In this series of essays, we’ll explore education trends in pre-school and kindergarten through high school in America.

As has been reported, “The [proposed] six-year Biden [Administration] plan is designed to make free preschool available to all 3- and 4-year-olds, particularly low-income children. The proposal would establish a federal-state partnership offering states funds to expand public preschool programs to an estimated 6 million children.” Given the huge size and expense of such a program, it’s worth examining the evidence regarding the effectiveness of preschool programs to date.

Even the much-touted federal Head Start preschool program has been found to produce no long-term gains for children. The Head Start Impact Study, a large randomized study involving over 5,000 children, found in its final 2012 report that “In summary, there were initial positive impacts from having access to Head Start, but by the end of the 3rd grade there were very few impacts found for either cohort in any of the four domains of cognitive, social-emotional, health and parenting practices.”

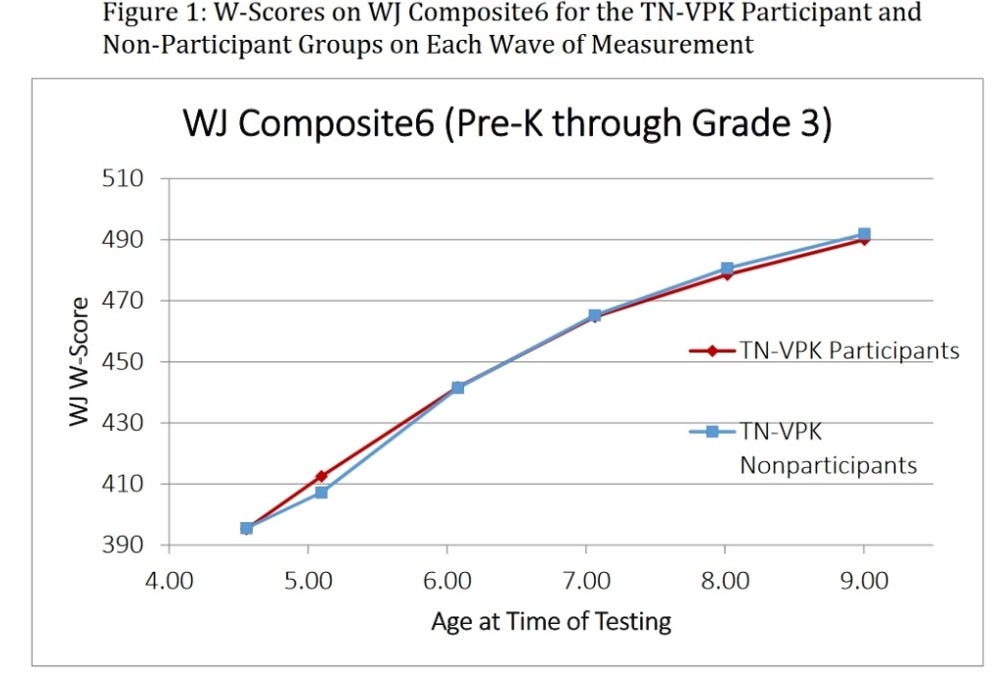

A comprehensive study of participation in pre-school programs in Tennessee showed no improvement in test scores over other control groups (and even some diminished scores over time).

The Vanderbilt University researchers have been running that long-term study on Tennessee’s state pre-K program and following 2,990 low-income children. The preschool program was oversubscribed, so researchers followed applicants who ended up in a preschool program and compared them to those who were turned away, meaning all the children had parents motivated to sign them up for pre-K (which makes them a statistically appropriate control group). The Vanderbilt findings, published in the journal Developmental Psychology, found that “children randomly assigned to attend pre-K had lower state achievement test scores in third through sixth grades than control children, with the strongest negative effects in sixth grade” and that “A negative effect was also found for disciplinary infractions, attendance, and receipt of special education services, with null effects on retention.” As noted in the Wall Street Journal, “That more children needed special education is especially salient: Part of the progressive pitch is that government will spend less money on such interventions later if it shells out for pre-K. Don’t count on it.”

Evidence regarding longer-term benefits of preschool indicate those benefits derive not from the curriculum or teaching methods, but for purely social reasons in that preschool can free low-income parents from childcare duties, give them the time to get a job or find better jobs, and improves parents’ human capital, with all the relevant follow-on effects. And if the home environment of a child is unusually bad, preschool gives the child some time outside the home environment and socializes them into a more “normal” way of life.

A February 2021 review of the academic literature by Max Eden at the Manhattan Institute finds that academic gains from Head Start fade within several years; that preschool experiments that showed better results were highly intensive or had only dozens of students; and that in Quebec, even children in two-parent families showed more hyperactivity and aggression after a state subsidy lured them into third-party childcare.

Regarding government-funded pre-K programs, researchers at the Brookings Institute previously found that:

There is a strong and politically bipartisan push to increase access to government-funded pre-K. This is based on a premise that free and available pre-K is the surest way to provide the opportunity for all children to succeed in school and life, and that it has predictable and cost-effective positive impacts on children’s academic success. The evidence to support this predicate is weak. There is only one randomized trial of a scaled-up state pre-K program with follow-up into elementary school. Rather than providing an academic boost to its participants as expected by pre-K advocates, achievement favored the control group by 2nd and 3rd grade. It is, however, only one study of one state program at one point in time. Do the findings generalize? The present study provides new correlational analyses that are relevant to the possible impact of state pre-K on later academic achievement. Findings include: no association between states’ federally reported scores on the fourth grade National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in various years and differences among states in levels of enrollment in their state’s pre-K program five years earlier than each of those years (when the fourth-graders taking NAEP would have been preschoolers) …

Under the most favorable scenario for state pre-K that can be constructed from these data, increasing pre-K enrollment by 10 percent would raise a state’s adjusted NAEP scores by a little less than one point five years later and have no influence on the unadjusted NAEP scores. Unabashed enthusiasts for increased investments in state pre-K need to confront the evidence that it does not enhance student achievement meaningfully, if at all. It may, of course, have positive impacts on other outcomes, although these have not yet been demonstrated. It is time for policymakers and advocates to consider and test potentially more powerful forms of investment in better futures for children.

As Derek Thompson has explained, “The evidence of state pre-K effectiveness has gotten worse over the last 50 years … [E]ither pre-K is getting worse, or we're getting better at measuring how ineffective it is at raising achievement,” pointing to the most recent research study that showed the following chart tracking the effect size found by various studies of pre-school programs over the years.

Regarding the controlled Tennessee preschool study, as Professor Peter Gray points out, preschools that try to impose academic programs on very young children seem to even increase the rate of diagnosis for learning disorders and school misbehavior:

By 6th grade, 14.6% of the children in the pre-K group, compared to 8.4% in the control group, had been diagnosed as having a learning disorder sufficient to require an IEP (Individualized Education Program). Stated differently, those in the pre-K group were 74% more likely to have been diagnosed with a learning disorder than those in the control group. (Parenthetically, I note that the researchers also used a different way of analyzing the results, in which the observed percentages were weighted to account for differences in the demographic profiles of those in the experiment and those in the full state-wide program. When this was done, the difference was even greater: The pre-K graduates were a bit more than twice as likely to have been diagnosed as learning disordered compared to the controls.) By 6th grade, 27.3% of the pre-K group, compared to 18.5% of the controls, had a record of at least one school rule violation. Moreover, 16.1% of the pre-K group, compared to 10.9% of controls, had a record of at least one major offense (such as fighting or bringing a weapon to school). Stated differently, by both indices, those in the pre-K group were 48% more likely to have committed a behavioral offense at school than those in the control group … The most striking finding in the study, to me, is the large increase in diagnosed learning disorders in the pre-K group. It seems possible that this increase is the central finding, though the authors of the report don’t make that claim. Previously I’ve discussed evidence that learning disorders can be produced by early academic pressure (here) and evidence that being labeled with a learning disorder can, through various means, become a self-fulfilling prophesy and result in poorer academic performance than would have occurred without the diagnosis (here).

Evidence also shows that the stress experienced by very young children when separated from their parents, if experienced over longer periods of time, can lead to negative results, as described by Katharine Stevens and quoted in a previous essay.

Research also shows that the television show Sesame Street prepared children for school as well as pre-school programs did (and at the much lower cost of about $5 per child per year).

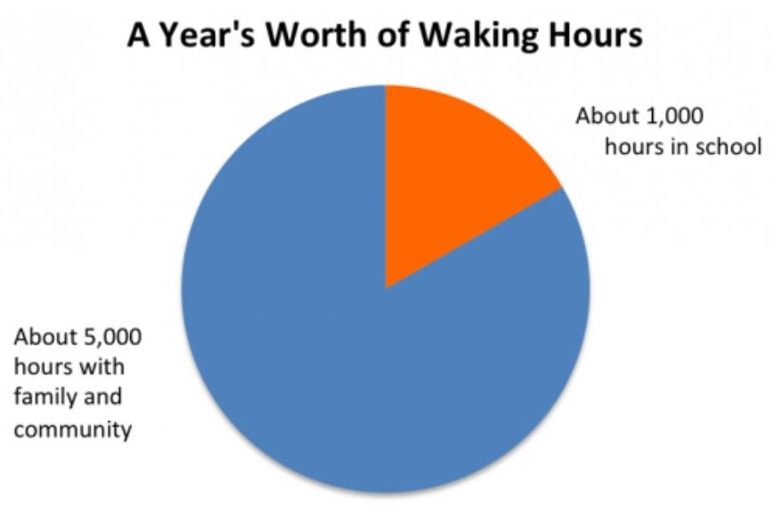

The much greater influence of the time parents spend with kids over the time kids spend in school as it relates to kids’ future success derives from the fact that each year consists of about 6,000 waking hours and children in America, on average, spend only about 1,000 of them in school (that is, 16% of their waking hours). The rest of the time is spent with their families and communities.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at student testing trends as kids get older.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6