Trends in Higher Education – Part 2

How the cost of higher education lowers young people’s life prospects.

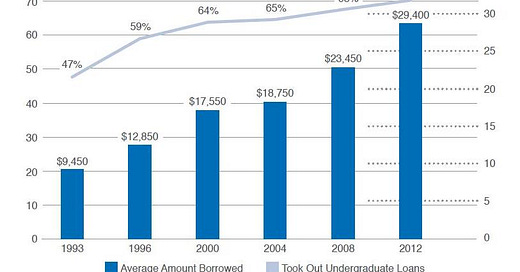

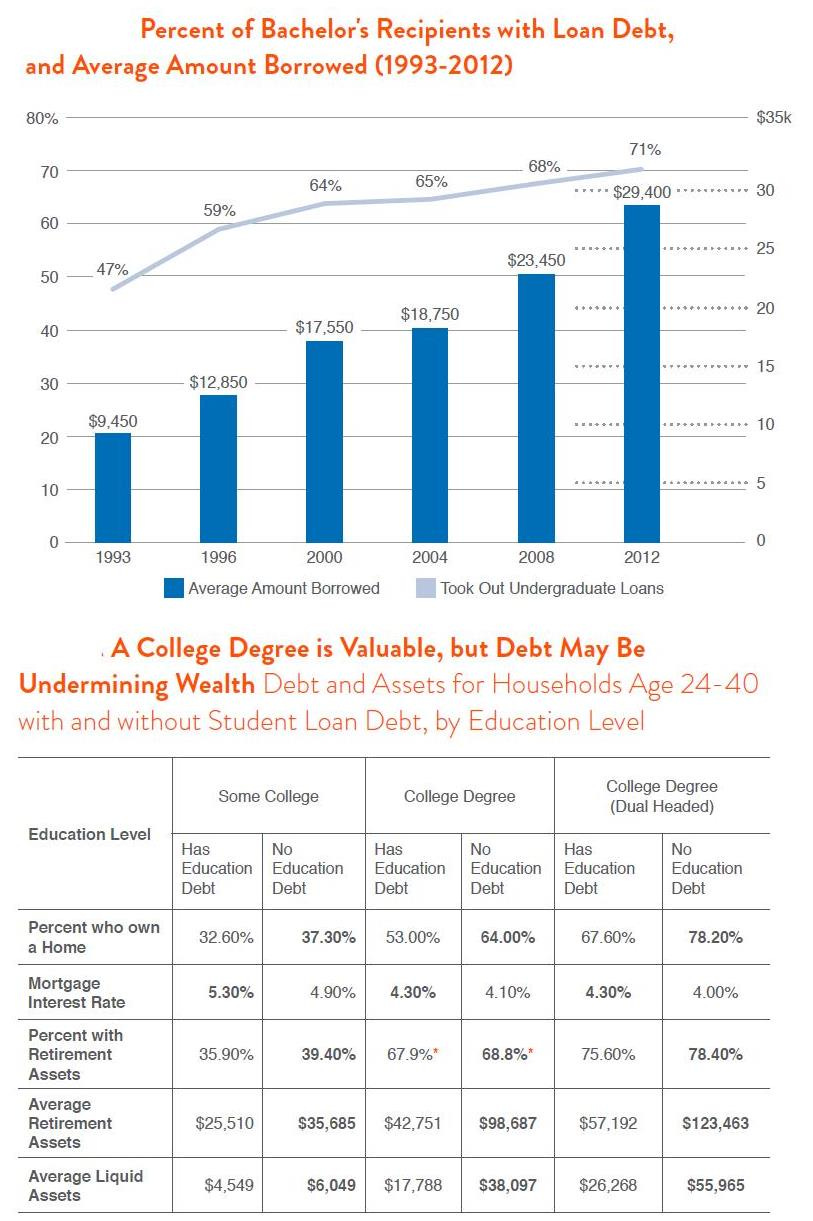

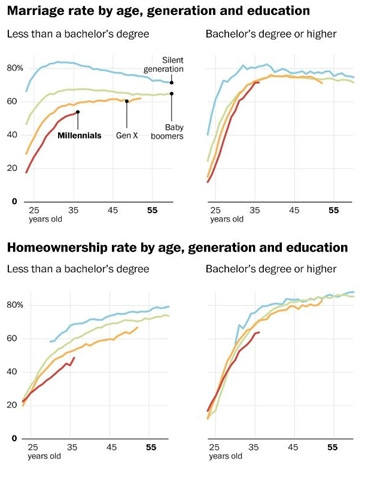

The percent of bachelor’s recipients with loan debt has grown along with the average amount borrowed, and the added debt is making it harder for people with student loan debt to own a home, obtain loans, create retirement assets, and liquid assets.

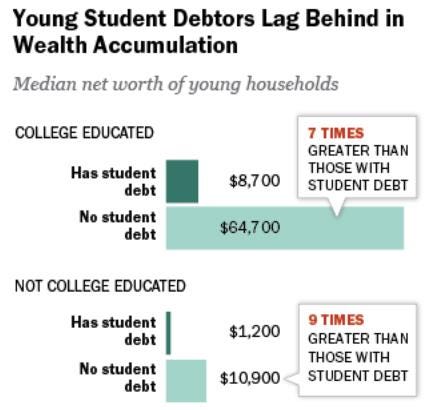

In 2014, households headed by a young, college-educated adult without any student debt obligations had about seven times the typical net worth of households headed by a young, college-educated adult with student debt.

As Alex Tabarrok points out:

[T]he net college wage premium is not as large as it appears and inequality has been over-estimated. Remarkably Enrico Moretti (2013) estimates that 25% of the increase in the college wage premium between 1980 and 2000 was absorbed by higher housing costs. Moreover, since the big increases in housing costs have come after 2000, it’s very likely that an even larger share of the college wage premium today is being eaten by housing. High housing costs don’t simply redistribute wealth from workers to landowners. High housing costs reduce the return to education reducing the incentive to invest in education. Thus higher housing costs have reduced human capital and the number of skilled workers with potentially significant effects on growth.

Researchers at the Federal Reserve have found that:

The college income premium—the extra income earned by a family headed by a college graduate over an otherwise similar family without a bachelor’s degree—remains positive but has declined for recent graduates. The college wealth premium (extra wealth) has declined more noticeably among all cohorts born after 1940. Among non-Hispanic white family heads born in the 1980s, the college wealth premium is at a historic low; among all other races and ethnicities, it is statistically indistinguishable from zero. Using variables available for the first time in the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances, we find that controlling for the education of one’s parents reduces our estimates of college and postgraduate income and wealth premiums by 8 to 18 percent. Controlling also for measures of a respondent’s financial acumen—which may be partly innate—, our estimates of the value added by college and a postgraduate degree fall by 30 to 60 percent. Taken together, our results suggest that college and post-graduate education may be failing some recent graduates as a financial investment.

The Federal Reserve has linked rising student debt to a drop in homeownership among young Americans and the flight of college graduates from rural areas.

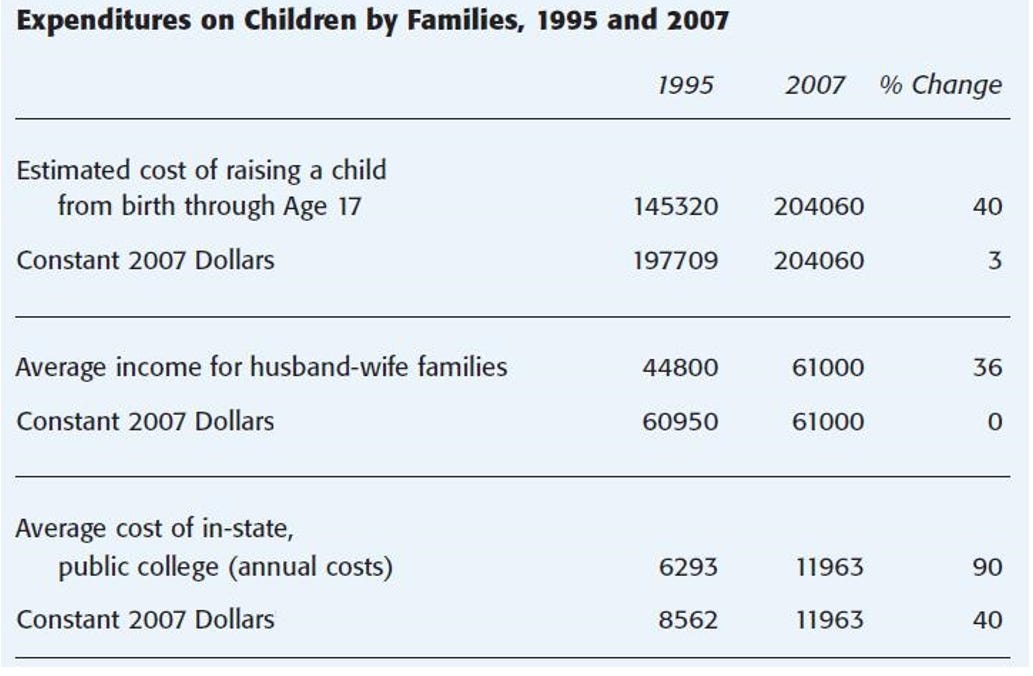

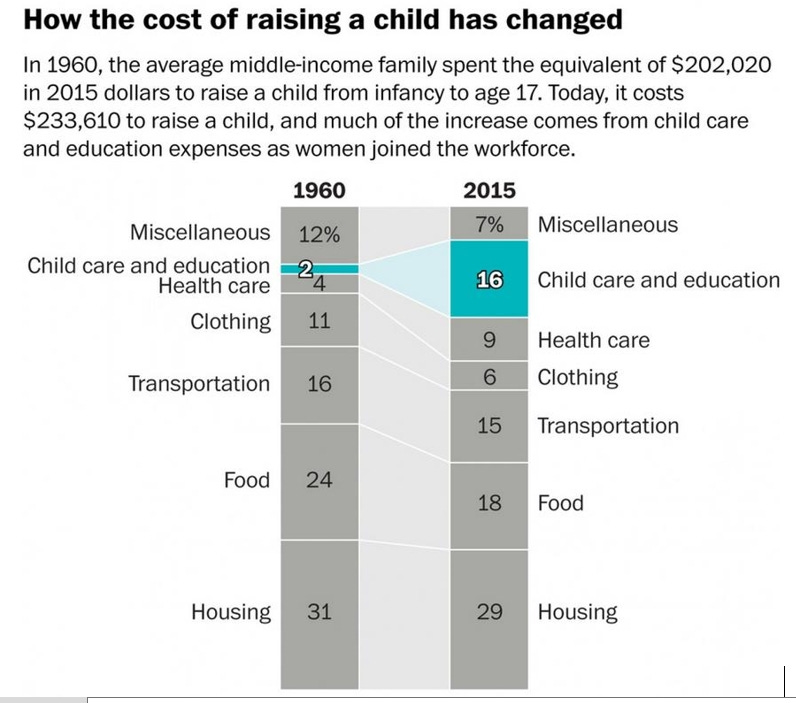

These dynamics inhibit financial well-being and delay family formation. Ten years ago, one in five young adults reported they had postponed getting married or having a baby, or moved back in with their parents, due to economic conditions, including student debt. Further, the rising cost of a college education has significantly contributed to the rising costs of raising a child generally, and as children become more expensive to raise, fewer people can afford to raise them.

The cost of raising children today is at record highs, driven by the costs of things that are heavily regulated by the government.

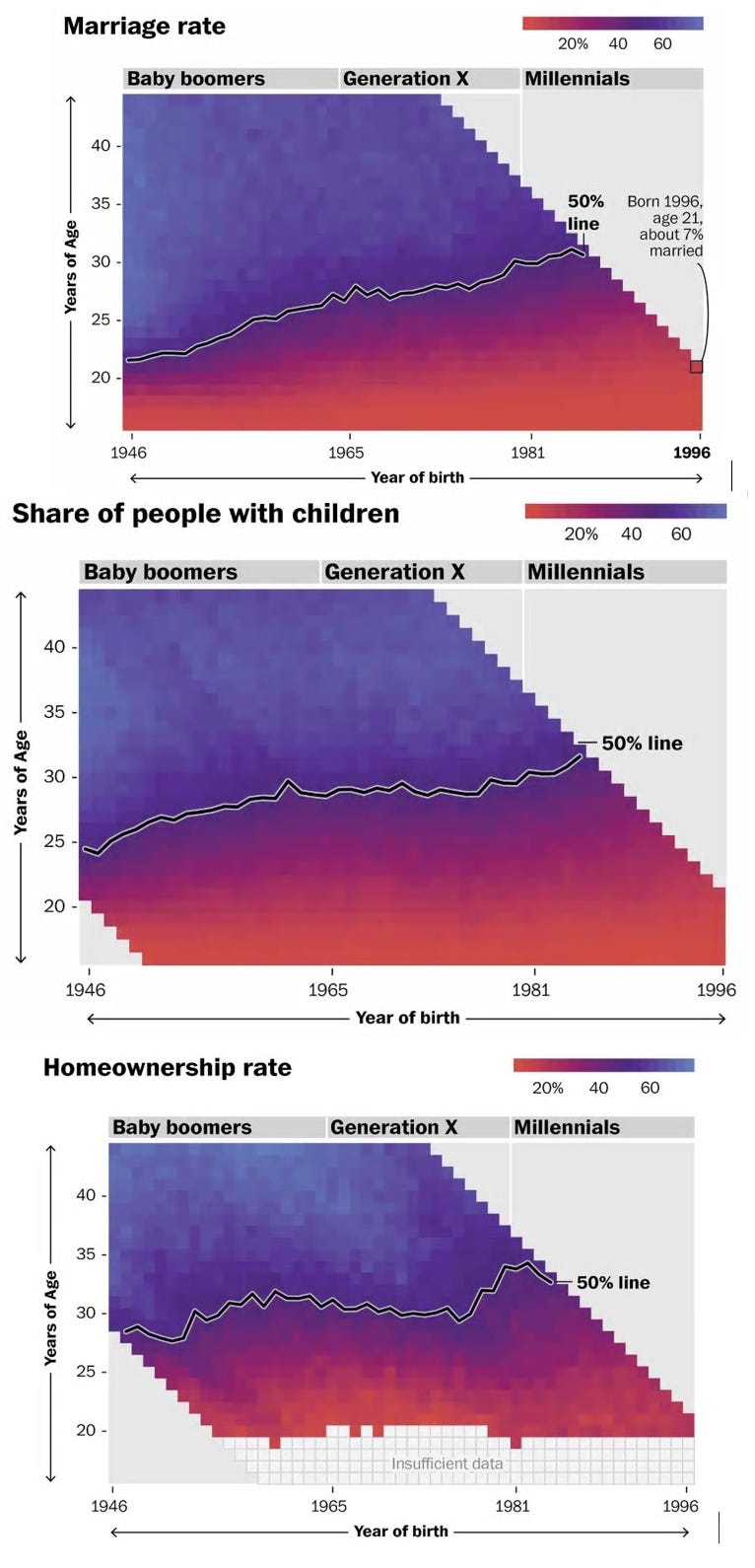

Evidence shows that all the major life milestones — marriage, children, homeownership — have arrived measurably later for millennials than for the three previous generations for which we have comparable data.

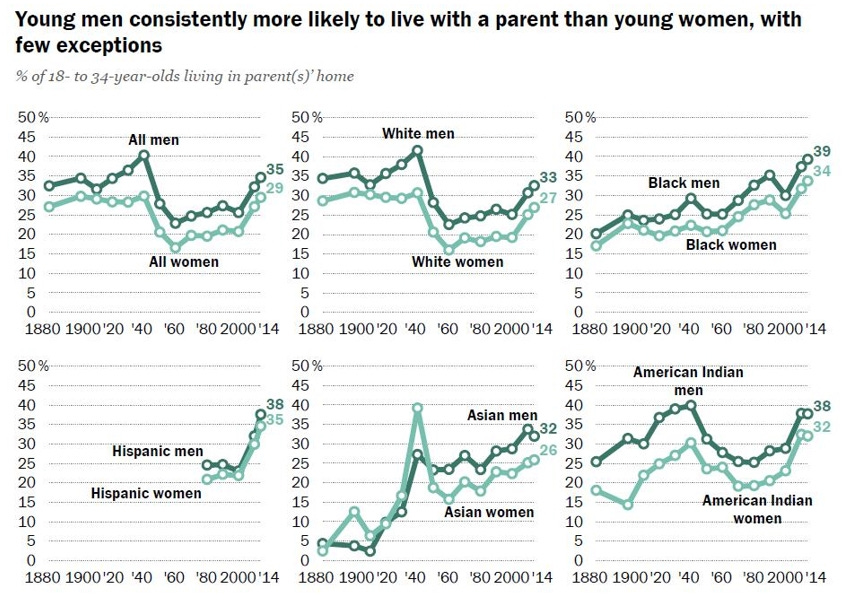

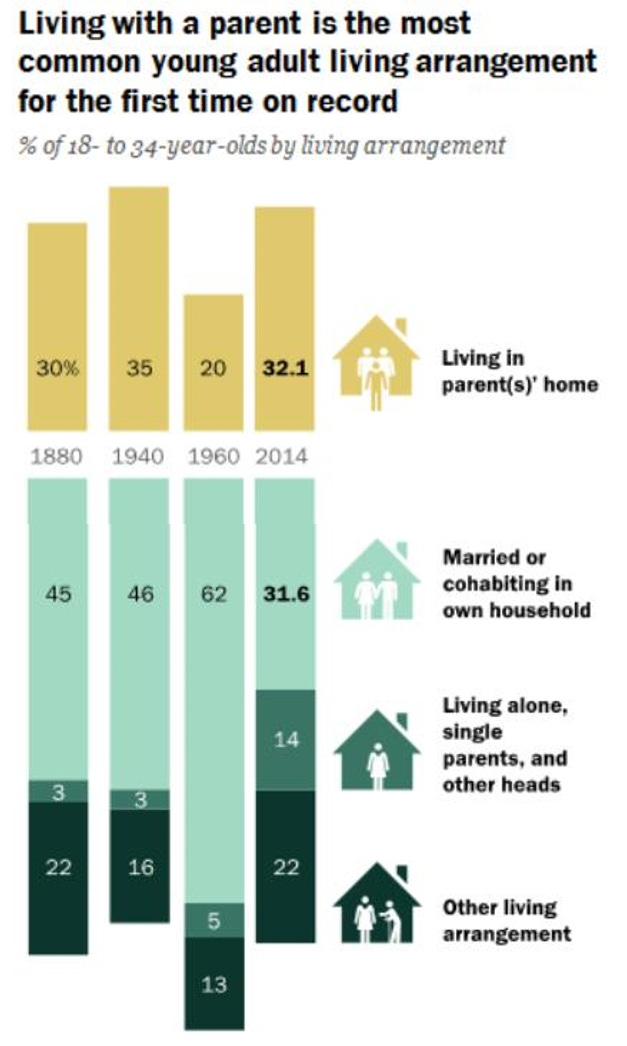

A significantly increasing number of middle-aged parents are now providing primary financial support for their own adult children for reasons other than to pay for higher education expenses, and more parental financial support is now going to their grown children rather than their aging parents. The percentage of married couples living in a parent’s home has returned to levels not seen since the turn of the 20th century. And more people generally are living with their parents, and not with a spouse or partner, especially young men.

In 2016, living with a parent was the most common young adult living arrangement for the first time on record.

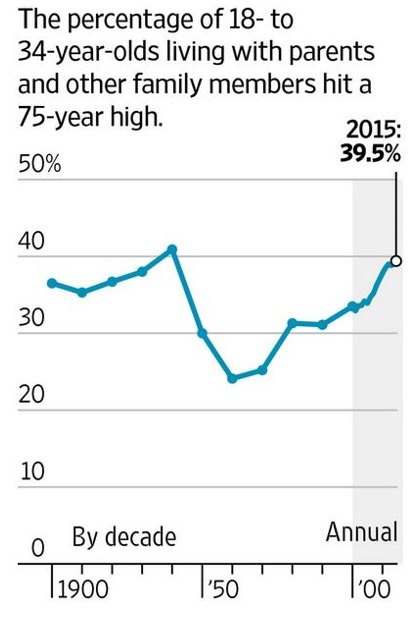

Almost 40 percent of young Americans were living with their parents, siblings or other relatives in 2015, the largest percentage since 1940, according to an analysis of census data.

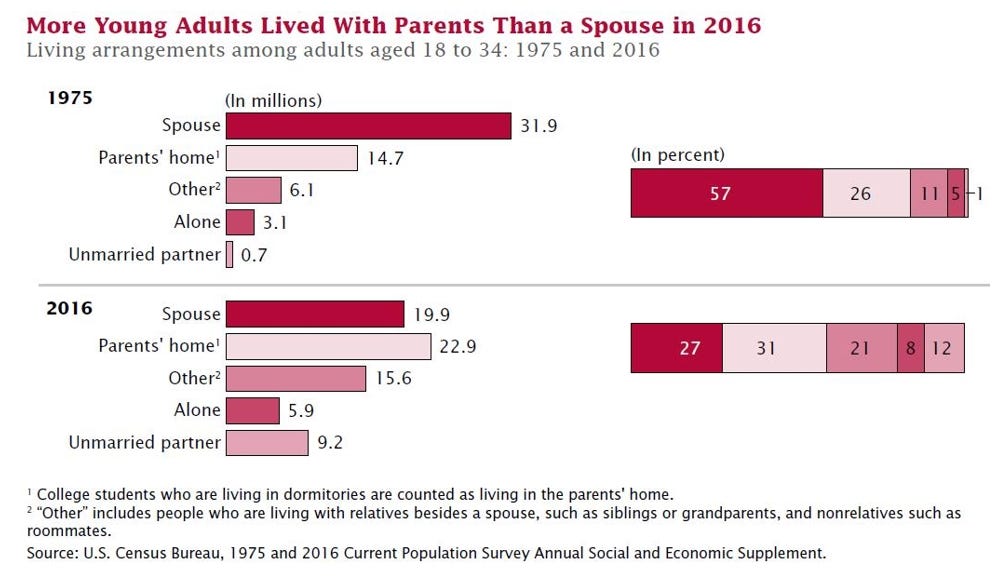

The Census Bureau has found that many more young adults lived with their parents in 2016 compared to 1975.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at the increasingly lower returns of higher education.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

The graph of home ownership, mortgage rates and retirement asset value is fascinating. However, it contradicts the main point here that income gaps don't justify student loan debt.

I can see my liberal friends using this graph to make that point.