As explored in previous essays, today federal mandatory entitlement spending continues automatically, without the need that it be revisited regularly by Congress. As a result, the inflation-adjusted U.S. debt burden per American is rising rapidly. That is, if it ever becomes necessary for the United States to pay off a substantial part of the federal debt because investors come to fear their loans won’t be paid back, individual federal taxpayers would be on the hook for an increasingly large amount of money.

Since the 1990’s until last year, here’s what the federal debt per capita has looked like:

Another way of looking at this is to see how, once you factor in what people will owe if the federal debt is paid back over time, people’s net worth drops. The following chart shows how per capita net worth, taking into account the future need to pay back federal debt, has fallen dramatically over the last several years. Seen this way, a family making just over $200,000 a year is really only making $62,000 a year, taking into account future deficits per person.

Taxpayers also have to pay interest in the debt. As we saw from a previously-linked video, in 2021, 14% of the $2.8 trillion in mandatory federal spending goes to service the interest on the national debt.

Payment of interest on the debt buys taxpayers no new goods or services at all. Interest on the debt is just the price charged by others to the U.S. government for the privilege of borrowing at all. And interest on the debt grows larger as debt grows larger. As described by James Capretta:

The new [CBO] report highlights how difficult it will be to get the federal budget back under control once debt crosses a certain threshold. As annual budget deficits accumulate, the government is required to make ever-growing interest payments on the total stock of debt. Further, as the government floods public markets with more debt, CBO projects interest rates will rise, pushing the government’s borrowing costs up still further. CBO assumes the annual interest rate on all federal debt will average 4.1 percent from 2039 to 2048, up from 3.1 percent from 2018 to 2028. Higher interest rates and more debt will push the government’s net interest payments up from 1.6 percent of GDP this year, to 3.2 percent of GDP in 2030, and to 6.3 percent in 2048. Put another way, in CBO’s forecast future workers would be required to pay taxes equal to 6.3 percent of GDP just to service the government’s accumulated debt, from which they would gain no direct benefit. It will be extremely difficult for politicians to impose the level of taxes necessary to finance the debt projected in CBO’s forecast and fully pay for all of the government’s current law programs and obligations. The danger is that interest payments will reach a point that will make it near impossible to reverse course and begin reducing the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio.

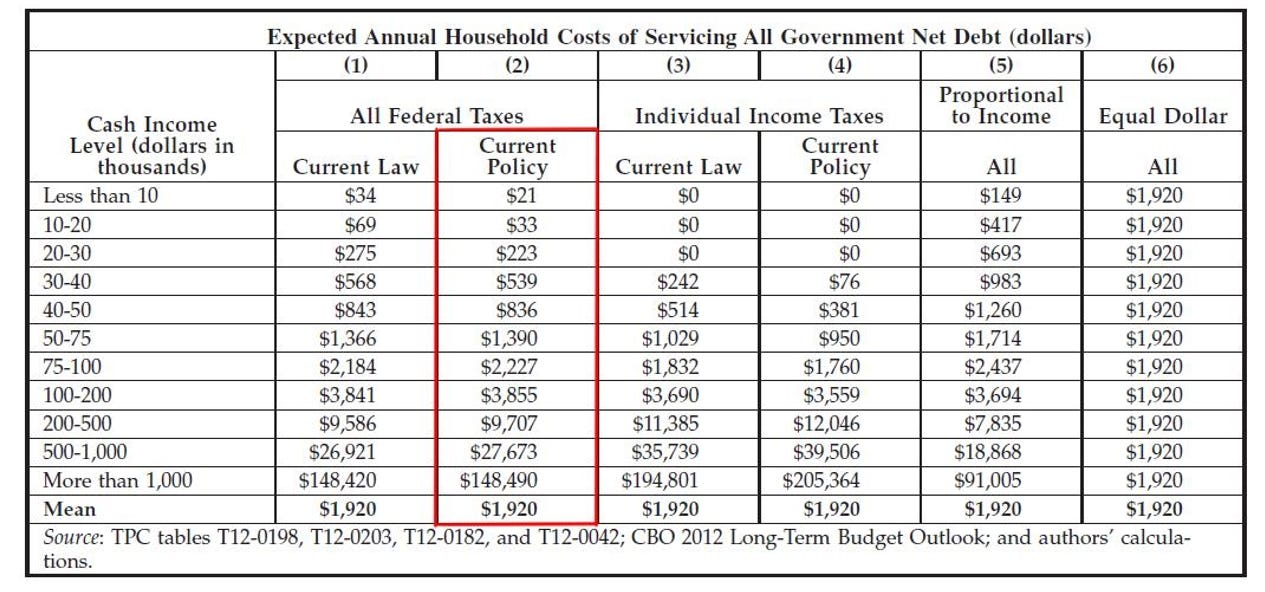

Under current policy, the annual costs to Americans by income group just to pay the annual interest on the current federal debt runs into the many thousands of dollars. As the chart below shows, a federal taxpayer who makes between $50,000 and $75,000 a year pays $1,390 in federal taxes just to pay interest on the debt.

While the Federal Reserve Board can keep interest rates low, in normal times interest rates will rise and the cost of entitlement-incurred debt will rise with them. Here’s what the Congressional Budget Office has said about the dangers of mounting net interest payments:

When interest rates rose to more normal levels, federal spending on interest payments would increase substantially. Moreover, because federal borrowing reduces national saving, the capital stock would be smaller and total wages would be lower than they would be if the debt was reduced. In addition, lawmakers would have less flexibility than they might ordinarily to use tax and spending policies to respond to unexpected challenges. Finally, such a large debt would increase the risk of a fiscal crisis, during which investors would lose so much confidence in the government’s ability to manage its budget that the government would be unable to borrow at affordable rates.

And elsewhere, CBO has said:

The increase in debt relative to the size of the economy, combined with an increase in marginal tax rates (the rates that would apply to an additional dollar of income), would reduce output and raise interest rates relative to the benchmark economic projections that CBO used in producing the extended baseline. Those economic differences would lead to lower federal revenues and higher interest payments. With those effects included, debt under the extended baseline would rise to 108 percent of GDP in 2038.

In August, 2018, the Congressional Budget Office issued a report providing estimates of what it would take for the U.S. government to keep federal debt below certain benchmarks in the coming years. It chose three separate potential levels at which policymakers might want to stabilize federal debt: 41 percent of GDP (the average level of debt over the past half century); 78 percent of GDP (the level at the end of fiscal year 2018); and 100 percent of GDP. The agency then calculated the amounts of sustained reduction in the government’s primary deficit that would be necessary over varying time periods to bring federal debt within the targeted levels. The results were that if policymakers wanted to bring federal debt back to 41 percent of GDP in fifteen years (by 2033), they would need to enact policies to cut spending and raise taxes by a combined 3.9 percentage points of GDP, and those policies would need to go into effect immediately and be sustained through 2033. In 2019, 3.9 percentage points of GDP is $830 billion. (To put that in perspective, the entire annual budget for the Medicare program was $776 billion in 2019.)

The total federal debt has grown dramatically over recent years as a percentage of the entire country’s gross domestic product. This growth in the federal debt occurred when Congress was controlled by both Republicans and Democrats, although the most significant increases in federal debt have occurred when Democrats controlled one or both houses of Congress.

Recent experience in advanced economies indicates that countries with debt above 80 percent of gross domestic product and persistent current-account deficits are vulnerable to doubts by lenders, which lead to higher sovereign interest rates. Researchers studying this issue concluded that:

Recent sovereign debt crises among advanced economies have provided a rich data base for empirical analysis of the sensitivity of sovereign yields to debt levels and other aspects of fiscal risk. Our empirical work used both econometric analysis and event studies, and suggests that countries with debt above 80% of GDP and persistent current-account deficits are vulnerable to a rapid fiscal deterioration as a result of these tipping-point dynamics.

When a nation’s debt grows to around 80% of GDP or more, the added debt tends to begin to cut into annual economic growth, according to the World Bank, and at the end of the second quarter of 2021, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ration was 125%.

In July, 2021, even the historically growth-optimistic Congressional Budget Office released its Updated Budget and Economic Outlook for the next decade, projecting the national debt to reach a new record of 106.4 percent of GDP by 2031.

National debt cannot increase forever without incurring catastrophic results. As C. Eugene Steuerle writes in his book Dead Men Ruling:

Of course, nothing like [unending and perpetually increasing debt] would ever come to pass. At some point before debt ever reached such hypothetically projected levels, we would find ourselves without the lenders to continue to feed our fiscal appetite. That is because, as former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke warned almost throughout his tenure, lenders do not continue to lend to borrowers who make no effort to address their debt problems. That is true for a family that wants to borrow more from a local bank, or a country that wants to borrow more from its residents or its lenders overseas. Moreover, even before reaching that borrowing end point, the nation could face an economic crisis as lenders begin to lose confidence and, as a result, demand higher rates of return on their investments -- that is, higher interest rates. Their loss of confidence could send the dollar plummeting on global markets, which would send inflation soaring and force even higher interest rates, which would cause the dollar to fall even further in a vicious cycle. No one knows when the day of reckoning may arrive -- the day when lenders might refuse to lend us any more money, or the day when they get nervous enough to demand a higher rate of return on their lending, or when higher interest rates cascade into a cycle of a plummeting dollar, soaring inflation, and a weakened economy.

Even without a day of reckoning or crisis, rising debt poses huge limitations on what the government, and, more broadly, the economy can do. Rising debt levels imply that ever- larger shares of our income and our government spending will go to pay interest on that debt, much of which today goes to foreign governments, many of which are not friendly to us. Rising interest rates or a lack of economic confidence tends to reduce private investment, which in turn reduces growth rates even in absence of outright recession or depression.

Many claim that the U.S. will never face a debt reckoning because, no matter how bad the fiscal situation becomes in the United States, investors won’t be able to turn anywhere else for investments because other countries will be in even worse fiscal shape. But in 2012 the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development published a report assessing the fiscal consolidation requirements for its member countries. According to the OECD assessment, the U.S. is an outlier (in a bad way) in terms of the amount of deficit reduction that would be necessary to keep debt under control. For the U.S. to reduce its debt level down to 50 percent of GDP by 2050 would require sustained deficit reduction of 6.9 percentage points of GDP beginning immediately. The only other country expected to need more sustained deficit reduction over that period is Japan (9.6 percentage points of GDP).

Most of the other countries require an average of about 3 GDP-percentage points of deficit reduction over the coming decades to reach the debt goal of 50 percent of GDP, as many other countries are in better positions than the U.S. That’s because some other countries have enacted deep cuts in spending to limit their debt increases and other countries, such as Sweden, have enacted significant changes in their state-sponsored pension systems to reduce their long-term obligations.

What about the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank that’s authorized to set interest rates? Could the Federal Reserve always prevent a significant fiscal crisis? Well, just like the CBO, the Federal Reserve’s monetary easing policies have been accompanied by economic projections that have consistently proven to be significantly wrong.

In addition, one researcher has presented evidence that monetary policy is becoming increasingly less effective today in reducing unemployment because the Federal Reserve acts by lowering interest rates. But today, many countries, including the United States, have fewer young people, and it’s young people who tend to borrow most as they use credit to smooth out what they can consume over the course of their lives. In countries with increasingly more older people (like the United States), fewer people use credit products, and this researcher found that a one-percentage-point increase in the share of the population that is elderly (the “old-age dependency ratio”) lessens the effectiveness of monetary policy in affecting inflation by 0.1 percentage points and unemployment by 0.35 percentage points.

The next essay will explore the relative size of health care entitlements, other potential federal taxpayer liabilities, and a preview of longer-term trends.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6