Skin in the Game – Part 1

Might people with kids care more about the future prospects of the next generation?

In previous essays I described how mandatory federal entitlement programs automatically increase future spending in the absence of legislative reforms. In the meantime, the ever-increasing debt is foisted on future generations who will have to pay the costs of that debt, even as more and more younger people are working less (and even receiving entitlement benefits of their own) while the older population continues to receive its growing share of entitlement benefits. What might help explain how this perverse dynamic is allowed to continue?

Policymakers Don’t Have Skin in the Game

In his book “Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life,” Nassim Taleb describes the various ramifications of the concept of “skin in the game,” which provides that if a decisionmaker doesn’t stand to suffer personal costs as a result of a bad decision, that decisionmaker is more likely to make mistakes, the costs of which will be felt by others. Taleb traces the concept to Yiddish proverbs: “You can’t chew with somebody else’s teeth” and “Your fingernail can best scratch your itch.” The concept makes intuitive sense, but its ramifications are often overlooked.

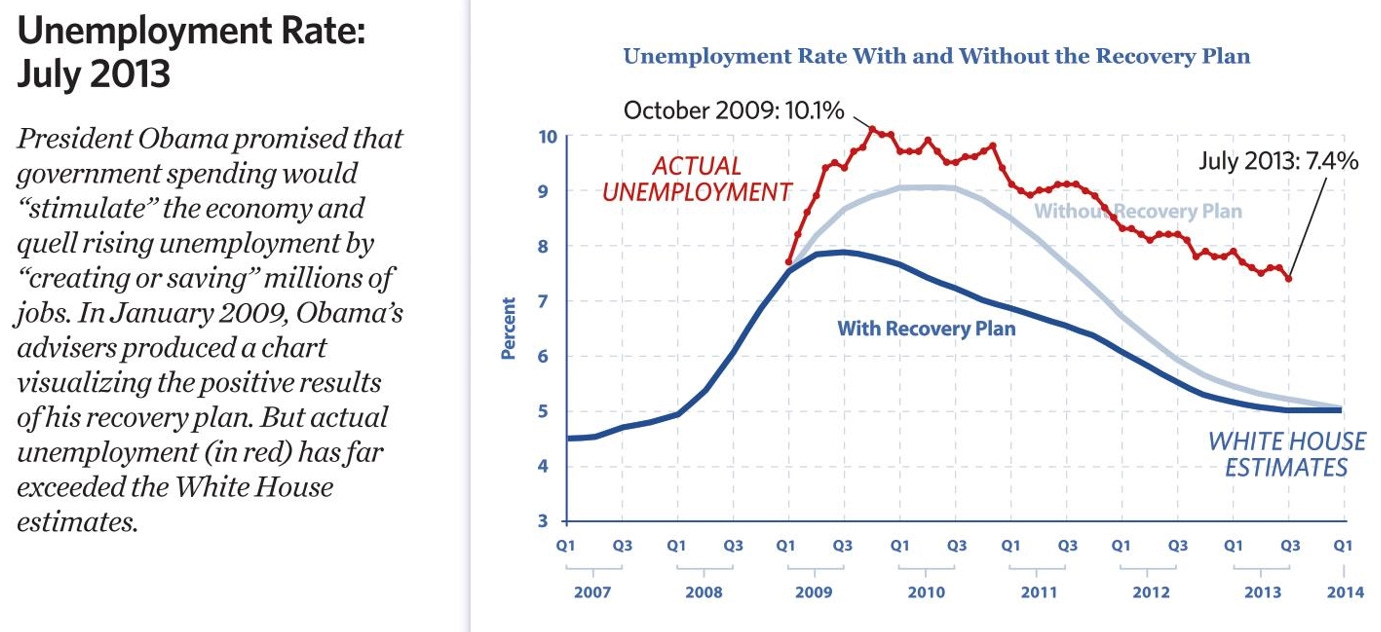

Policymakers in the public sector tend to get paid no matter how bad the results of the policies they impose, which of course tends to lead to more bad policy results. For example, government spending has generally not lived up to its promises. The chart below is from a report by former Obama economic advisors Christina Romer and Jared Bernstein entitled “The Job Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Plan” (January 10, 2009) (apparently no longer available on the internet), indicating how much lower they said the unemployment rate would be if Congress passed a $1 trillion stimulus bill, compared to what it would be if Congress did nothing.

And the chart below shows what the unemployment rate actually was after the stimulus law was enacted, showing the unemployment rate actually rose higher than what President Obama’s advisers said would be the case if Congress had done nothing.

As Taleb writes (in his sometimes hyperbolic style): “we end up populating what we call the intelligentsia with people who are delusional, literally mentally deranged, simply because they never have to pay for the consequences of their actions.” And not having to pay for the consequences of one’s actions forestalls learning from mistakes as well. As Taleb writes:

Now, if you are going to highlight only one single section from this book, here is the one. The interventionista case is central to our story because it shows how absence of skin in the game has both ethical and epistemological effects (i.e., related to knowledge). We saw that interventionistas don’t learn because they are not the victims of their mistakes … The same mechanism of transferring risk also impedes learning. More practically, You will never fully convince someone that he is wrong; only reality can.

For example, research has shown that “Most of the persistent increase in unemployment during the Great Recession can be accounted for by the unprecedented extensions of unemployment benefit eligibility [at the time, 2007-2009].” Yet as this essay is being written, President Biden, in 2021, has proposed an even more disproportionate stimulus following the more recent COVID-19 pandemic. As former Obama Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers wrote in the Washington Post:

[W]hereas the Obama stimulus was about half as large as the output shortfall, the proposed Biden stimulus is three times as large as the projected shortfall … Wage and salary incomes are now running about $30 billion a month below pre-covid-19 forecasts, and this gap will likely decline during 2021. Yet increased benefit payments and tax credits in 2021 with proposed stimulus measures would total about $150 billion — a ratio of 5 to 1. The ratio is likely even greater for low-income individuals and families, given the targeting of stimulus measures … If the stimulus proposal is enacted, Congress will have committed 15 percent of GDP with essentially no increase in public investment to address these challenges. After resolving the coronavirus crisis, how will political and economic space be found for the public investments that should be the nation’s highest priority?

As the Wall Street Journal summarized the contents of the legislation:

All told, this generous definition of Covid-related provisions tallies some $825 billion. The rest of the bill—more than $1 trillion—is a combination of bailouts for Democratic constituencies, expansions of progressive programs, pork, and unrelated policy changes. Start with the $350 billion for state and local governments and cities and counties, even as state revenues have largely recovered since the spring. Democrats also changed the funding formula to ensure most of the dollars go to blue states that imposed strict economic lockdowns. Last year’s Cares Act distributed money mainly by state population, but much of the $220 billion for states in the new bill will be allocated based on average unemployment over the three-month period ending in December. Andrew Cuomo’s New York (8.2% unemployment in December) and Gavin Newsom’s California (9%) get rewarded for crushing their businesses, while Kristi Noem’s South Dakota (3%) is penalized for staying open. These windfalls come with few strings attached … Elementary and secondary schools get another $129 billion, whether they reopen for classroom learning or not. Higher education gets $40 billion. The CBO notes that since Congress already provided some $113 billion for schools—and as “most of those funds remain to be spent”—it expects that 95% of this new money will be spent from 2022 through 2028. That is, when the pandemic is over … There’s $39 billion for child care; $30 billion for public transit agencies; $19 billion in rental assistance; $10 billion in mortgage help; $4.5 billion for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance program; $3.5 billion for the program formerly known as food stamps; $1 billion for Head Start; $1.5 billion for Amtrak; $50 billion for the Federal Emergency Management Agency; $4 billion to pay off loans of “socially disadvantaged” farmers and ranchers; and nearly $1 billion in world food assistance.

As Summers further said this about the Biden Administration budget in 2021: “This is the least responsible macroeconomic policy we’ve had in the last 40 years.”

As Taleb writes:

if you believe that you are “helping the poor” by spending money on PowerPoint presentations and international meetings, the type of meetings that lead to more meetings (and PowerPoint presentations) you can completely ignore individuals—the poor become an abstract reified construct that you do not encounter in your real life.

And as much as the well-being of individuals alive today are overlooked by policymakers without skin in the game, the fate of future generations, not yet born, is wholly ignored.

Policymaker’s Lack of Skin in the Game Has Diminished the Next Generation’s Prospects

Taleb describes what’s known as a “tail risk”:

What is a tail? Take for now that it is an extreme event of low frequency. It is called a “tail” because, in drawings of bell-curve style frequencies, it is located to the extreme left or right (being of low frequency), and for some reason beyond my immediate understanding, people started calling that a “tail” and the term stuck. Hammurabi’s best known injunction is as follows: “If a builder builds a house and the house collapses and causes the death of the owner of the house—the builder shall be put to death.” For, as with financial traders, the best place to hide risks is “in the corners,” in burying vulnerabilities to rare events that only the architect (or the trader) can detect—the idea being to be far away in time and place when blowups happen. As one old alcoholic ruddy-faced English banker told me when I graduated from school, volunteering career advice: “I give long-term loans only. When they mature I want to be long gone. And only reachable long distance.”

The risks posed by a potential future debt crisis, explored in an earlier essay, are prime examples of the violation of Hammurabi’s injunction and what happens when policymakers don’t have skin in the game.

Responsible parents would be loathe to impose such risks on their own children. As Taleb writes, when it comes to incentives:

Modernity put it in our heads that there are two units: the individual and the universal collective—in that sense, skin in the game for you would be just for you, as a unit. In reality, my skin lies in a broader set of people, one that includes a family, a community, a tribe, a fraternity. But it cannot possibly be the universal … Things don’t “scale” and generalize, which is why I have trouble with intellectuals talking about abstract notions. A country is not a large city, a city is not a large family, and, sorry, the world is not a large village.

A family’s finances exist in the more predictable world of “microeconomics,” the study of the economic behavior of individual people and individual firms, where responsibility for poor economic decisions is felt quickly and personally. On the other hand, a nation’s finances exist in the world of “macroeconomics,” the much murkier place in which detached government officials claim to be able to predict for policy purposes the results of the interaction of all economic activities in an entire country. In one of his pithier moments, Taleb writes “Macroeconomics, for instance, can be nonsense since it is easier to macrobull***t than microbull***t -- nobody can tell if a theory really works.”

Elizabeth Stone is famously quoted as saying “Making the decision to have a child – it’s momentous. It is to decide forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body.” And as Nassim Taleb writes, “[s]kin in the game keeps human hubris in check.” And parents have skin in the game -- or more accurately, DNA in the game – in the form of their own children, which I surmise incentivizes them to be more supportive of policies that consider the well-being of future generations, at least more so than a childless person.

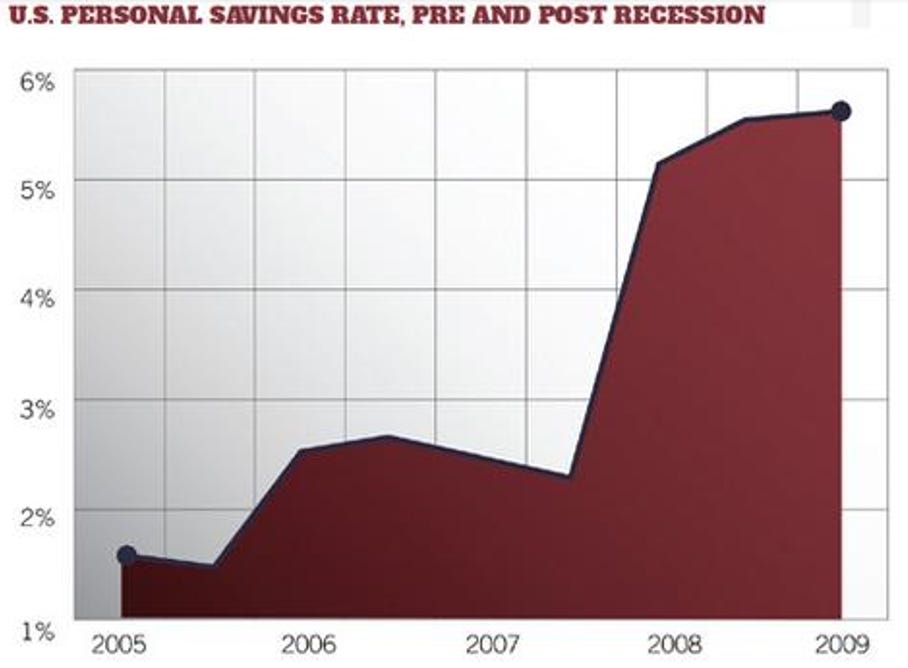

While the federal government has continued to spend more than it takes in through good times and bad, the American people generally (at the family level) have demonstrated an ability to save responsibly for future contingencies. For example, the personal savings rate rose during the 2007-2009 recession.

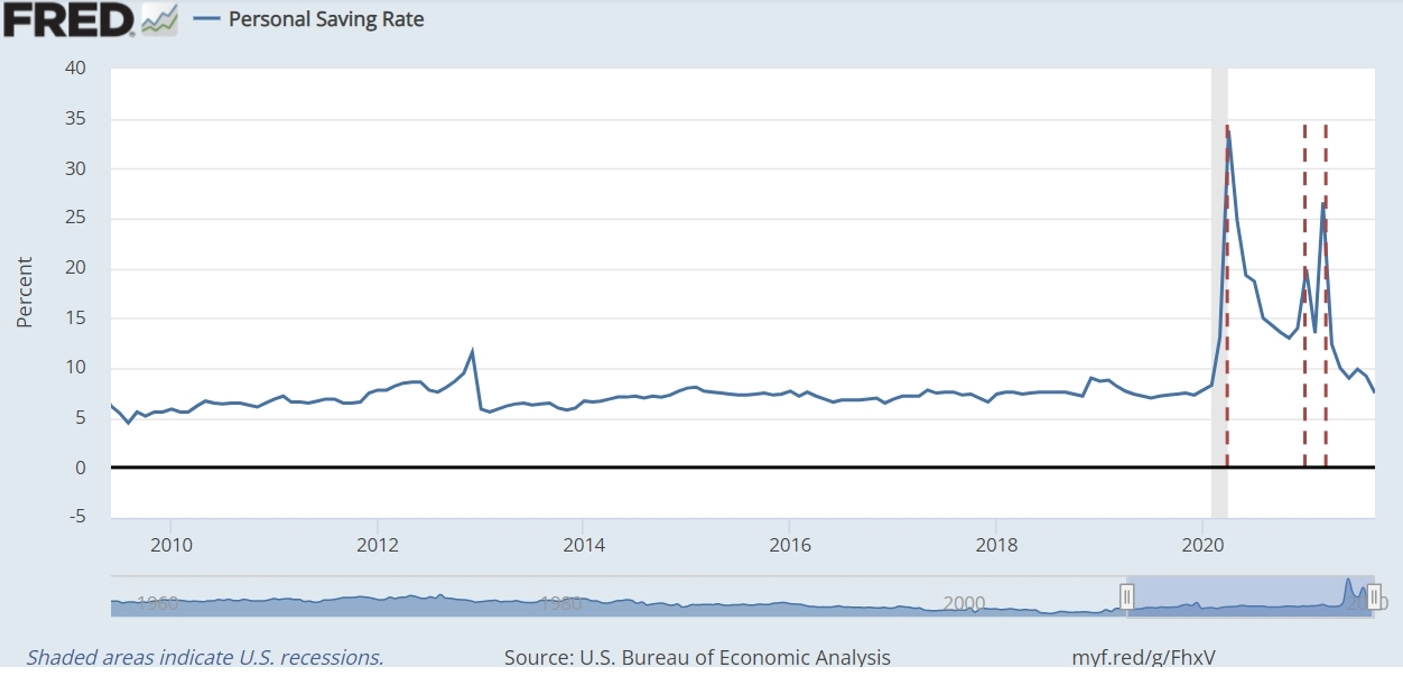

And individuals have also increased their personal savings during the more recent COVID pandemic. As the Federal Reserve Bank’s research arm reports, “the aggregate personal saving rate has actually increased since the start of the pandemic.”

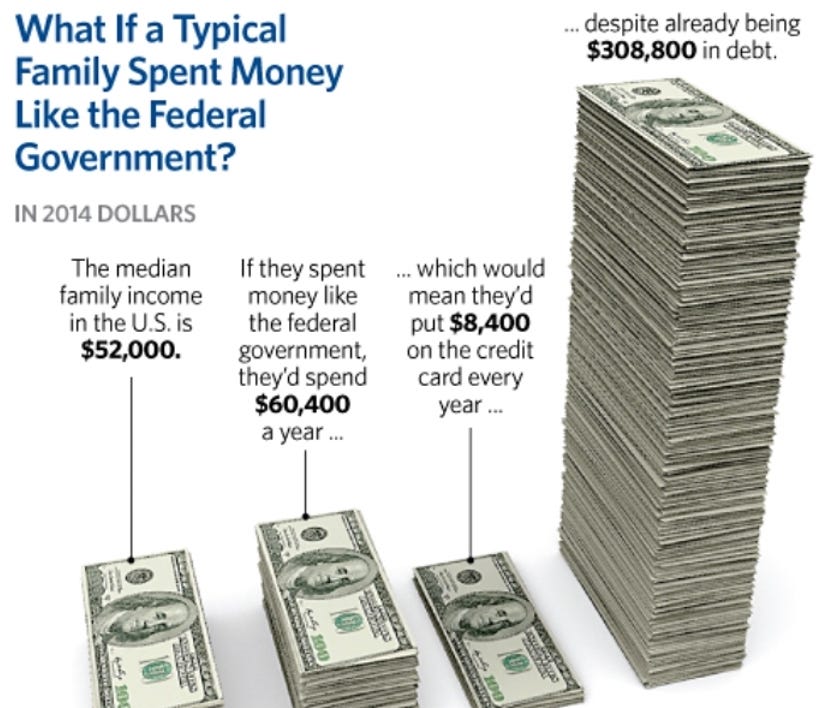

The federal government, however, has not tended to demonstrate similar restraint.

As Frederick Hess points out, at the individual level:

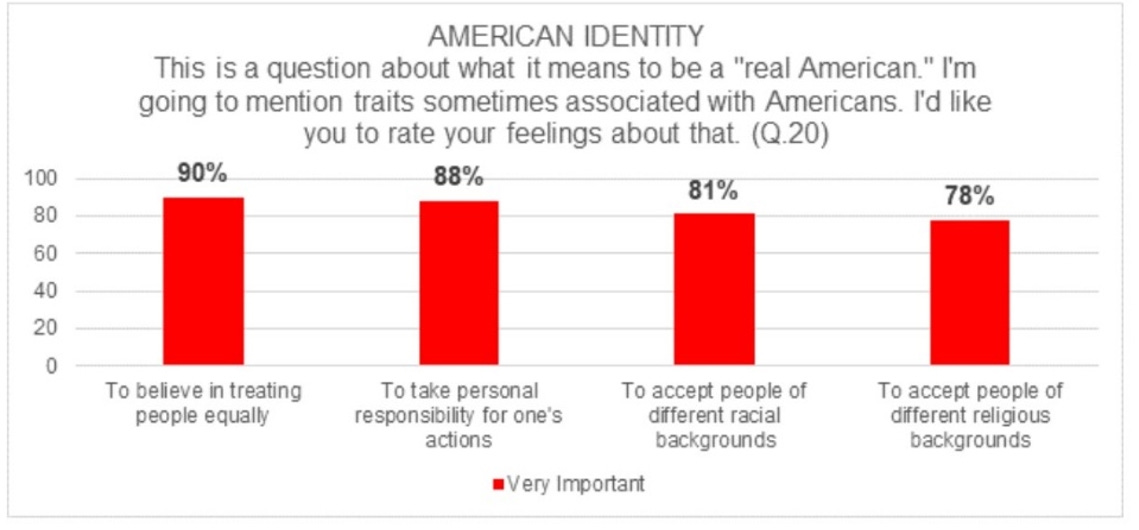

in 2018, a Grinnell College poll reported that 88% of respondents regard responsibility for one’s actions as a “very important” component of what it means to be a “real American,” right alongside “treating people equally” (which 90% regard as “very important”).

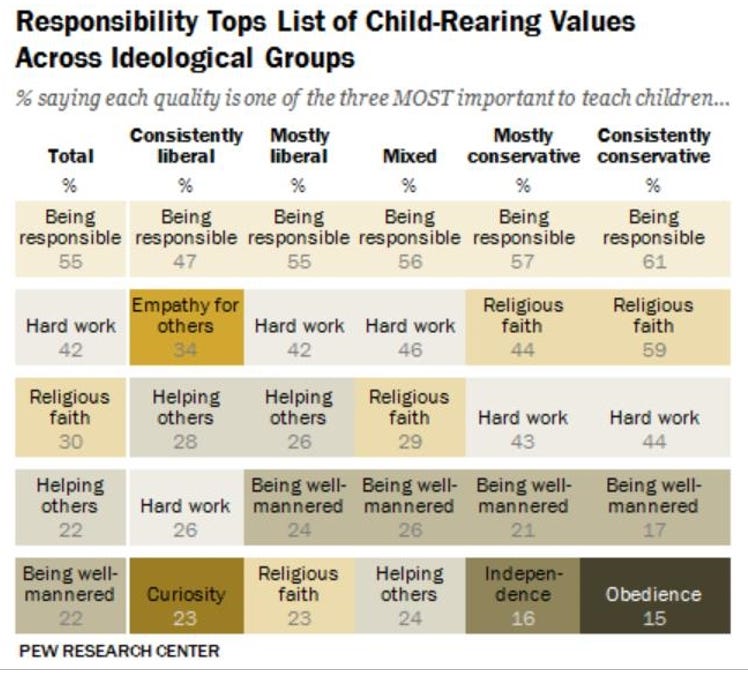

As Hess and R.J. Martin further point out: if one asks parents — of any race — what values they want their kids to learn, more than four out of five will similarly name concepts like “hard work” [and] “being responsible.”

And looking a little deeper, when asked which qualities are the most important to teach children, those who were “consistently conservative” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” more often than the average American. (Those who were “consistently liberal” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” less often than the average American.)

Of course, there are reasons a government like the United States can delay a reckoning for its debt that don’t apply to households. Government can simply print more money, for one, and they can float along on borrowed money as long as investors think there’s a good chance they’ll be paid back in the end. But those relative “advantages” of government have, over time, translated into increasingly complicated policies the dangers of which become more obscure as their complexity grows. As Taleb writes:

Things designed by people without skin in the game tend to grow in complication (before their final collapse). There is absolutely no benefit for someone in such a position to propose something simple: when you are rewarded for perception, not results, you need to show sophistication.

In many ways, though, personal ethics reflect public ethics (unless one has something to hide). As Taleb points out, “If your private life conflicts with your intellectual opinion, it cancels your intellectual ideas, not your private life … If a car salesman tries to sell you a Detroit car while driving a Honda, he is signaling that the wares he is touting may have a problem.”

So if so many people behave more responsibly in their private life, yet allow their elected leaders to govern so irresponsibly, what might explain that disconnect?

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5