Skin in the Game – Part 2

From no skin in the game to no DNA in the game.

In a previous essay I quoted University of Virginia philosophy professor Loren Lomasky, who’s written:

Theorists have devoted considerable attention to injustices committed across lines of race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and, especially, economic position. Far less attended are concerns of intergenerational fairness. That omission is serious. Measures that have done very well by the Baby Boomers are much less generous to their children and worse still for their grandchildren … [T]he single greatest unsolved problem of justice in the developed world today is transgenerational plunder.

Why is that?

I suspect it has something to do with the fact that only people with children actually have a version of “real-life skin in the game,” in the form of DNA. While people with kids and people without kids can all be responsible, only people with kids have a special connection to the well-being of successive generations: the double helix. And with that special connection comes a stronger incentive to act in accordance with that special concern for the well-being of future generations, generations that will include one’s own children if you have them.

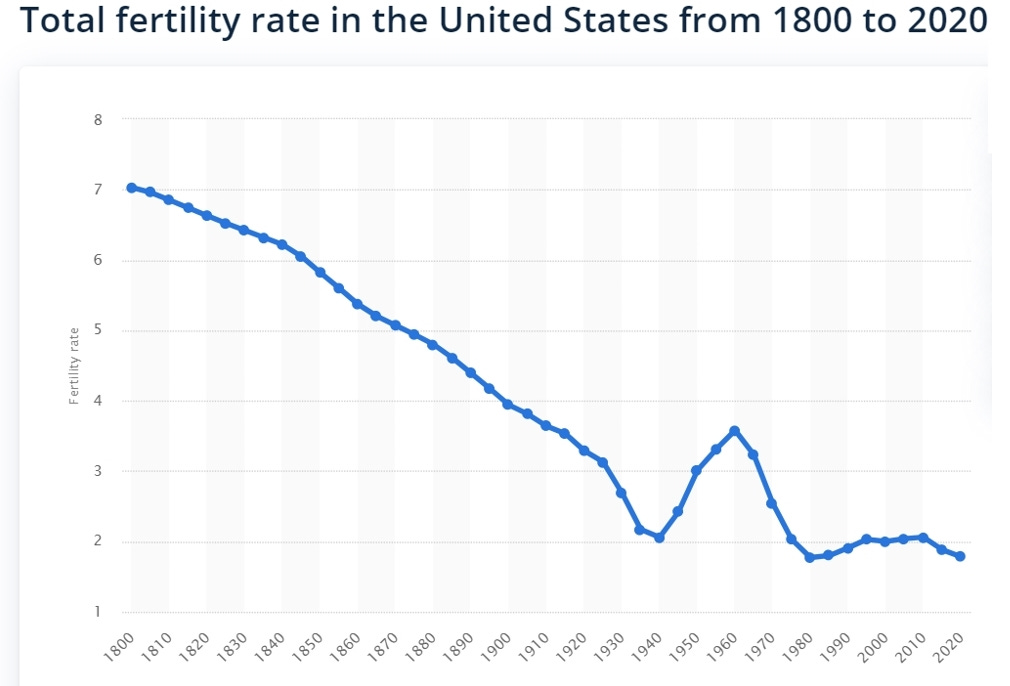

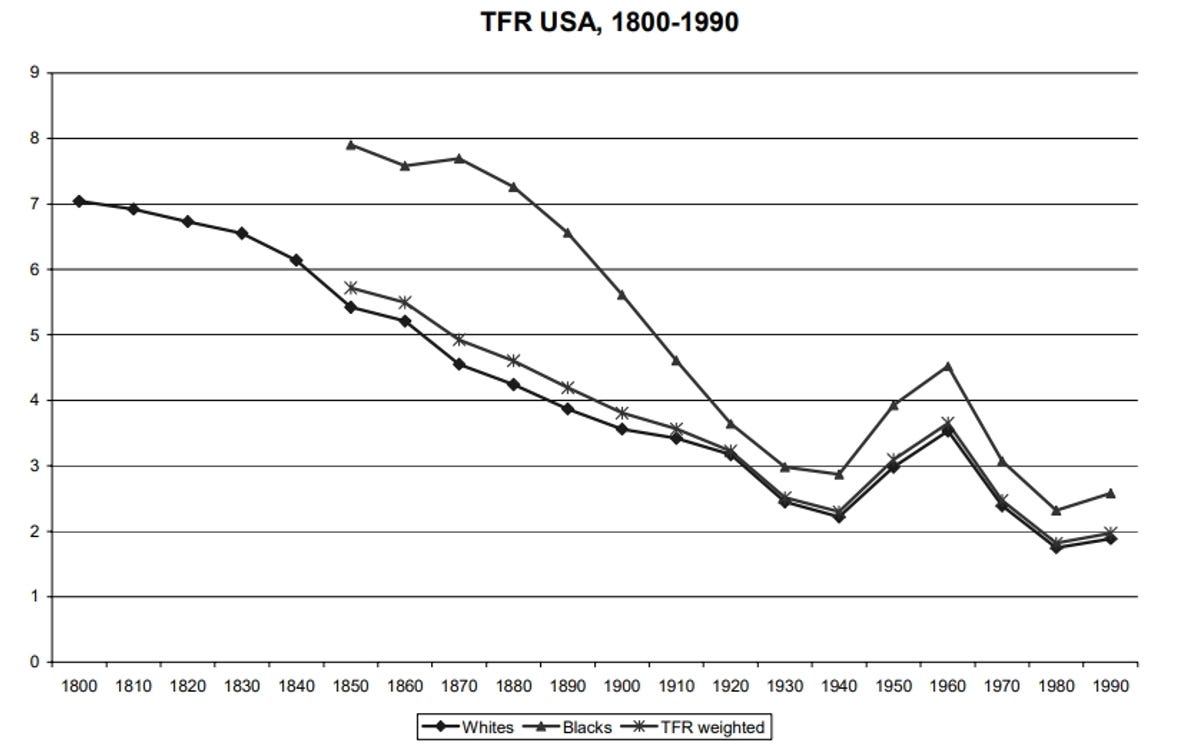

And fertility rates in the United States have been declining. Today, we’ve reached a historic low.

As Joel Kotkin summarizes:

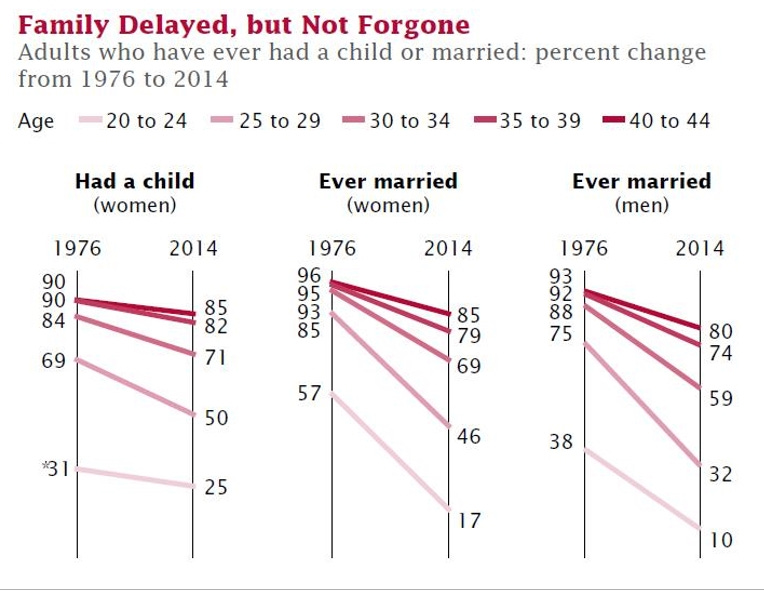

In the United States, more than a quarter of households in 2013 were single-person households. In urban areas like Manhattan, that figure is estimated at nearly half. In 2018, a record 35 per cent of Americans aged 25 to 50, which is 39 million people, had never been married, according to a new Institute for Family Studies (IFS) analysis of US Census data. The share was only nine per cent in 1970.

That means America has fewer citizens who have kids. And that has a large economic impact along a variety of dimensions, far beyond contributing to the demise of the Toys R Us toy store chain. Oddly, academic economists generally ignore the beneficial economic effects of the “social issue” of birth rates, even when higher birth rates have the same “productivity” effects as the “non-social issue” subjects academic economists tend to prefer to discuss (such as factory output or increased immigration). Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry has written on how economists tend to ignore phenomena that might be characterized as “social issues” even when those phenomena yield the same sort of positive results as other “non-social issues,” in which case one would think both phenomena should be encouraged. He uses the following example:

Most economists think economic growth is pretty important, and spend lots of time thinking about how to increase economic growth and making proposals for increasing economic growth. What is economic growth? Economic growth is the addition of productivity growth and population growth. To say this is extremely bland--it's just an accounting definition. But I point this out because economists’ thinking and proposals almost exclusively focus on productivity growth and completely ignore population growth. Economists have countless ideas on how government might do things to improve productivity growth, but the idea of using government to improve population growth is, quite simply, taboo. If economists are biased by a perspective which finds the idea of natalist policy squeamish, this makes perfect sense. If economists are dispassionate analysts, it doesn’t … Economists are aware of the definition of economic growth. That they don't take it to their natural conclusion is strong evidence of bias. Another bet: if you took my random ten economists and asked them to list the top 5 reasons why Japan has experienced moribund economic growth over the past 20 years, “shrinking/aging population” would be on most of the lists. If you then asked them to list the top 5 things an average advanced economy should consider in order to increase growth over the next 20 years, “increase population growth” would not be on the list, even though to say that increasing population growth would lead ceteris paribus to increased economic growth is a tautology … Usually if economists acknowledge the population growth problem, their preferred solution is to increase immigration--which aligns perfectly well with the “cosmopolitan perspective” [economist Tyler] Cowen praises … The normal argument for immigration is that more people will allow for more specialization, which should raise productivity as people focus on the things they’re best at and learn from each other. That this is also an argument for increasing the birth rate seems not to occur.

Whether or not academic economists pay much attention to national birth rates, those birth rates have dramatic impacts on national policy. In May, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that U.S. births declined 4% last year [in 2020] — about double the average annual rate of decline between 2014 and 2019 — and hit another record low. The total fertility rate, or the average number of times a woman will give birth in her lifetime, declined to a record low of 1,637.5 births per 1,000 women, which is much lower than the population “replacement” rate (the level of fertility at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next) which is about 2,100 births.

Census data also shows that people are waiting much longer to get married or have a child, if they have children at all.

As Lyman Stone reports:

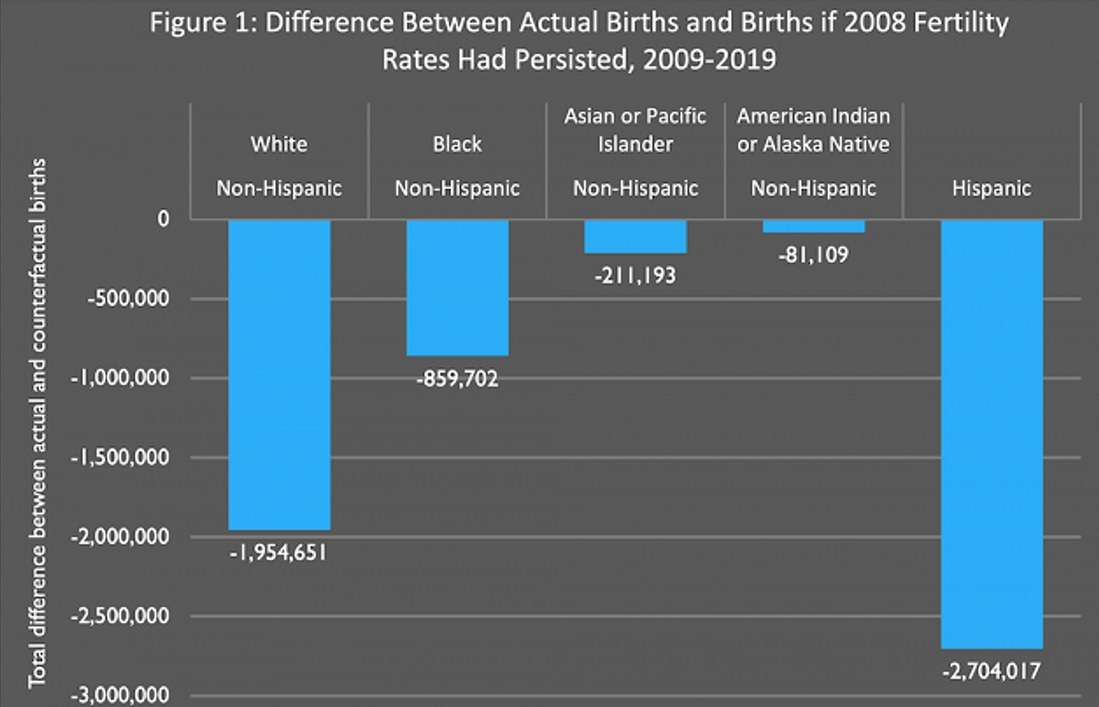

Fertility rates have fallen around the world over the last decade—even in countries with generous social welfare states, which experts had long expected to be holdouts in the face of fertility declines. But while demographers often talk about this change in terms of “fertility rates” or “births per woman,” another way to tally the total is in terms of missing births. That is, if the population of women who might have kids changed the way it did over the last decade, and if fertility rates had remained at their 2008 levels (the last time we had replacement-rate fertility in America), how many more babies would have been born? The answer is 5.8 million babies. Since births in the U.S. actually tend to run around 4 million per year, that’s almost like saying nobody had a baby for a year and a half. Figure 1 below shows the difference between the number of babies actually born to moms of each major racial or ethnic group tracked by the CDC from 2009-2019, and the number that would have been born, had 2008 fertility rates remained stable but underlying population totals changed in the same way.

Lower fertility rates, overlayed on top of a welfare entitlement system in which a greater proportion of both seniors and younger people are receiving more and more government benefits, means parents today are raising children who will have to pay a much larger share of the taxes needed to sustain that welfare entitlement system (which, as explained in previous essays, is unsustainable in the long run). Economist Robert Stein has suggested that for the federal government to be neutral with respect to the decision to have children by implementing policies that neither discourage nor encourage children, the child tax credit would have to be expanded fourfold or more. As he writes:

There are, of course, already some modest tax benefits attached to having children. Combining the impact of the $1,000 per-child tax credit with 15% of this year's dependent exemption of $3,650 (15% being the income-tax rate paid by most middle-class parents), it turns out that having a child today reduces the typical household’s annual tax burden by a total of about $1,550. But considering both the cost and the value of raising children, $1,550 is much too low. The exact cost of raising a child is notoriously difficult to estimate, given disparities in spending at different income levels — not to mention the countless unquantifiable factors involved. But if we take the commonly cited Department of Agriculture figure of $13,000 per child per year through age 17 (a figure that does not even account for college-education costs) — and the fact that Social Security and Medicare will absorb about 25% of the labor income of a child born today — we would find that sharing the direct financial costs of raising children to the same extent that the benefits of their future labor income will be shared would require reducing the annual tax bill of parents by $3,250 per child (25% of $13,000). Another way of looking at the issue is to consider that the present value of future Social Security and Medicare contributions for a typical worker born today is about $150,000. Rewarding parents for creating these future contributions suggests annual tax relief of about $8,500 per child. To correct for this inadequate treatment of households with children, the existing dependent exemption for children, the child credit, the child-care credit, and the adoption credit should be replaced with one new $4,000 credit per child that can be used to offset both income and payroll taxes. (This amount is set much closer to the $3,250 figure than the $8,500 one mostly to reduce the plan’s negative impact on federal revenue.) The new child credit would accomplish several significant policy goals. First, it would offset the anti-parenting bias created by Social Security and Medicare. Second, the credit would help simplify the tax code by getting rid of other exemptions and credits that apply to children. Third, and very important for many families, it would end the bias against families with a stay-at-home parent now caused by the child-care credit (which applies only if both parents are working for pay). And finally, it would reduce effective marginal tax rates for many middle-class families.

Bipartisan scholars at the liberal Brookings Institution agree, noting that expanding the child tax credit would signal to low- and middle-class families “that the nation values the parental investments they are making in the next generation, who—it should be noted—will be helping cover the cost of Social Security and Medicare in the near future.”

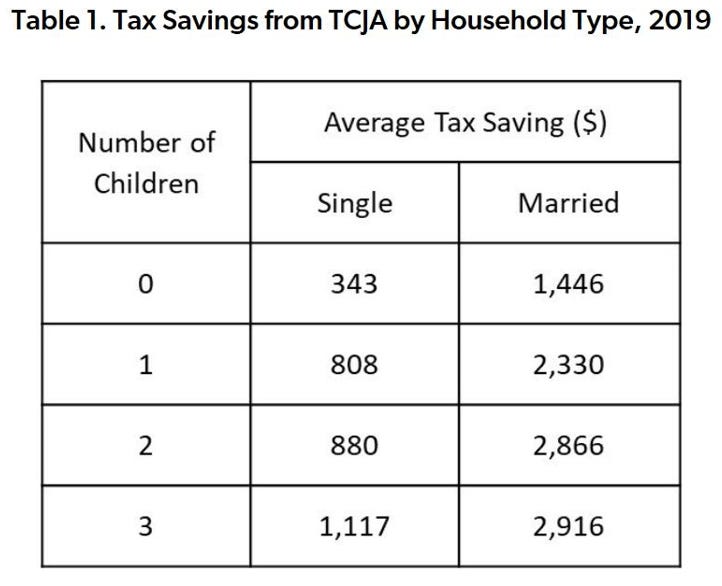

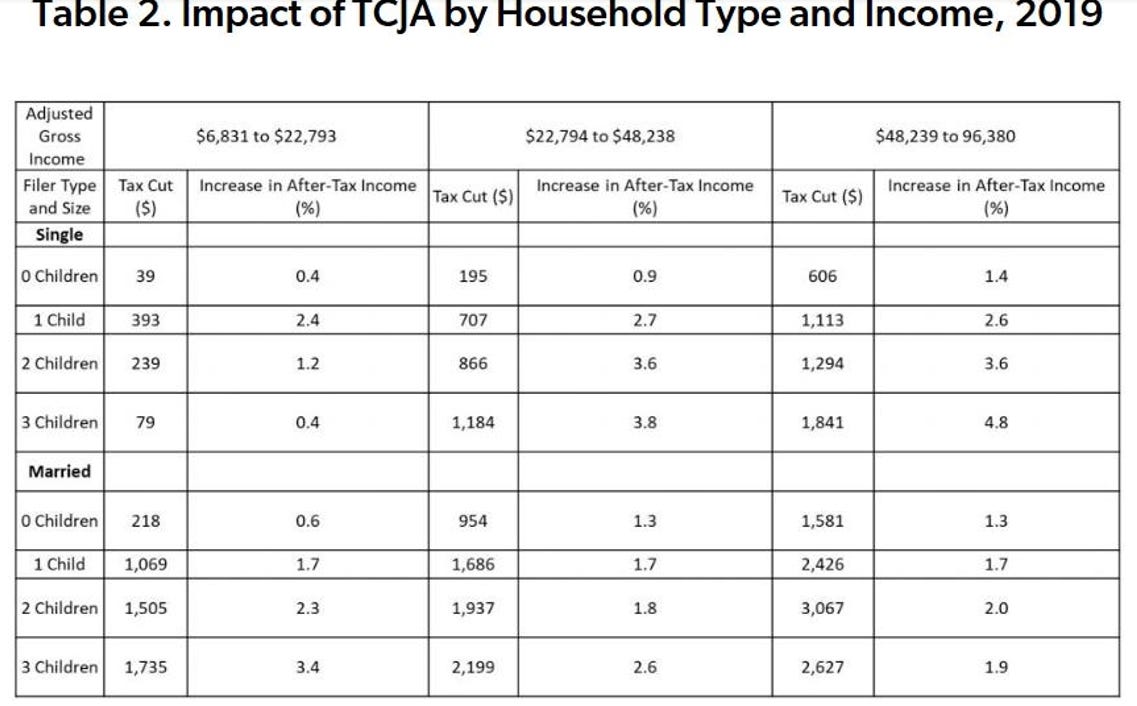

As it turns out, under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the average tax cut provided was larger for taxpayers with children, and the tax cut increases as the number of children increases. The average tax cut is also larger for married households than for unmarried filers. Single childless taxpayers receive an average tax cut of $343, while married childless taxpayers receive an average tax cut of $1,446. Single taxpayers with one child receive, on average, a tax cut of $808, and married filers with one child receive an average tax cut of $2,330.

The below table provides more details on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017’s effects by reporting the average savings among those in the second, third, and fourth income quintiles (the middle class). The table reports the average tax cut and change in after-tax income across eight taxpayer scenarios (single or married with zero, one, two, or three children).

Of course, expanding child tax credits or lowering taxes without reducing entitlement spending will require the government to get that lost tax money elsewhere. And the “anti-parenting bias created by Social Security and Medicare” to which Stein refers is interesting on its own terms. That bias is a well-studied phenomenon in which the Social Security system itself has helped lead to a drop in the birth rate, as people have come to increasingly rely on the government, rather than their own children, to help provide for them in their retirement. Several Federal Reserve economists, in their Journal of Demographic Economics article entitled “Fertility and Social Security,” conclude:

A number of authors have suggested that the welfare state, and the public pension system in particular, might be an important factor behind the drop in fertility to the bare (or even below) replacement levels most Western countries are experiencing. Controlling for infant mortality, income level, and female labor force participation, almost all regression exercises, including ours, point to a strong negative correlation between the size of the Social Security system and the Total Fertility Rate [“TFR” in the chart below], both across countries and over time. In particular, we observe the following: fertility rates were much higher in the United States and Europe around 1950, when both groups of countries had a much smaller pension system than they do; since the late 1970s fertility rates have been persistently lower in Europe than in the United States, and the former countries have a substantially larger pension system than the latter.

In the next essay, we’ll look at some of the policy consequences of the fertility bust.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5