The Federal Government on Spending Autopilot – Part 6

Proposals for reform -- part of a potential agenda for the next Congress.

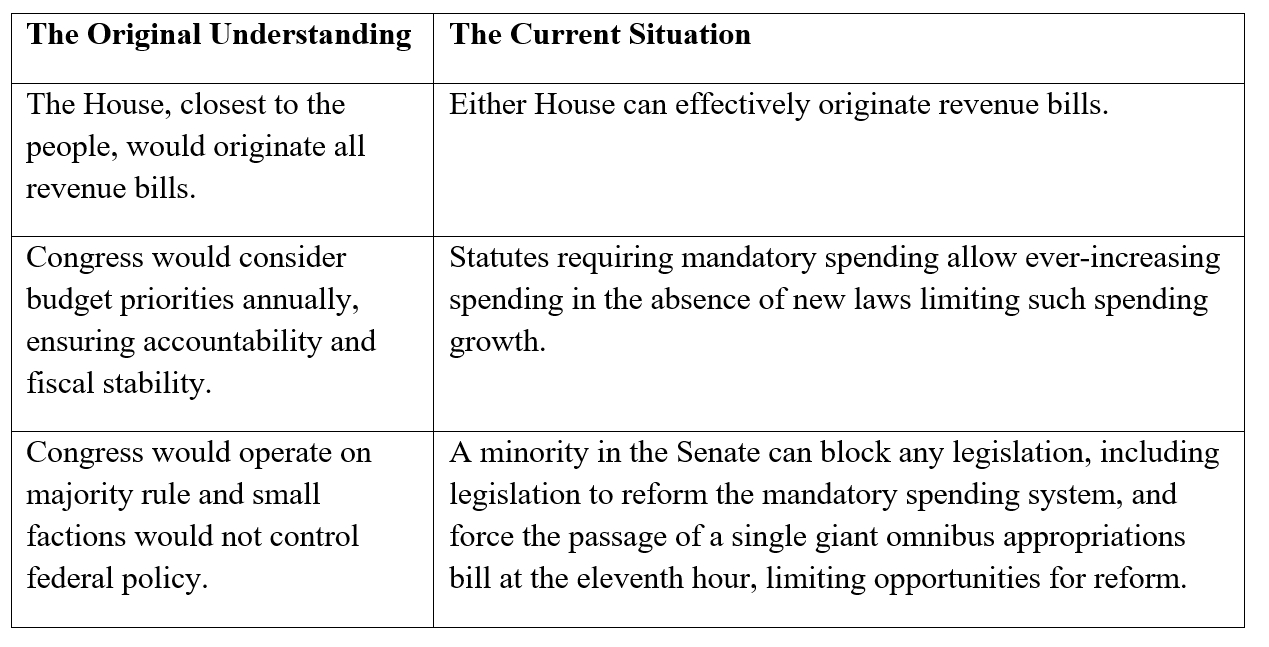

Previous essays have described how dramatically the current national fiscal situation deviates from the original understanding of the constitutional role of Congress, and in particular the constitutional role of the House of Representatives, in enacting the federal budget. That situation is summarized in the chart below.

In my last essay, I recommended a reform to Senate rules that would allow a simple majority of Senators to enact legislation reforming the current federal mandatory spending entitlement system. In this essay, I’ll propose some potential solutions to restoring the authority of the People’s House that focus on reforms that haven’t previously been considered by the House of Representatives.

● Prohibit automatic increases of payouts in both old and new mandatory spending programs through a federal statute requiring a fixed budget for them for a fixed amount of time. Because huge mandatory spending operates on auto-pilot absent Congressional action, the debt will simply be added to annually without end. To remedy this, a law should be enacted prohibiting automatic increases of payouts in both old and new mandatory federal spending programs by requiring a fixed budget for them for a fixed amount of time. For instance, each health care program could be put within a budget, requiring the empowering of someone, somewhere -- through vouchers, price controls, bundling payments, or other methods -- to stay within the budget. That way, Congress would be required to periodically revisit programs and their cost, and make decisions about fiscal priorities rather than punting those decisions down the road through inaction. All mandatory spending programs should operate within a budget. That would contrast radically with past practice, since major mandatory spending entitlement programs are generally effectively open-ended.

● Create safeguards to ensure more fairness in policies as they apply to future generations. As University of Virginia philosophy professor Loren Lomasky has written:

Theorists have devoted considerable attention to injustices committed across lines of race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and, especially, economic position. Far less attended are concerns of intergenerational fairness. That omission is serious. Measures that have done very well by the Baby Boomers are much less generous to their children and worse still for their grandchildren … [T]he single greatest unsolved problem of justice in the developed world today is transgenerational plunder.

In the last essay, I described how it was unfair for Senators long ago to enact a rule that forever after bound future Senators to a rule requiring a supermajority for the passage of legislation, a rule which itself could only be changed by a supermajority vote. Such a rule effectively denied voting power to successive Senators and made it more difficult for successive Senators to pass reforms, including reforms to automatic, ever-expanding mandatory spending programs. Professor Lomasky points out that a similar unfairness befalls successive generations of Americans as a result of those automatic, ever-expanding mandatory spending programs, writing:

Those who are bound by rules that they have had no part in formulating, deliberating, or endorsing [that is, the successive generations of Americans] have been disenfranchised as thoroughly as if they had been physically turned away from the polls. Their status is that of patients, not agents. They stand in a position of inferiority to the preceding generation, whose rules bind them but not vice versa … [L]aws drawn to benefit a current generational cohort at the expense of some later cohort that could not exercise a democratic voice in its enactment and that is mostly or entirely disabled from shedding the burdens imposed on it are of doubtful legitimacy. If I purchase lunch and have the bill sent to you, it is clear that you have been wronged. If we as a democratic polity vote ourselves free lunches and require our successors to pick up the tab decades from now, the wrongness is no less palpable … A saving grace of building up a substantial national debt is that there is no possibility the United States will inadvertently find itself insolvent. (One qualification: should Congress obdurately decline to legislate an increase in the debt limit, then all bets are off.) Whether amounting to billions, trillions, or even quadrillions, there is no limit to how many dollars the government can print. Of course, consequent inflation of the currency is a tax by another name, so one way or another debt places its hands on those not yet born.

To help remedy the intergenerational injustice he describes, Professor Lomasky outlines the following proposals that are worth consideration:

1. All proposed legislation or regulatory measures should be accompanied by a generational impact statement that spells out the nature and extent of any associated transgenerational impositions.

2. An alternative or supplement to a generational impact statement could be the establishment of a “generational ombudsman” charged with representing in all governmental decision-making bodies the interests of the young, including the unborn.

3. Long-term commitments such as pension contracts, the burden of which will substantially fall on taxpayers who had not been eligible to participate electorally when the commitment was originally undertaken, should be affirmed or nullified in subsequent referendums. (With the caveat that, to make sure the nullification isn’t in violation of rights, the original contract or legislation should include a proviso making clear its potential to be revised.)

● Congress could pass “joint budget resolutions” to bind Congress and the President to budget limits. As suggested by James Capretta:

Congress expresses its views on the budget in the congressional budget resolution (CBR). CBRs are not laws. Rather, they are concurrent resolutions, which means they are relevant only for Congress. Presidents are in no way bound by them and in fact have often denounced them as containing misplaced priorities. A possible, partial antidote for budgetary drift, rising mandatory spending, and neglect of long-term challenges might be found with a joint budget resolution (JBR). Unlike a CBR, a joint resolution must be agreed to by the president and therefore is a law. It thus has the potential to facilitate, and perhaps even pressure, the legislative and executive branches into coming to an agreement on key budgetary aggregates that would govern decisions by both branches later in the budget process. There are numerous ways to provide for the consideration of JBRs, but the most straightforward option would be to build on the current process. This can be accomplished by amending the current Budget Act rules to allow an optional JBR “spin-off” from any CBR agreed to by both the House and Senate. Congress would not have to pursue a JBR, but if it did so legislation would automatically get sent to the president upon adoption of a CBR, and the JBR would reflect the key budgetary aggregates: total discretionary spending, total mandatory spending, revenues, deficits, and debt. The president could then either approve or veto the legislation. If the president vetoed the JBR, the process would revert back to what is in place today under the Budget Act. Congress could proceed under the terms of the budget resolution, and engagement with the executive branch would be postponed until later in the year, when the spending and tax bills flowing from that budget were transmitted to the president. If, however, the president agreed to the JBR and signed it into law, the budget framework contained within it would have the force of law and both branches would be bound by it. A JBR covering the full budget would have the capacity to adjust the caps on discretionary spending, impose discipline on mandatory spending, and provide a target for revenues. This would ensure that Congress and the president truly engage in budgetary decision making. There would be clear trade-offs between the key budget categories, as well as projected deficit spending and debt. Congress and the president could choose to put more pressure on mandatory spending programs and thus perhaps ease the pressure on discretionary accounts, or vice versa. Although ideally a JBR should cover all aspects of federal budget policy, it would be possible to start with an interim step of adjustments just to the discretionary caps. The CBR would operate as it does today, except that, upon adoption of a conference report on a CBR, Congress would have the option of sending to the president a JBR providing for adjustments to the discretionary caps at the levels provided for in the CBR. This interim step would be important because it would empower the Budget Committees in the House and Senate; they would become the committees directly responsible for establishing these binding caps -- a first step toward a real budget process that would bind both the legislative and executive branches.

● Change House “blue slip” rules so the House Parliamentarian makes the first determination of whether or not a Senate bill violates the Origination Clause. In the House of Representatives, the blue slip rule refers to the rejection slip given to tax and spending bills sent to it by the Senate that did not originate in the House in the first place, under the House’s interpretation of the Origination Clause of the Constitution, which requires that “all bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.” The Supreme Court has largely gutted that provision by allowing the Senate to amend any House bill that raises any revenue at all, completely rewrite it to cover entirely new subject matter, and send it back to the House. Currently the House enforces its Origination Clause authority under the “blue slip” process under which the Majority or Minority Leader can offer a privileged resolution to send a Senate bill back when the House approves a resolution stating the Senate bill violated the Origination Clause by not originating it in the House. A possible reform might be a new House Rule that lets the House Parliamentarians, not the Membership, decide when the Senate has violated the Origination Clause in the first instance. The House precedents and practices have broadly construed its Origination Clause authority to include any “meaningful revenue proposal.” Perhaps a new House Rule could simply and flatly prohibit the House from voting on any bill for raising revenue that did not “meaningfully originate in the House.” The House could always overrule the House Parliamentarian’s ruling, but at least this new rule would require those objecting to the Parliamentarian’s ruling to take the step of overruling a decision of the House Parliamentarian rather than simply voting down, on partisan grounds, a resolution offered by the opposing party.

These proposals might seem “pie in the sky,” but if reforms along these lines aren’t adopted at some point soon, the next generation will get increasingly smaller slices of a much smaller pie, as previous generations eat even more of it.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6