There’s always a lot of talk in politics about government spending, perhaps now even more so. The numbers involved with the federal budget have become so staggeringly large that it’s often difficult to get any real sense of their significance beyond a general sense of their sheer size. So in the next series of essays, I’ll be presenting some interesting ways others have described the scope of the problems associated with huge federal debt, to help people get a better understanding of it.

These particular essays will just examine the scope of federal spending and its implications, and not whether any particular spending is “worth it” or not. (Although I will note here that former officials in the administrations of both Barack Obama (Peter Orszag) and George W. Bush (John Bridgeland) have jointly concluded that “less than $1 out of every $100 of government spending is backed by even the most basic evidence that the money is being spent wisely.”) But for now, let’s just focus on the sheer size of the spending.

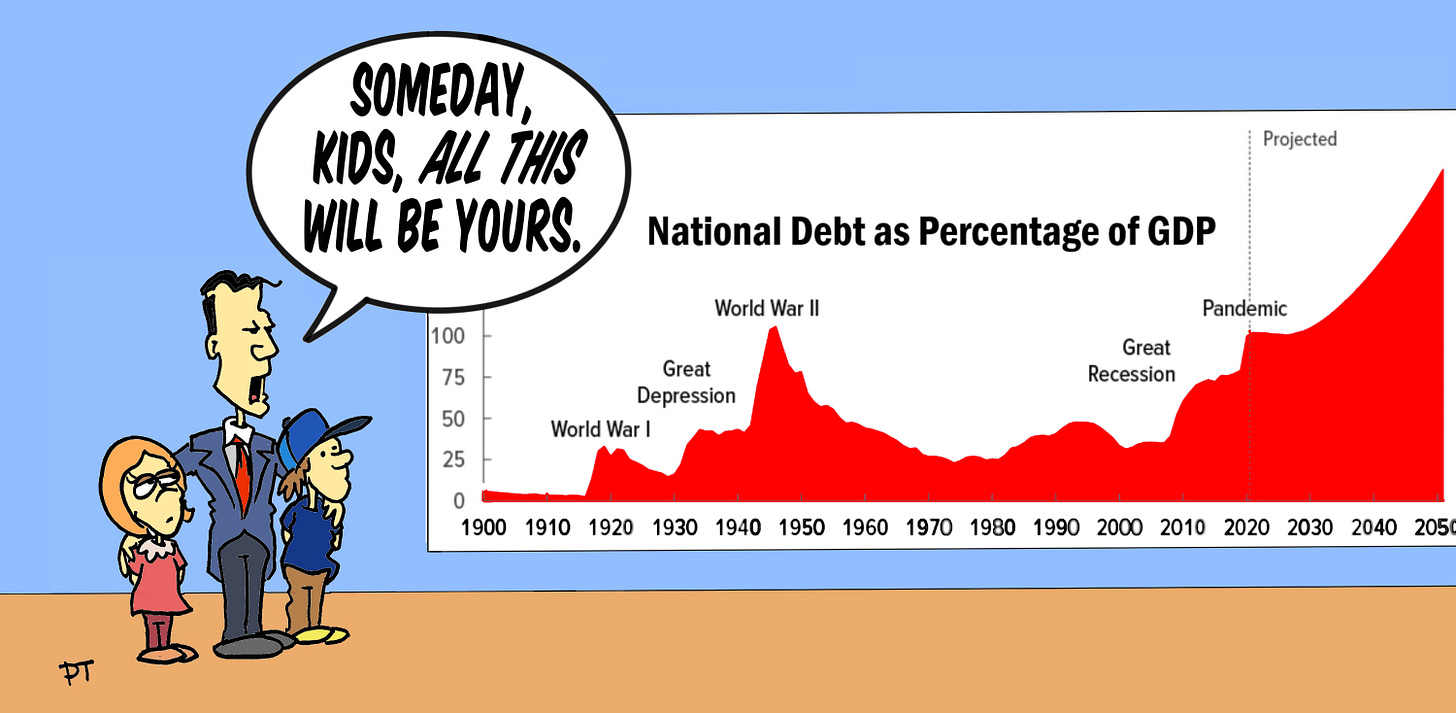

Let’s start with some history. The Founders originally understood Congress to have only limited, enumerated legislative powers. As the former historian of the House of Representatives, Robert V. Remini, has written in his book “The House: The History of the House of Representatives”:

The Framers of the Constitution were absolutely committed to the belief that a representative body, accountable to its constituents, was the surest means of protecting liberty and individual rights. So anxious were they to affirm legislative supremacy in the new government that they failed to flesh out the executive and judicial departments [in the Constitution], leaving that task to Congress, and thereby assuring that the legislature would retain control of the structure and authority of both those branches.

And within that system of legislative supremacy, the House of Representatives was to serve a unique role. Alone among all federal institutions, the House has consisted solely of those duly-elected by the People throughout its history.

What have become known as “The Federalist Papers” are a series of essays written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay that put forth arguments that the states should ratify the Constitution at our Founding. In Federalist No. 39, James Madison wrote, “The House of Representatives … is elected immediately by the great body of the people.” As such, “The House of Representatives will derive its powers from the people of America.” In Federalist No. 52, Madison wrote, “As it is essential to liberty that the government in general should have a common interest with the people, so it is particularly essential that the [House] should have an immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people. Frequent elections are unquestionably the only policy by which this dependence and sympathy can be effectually secured.” And again, in Federalist No. 57, Madison wrote:

All these securities, however, would be found very insufficient without the restraint of frequent elections. Hence, in the fourth place, the House of Representatives is so constituted as to support in the members an habitual recollection of their dependence on the people. Before the sentiments impressed on their minds by the mode of their elevation can be effaced by the exercise of power, they will be compelled to anticipate the moment when their power is to cease, when their exercise of it is to be reviewed, and when they must descend to the level from which they were raised; there forever to remain unless a faithful discharge of their trust shall have established their title to a renewal of it … If it be asked, what is to restrain the House of Representatives from making legal discriminations in favor of themselves and a particular class of the society? I answer: the genius of the whole system; the nature of just and constitutional laws; and above all, the vigilant and manly spirit which actuates the people of America -- a spirit which nourishes freedom, and in return is nourished by it.

Back then, the need for Congress to heed the desires of the People manifested itself in the federal budget process. When the first Congress in 1789 considered the law creating the Treasury Department in the executive branch, the bill as originally introduced authorized the Secretary of the Treasury “to devise and report plans for the improvement and management of the revenue.” But it was feared that even giving the Secretary of the Treasury the modest power to “report plans” implied too much authority for the executive branch, and so the bill was amended to authorize the Secretary only to “prepare plans” regarding the management of revenue. (See Davis Rich Dewey, Early Financial History of the United States (1934) at 85-86.) The amended bill also specifically required the Secretary “to make report, and give information to either branch of the legislature, in person or in writing (as he may be required), respecting all matters referred to him by the Senate or House of Representatives, or which shall appertain to his office.” It thus allowed Congress to keep a close eye on federal spending and to request financial information directly from the Treasury Secretary, bypassing the President, and it made clear that Congress, and not the president, was the ultimate authority on budget issues. (See Davis Rich Dewey, Early Financial History of the United States (1934) at 87.)

In the early days of the republic, things were supposed to work pretty simply: if the federal government wanted to fund a project, like building a post road or a lighthouse, it allocated a specific amount of money for the project. If that amount of money was used up, Congress would then have to approve the spending of a specific amount of additional money before the project could be completed. This allowed the People to step in and make their views know about federal spending during regular elections before too much money was spent on something the People might come to see as a mistake. As Davis Rich Dewey writes, “In theory the great bulk of appropriations are annual in nature in accordance with the principle of popular government that the people shall have a firm grip on its purse.” Although large expenditures could be made outside the annual appropriations period, they were still made “by permanent specific appropriations, as for river and harbors, fortifications and public buildings, which remain available until the money is spent.” (Dewey, at 560-61 (emphasis added).)

As Urban Institute scholar C. Eugene Steuerle has written in his excellent book “Dead Men Ruling: How to Restore Fiscal Freedom and Rescue Our Future”:

For most of American history -- from the founding of the republic to at least the end of World War II -- the reality of governing in Washington reflected the truism, “To govern is to choose.” Each year, our elected leaders decided which programs to fund and how to finance them. They set new priorities based on the challenges at hand, be they war or recession, poverty or hunger, civil strife or economic injustice. Despite rancorous debates, our leaders normally had much more fiscal freedom -- the leeway to set priorities, shift direction, and respond to new challenges -- than they do today. Why? Because the president and Congress created and funded programs mostly on a year-to-year basis, extending them only after first considering other ways to use available revenues.

But in the 1930’s, things began to change:

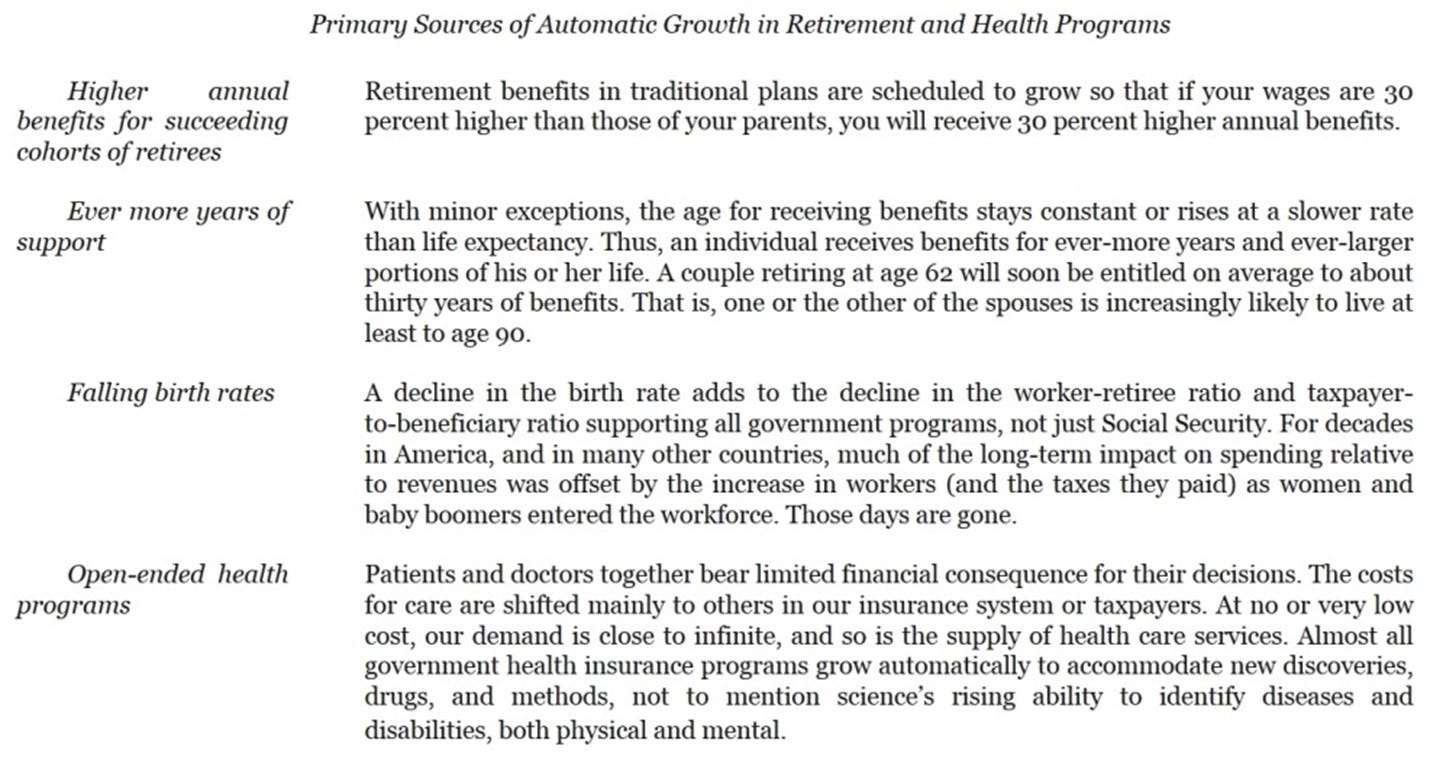

Let us begin with the basics. Federal spending comes in two basic varieties: discretionary and mandatory. For discretionary spending, the president and Congress decide each year which programs to fund, which new ones to create, and which old ones to kill. To do so, they enact twelve appropriations bills that, today, fund the defense budget and a wide range of domestic programs in many areas -- from education to environmental protection, from biomedical research to food safety, from transportation to border security, and so on. Congress must vote to fund most of these programs every year. For mandatory spending, the president and Congress create programs (mainly “entitlements”) that continue automatically from year to year, unless policymakers enact laws in later years to change them. These entitlements have increasingly dominated federal spending. President Franklin Roosevelt worked with Congress to create Social Security in 1935, the first major spending entitlement, while President Lyndon Johnson, who sought to expand the New Deal into the Great Society, worked with Congress to create Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. As they created these and other entitlement programs over the years -- Food Stamps, unemployment insurance, the Earned Income Tax Credit, disability insurance, civilian and military retirement programs, Supplemental Security Income, and others -- policymakers expanded many that were already in place. They also designed a number of them, particularly in retirement and health, to grow automatically forever by annually providing more generous benefits to more eligible people. To top it off, these automatic growth rates, particularly in retirement and health programs, were sometimes set at levels above the growth rate in people’s private incomes and the economy itself.

As entitlements and tax expenditures grow regardless of changing societal needs, they require more spending, drain revenues, and reduce fiscal freedom. Eventually, the prospect of new and growing future deficits arises even in the absence of any new congressional action. At this fiscal turning point, the decision of policymakers simply to let mandatory spending grow automatically typically outweighs all of their deficit-cutting actions on the discretionary side.

What causes all this growth? Basically, retirement programs automatically spend ever-larger shares of our GDP due to (1) benefits that increase automatically as wages increase, (2) ever-more years of support as people live longer, and (3) the decline in taxpayers relative to beneficiaries when birth rates fall. In health care, the growth largely comes from some of the same demographic pressures and from the cost pressures that derive from a key feature of most health insurance: allowing patients and doctors to decide what everyone else will pay.

The bottom line, then, is this: throughout the nation’s history, only recently has spending been scheduled to rise faster than revenues on a permanent basis. Today, unlike before, any new spending increase or tax cut -- including those that the nation might consider to address an economic slowdown -- cannot be offset down the road by future expected revenue growth. This simple historical change in the structure of fiscal policy drives much of the fiscal anguish and confusion that permeates all or almost all developed nations. Where policymakers of the past could achieve budget balance simply by enacting few or no increases in discretionary spending for a while, or in a few cases (mainly after war) cutting discretionary spending, such a strategy would prove futile in today’s fiscal context. Now, the reverse is true. Built-in growth in spending will exceed the growth in revenue forever -- or until the economy collapses. Eventually, with revenues completely allotted to finance fast-growing entitlements (as they were temporarily for the first time in 2009), Congress will have to finance any dollar of discretionary spending by borrowing, often from abroad.

So starting in the 1930’s, Congress established spending programs that mandate the continuation of federal funding streams without the need for regular review by Congress. The laws that established those mandatory spending programs authorize unlimited spending on those programs until Congress enacts new laws overriding the old ones. So today, Congress can simply sit back and do nothing, and in sitting back and doing nothing allow unlimited mandatory spending to continue.

The Steuerle-Roeper Index

Steuerle has developed a way of measuring the extent to which past and future projected revenues are already claimed by the permanent entitlement programs that are now in place, including interest payments on the federal debt. By that measure, we have already reached the point at which each session of Congress will begin without there being any wiggle-room for spending any more money for anything without, at the same time, enlarging the federal debt. (The zero point on the chart below indicates where expected federal revenues equal mandatory spending that is already committed in any given year.)

As Steuerle describes this chart:

The U.S. index fell into negative territory for the first time ever in 2009 -- meaning that every dollar of revenue had been committed before the new Congress walked through the Capitol doors. Revenues for the first time in U.S. history fell short of the built-in spending of permanent programs -- and it will return to negative territory as soon as a decade from now if the president and Congress do not change current entitlement and tax policies [and they haven’t]. Even efforts, such as those scheduled in much of current law, to reduce annual non-entitlement spending toward zero -- thus, ending most education, transportation, housing, defense, and most other general government programs -- will do little to alter the downward path of the index other than reduce interest costs temporarily. That means that future generations will have no additional revenues to finance their own new priorities, and they will have to raise taxes or cut other spending just to finance the expected growth in existing programs.

With many entitlement programs growing automatically, the baby boomers starting to retire in ever-increasing numbers, and federal revenues falling further behind, all future revenues will again be committed (actually, overcommitted) to meet the promises that previous presidents and Congresses have made. Which constitutional framer would have thought that, by the turn of the twenty-first century, lawmakers had already attempted to determine the budget for 2030, 2070, 2100, and even beyond? In essence, dead and retired policymakers put America on a budget path in which spending will grow faster than any conceivable growth in revenues -- even if the president and Congress never create any other spending program.

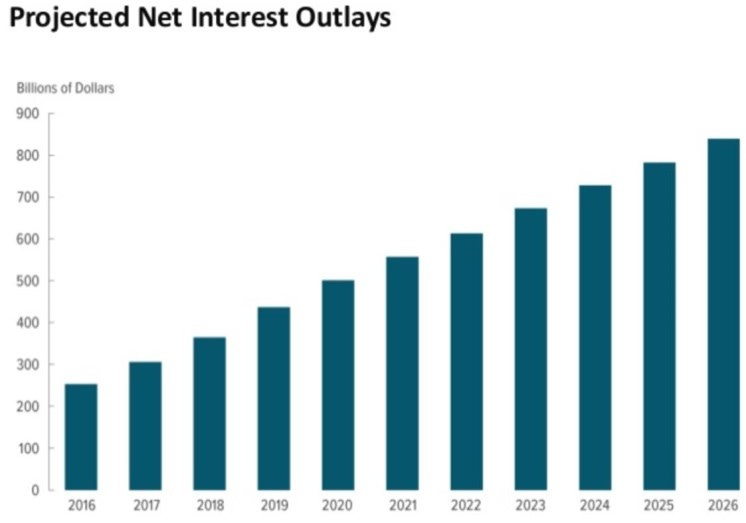

Even before the massive increase in federal spending during the last couple of years, it was estimated that by 2026, the Fiscal Democracy Index will fall to 1.7, absent reforms, leaving just a sliver of incoming annual revenue to pay for everything the federal government does other than mandatory entitlement spending, such as paying for national defense, federal policing, natural disasters, basic research, and everything else. And with that more recent increased federal spending, we’re now left with future Members of Congress’ facing the following situation: beginning on the day they’re sworn in, every penny of expected federal revenue for the coming year will have already been spent by operation of statutorily mandated spending dictated by laws enacted years or decades earlier. Therefore, Members of Congress today face a situation in which every proposal for new spending on anything must necessarily increase the national debt. (Some may say that increasing federal taxes is a solution, but as we’ll see in future essays, increasing taxes won’t work because there will never be enough money in private hands to cover the debt while allowing society to maintain any remotely acceptable standard of living.)

Even back in 2016, the Congressional Budget Office had shown how, over the next ten years, the costs of Social Security, major health care programs, and net interest payments on the debt will dominate the federal budget, leaving only 12 percent of revenues to pay for all other federal programs.

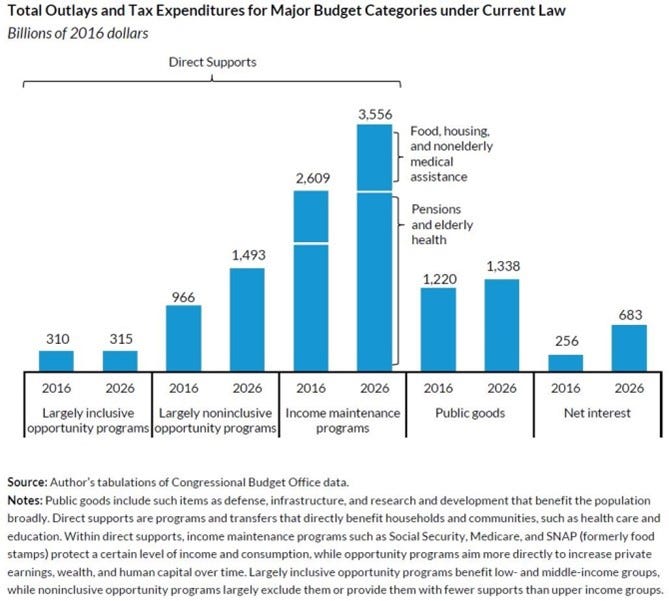

As Eugene Steuerle has pointed out, “the few [federal] programs that attempt to promote opportunity, such as work incentives and education, are scheduled to decline in the future and take a smaller share of available federal government resources,” whereas “[i]ncome maintenance programs, driven chiefly by health care and retiree benefits, [will] dominate the budget,” and “many [of such programs] have embedded in them negative work incentives through sometimes steep, sometimes modest, means testing or through signaling households to drop out of the labor force in what might easily be considered late-middle age as measured by remaining life expectancy and good health.”

What that means is that many mandatory entitlement programs that stagnate opportunity (by giving people excessive cash and services that discourage them from working) have crowded out potential future funding for programs that encourage work and education, which would increase opportunity. We’ll explore the consequences of this more in the next essay.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6