In my city of Alexandria, Virginia, anyone can watch archived videos of local school board meetings. I’ve watched a lot of them. At these meetings, a large chunk of the time is spent watching administrators read verbatim from PowerPoint presentations on this or that subject, and as far as I can tell there’s essentially no discussion of what should matter most to school boards, namely how student performance can be improved and measured by objective standards.

The extent of that problem is made clear in Great on Their Behalf: Why School Boards Fail, How Yours Can Become Effective, a book by A.J. Crabill, a former school board member and student advocate. Crabill writes:

The lack of parental confidence in public education, at least in some quarters, emerges in part from the fact that the public so rarely sees its boards of education talking about whether the children are learning what they need to be successful in life. I suspect that both conservatives and liberals could agree on this … Most school boards generally behave professionally: in a manner that allows the operations of the school system to be conducted. But professional behavior is not the same as effective behavior: behavior that creates the conditions for improvements in student outcomes. Instead, it is common that school boards are professionally ineffective: conducting the adult inputs- focused operations of the school system but not inspiring improvements in instructional quality that drive increases in what students know and are able to do. It is common that school boards are not student- outcomes-focused … [M]ost states and state laws focus on school boards being professional, on managing the adult inputs, but almost none of them focus on school boards being effective, on improving the student outcomes.

Crabill describes some human tendencies that prevent school boards from focusing on student achievement:

There are many ways board members indulge in pretending rather than confronting the harmful reality of our actions: [such as] Pretending that the welfare of students is more important to me than my own reputation and livelihood; [and] Pretending I know what the students need when I have not rigorously investigated this.

This insular mindset among school board members is fostered by an understanding that they need to work primarily if not exclusively through the school superintendent (a high-level bureaucrat) in formulating school policies. As a result, school board members are largely existing in a bubble that isolates them from on-the-ground understandings of classroom dynamics.

On June 11, 2023, a couple of local school board members held a question and answer session at a nearby park. One person in the audience, whose sentiments were reaffirmed by many others, pointed out how the school administration submits written materials for the board to consider at the eleventh hour, with predictable results: “None of you [school board members] had the time to read it [a report submitted late to the board]. If it were me, I would have looked at them and said you gave this to me last night. It’s eighty pages. This is an important conversation. Come back to me [later] now that I’ve looked at it and I can properly ask you questions. Instead, I hear these questions [from school board members] that are surface level, that are agreeable, that are go-along to get-along, and it gets passed and everyone accepts it … There’s no accountability.”

Even when school boards make some efforts to enforce accountability, often it’s accountability related to things there’s little reason to think benefits students. Crabill describes the following example of how school boards typically operate:

A school board noticed that middle-school reading levels were low. The school board met with the superintendent about this matter, and one of the school board members introduced a literacy curriculum he’d learned about at a conference. “This curriculum is specifically designed to serve the needs of school systems just like ours,” the school board member explained. “This can help us address our low literacy rates. We should implement it.” The superintendent wasn’t thrilled by the idea and explained that they already had a lot on their plate. If this new curriculum was adopted, other items would have to be removed from the current list of responsibilities, items that the annual bonus was tied to. After some discussion, the board and the superintendent came to an agreement. Some of the superintendent’s other responsibilities would be removed to make room for the new program, and his annual bonus would now be aligned with implementing the literacy curriculum under consideration. With these changes approved, the superintendent began the process of adopting the new literacy curriculum for all middle school students. A third-party group of consultants was brought in to focus on literacy, and the curriculum was implemented with fidelity. At the end of the year, the board was satisfied that the curriculum had been implemented correctly, and the superintendent received his bonus.

Crabill then asks a fundamental question:

What’s missing from this story? As well-intentioned as everyone was, this school board approached the situation with an adult-inputs-focused mindset rather than a student-outcomes-focused mindset. But they are not alone. Many generations of school boards have been baptized in the adult-inputs-focused mindset. It lives in how school board members are trained, how we are lobbied in grocery stores and church basements, how our school board meetings are focused, and if we are elected, it lives in how we campaign. Because this school board operated from within an adult-inputs-focused mindset, resources were aligned with the superintendent implementing the recommended curriculum. A lot of money was spent to set it up, and the bonus was given to the superintendent for his work to implement the new curriculum. Inside of a student-outcomes-focused mindset, the board would have said, “Your evaluation will always be based on whether or not the students learn to read at age-appropriate levels.” In the end, middle school literacy did not improve in this school system, resources were spent on a curriculum that did not deliver on its promise, and a superintendent received a bonus that was earned, but not for improving outcomes for students.

As Crabill writes, underlying this problem is a failure to fully appreciate the following:

School systems exist for one reason and one reason only: to improve student outcomes. This is the only reason that school systems exist. School systems do not exist to have great buildings, have happy parents, have balanced budgets, have satisfied teachers, provide student lunches, provide employment in the county/city, or anything else. Those are all means—and incredibly important and valuable means—but none of them are the ends; none of those are why we have school systems. They are all inputs, not outcomes. None of those are measures of what students know or are able to do. This idea might sound obvious, but in the middle of facilitating this conversation once, a school board member interrupted me. “Student performance is not one of our jobs,” the board member asserted emphatically. When I countered, she replied that “our job is to pass the budget, make policy, and hire a superintendent.” This is the adult-inputs-focused mindset hard at work. She was not a “bad” person, but she was trapped inside an ineffective school board member mindset. And not because she didn’t believe deeply in what’s possible for students; she did. She was less effective because whatever actions she took were grounded in her focus on the activities of adults rather than on data about the outcomes of students.

Concerns regarding the outcomes of students should always be paramount among school boards, especially when learning losses have been so steep following COVID-related school closures. As Nat Malkus of the American Enterprise Institute writes:

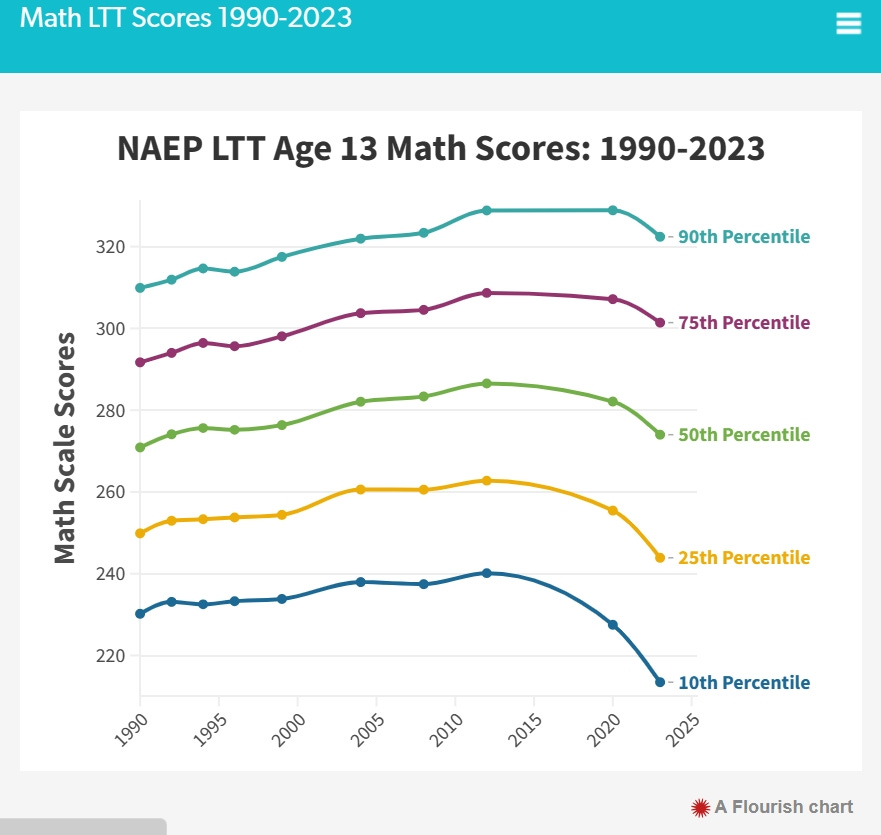

A new round of national test results, the Long Term Trend (LTT) Assessments from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), was released last week … Another worrying trend in these [results is that while there are losses for all students, the floor is falling out from under our lower performers. The first figure below shows changes in LTT Math scores between 1990 and 2023 for students scoring at the 10th through 90th percentiles. In both math and reading, (click the tabs in the figure to see different scores) the highest scores were recorded in 2012, with declines by 2020 and even greater declines by 2023. Students at the 10th and 25th percentiles saw larger declines after 2012 than their peers at higher percentiles showed. These differences look relatively small because the scores range over 110 points, making differences between the highest and lowest scores stand out more than the differences within those groups.

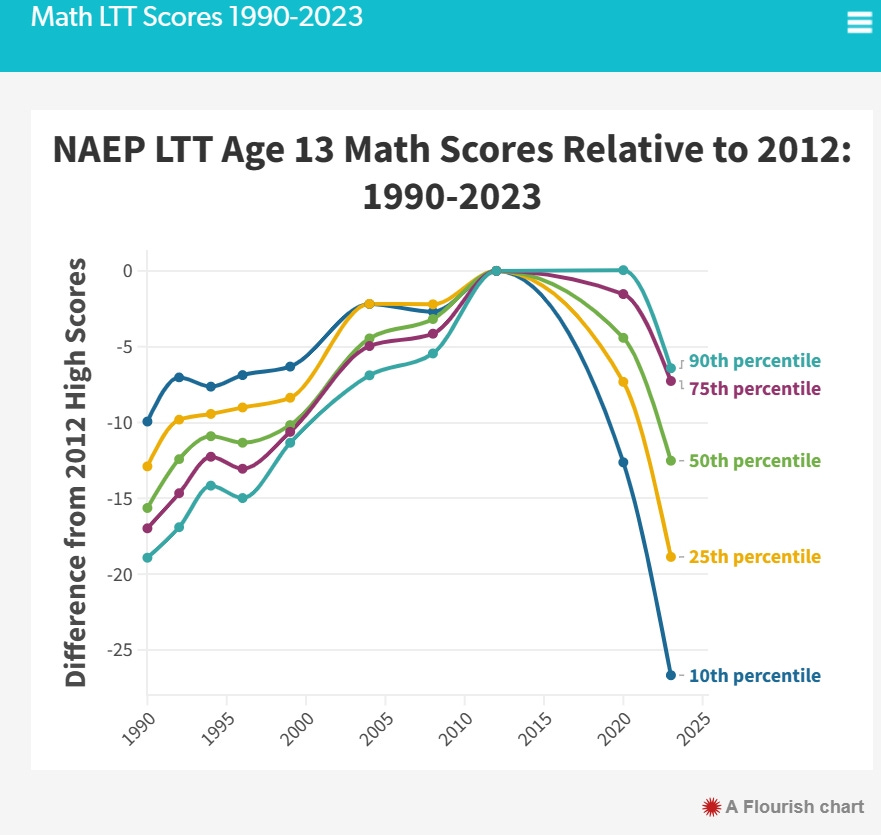

By changing the scale, the second figure clearly shows how much larger losses are for lower percentiles. This graph plots the same data as the one above, but subtracts the 2012 high score for each percentile from the corresponding scores from other years. By subtracting the 2012 score for each group, the 2012 scores all become zero, and the graph’s scale shrinks from 110 to 30 points. This makes the relative test score changes since 2012 come into sharp relief.

Over the last 11 years, declines at the 25th percentile in math scores of 13-year-olds were well over double those at the 75th, and those at the 10th percentile were quadruple those at the 90th percentile. The shift at the 10th percentile is enormous, at over two-thirds of a standard deviation. The patterns seen in math are also evident on the LTT Reading test … but at mercifully smaller sizes. Since 2012, the 10th percentile reading scores are down 31 percent of a standard deviation (still a whopping decline), compared to 9 percent for the 90th percentile. If this seems like a bright spot, it is not; it’s just a calamity that is smaller than the one we see in math. Unfortunately, the performance of 9-year-olds on the LTT was similarly dismal, and the results on the main NAEP tests in reading, math, history, and civics reflect trends that are just as worrying … Academic achievement is down for American students as they enter high school, particularly for our lowest-performing students. The consequences of this lower achievement—which typically includes all sorts of negative life outcomes from lower incomes to higher incarceration rates to larger waste lines—will take enormous efforts from schools, families, and students to avert. Indeed, nothing less than Herculean efforts will make up for such shortfalls.

Yet, as mentioned in the previous essay, one member of our local school board who works for the American Federation of Teachers union has taken up the cause of promoting a change to the school board election system in which school board members will be elected in staggered (and potentially longer) terms, in order to promote “continuity in policy,” when the school board has spent virtually no time developing any policy to improve student learning outcomes. (At an October 5, 2023, meeting, the board took a straw poll in which, as reported by a local paper, “The Board kept three options at the end of the session, all of which increase terms to four years [and] maintain the nine-member structure.” Not surprisingly, the board expressed its disapproval of reducing its own size, and expressed its approval of lengthening the time between elections.) At a time when students are struggling to make up for the learning losses caused by school closings during the COVID pandemic, the new proposed policy, while it may help school board member adults, has no reasonable relation to the goal of improving student educational outcomes for kids. As Crabill writes (regarding a similarly tangential debate he became aware of on the proper color for school buses):

There is a vital lesson to be gleaned from these school board members spending time debating school bus yellow: how the board invests the rare, precious moments it has matters immensely. The tragedy in this nonyellow school bus debate is that, during those two weeks when everyone put time, energy, and effort into the matter of school bus colors, the board members, administrators, and teachers were not solely focused on whether children were learning. Students suffered from that lack of focus … Effective school board members place the highest premium on whether or not outcomes for students are improving rather than focusing on what is being done by adults (how the money is being spent, which persons are being hired, which colors are selected, which vendor is selected, etc.). Effective school boards care about these things too—the “how” it all happens—but they know that anytime school boards are focused primarily on the “how,” they have stopped being focused primarily on the “why”—whether or not children are better off.

Crabill is clear about what exactly needs to happen for a school board to even hope to be effective in improving students’ educational outcomes:

A truly balanced school board would focus 50 percent of its board meeting time each month on clarifying priorities and/or monitoring progress. saying, “school boards should just focus on policy” but then never actually setting Goals about student performance or monitoring them. Policies that aren’t monitored aren’t actually priorities. saying, “school boards should be responsive to the taxpayers” but then not focusing on return on taxpayer investment. If return on investment (ROI) is actually important, the “return” can only be known if priorities have been clarified and then progress toward them is monitored. Absent those two steps, it’s impossible to know if the taxpayers are experiencing a return. The only way to be responsive to taxpayers is to be focused on student outcomes. saying, “school boards should also focus on goals about student experiences, not just student outcomes.” Students having a positive learning experience is a means, not an end. If schools ensure that children go on field trips and are happy about their schooling, but the children don’t actually learn anything, that is not victory, that is malpractice. A wonderful culture and climate is an adult input, not a student outcome; it is necessary but insufficient, and it’s neither why school systems exist nor why school boards exist.

Crabill then describes how he conducts advice sessions with various school boards:

“On a scale of one to ten, write down how focused you are on improving student outcomes,” I directed the school board members. This was our first session together so, as usual, I started with a quiz to help baseline where the school board was at. Most school board members said that they were sevens, eights, or nines, but one brand-new school board member proudly declared that she was an eleven. I just smiled and continued. “How many Goals has your school board adopted about student outcomes?” I asked. The school board members all seemed slightly confused by this question. After some discussion, they finally arrived at the inescapable conclusion they needed to see: the school board had adopted zero Goals about student outcomes. I could tell in the back of their minds that those sevens, eights, and nines were starting to seem very suspect. But we hadn’t even gotten to the clencher yet. “Here’s a copy of the minutes and agenda from your most recent school board meeting. Take a moment and read through it and then write down the percentage of time during this meeting that was focused on student outcomes.” I let them work for a while, then I asked for their percentages. After some back and forth, it quickly became obvious that there was only one correct answer: in the absence of having adopted Goals about what students should know and be able to do, it was impossible for the school board to have focused any of the meeting on their Goals for what they wanted students to know or be able to do … This is why, years ago, my team and I began tracking and coding board meetings to identify how much time the average school board focuses on student outcomes. More recently, it has expanded nationwide through the Effective School Board Initiative (ESBI). Wanting to figure out what percentage of time each month board members spend on student outcomes across various meetings, we coded hundreds of meetings over six years. This has led to a sobering conclusion: Most school boards spend between 0 and 5 percent of their time monitoring progress relative to their Goals for student outcomes, with the majority of school boards spending less than 1 percent … Finally, I returned to where we began: “As you reflect on the percentage you just wrote down regarding the meeting and the ‘focused on student outcomes’ score you gave yourself earlier—as you compare these two things—what are you noticing?” Then I sat quietly as seconds ticked away in complete silence. The school board chair, a student advocate I’ve come to strongly admire, was the first to raise her hand and speak into the void: “I’m noticing that I’m not at all focused on student outcomes.” … [I]t’s never enough to simply love children and want to make a difference. You have to be able to do the work effectively.

I thought that was a good exercise, so I perused all the agendas for our local school board meetings going back to the beginning of 2022, and those agendas reveal no attention to the goal of improving student educational performance and measuring improvement toward that end with objective metrics. And soon in Virginia, issues related to teacher compensation and benefits will come to dominate the school board agenda now that collective bargaining is underway. I’d invite readers who are also interested in the performance of their own local school boards to go through the same exercise of perusing published school board agendas to see how seriously they’re taking improving educational outcomes. You might also click on archived school board meetings in your area and randomly click around the videos to get a sense of what percent of the time the school board is spending on defining goals for improving student achievement and verifying progress toward that end through objective measures. You may be shocked (as I was) at the results.

Incidentally, the notice sent out announcing the question and answer session at the local park (mentioned earlier) suggests several topics for discussion, none of which relate to improving student academic performance as measured by objective tests:

Interestingly, Ms. Booz only announced her next question and answer session with constituents on her union X account, and not on her official school board member account.

It’s particularly concerning that the City of Alexandria’s school board spends virtually no time discussing ways to improve student learning when the Virginia Department of Education requires “Standards of Learning” tests in various subjects, and in my own City of Alexandria, Virginia, as reported in the Alexandria Times:

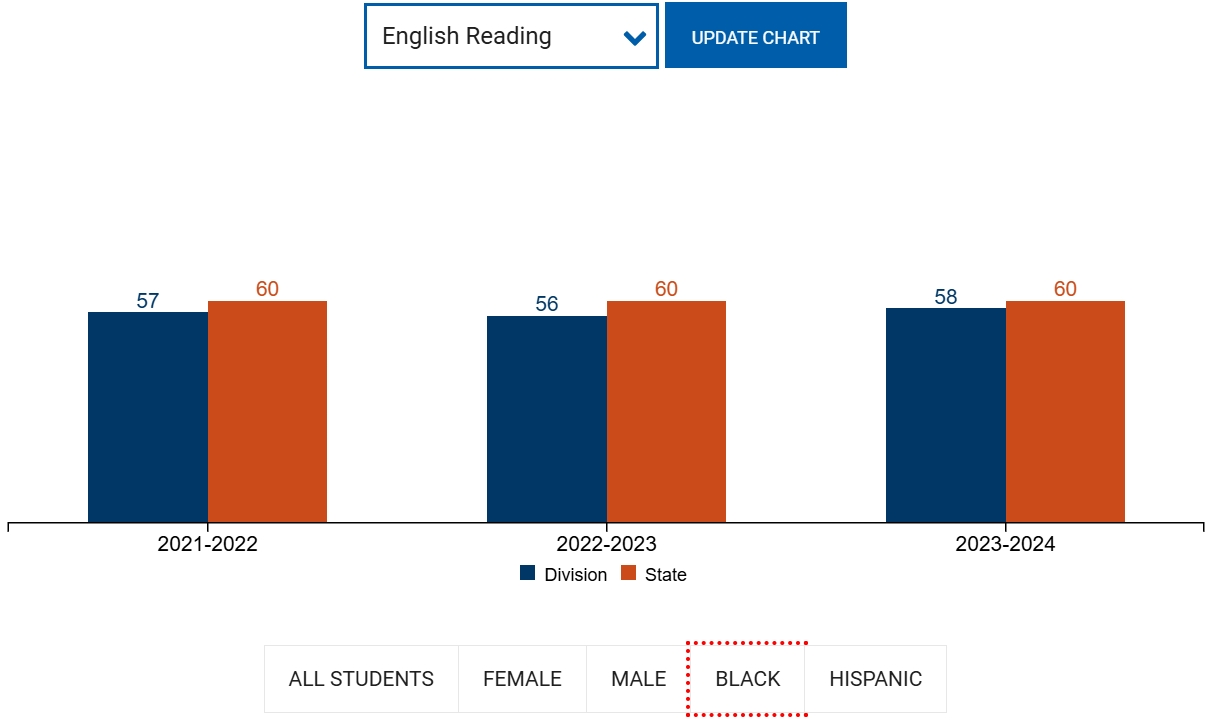

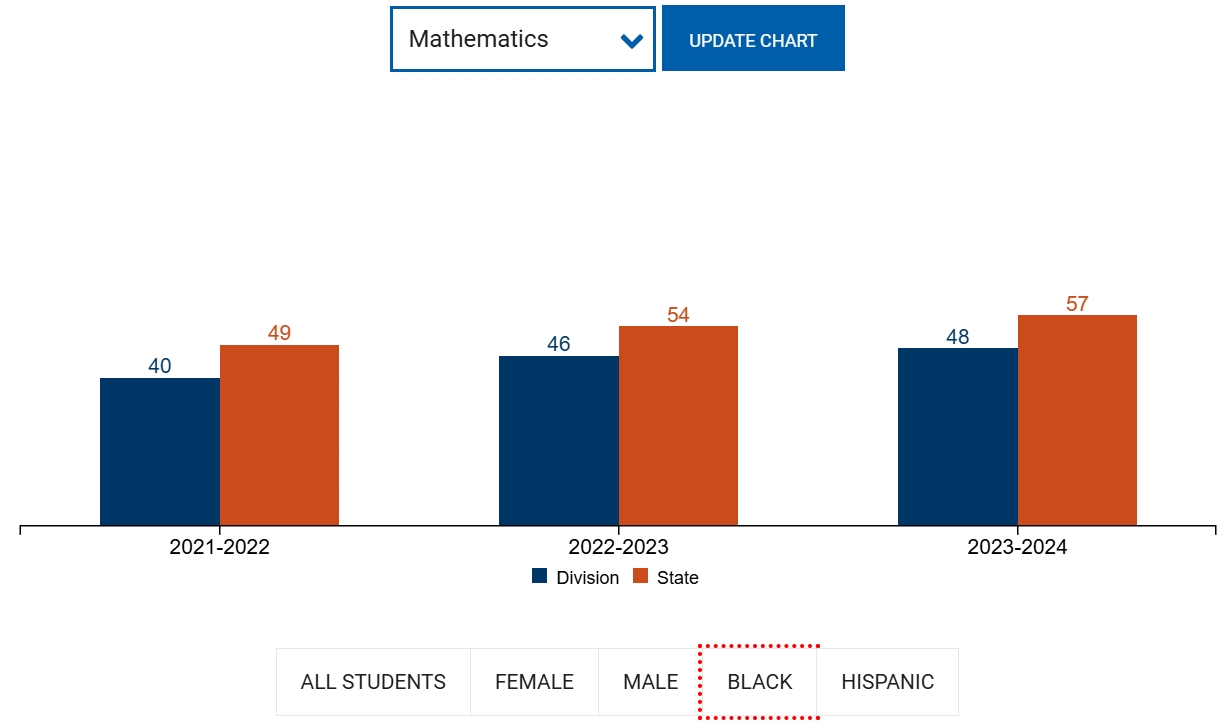

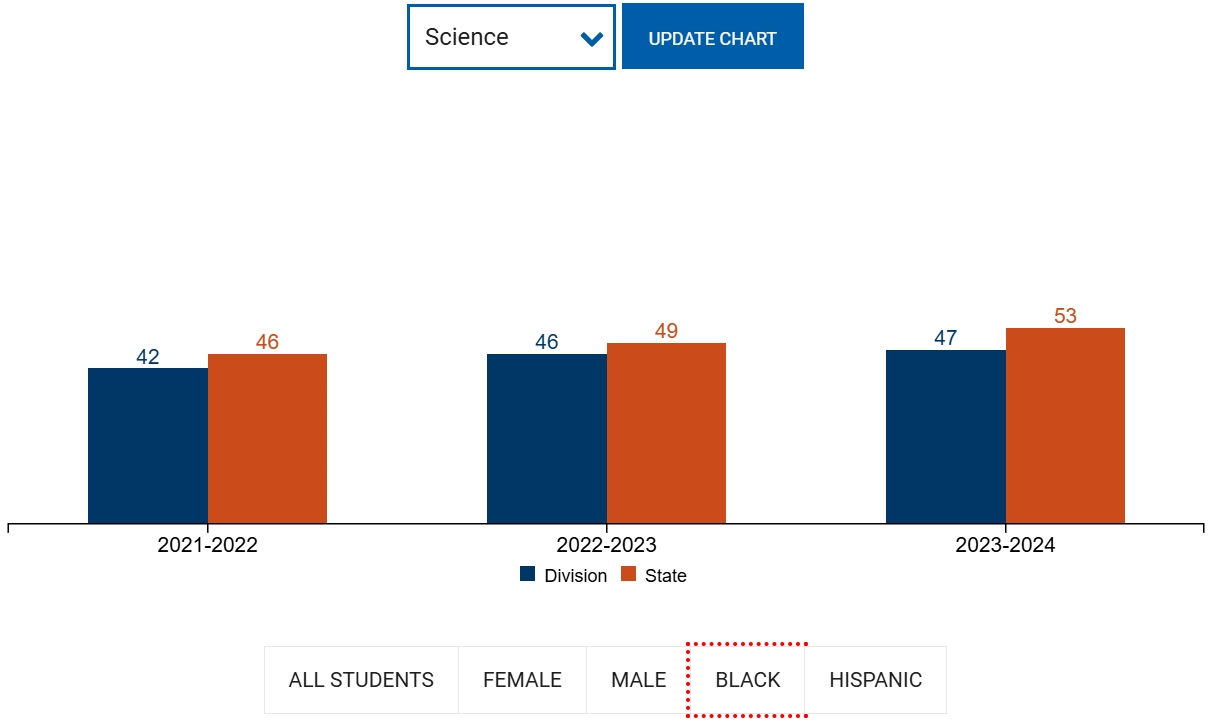

The performance of [Alexandria City Public Schools] lagged behind that of Virginia as a whole in every category by at least 11 percentage points, with Alexandria students achieving a lower than 50% proficiency in both math and science. The SOL scores were released by the Virginia Department of Education last week. For the 2021-2022 school year, ACPS had a pass rate of 60.94% in reading; 62.39% pass rate in writing; 53.90% pass rate in history and social science; 48.64% pass rate in mathematics; and 48.68% pass rate in science. Comparatively, the 2021- 2022 VDOE statewide results revealed a pass rate of 73.12% in reading; 64.74% pass rate in writing; 65.75% pass rate in history and social science; 66.37% pass rate in mathematics; and 65.01% pass rate in science. Alexandria’s performance in math was 17.73 percentage points lower than the statewide totals, while the science scores were 16.33 percentage points lower than Virginia as a whole. According to Charles Pyle, VDOE director of communications, the results are somewhat misleading because the state introduced new reading tests in 2021 that require lower proficiency benchmarks, meaning they were easier tests than previous school years.

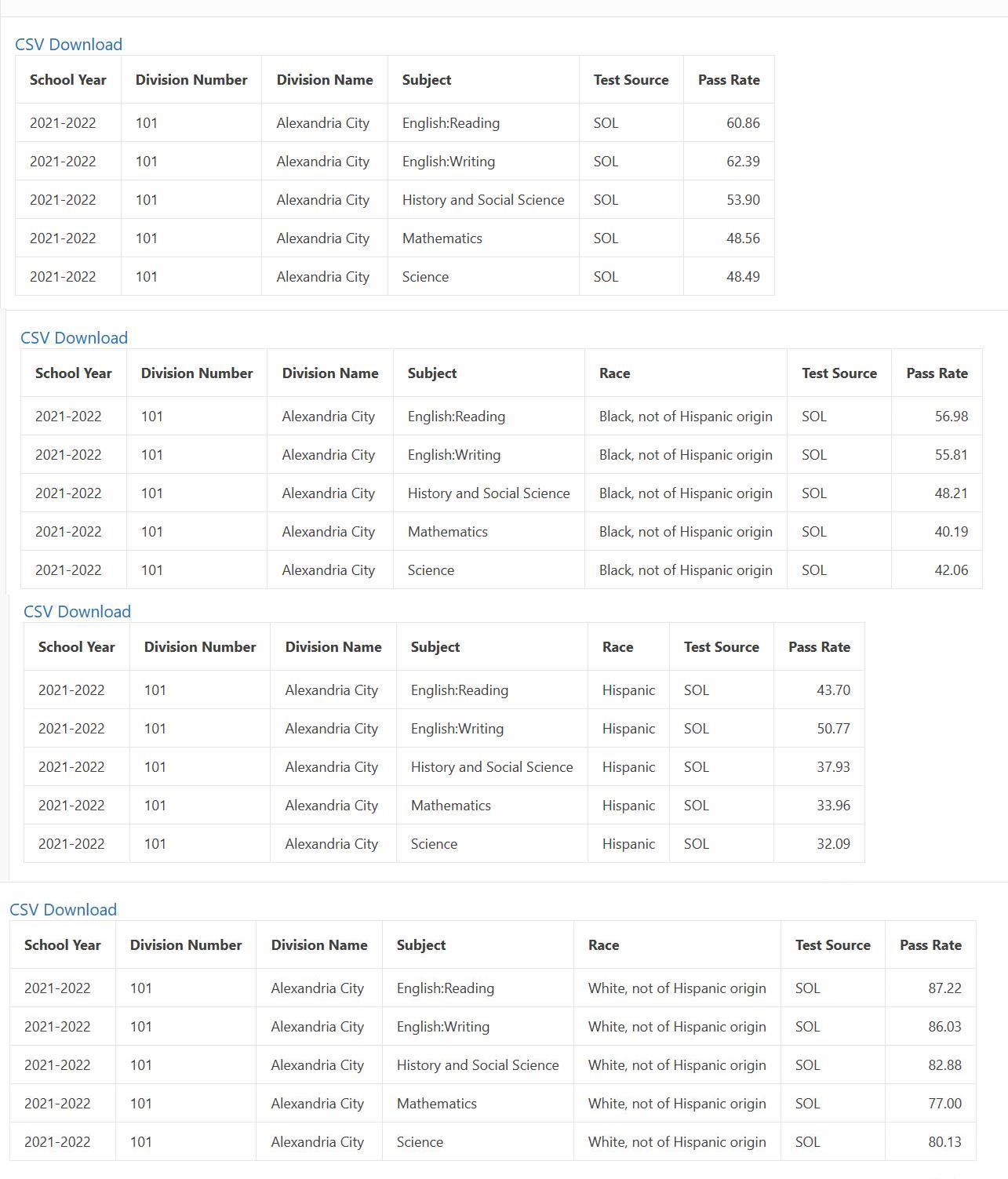

Here are the “Standards of Learning” (SOL) test pass rates for Alexandria City schools for the year 2021-2022, followed by the pass rates broken down by race:

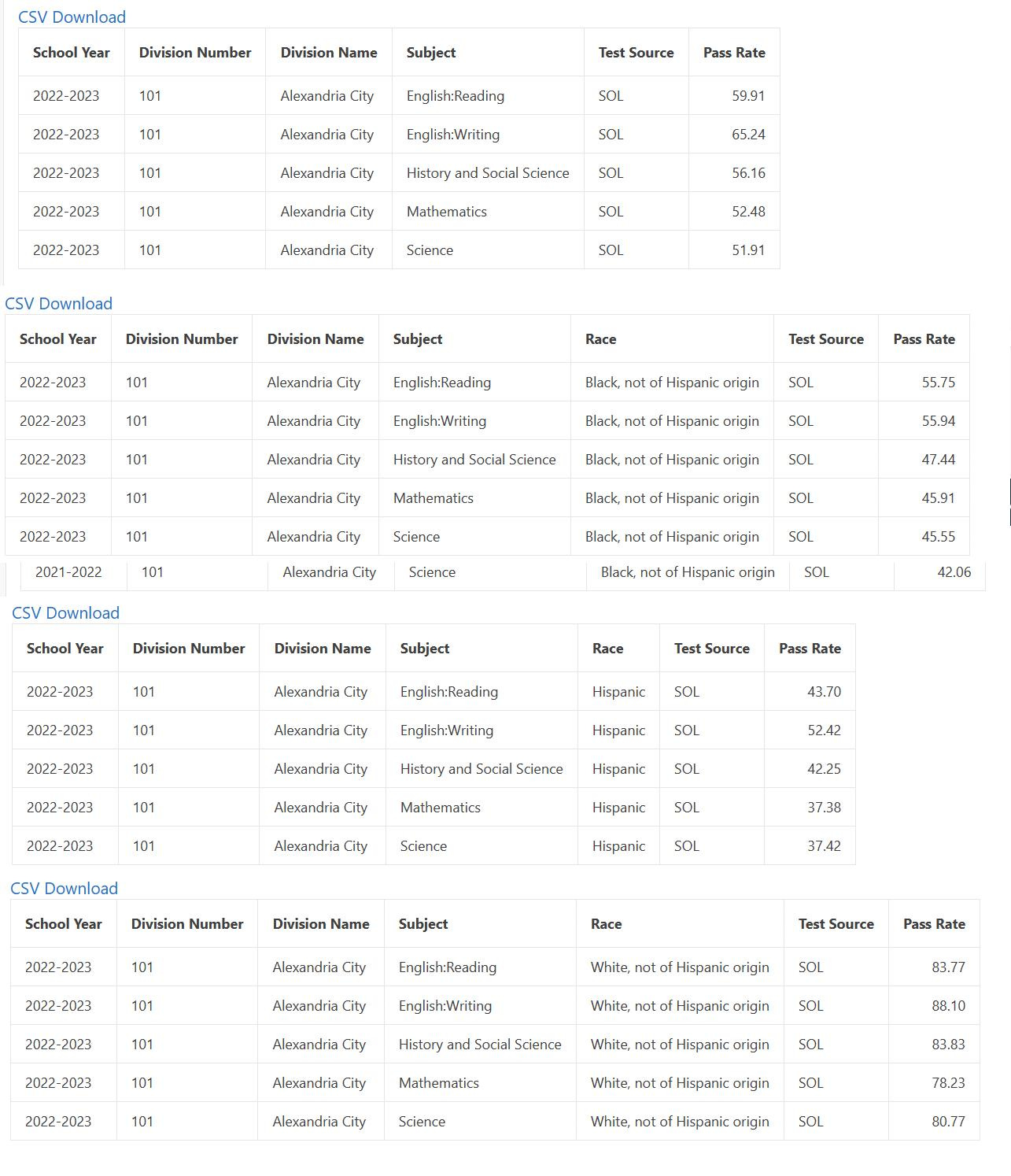

Of course, once students could resume in-person schooling, there were bound to be at least some minimal gains in learning. But the 2023 scores hardly moved the needle, and test scores in reading even went down a point. Pass rates of 60% for reading, 65% for writing, 56% for history and social science, 52% for mathematics, and 52% for science are cause for grave concern, not celebration (and from 2022 to 2023, the black student pass rates in reading and history and social science actually went down):

Further, as the local Alexandria Times newspaper reports:

ACPS achievement still trails significantly behind the average Virginia school district in four of the five categories, which are reading, writing, history/social studies, math and science. ACPS scores are also well below the district’s performance during the 2018-2019 school year, which was the last full year prior to the COVID- 19 pandemic … While ACPS matched the statewide SOL score in writing, with a 65% pass rate, Alexandria continues to lag significantly behind Virginia’s average pass rates in the other four subjects. The widest disparity was in math, where Alexandria’s 53% pass rate lagged 23% behind the overall Virginia math pass rate, which was 69% during the 2022-23 school year. Alexandria’s reading pass rate was 60%, which is 17.8% lower than the Virginia pass rate of 73%.

And regarding the city’s only high school, the high school newspaper reports:

[Alexander Duncan, the Executive Principal, says] “The data has shown us that we as a school have got to find a different way to do what we do so that we can meet [the needs of] more young people … I worry about the 16 percent of students who are not graduating. That’s serious to me.” In addition to its low graduation rates, ACHS [Alexandria City High School] has recently struggled to meet state averages for standardized test scores. Last school year, the majority of students taking the Virginia Standards of Learning (SOL) exams for math, science or history did not pass … The school is currently “credited under conditions” by the Virginia Department of Education and is at the risk of losing accreditation entirely, although it is unclear when this would occur. If accreditation were lost, the state would take hold of ACHS and could subject it to extreme measures, including possible termination and re-hiring of all teachers.

Still, the Alexandria City School Board held a pat-on-the-back session to celebrate these poor results:

Math and science scores had particularly notable declines compared to reading and writing, which are closer to 2019 scores, according to Page, but that gap narrowed over the last year. School Board Vice Chair Kelly Booz said it’s inspiring to see forward academic progress, though she acknowledged there’s still work ahead. “We’re moving in the right direction across all categories,” Booz said.

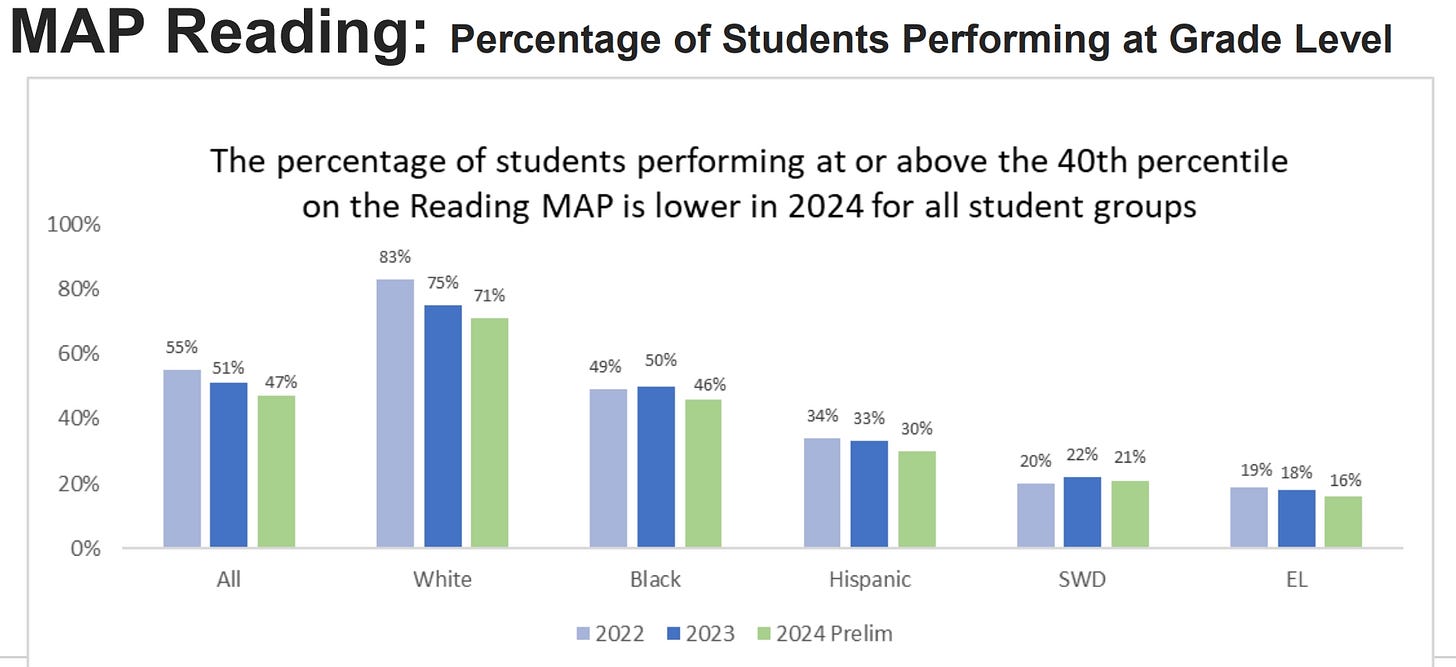

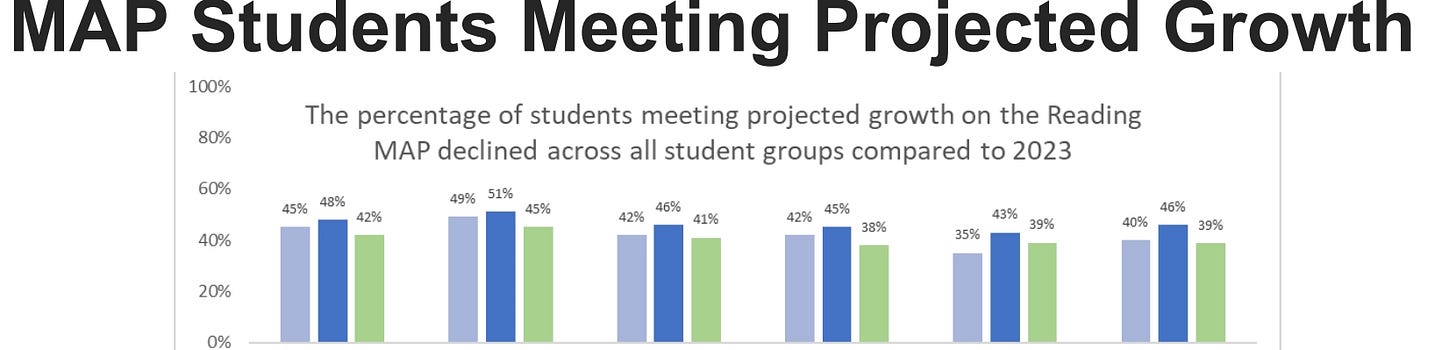

As anyone can see from the Standards of Learning pass rates from 2022 to 2023, the statement that “We’re moving in the right direction across all categories” is false. Indeed, the percentage of students performing at grade level is lower in 2024 for all student groups in the City of Alexandria, Virginia school system.

As a local newspaper reports, regarding the 2023-24 local school district test scores:

According to Virginia Department of Education data released Tuesday, the English reading pass rate for ACPS was 61 percent, up one point from the previous year. The math pass rate increased from 53 to 55 percent, the science rate increased from 52 percent to 53 percent, and the English writing rate increased from 65 percent to 71 percent. The history pass rate had the greatest jump — from 56 percent to 64 percent. The ACPS pass rates remain lower than the state average, although the ACPS history pass rate is just one point away. The state averages were 73 percent in English reading, 71 percent in math, 76 percent in English writing, 65 percent in history/social science, and 68 percent in science.

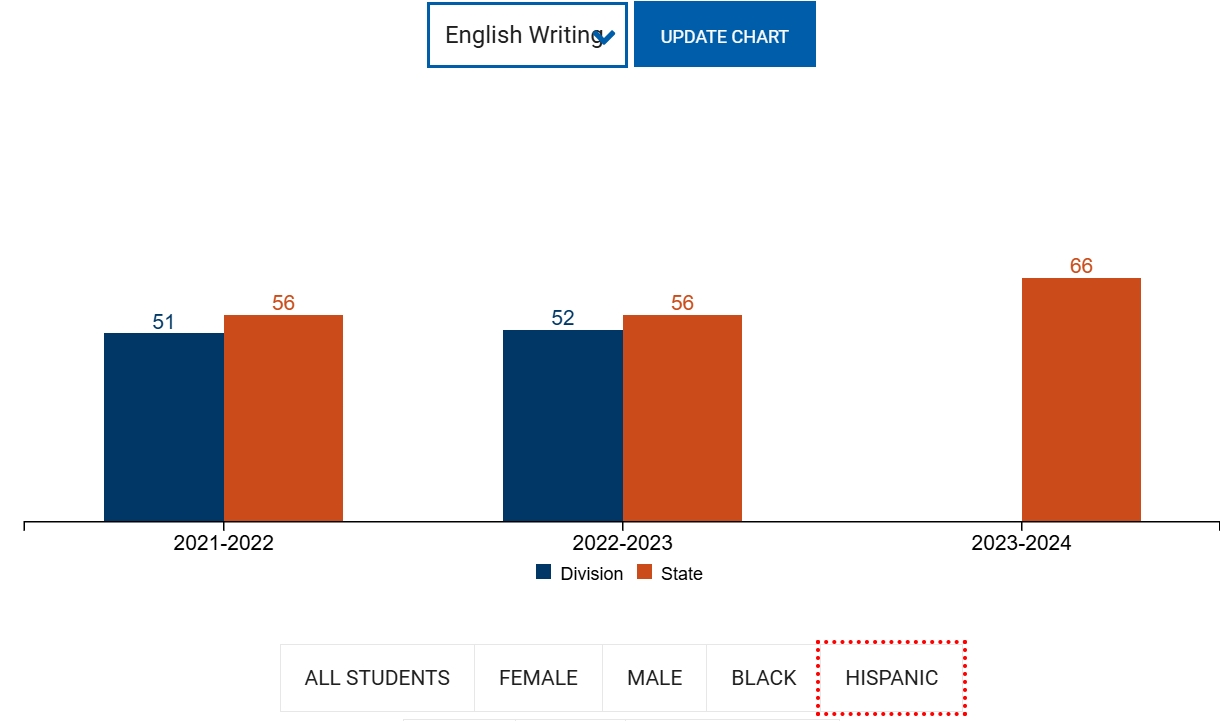

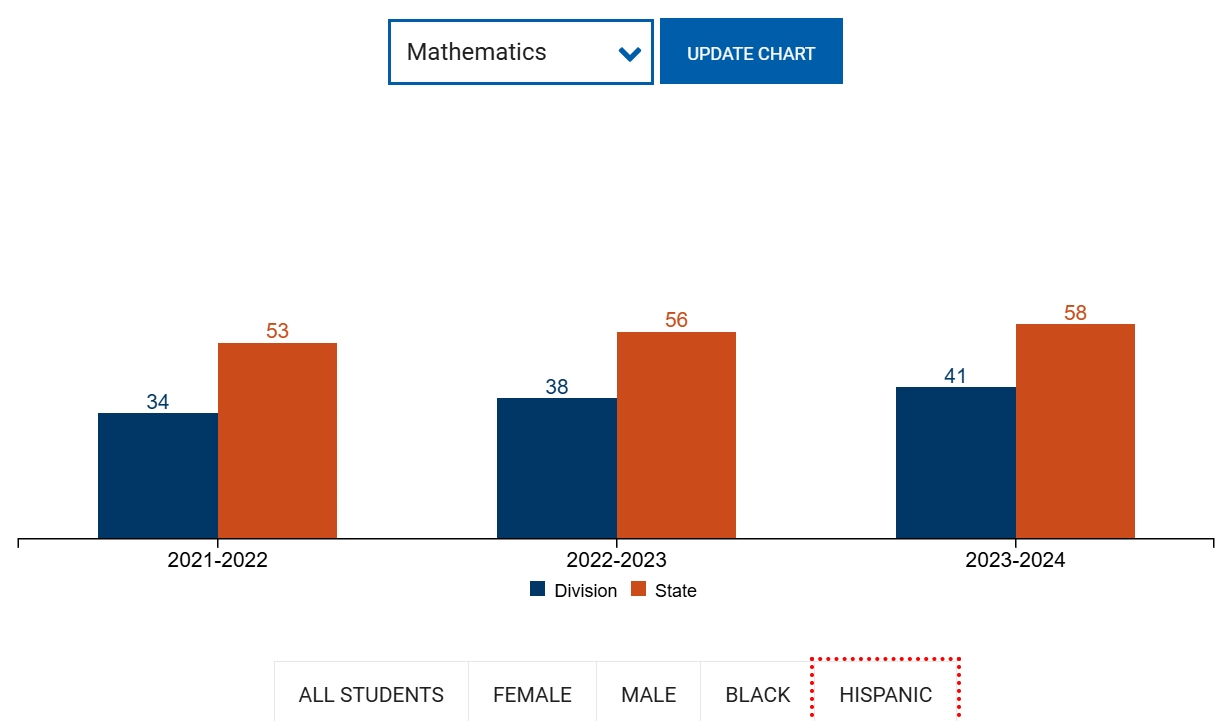

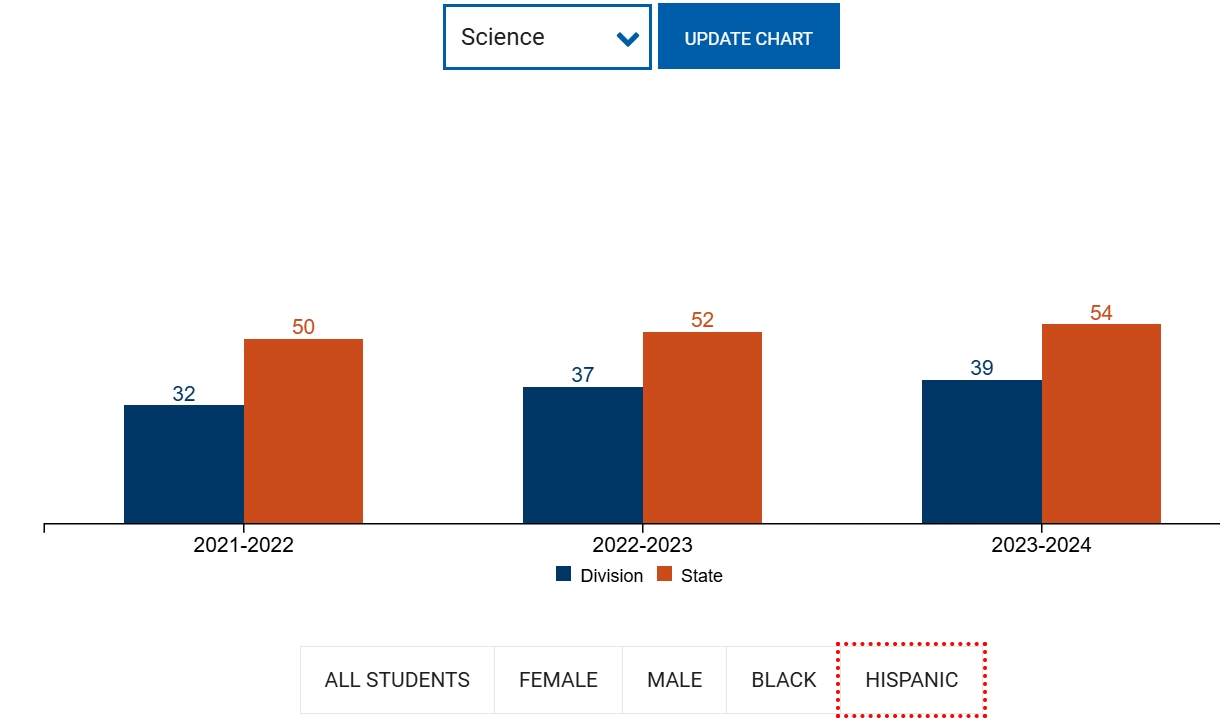

Sadly, the black and Hispanic students in our local school district perform worse on these tests than black and Hispanic students statewide, on average. Below are the graphs showing results for the reading, math, and science tests.

Regarding the small gains that were made in these SOL scores across the student body, Pierrette Finney, the chief academic officer at the Alexandria City Public Schools, “credited Virginia’s ALL In Tutoring initiative – which provided additional funding and instructional resources to ACPS – as a potential reason for increased SOL scores this year. The ALL In Tutoring program is a statewide initiative that was launched on Sept. 8, 2023, by Gov. Glenn Youngkin in response to the release of the 2022-23 school year SOL scores. The initiative created a statewide tutoring network in reading and math to help third grade through eighth grade students accelerate their learning.”

As Frederick Hess writes:

Social and emotional learning served as a case study in allowing the righteous to displace the routine. Launched decades before by advocates who billed it as a way to equip students for academic success, it was overrun by ideologues eager to harness it to bespoke agendas. Educators were told that traditional grading was suspect. They were told that discipline was oppressive and urged to shift from “punitive” practices to more “restorative” models. They were told that testing was inhuman and unfair. They were told that multimedia literacy was just as important as textual literacy. They were told that phonics instruction was constricting and unnecessary. They were told that content knowledge was overrated, that students could always “look things up.” The irony? When traditional norms erode, the biggest losers are the students who aren’t getting structure, discipline, or high expectations at home. It’s no surprise that our NAEP woes have been most pronounced among low-achievers.

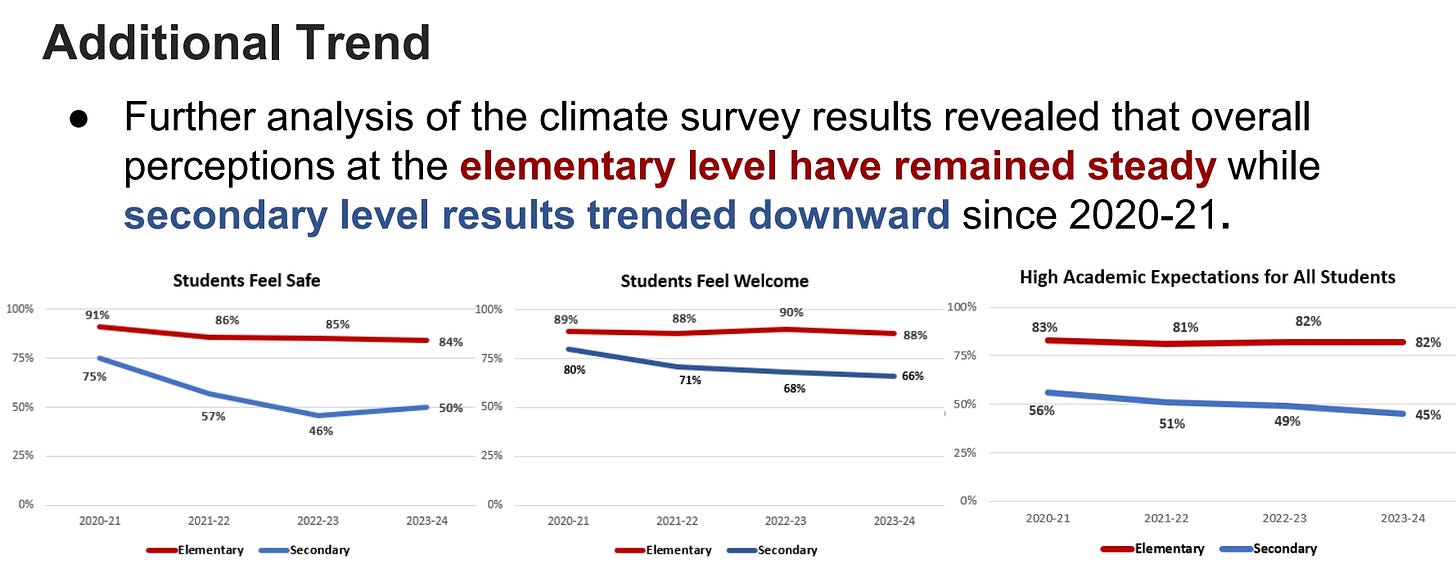

Further, the school system’s surveys report that secondary school students report progressively worse perceptions of safety and worse perceptions of expectations for high academic standards for all students.

As Crabill writes:

[C]ommunities choose to continue having school systems for one reason only: to increase what students know and are able to do, to provide students with knowledge and skills, to improve student outcomes. This is why school systems exist … [T]he school board … [ideally] creates a set of policy statements that describe the next measurable milestones that need to be achieved to move the school system in the direction of accomplishing the vision … To be useful, the Goals must meet several criteria, otherwise they aren’t Goals, they’re just platitudes that benefit adults politically while not benefiting student outcomes. Goals must: … be grounded in student performance data, the current reality for students; [and] be SMART—specific, measurable, attainable, results-focused, and time-bound … Effective Goal setting requires describing both the currently known level of student performance and the desired level of student performance in three to five years … [T]he school board will need a one- to five-page summary of the superintendent’s findings regarding student data. With this document in hand, the school board not only has useful information for Goal setting, but it also has meaningful evidence that demonstrates to the community that the school board’s decision-making is grounded in student outcomes … Continuous improvement — both in the classroom and in the boardroom — requires having a clear measure of what you are trying to accomplish, then implementing a strategy, then routinely measuring to clarify whether you are moving toward or away from the desired accomplishment, and then the discipline to make adjustments and begin implementing again. Vague statements about what you are trying to accomplish won’t set you up for success. You will need Goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, results-focused, and time-bound: SMART … The Goal needs to specify exactly what is being measured and preferably what the system of measurement will be. It is more effective to say, “the percentage of students who have demonstrated on grade-level literacy skills using the XYZ assessment” than to say, “the percentage of students who have demonstrated literacy.” Once a measure has been identified, then the Goal will need to state what percentage of students need to improve in that area. In addition, Goals need to include a starting point that describes what the students know now, and an ending point that describes what we want them to know. It is more effective to say, “The percentage of students who have demonstrated on grade-level literacy skills using the XYZ assessment will increase from a-percent to b-percent.” … Effective school boards adopt Goals that intentionally cause disruption within the organization. That goals are disruptive is a feature, not a bug. It is common for school boards to adopt goals that are easily accomplished, but this behavior benefits adults—they get to pretend that children are improving—while harming students … Goals require some type of measure of what students know or are able to do. As such, you can’t have a Goal without having assessment data on which to base the Goal. If a Goal isn’t measurable, then adults are simply invited to pretend whether or not students were benefited by the Goal. This practice tends to be most harmful for students who are already the most vulnerable … Many professions — medicine, technology, engineering, construction, truck driving, and more — rely on standardized assessment as part of their systems for promoting fairness and ensuring performance.

And this is at a time when the prolonged school closures pushed by teachers unions during the COVID pandemic led to dramatic drops in academic achievement among students, especially among black children. As reported in the New York Times in June, 2023:

The math and reading performance of 13-year-olds in the United States has hit the lowest level in decades, according to test scores released today from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the gold-standard federal exam … The federal standardized test, known as NAEP, was given last fall, and focused on basic skills. The 13-year-olds scored an average of 256 out of 500 in reading, and 271 out of 500 in math, down from average scores of 260 in reading and 280 in math three years ago … Achievement declined across lines of race, class and geography. But in math, especially, vulnerable children — including Black, Native American and low-income students — experienced bigger drops. A large body of research shows that most American children experienced academic struggles during the pandemic. It has also been clear that low-income students of color were most heavily affected by school closures and remote learning, which in some districts lasted more than a year.

(Our local schools here in Alexandria, Virginia, were closed in March, 2020, and didn’t fully reopen until August, 2021.)

The NAEP results also show that “The percentage of 13-year-olds enrolled in algebra has declined to 24 percent from 34 percent in 2012,” and, as the New York Times reports, “In some districts and states, notably California, there has been a push to equalize math education by placing fewer eighth graders into advanced math.” Our local school system in Alexandria, Virginia, is also considering eliminating advanced math classes. As I’ve written previously:

[N]ot only is our local school board entirely avoiding the question of educational methods and their results, it’s apparently considering eliminating advanced math classes. I say “apparently” because there seems to be some confusion about the proposal. At a May school board meeting, there was discussion of “Middle School Project Mathematics Pathways.” That presentation to the school board featured an official essentially reading the text of Powerpoint slides to the board about the project. One of those slides stated that a “Key Recommendation” of the program was that “Middle school mathematics should dismantle inequitable structures, including … the practice of ability grouping and tracking students into qualitatively different courses.”

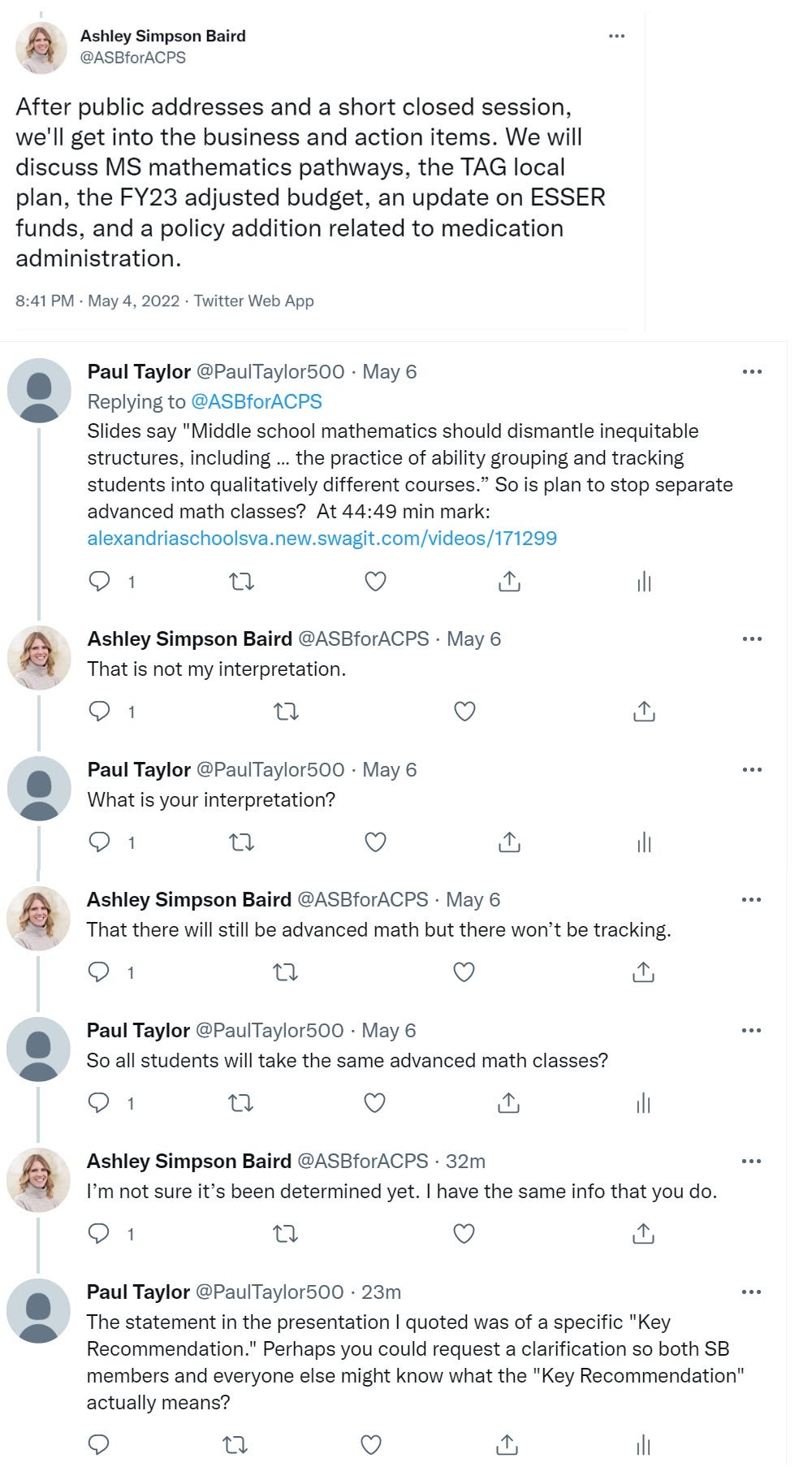

I wondered what that actually meant. During the question and answer period that followed this presentation, no school board member asked for any clarification, so I asked two of my district school board representatives what the proposal actually meant (only one of the two representatives responded), and the result was the following Twitter exchange:

As I write in a subsequent essay, “Apparently, going forward, our local school board is abolishing the current system that allows students who have the demonstrated capacity to handle more challenging math problems to experience those challenges in their own classes specially designed to get them a year ahead in math. This seems to have happened on June 1, 2023, at a school board meeting at which there was no debate or public vote on the issue (see item 15 of the school board agenda of that day, available here, but note there is no corresponding link to any public debate or vote on that issue).”

I also wrote previously about a local school board proposal to prohibit giving students zeroes for homework not submitted (to further the interests of “equity”) even though that policy would only incentivize students’ doing less homework. A similar policy was enacted in nearby Fairfax County, but subsequently reversed after disastrous consequences. According to a local news report:

In an update to its grading policies, Fairfax County Public Schools said teachers can now give students a zero for an assignment that’s not turned in. The change marks a departure from previous guidance, which said 50% is the lowest grade a teacher can give to a student who doesn’t turn in work. It comes after the state’s largest school system convened a working group to evaluate its high school grading policies last fall … “If you do nothing, then you get nothing,” [a local high school principal] said. “Having that zero in place, it tells the correct story, and it gives you the real picture of what’s going on.”

As one teacher said at a June, 2023, question and answer session with two local school board members, “It seems to be [the school system’s] response, when there’s an inequitable issue, is to drag people down, to make everything the lowest common denominator, when in reality what it should be is, how do we get everybody what they need?”

Further, Crabill writes, “A school system can’t be effective if it’s trying to pursue a myriad of incoherent visions while implementing a cacophony of conflicting values.” When I read that line, I recalled that our local school district is governed by what’s called the “Equity for All Strategic Plan 2020-2025.” That document, approved by the school board and tweaked every year or so, sets out the school system’s stated goals, and I thought I might look at it again with Crabill’s advice in mind, namely that school boards should use clear, objective metrics to determine progress toward improved student learning, and that subjective tests are useless in that regard because subjective tests are “adult-centered” in that they allow adults to game the system toward preconceived results they can tout for their own political ends.

The first words of the Equity for All Strategic Plan are:

But once you get past that adult-centered self-congratulatory message, the statements in the document get more incoherent.

First, the document is focused not on individual student learning outcomes, but, as I’ve written previously, on the goal of conforming educational outcomes to racial demographics (regardless of individual learning and merit), which is an adult-centered goal that fails to live up to a public education system’s mission of boosting everyone’s educational performance. (That lack of interest in boosting everyone’s educational performance is demonstrated in various charts and graphs provided to the school board in which student standardized test scores are sorted by race, with the racial category of “white” color-coded as “overrepresented” in many metrics listing results in the “40th percentile or higher” range.)

Reading further, the Equity for All Strategic Plan defines the “Achievement Gap” as “the disparity in academic performance between groups of students. The achievement gap shows up in grades, standardized-test scores, course selection, dropout rates, and college-completion rates, among other success measures.” So the document explicitly defines the “achievement gap” with reference to the objective measure of standardized test scores. So far, so good.

However, the document then goes on to define “Educational Excellence” as follows: “We keep the bar high in all we do. We educate students for life and for reflective citizenship. We empower students and employees in the preservation of their identity and culture. Substance, depth, and critical thinking are more important than compliance or test scores.”

Oh, well. So much for holding adult education officials responsible for the need for objectively-measured improvements in student learning. There’s no statement in the Equity for All Strategic Plan of the need to demonstrate educational excellent by improving objective, standardized test scores to reduce the achievement gap, even though standardized test scores are used to define the achievement gap itself in the same document. Indeed, “test scores” are explicitly subordinated to other, higher-priority (and subjective) metrics, namely “empower[ing] students and employees in the preservation of their identity and culture,” with the statement concluding with “Substance, depth, and critical thinking are more important than compliance or test scores.” In this way, the document defaults to subjective metrics adults can tweak to achieve political ends, rather than objective measures that would demonstrate child-centered learning to the benefit of children.

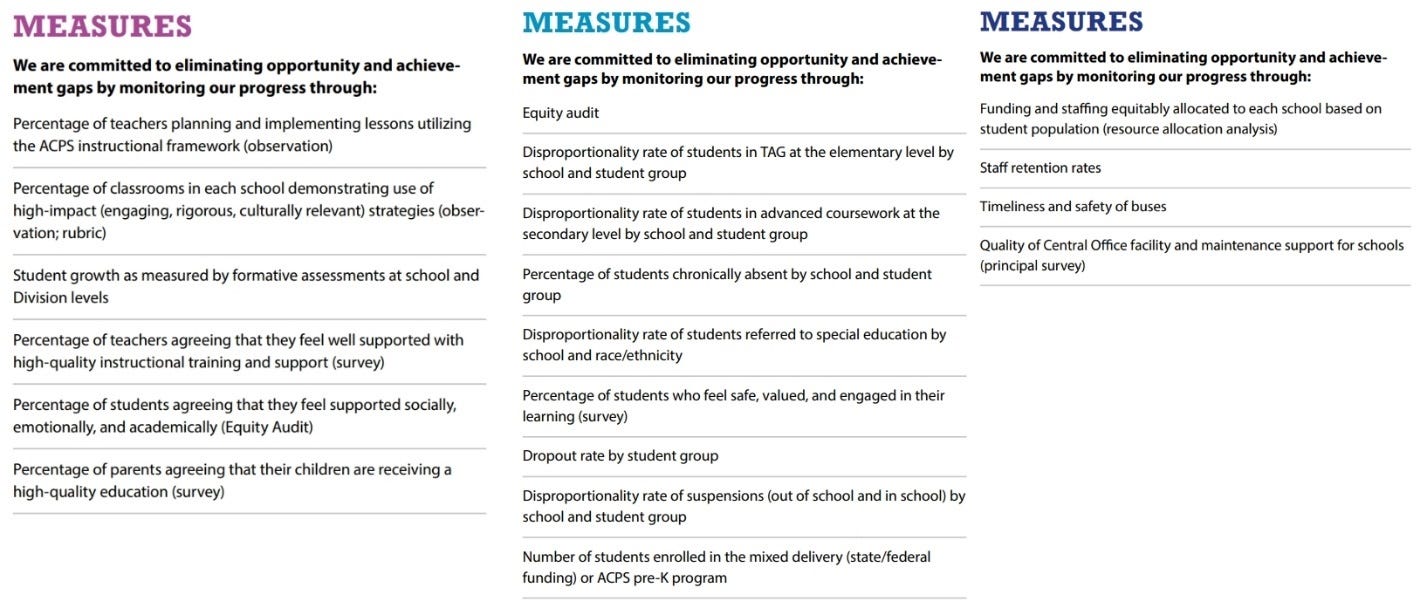

The Equity for All Strategic Plan is even more explicitly “adult-centered” in its listing of various “Measures” that will be used to gauge the success of the plan. Nowhere in the “Measures” listed as defining progress toward the goal of reducing the achievement gap are standardized test scores. Rather, the “measures” are dominated by metrics adults themselves control meeting (or “feelings” students or parents have). The Equity for All Strategic Plan, for example, prefaces these success “measures” with the following phrases:

“Percentage of teachers planning and implementing lessons …”

“Percentage of classrooms in each school demonstrating use of …”

“Percentage of teachers agreeing …”

“Percentage of students agreeing …”

“Percentage of parents agreeing …”

“Disproportionality rate of …”

“Percentage of students who feel …”

“Number of students enrolled …”

“Funding and staffing equitably allocated …”

“Staff retention rates …”

“Quality of Central Office facility …”

As Crabill writes, “It is common for school boards to adopt goals that are about the adult inputs — what the adults intend to do or are doing—but not actually about student outcomes. The norm nationwide is for school boards to be adult inputs focused, rather than student outcomes focused. Effective school boards must make the transition from being adult inputs focused to being student outcomes focused.”

As a side note, of relevance to the “critical thinking” highlighted in the Equity for All Strategic Plan’s definition of “educational excellence,” Crabill writes, “If the community wants children to grow up to be critical thinkers but students aren’t literate enough to read and comprehend complex ideas, critical thinking skills become harder to obtain.” True enough. But in that regard, I was struck by the Equity for All 2025 Strategic Plan’s top-listed “areas of focus for the 2020-2025 school years,” which states:

For those of you who may not have followed the recent scandal over the “balanced literacy” approach to reading, Natalie Wexler, author of The Knowledge Gap, wrote in Forbes that “An eagerly awaited new podcast from journalist Emily Hanford delves into why reading teachers have long been trained to believe in an approach that conflicts with scientific evidence … [W]hat is now the dominant approach to reading instruction, ‘balanced literacy’ … sounds appealing, but its inadequate attention to phonics leaves many kids, and especially those from less educated and lower-income families, unable to read fluently.” It’s shocking that such a discredited reading method (I’d encourage readers to listen to the whole “Sold a Story” podcast series) would be listed as the top “area of focus” for our local school system, but there it is. (At the June 1, 2023 school board meeting, a few tweaks to the Equity for All 2025 Strategic Plan were discussed, but apparently the reference to “balanced literacy” was retained. That same month, the National Council on Teacher Quality issued a report that evaluated 693 undergraduate and graduate teacher training programs. The Council found that 40% of the programs teacher trainers instruct aspiring educators to use center on long-debunked teaching practices, including the program of “balanced literacy.” The report advises teachers to “call for the removal of low-quality curricula from classrooms, such as those based in balanced literacy …”) As Nellie Bowles writes:

Mississippi now has the best standardized test scores for fourth graders, when adjusted for demographics (i.e., taking into account socioeconomic status, native language, race, whether your parents raised you to have enough self-esteem, ate enough broccoli, etc.). The rise follows a 2013 decision to use phonics-based learning statewide and to hold back third graders who failed to pass a reading test …

As I mentioned earlier, in Alexandria, Virginia public schools the Standards of Learning test pass rates in reading actually went down last year compared to the year before, even after a return to in-person learning. Yet our local school board’s policy is to continue to devote significant amounts of classroom time to things like “social, emotional, and academic learning (SEAL)” programs that I wrote about in a previous essay, which takes limited school time away from things like boosting reading skills.

Finally, as Crabill points out:

If there is any magic taking place in public education, it doesn’t happen in the administrative offices or even in school board meetings — it’s happening in the classroom through the connection between the educator and the learner. Therefore, school systems must constantly be obsessed with how they can increase the magic taking place in each classroom. There are a few ways to go about this, and they center on doing one of the following: Increasing the quality of instruction that students are experiencing. Increasing the quantity of quality instruction that students are experiencing. If neither of these two variables is increasing, student outcomes are unlikely to improve. Quality and quantity are the two main levers we can pull on … The quality of instruction that teachers provide is the most influential factor to improving student outcomes that school systems control. Teachers are so central to the improvement of student outcomes that any strategy that doesn’t ultimately benefit and support teachers at increasing the quality of instruction their students experience probably will never have an impact on improving student outcomes.

But as we’ve seen in previous essays, where public school teacher collective bargaining agreements are in place, those agreements lock in teacher tenure, regardless of teacher performance.

This concludes this essay series on local school boards.

Paul, I see this is depressingly personal for you. This is your horrible school board in your horrible school district. So what are you planning to do? What should any of us do? This has been a really eye-opening series (as is generally the case with what you write) but I think an increasing number of us want to DO something besides cry in our beer. Seems really tough, which is probably the whole point. So wondering about how you are taking this on. Thanks.