in elementary school education and beyond, which are rarely mentioned in the media. One education scholar compiled the following list, entitled “For Every 100 Girls” (which used to be up on Education Week’s website but apparently no longer is):

An updated list of “For Every 100 Girls” statistics can be found here.

And an update of the chart as of January, 2020, can be found here.

The gender gap in favor of girls in reading ability is much greater than the gender gap in favor of boys in math ability.

Interestingly, teaching itself is a profession overwhelmingly dominated by women. As Alia Wong writes in the Atlantic magazine:

the gender distribution in the [teaching] profession has strangely grown more imbalanced, according to recently released data, largely because women are still pursuing teaching at far greater rates than men. According to the study, led by the University of Pennsylvania professor Richard Ingersoll, the nation has witnessed a “slow but steady” increase in the share of K–12 educators who are women. During the 1980–81 school year, roughly two in three—67 percent—public-school teachers were women; by the 2015–16 school year, the share of women teachers had grown to more than three in four, at 76 percent. (From 1987 to 2015, the size of the teaching force increased by more than 60 percent, from about 2.5 million to about 4.5 million, according to the recent report, which helps explain why the field tipped further female despite the rising number of men in the profession.) In the late 1970s, roughly a third of the women enrolled in U.S. colleges were majoring in education; today the share has dropped to 11 percent.

The cited report also states:

If the trend continues, we may see a day when 8 of 10 teachers in the nation will be female. An increasing percentage of elementary schools will have no male teachers. An increasing number of students may encounter few, if any, male teachers during their time in either elementary or secondary school. Given the importance of teachers as role models, and even as surrogate parents for some students, certainly some will see this trend as a problem and a policy concern.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at trends in metrics measuring teacher performance and other aspects of the teaching profession.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6