School Boards – Part 3

When the American Federation of Teachers union sits on a local school board.

I occasionally make it a project of mine to examine in more detail the workings of various aspects of local government (which tend to get less attention in the news) and since a local school board member is a friend and neighbor, and she works full-time for a the American Federation of Teachers union, I’ve become more familiar with how public sector unions influence local elections. That’s the subject of this essay.

Before we drill down to the local level, however, it’s worth providing some big picture context, starting with this particular school board member’s employer, the American Federation of Teachers.

As Mark Zupan writes in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest, teachers unions began to exercise significant control over education policy starting in 1961:

A watershed strike in 1961 by the newly certified affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) in New York City led to the first major collective bargaining contract for public teachers in the United States. While illegal, the successful work stoppage demonstrated to public teachers nationwide the benefits of forceful collective action. The strike led to substantial improvements in pay, benefits, and working conditions and it established a checkoff for union dues (the checkoff allows the government to automatically withhold a portion of public employees’ salaries to cover union dues and agency fees). Prior to the New York City’s teachers’ strike, only a small number of teachers were members of unions advocating on behalf of their interests. The National Education Association (NEA), established in 1857, promoted professionalism, progressive education, and administrative interests but was largely opposed to teachers unions during its first century of existence. During the decades after the watershed strike, however, union membership and collective bargaining agreements in the United States increased dramatically. By 1993, 80 percent of public K-12 teachers belonged to such interest groups. The percentage of teachers covered by collective bargaining agreements soared from 0 percent in 1960 to 65 percent by 1978, leveling off there since. Along the way, the NEA shifted to a pro-union stance when faced, in the 1960s, with growing competition from the AFT. Now, the NEA represents an estimated 86 percent of all unionized teachers … Beyond unionization, the monopoly power on the supply side of K-12 public education has grown through school district consolidation. Between 1950 and 1980, the number of districts declined by 81 percent, from 83,642, to 15,987. This trend has been driven by an increase in urbanization in which process several trends are occurring, for example, increased pressure to take advantage of economies of scale; heightened importance of state aid aiming to reduce any cross-district differences in quality; and teachers unions seeking to lower their organizational costs and increase their political influence. As public school districts have consolidated, the potential diminishes for citizens to hold officials accountable by voting with their feet if they are unhappy with the services provided. By looking across US school districts, economist Caroline Hoxby shows that the lower competition brought about by district consolidation has its effect in lower student academic achievement and increased per-pupil spending.

An example of teachers unions’ influence on education is the Rochester Teachers Association, a union that was led for thirty-five years by Adam Urbanski, who is now vice president of the American Federation of Teachers union. As Zupan writes:

At the city level, nothing better demonstrates government insiders subverting the public interest than the Rochester Unified School District. When it comes to total expenditures and employment at the state and local government level, education is by far the largest category. For the school year from 2012 to 2013, the current expenditure per public elementary and secondary pupil was $20,333 in Rochester versus $19,552 for New York State and $10,705 for the United States overall. When one adds in capital and interest payments, the amount Rochester public schools spent per student during that same period ($23,937) exceeded the annual tuition charged by top area private schools, which cost between $10,000 and $20,000 depending on whether they are religious-based or not … [T]he district’s budget grew by more than 15 percent, from $694 million to $802 million, over the period from 2011 to 2016 while during the same time frame K-12 enrollments declined by over 10 percent, from 30,734 to 27,604 students. The student outcomes associated with such largesse in public school spending have been mediocre at best. Only 51 percent of Rochester’s public high school students graduate in four years; this rate is one of the lowest rates in the country … The city’s poor educational outcomes have contributed to Rochester’s population shrinking by a third since 1960. The population exodus, as citizens have voted with their feet and moved to locations with better returns on educational investment, has diminished the city’s tax base, downtown, sustainability, and sense of community while increasing sprawl and commutes.

Adam Urbanski is now one of the bosses of our local school board member who works for the AFT.

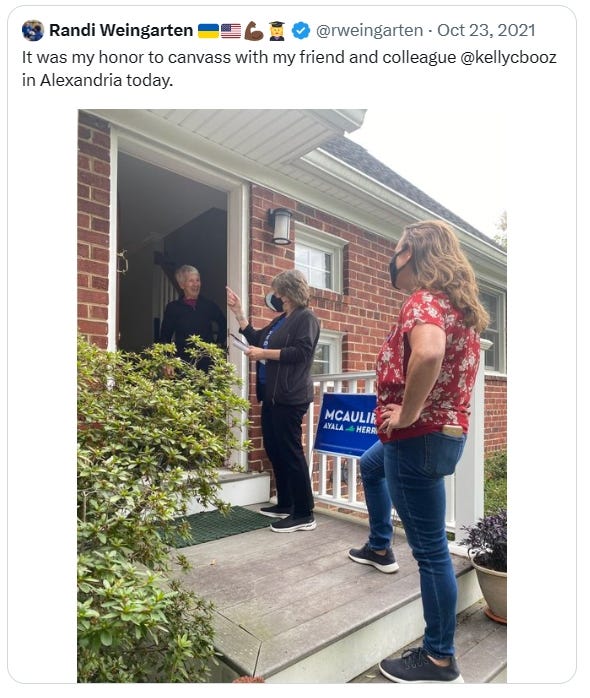

As Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions, teachers unions “run members as candidates, for example, to local school boards,” and that’s just what happened in this case, with AFT president Randi Weingarten herself appearing at a campaign event for her school board candidate employee:

(Posting these pictures from Twitter, I just noticed the last picture features a campaign sign for Terry McAuliffe, who ran against Glenn Youngkin for Governor of Virginia in 2021. The day before the election, McAuliffe had Randi Weingarten share center stage with him at a campaign rally. Youngkin won in a surprise upset, which many attribute to McAuliffe’s close ties to Weingarten and the teachers unions.)

Ms. Booz ended up winning a spot on the school board in a typical low-turnout election in which teachers union volunteers were likely the most numerous campaign participants. (Indeed, Mr. Booz touted her support from a group called The Alexandria Political Action Committee for Education (APACE), which turns out to be a teachers union.)

Now, having a full-time paid employee of a teachers union on a school board -- when, as the AFT states, “The AFT passes resolutions on a wide range of issues that affect members in our different membership constituencies and that address other national and international issues of importance to the union and to our vision for the country” -- would seem to constitute a clear conflict of interest, especially in a school district that’s in the process of setting up collective bargaining with public school teachers unions (and which, probably not coincidentally, just elected Ms. Booz vice-chair of the board on a bare majority 5-4 vote). Indeed, the Code of Ethics for the City of Alexandria’s school board provides that school board members “Put loyalty to the welfare of the children and to the School Division as a whole above loyalty to individuals, voting districts, particular schools or other special interest groups.” But as I’ve written previously, teachers unions have a legal fiduciary duty to exclusively promote the interests of union members, not students, which creates an inherent conflict of interest. I asked Ms. Booz about this issue (but received no response):

The recent move in Virginia to teacher collective bargaining will of course increase costs. As John Tillman explains in the Wall Street Journal:

Take Loudoun County, where the school board has approved collective bargaining, allocating an extra $3.3 million to hire 13 new administrators specifically for union-related work in 2024. That’s before the additional cost of a coming teachers union contract. In nearby Alexandria, setting up union negotiations is expected to cost taxpayers up to $1 million, while the General Assembly’s Commission on Local Government predicts the city’s eventual union contracts will cost $25 million annually. Fairfax County is forecasting at least $1.6 million in administrative costs, with forthcoming union contracts likely costing tens of millions more per year. Prince George County, south of Richmond, foresees the annual cost of contracts at $10 million, with one local official saying the higher costs will run “forever.” In Richmond itself, public-school employees and principals have already unionized, with teachers ratifying a pricey contract in December. The costs will grow as unions make more demands, and inevitably unions will demand higher state taxes as well as local levies to fund the largesse. Money isn’t the only thing taxpayers are losing. They’re also losing control over their local governments and schools. When agencies and educators unionize, the average person can’t simply petition elected officials to intervene if there’s a problem, because a collective-bargaining agreement binds officials’ hands. If a teacher is failing his students, the union protects him. If a police officer is targeting or neglecting a specific part of town, the union covers for him. This is the proven path to government that’s less responsive and more costly. Naturally, Virginia’s public-employee unions have no intention of letting go of their growing power. They have opened the floodgates of political spending. The Virginia Education Association, the state’s largest teachers union, increased its political contributions 11-fold between 2020 and 2022. Every cent in 2022 went to Democrats. Unions hope to elect Democrats who will reward them with even better contracts. As unions gain more members, they’ll get more dues money to spend electing friendly politicians. It’s a cycle that benefits everyone but Virginians. Gov. Youngkin knows the immense danger facing his state. He’s made repealing the 2020 collective-bargaining law a priority, yet with slim Republican control in the House of Delegates and a Democratic majority in the Senate, he couldn’t make headway over the past two years. That would change if Republicans took full control of the General Assembly. Both the GOP and unions have launched massive get-out-the-vote efforts, with a particular focus on early and absentee voting. Victory will likely come down to which side turns out the most voters before Election Day. If Republicans fall short, it will get harder to repeal public-sector collective bargaining, since unions will become more powerful with every passing year. It may be now or never to stop Virginia from becoming a wholly owned union subsidiary like Illinois.

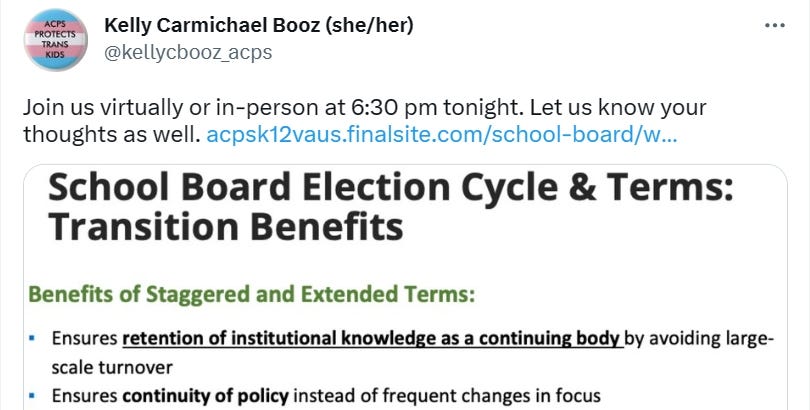

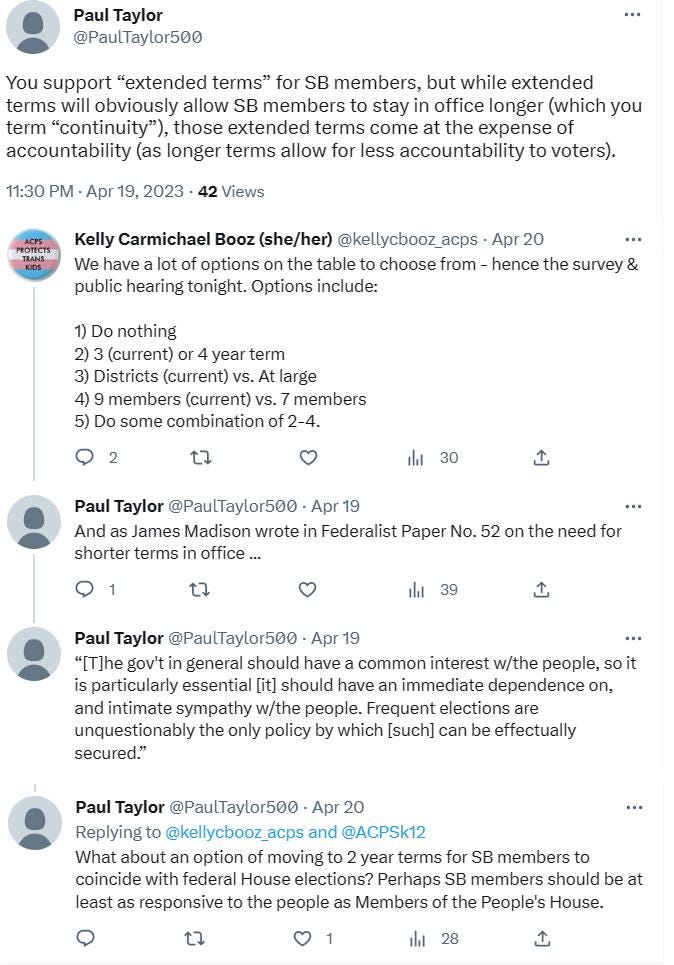

Also, now that our local school district is creating collective bargaining for public sector employees, the same AFT-employed school board member is taking the lead in promoting longer and staggered terms for board members for the explicit purpose of promoting “continuity of policy” to lock in certain policy positions over longer periods of time. Again, I asked Ms. Booz some questions about that proposal, but received no response:

Of course, if this school board member who works for the AFT succeeds in getting longer school board member terms, and is reelected (as the vast majority of union-backed school board candidates are), she’ll be secure in her school board seat despite any ethical conflicts of interest to the contrary under the school system’s new public sector collective bargaining regime, as there are no enforcement provisions attached to ethics code violations.

When it comes to the size (and therefore the potential influence) of unions, as Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

It is worth emphasizing, however, that precise data on the levels of union membership and the prevalence of collective bargaining are surprisingly difficult to come by. Even the simplest questions must often be answered through sketchy information that is patched together from various data sources. The Department of Education, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Census Bureau, and other standard sources of information have done a poor job of collecting data on teachers unions and collective bargaining. This is unfortunate. The teachers unions represent the government's own workers, they engage in collective bargaining with the government's own agencies, and they are integral components of the modern American public school system. Just as the government collects data on the public schools, so it should also collect basic, factual information about the teachers unions. For each school district, at a minimum, it should be a matter of public record which union (if any) has bargaining rights for teachers, what the collective bargaining contract contains, how many teachers belong to the union, and how many do not. This information should be gathered regularly, just as school data are, and kept in national databases that are readily available to researchers, public officials, parents, and other citizens.

But regarding the AFT in particular, another unique conflict of interest arises when AFT employees serve on school boards, namely issues that surround the proliferation of administrative (non-teaching) positions in school systems. As Terry Moe writes:

The AFT has expanded from some 59,000 members in 1960 to 1.4 million members in 2010. Part of this expansion, obviously, is due to its success in organizing classroom teachers. Yet it has also been actively involved over the years in organizing “classified” workers: secretaries, janitors, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and other district employees. It also organizes, by its own account, “paraprofessionals …; higher education faculty and professional staff; federal, state, and local government employees; …nurses and other health care professionals…[and, in addition] approximately 80,000 early childhood educators and nearly 250,000 retiree members. The NEA [the National Association of Teachers, another national teachers union] is up-front about how many teachers and nonteachers it organizes and how many of its teachers are currently practicing. The AFT is not up-front about any of this. The fact is, no one outside the AFT knows the exact breakdown of its membership. The union goes out of its way to publicize the total size of its membership—especially now that it has passed the symbolic million mark — but it keeps the actual number of teacher members hidden. This being so, I requested accurate data on teacher membership from AFT headquarters in Washington, D.C. Its leaders refused to provide them. Indeed, they told their state affiliates not to provide me with any membership data either. The AFT is a teachers union that literally will not say how many teachers it represents … [W]hile the NEA is 2.3 times larger than the AFT in total membership, its dominance in the organization of practicing teachers is far greater than that. The AFT is only as big as it is because it organizes so many nonteachers and because it shares so many members with the NEA.

That the AFT is largely composed of non-teachers shows its keen interest in non-teaching positions. This can work at cross-purposes to teachers when it comes to the availability of funds to pay for more teachers, or to pay teachers more. For example, as Zupan writes: “In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), 45 percent of payroll expenses go toward employees who do not interact with students in the classroom ($2.1 billion per year out of $4.7 billion) and the pay of administrators and centralized staff exceeds that of teachers.”

Where I live, two local school board members had a question and answer session at a local park in June, 2023. One teacher remarked on the administrative bloat in the local school system, and said, “Make sure the [central office] is auditing themselves. They don’t need all that space, they don’t need all those consultants, they don’t need all those administrative assistants.” But all those administrative assistants, and more that could added to the payroll in the future, are potential AFT union members.

And indeed, as I’ve written previously, this AFT-employed local school board member promoted the hiring of a new “restorative practices coordinator” to “coordinate” something called restorative practices and discussion circles. (It’s the official policy of the American Federation of Teachers to “place restorative justice coordinators/trainers and support staff in every school,” regardless of whether teachers find them worthwhile or not.) At the prodding of the AFT-employed school board member, the board brought the separate restorative practices coordinator position up for a vote, with an annual salary of $159,000 (which, school board members were told, would reduce the school’s ability to fill current staff vacancies), even though the school superintendent repeatedly told the board: “Our staff, we have a wish list and we have a need list, and this [the creation of a “restorative practices coordinator] isn’t even on the wish list. So I’m just trying to understand how I go back and justify why we now are going to do something that they didn’t even ask for. So I’m hoping I can walk away with something to share to say this is why we are going to add that, staff, you know. Not they just added it. I want to have an explanation as to why it’s being added so I can explain it to everyone.” (See at the 1:11:23 minute mark here.) The superintendent received no subsequent response to that request, and the board discussion meandered on to other topics after the board chair said “We’re going to have to move on.” By the end of the school board meeting, the board ultimately failed to approve the creation of that position when it couldn’t agree on what money to cut from the budget to pay for it, at least for now.

As I described in a previous essay, the underlying program of “restorative practice,” is a program “in which school suspensions of disruptive students are reduced in favor of ‘discussion circles’ in which perpetrators and victims discuss their feelings, in order to reduce disparate racial impacts in suspensions. Such programs are unpopular among educators themselves, as was found by an extensive survey by the RAND Corporation (see Table 3), but are promoted by certain interest groups nevertheless,” including the American Federation of Teachers, because of their political alliance with the Democratic party and its policies on race. Again, as I wrote previously:

The first randomized control trial study of “restorative justice” in a major urban district, Pittsburg Public Schools, was published by the RAND Corporation. The results were notable. While the teachers surveyed reported improved school safety, professional environment, and classroom management ability, those teachers knew their supervisors who were supporting the programs would be reading the survey results. Interestingly, the researchers then interviewed the students in those classrooms separately, and found that students disagreed, thinking their teachers’ classroom management deteriorated, and that students in class were less respectful and supportive of each other, and they reported bullying and more instructional time lost to disruption. “Restorative justice” also had no impact on student arrests. The most troubling finding was that there were significant and substantial negative effects on math achievement for middle school students, black students, and students in schools that are predominantly black. Summaries of the results of other studies of “restorative practices” programs can be found here and here … If disruptive students are allowed to remain in class, all other students have their learning disrupted, including minority students. Researchers have found that children who were exposed to an above-average (within-school) concentration of disruptive peers in elementary school have much lower-than-predicted future earnings. They predict that adding one disruptive peer to a class of 25 will result in earnings reductions of over 3 percent.

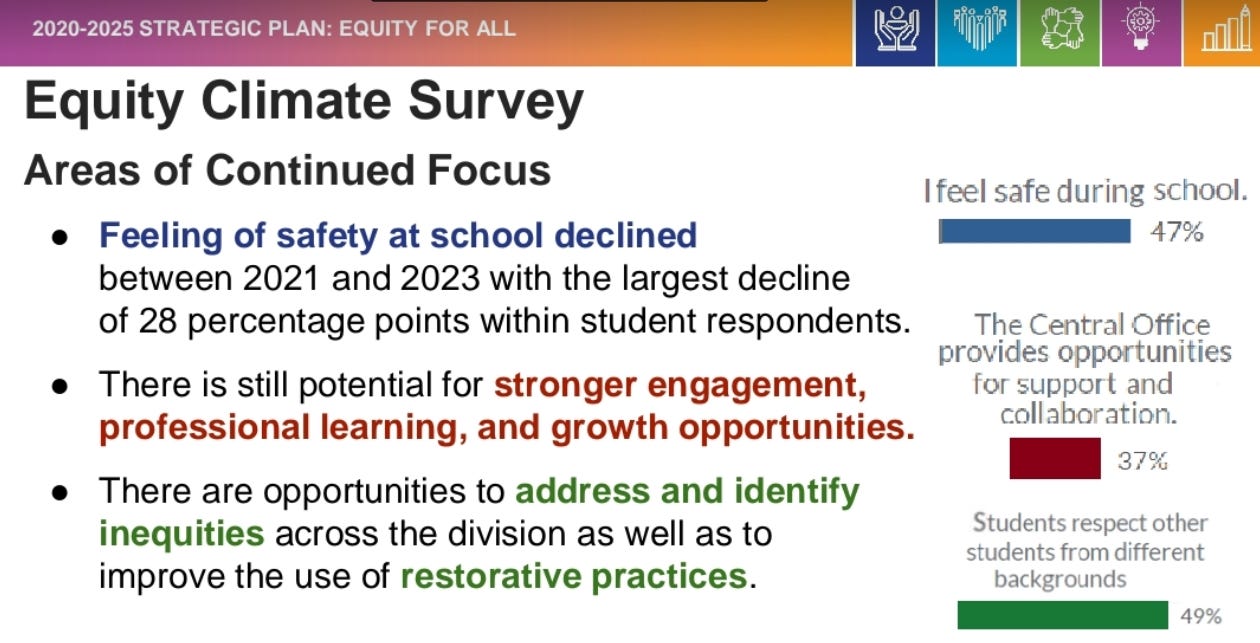

Yet, at our local school board, increased reports by students of feeling unsafe in school is met with plans to boost the use of “restorative practices,” as a slide used in a recent school board presentation makes clear:

The increased class disruptions caused by the lax discipline policies under a “restorative practices” approach no doubt contributes significantly to teacher burnout. I was visiting my dad in Connecticut last October and happened to see on the local news a story about a survey of Connecticut public school teachers in which 64 percent of teachers surveyed said that “Problems with student discipline/student behavior” was a “very serious concern.” As Howard writes, “Good teachers quit because of the dispiriting cultures of their schools.” And my understanding is that lax school discipline policies — and the resulting inability of teachers to command their classrooms amidst a significant portion of disruptive students — is a main reason that young teachers are leaving the teaching profession.

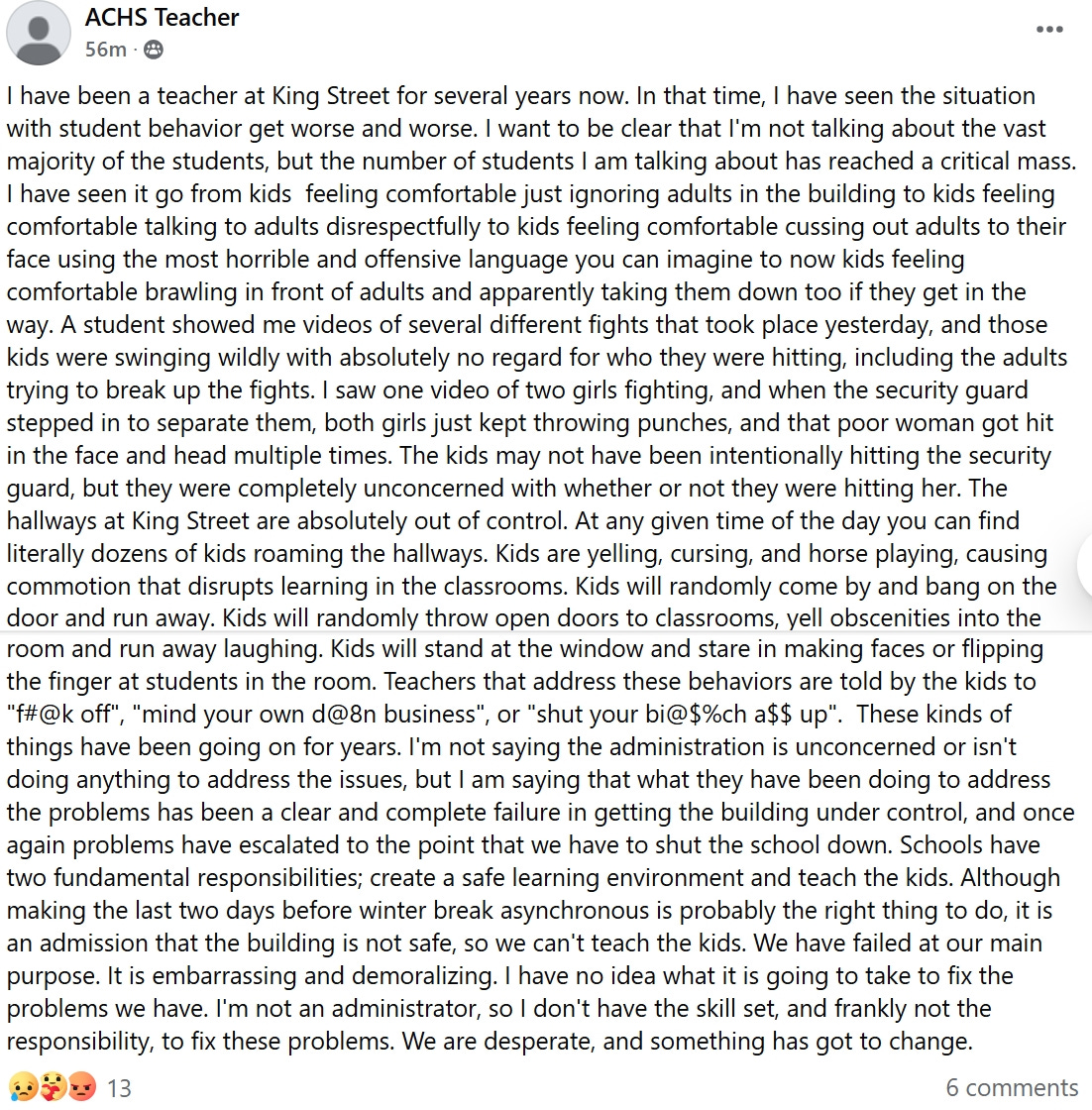

After a day of disruptive fighting among students at our local high school in Alexandria, Virginia, the school had to resort to “remote learning” for the next couple of days, resulting in one teacher there posting the following anonymously on Facebook:

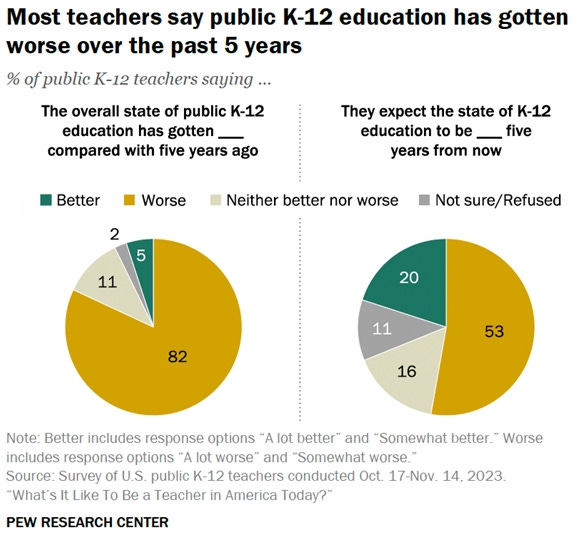

A 2024 Pew Research survey of 2,531 U.S. public K-12 teachers found that nearly half the teachers say students at their school have poor academic performance and behavior, and 80% believe schools have gotten worse over the last five years. About eight in ten teachers said the lasting impact of pandemic closures on students’ behavior, academic performance, and emotional well-being has been very or somewhat negative, and half of teachers said chronic absenteeism among their students is a major post-pandemic problem and persistent, and 82% said the overall state of public K-12 education has gotten worse in the past five years. About two-thirds of teachers (66%) said that the current discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat mild, while only 2% said the discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat harsh. Most teachers (67%) said teachers themselves don’t have enough influence in determining discipline practices at their school.

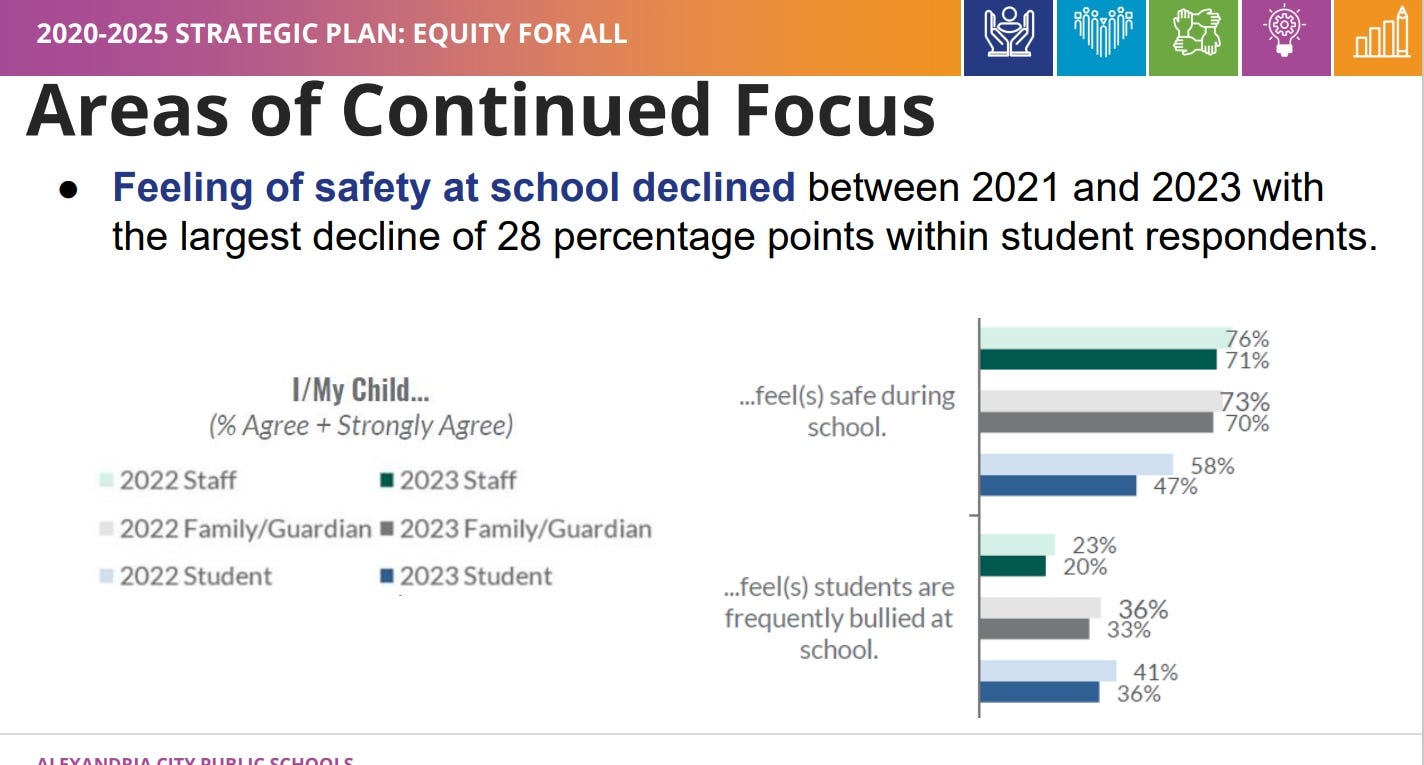

Finally, I recently became aware that there was a lack of transparency regarding something that might be contributing to a “dispiriting culture” at our local public schools as it relates to feelings of physical safety. For several years, the local school system has conducted “Equity Climate Surveys” that ask various questions about students, staff, and parents’ feelings about how safe the schools are. A presentation made to the school board stated “School and division leaders have access to an interactive dashboard, which provides all three years of survey data for all items. Through the dashboard, the data can be further disaggregated by respondent demographics (ex. role, school, grade, race/ethnicity, special populations) or a combination.” I asked a local school board member if the public would have access to the same dashboard. It turned out that not only did the public not have access to it, but neither did school board members. As I looked through the presentation on the survey that was given to the board, I noticed this slide:

The slide notes that the “Feeling of safety at school declined’ in the most recent survey, but those results were not broken down by race. Coincidentally, back in January, 2023, I was part of a focus group organized by a consulting group the school system hired to get people’s thoughts on school safety. During the focus group, the fact that the school had conducted its latest “Equity Climate Survey” was mentioned. After the focus group was over, I emailed the consultant who moderated the focus group and asked “I had one question I was wondering if you could answer: Regarding the survey that was conducted, what percentage of black and Hispanic students attending ACPS [the local school system] reported they didn't feel safe at school?” I asked because while I understood the school board supported the “restorative practices” approach to school discipline (which was intended to help minority students by reducing their suspension rates), I was wondering whether such a relatively lax discipline policy might also be leading to more fights that disproportionately impacted minority students. The consultant was kind enough to respond with an email stating she wish she could share the entire report, but she did receive permission to send me some disaggregated findings, including that “Overall, about two-thirds of respondents report feeling safe; however, POC [people of color] and multiracial respondents less frequently agree to school safety items compared to their White peers. Notably, POC and multiracial respondents less frequently agree that they feel safe going to and from home and school, at school-sponsored events, and at school.” Those more detailed findings, and all the other disaggregated data in the surveys, should of course be made public, so progress (or regression) on any particular school policy can be gauged.

Incidentally, school safety data presented to the local school board in September, 2023, showed significant rises in violent incidents at the local public schools:

As Jason Riley writes in the Wall Street Journal:

A professor at an academic conference I attended earlier this month noted that “antiracism” and the policies that flow from it are a much bigger problem today than racism itself. Some might dismiss that observation as hyperbole, but examples keep piling up. Living-wage mandates price poor minorities who are desperate for employment out of jobs. Bail-reform measures make bad neighborhoods even more dangerous by going easy on repeat offenders. Affirmative-action admissions policies in higher education boost dropout rates by mismatching black students with schools in the name of diversity. Open-space zoning laws, supported by environmental zealots, have limited the construction of affordable homes and thereby decimated the black population of major cities, such as San Francisco. It’s a long and depressing list. Learning losses experienced by students during the pandemic, and especially by low-income minorities, have been attributed to an excess of remote schooling that was driven by union demands more than sound science. A study released last week by the U.S. Education Department offers reason to believe that policies being advanced by the equity crowd may be contributing to the challenge of getting our youngsters back up to speed academically. According to an annual survey of school leaders conducted by the federal Institute for Education Sciences, schools saw a 56% increase in “classroom disruptions from student misconduct” compared with a typical school year before the pandemic. There’s also been a 49% rise in “rowdiness outside of the classroom,” in places such as cafeterias or hallways. Actual “physical attacks or fights between students” are up by one-third, and threats of the same have increased 36%. Whatever the impact of pandemic education protocols on this behavior, student suspension policies pushed by the political left are no doubt making matters worse. Under President Obama, the Education Department released a study showing that black students are suspended from school at higher rates than white students and concluded that the only possible reason for the disparity was racism. Similar studies have shown that whites are suspended at higher rates than Asians, but progressives stop reading after they find the statistic that fits their preferred narrative. Thus, the administration subsequently issued letters of guidance to school districts that said federal officials would consider higher school-discipline rates among blacks to be evidence of racial discrimination. The response, predictably, was a reduction in suspensions, which led to more disruption and bullying and to students feeling less safe—especially black students. A federal survey from 2017 found that 37% of black students nationwide reported being bullied, the highest percentage of any racial or ethnic group. A policy intended to fight racism wound up harming black kids the most. Equity strikes again! The Trump administration revoked the Obama-era guidance, but the pandemic made the matter moot until students began returning to the classroom again. President Biden, meanwhile, has pushed to reimplement the Obama policy … The likely problem isn’t that school discipline policies are too harsh but that they’re too lax. Better to teach children to behave before they leave school and face far harsher consequences for making bad decisions as adults. Charter schools, which enroll a disproportionate number of low-income black and Hispanic children, have been criticized for employing stricter discipline policies for troublemakers. Yet academic studies have shown that charter students were less likely than their peers in traditional public schools to be incarcerated later in life.

As reported by the Fordham Institute:

[W]hen one working paper from the University of Arkansas attempted to isolate the causal relationship—comparing suspended students to “otherwise similar” students—they found a positive relationship between suspension and grades. Similar behaviors caused both poor grades and suspensions; suspensions did not cause poor grades. Shooting spitballs and whispering to classmates are bad for both grades and behavior records. The researchers still find other reasons to justify the reduction of suspensions but suggest that we “should not expect academic gains to follow.” Regarding the disparate rates of punishment between Black and White students, it’s necessary to compare the effects of suspensions to the unintended consequences of their removal. If the side-effects are worse than the disease, we need to find another cure. There are district-wide case studies that provide useful insight. Philadelphia rolled back their use of suspensions in 2012–13, and the findings from one academic review are concerning. Reading and math scores plummeted, truancy increased, and the occurrences of violent crime spiked. Ironically, students ended up spending more time suspended because they received fewer suspensions but for worse infractions, thereby garnering longer punishments. Similar results arose in New York and California. Another study followed the results of quarterly achievement tests in both math and English and compared them to suspensions in the school. It concluded that suspensions improved math scores for non-suspended students. In a simple pro-con analysis, Amber Northern, senior vice president for research here at the Fordham Institute, summarized the results: “The aggregate positive effects of peer suspension on non-suspended peers could well be greater than the aggregate negative effects on suspended students.” Perhaps these dismal showings only occur when suspensions are banned without replacement with another system. One randomized-controlled trial from the RAND Corporation stymies that contention. With the implementation of restorative justice practices, disparities in suspension rates did, in fact, drop. Alongside that, however, came an uptick in misbehavior, classroom disruption, and bullying. I’ve taught in such a building. Suspensions rates dropped, but only because teachers stopped reporting behavior. If anything, as the study implies, behavior worsened.

And following a school shooting in 2023, Max Eden wrote:

Unfortunately, the recent shooting is all too easy to understand. Teachers put their finger on a root cause quickly. At a school board meeting shortly after, teachers inveighed against the school board for its lenient school discipline policies. “It was just a matter of time before something like this happened,” one teacher said. “Teachers often joke about how students get sent into the office for discipline and come back ten minutes later with a snack and pat on the back.”

At the June, 2023, question and answer session with two local school board members I mentioned previously, one teacher, remarking on the isolation of the school board from on-the-ground realities at schools, said “Please come hang out with me whenever you want. Meet my students. Break up a fight. See what we do every day.” Another teacher at the same meeting remarked that young, new teachers “coming out from college level, there really aren’t that many reinforcements coming, simply because teachers are not being paid enough and they don’t want to deal with the student behaviors …”

In the next essay in this series, I’ll look at advice given by a former school board member in Texas, and explore how it relates to the performance of our local school board here in Alexandria, Virginia.

Paul, I cannot wait to read the next installment. This seems horribly bad. It seems prima facie obvious. Yet no one seems to be doing anything. At what point do people either rise up and vote with their feet (e.g., private, home school, whatever), vote with their votes (rare but happens) or do something I haven't yet imagined. It all seems so entrenched and therefor hopeless, but not everything can be hopeless. Thanks.