Are School Boards Listening to Anyone?

You might think they’re not listening to you. But they might just not be listening.

Lots of people think school boards aren’t listening to certain groups of their constituents. But the bigger question is whether or not school board members are listening to, well, anyone.

I’ve made it a hobby of mine to watch local school board meetings since the beginning of the year. I’ve been struck by several things.

First, the new school board spent no time at all during its first many months discussing anything having to do with subjects on instructional methods. That is, there was no discussion at all of how kids might learn actual subject matter more effectively, and this at a time when learning losses from restrictive COVID-related school access policies are increasingly clear. As reported in the New York Times:

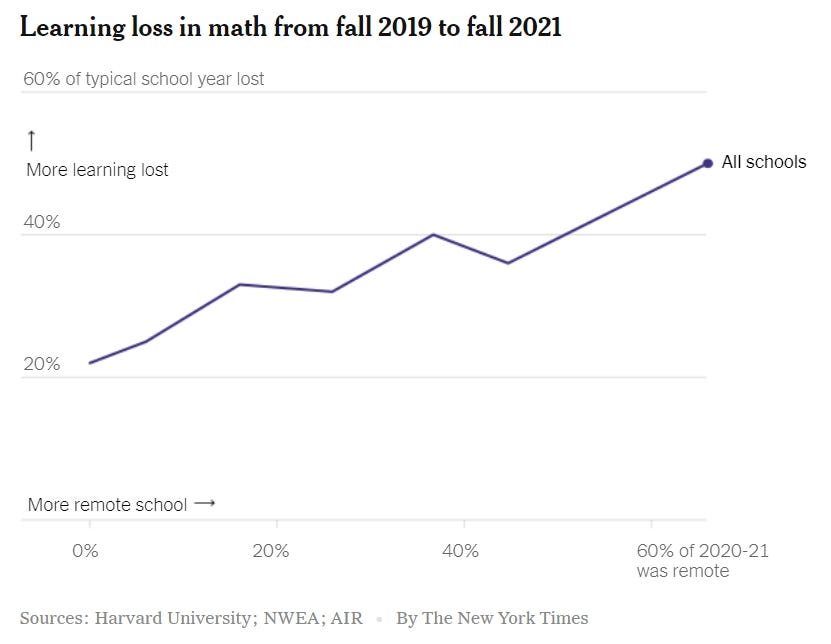

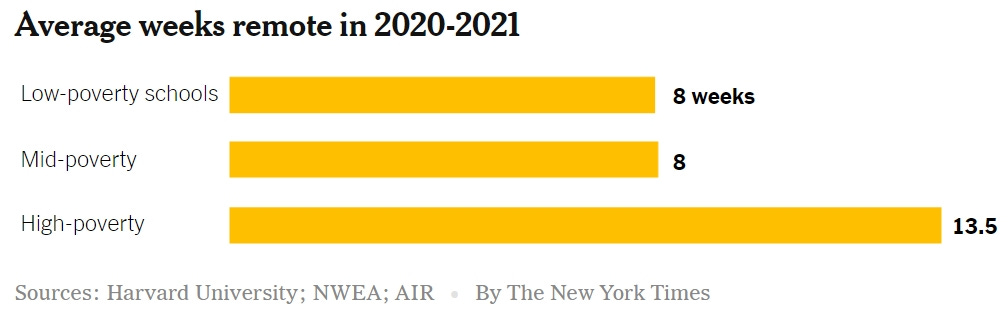

Three times a year, millions of K-12 students in the U.S. take a test known as the MAP that measures their skills in math and reading. A team of researchers at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research have used the MAP’s results to study learning during a two-year period starting in the fall of 2019, before the pandemic began. The researchers broke the students into different groups based on how much time they had spent attending in-person school during 2020-21 — the academic year with the most variation in whether schools were open. On average, students who attended in-person school for nearly all of 2020-21 lost about 20 percent worth of a typical school year’s math learning during the study’s two-year window … But students who stayed home for most of 2020-21 fared much worse. On average, they lost the equivalent of about 50 percent of a typical school year’s math learning during the study’s two-year window … One of the most alarming findings is that school closures widened both economic and racial inequality in learning … [I]n the U.S. during the 1990s and early 2000s: Math and reading skills improved, especially for Black and Latino students. The Covid closures have reversed much of that progress, at least for now. Low-income students, as well as Black and Latino students, fell further behind over the past two years, relative to students who are high-income, white or Asian. “This will probably be the largest increase in educational inequity in a generation,” Thomas Kane, an author of the Harvard study, told me.

There are two main reasons. First, schools with large numbers of poor students were more likely to go remote. Why? Many of these schools are in major cities, which tend to be run by Democratic officials, and Republicans were generally quicker to reopen schools. High-poverty schools are also more likely to have unionized teachers, and some unions lobbied for remote schooling …

Were many of these problems avoidable? The evidence suggests that they were. Extended school closures appear to have done much more harm than good, and many school administrators probably could have recognized as much by the fall of 2020. In places where schools reopened that summer and fall, the spread of Covid was not noticeably worse than in places where schools remained closed. Schools also reopened in parts of Europe without seeming to spark outbreaks … Hundreds of other districts, especially in liberal communities, instead kept schools closed for a year or more. Officials said they were doing so to protect children and especially the most vulnerable children. The effect, however, was often the opposite.

I went to a forum hosted by two of my local school board members and confirmed from each of them that the broad subject of educational methods simply had not been addressed at any local school board meetings to date. This, despite the distribution at a May, 2022, school board retreat of a document stating “Effective school boards are accountability driven, spending less time on operational issues and more time focused on policies to improve student achievement,” and that “it may be helpful to review some of the descriptions of ineffective boards mentioned in the research [namely, school boards that are] [o]nly vaguely aware of school improvement initiatives, and seldom able to describe actions being taken to improve student learning [and] [f]ocused on external pressures as the main reasons for lack of student success, such as poverty, lack of parental support, societal factors, or lack of motivation.” There are hours and hours of discussions at the school board of things like how exactly a “task force” to recommend something about the presence of police in schools will be composed, vague descriptions of the tens of millions of COVID-related federal funds the school system has yet to use, and various “equity audits,” but nothing on pedagogy and how at-risk kids might learn more. (Wherever you live, you might want to perform the following experiment to get a sense of how your own local school board is operating: find the web page that contains archived school board meetings. Click on a few, watching five- or ten-minute clips at random portions of the meetings, and then see for yourself how well the school boards are addressing topics you think are most important.)

Even before various COVID-related restrictions on school access went into effect, a 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress High School Transcript Study, found that while students were taking more rigorous classes in science and math, and getting better grades in those classes, they actually ended up knowing less about those subjects than students did a decade earlier. As Frederick Hess reported:

During the decade between 2009 and 2019, the share of 12th graders who took a rigorous or moderately rigorous slate of courses rose from 60 to 63 percent, and the average GPA of high school graduates climbed from a 3.0 to a 3.11—an all-time high. So far, so good. When we turn to how 12th graders actually fared on NAEP (the “nation’s report card”), though, we see that science scores stayed the same and that math scores actually fell by about 3 percent. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen counterintuitive results like these. In 2009, Mark Schneider, now the commissioner of the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, found that decades of efforts to boost the number of students taking higher-level math classes had led to the dilution of those very classes. In particular, Schneider noted that, between 1990 and 2005, average math GPAs rose, as did the average number of math credits completed by high-school graduates. Furthermore, while only one-third of students completed algebra II in 1978, more than half did in 2008. And yet, despite all of this, NAEP scores for students in algebra I, geometry, and algebra II declined between 1978 and 2008. In other words, more students were taking more advanced math and getting better grades—and yet our students knew less in 2008 than they did 30 years earlier. Schneider termed this phenomenon the “delusion of rigor” though it could equally well could be termed the “dilution of rigor.”

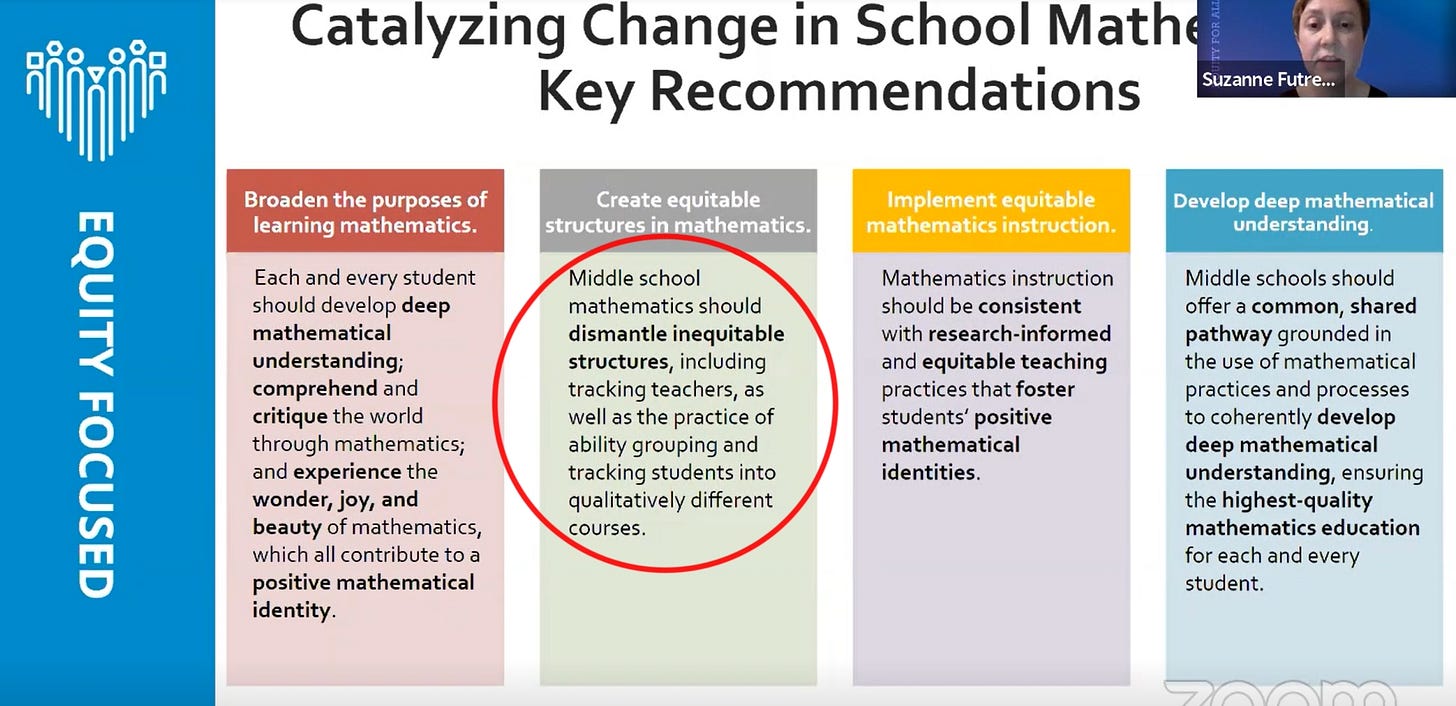

Yet today, not only is our local school board entirely avoiding the question of educational methods and their results, it’s apparently considering eliminating advanced math classes. I say “apparently” because there seems to be some confusion about the proposal. At a May school board meeting, there was discussion of “Middle School Project Mathematics Pathways.” That presentation to the school board featured an official essentially reading the text of Powerpoint slides to the board about the project. One of those slides stated that a “Key Recommendation” of the program was that “Middle school mathematics should dismantle inequitable structures, including … the practice of ability grouping and tracking students into qualitatively different courses.”

I wondered what that actually meant. During the question and answer period that followed this presentation, no school board member asked for any clarification, so I asked two of my district school board representatives what the proposal actually meant (only ⁷one of the two representatives responded), and the result was the following Twitter exchange:

Having watched many of these school board meetings, it seems that few school board members are even listening to the presentations made to them, or if they are, they’re not bothering to seek clarifications when statements made to them are unclear. Then again, at other times, when major proposals to the school board appear to be described in terms that are crystal clear, there’s subsequent confusion. Our local school board was recently briefed on an “Early College Program” in which “Cohorts will be selected to reflect ACPS demographics, including 70% students of color.” That seemed to me to be a pretty clear race-based requirement, so I sought some clarification:

Is it race-based? Yes. Is it a requirement? Well, maybe it’s just a “target.” And what’s the difference between a requirement and a target? Who knows? But the bigger question is, does anyone on the school board even want to know, or would they rather just “go with the flow” of whatever’s being told to them by whichever school administrators who are in charge of formulating this stuff.

I wrote previously on how Sometimes Lemmings Give You Lemons, which explored some of the evidence on how people have a tendency to simply conform to the opinions being expressed around them by others. Since then I was listening to a Great Courses lecture series called Redefining Reality by Professor Steven Gimbel, in which he presents in Lecture 18 the extreme case of Adolf Eichmann, a lieutenant-colonel in the Nazi SS, who went on trial in 1963. As Professor Gimbel writes:

During World War II, Eichmann had been in charge of transporting millions of people from their places of arrest to concentration camps and death camps. Eichmann’s arrest and trial led many people to ask how someone could have done what he did. The easy answer was that he was a monster, but the trial disabused us of this notion. Multiple psychiatrists assessed Eichmann and testified that he was not only sane, but a normal, pleasant fellow. Observing the trial was the German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt. She realized that the greatest evil can be carried out by people who see themselves as simply following orders without assuming any responsibility for their actions. Arendt famously coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe situations in which we create structures that shield people from the real effects of their actions.

What sort of psychological structures? Professor Gimbel continues:

In 1951, the Polish psychologist Solomon Asch tested the ability of people to act independently. In his experiment, test subjects were seated at a table with seven other supposed subjects—confederates of the experimenters. A researcher then informed the group that the purpose of the study was to examine perception and asked participants to look at two charts placed in the front of the room. One of the charts had a single line on it, while the second had three lines. One of the lines on the second chart was the same height as the line on the first chart, and the test subjects were asked to identify this line. In all cases, the correct answer was plainly obvious. The researcher asked each of the subjects to identify the correct line, always asking the real subject last. For the first three rounds, the confederates gave the correct answer, and the test subject followed. But on the fourth round, the confederates all gave the wrong answer. Of the 18 sets of lines, the confederates intentionally got 6 correct and 12 wrong. Interestingly, three out of four test subjects answered with the faulty majority at least some of the time. And once people started conforming, they were much more likely to continue. The test subjects were interviewed after the experiment and reported some interesting reactions. Of those who answered with the majority, some became convinced that they were wrong and the majority was right; they believed that it was important for them to be right because they did not want to spoil the data for the researcher or because they did not want to stick out. But as Asch wrote, “More disquieting were the reactions of subjects who construed their differences from the majority as a sign of some general deficiency in themselves, which at all costs they must hide. On this basis they desperately tried to merge with the majority, not realizing the longer-range consequences to themselves.” Universally, everyone who participated in the test said that independence was preferable to conformity. Yet most conformed; that is, they acted counter to what they knew to be false and counter to their own values. When Asch expanded the study, he found that the larger the majority, the stronger the pull to conform, but that if even one person dissented before the test subject, the subject was much more likely to also voice his or her view. Asch showed empirically that having someone else agree with you is a powerful tool in making people willing to take a contrary position. But if that person were deserted by the fellow dissenter, conformity followed rapidly and continued even after the deserter left the group.

And that’s pretty much what you get with a school board composed entirely of members of one political party.