Restorative Malpractices

Have you heard of “restorative practices” at your school?

As described in a previous essay, due to the dramatic rise in the number of administrators who issue new rules in schools, teachers today spend a lot more time trying to comply with those rules than instructing students with their own lesson plans. In many school districts, yet another pull on teachers’ time is the promotion of programs called “restorative practices” or “restorative justice.” These are programs under the rubric of “social-emotional learning” in which school suspensions of disruptive students are reduced in favor of “discussion circles” in which perpetrators and victims discuss their feelings, in order to reduce disparate racial impacts in suspensions. Such programs are unpopular among educators themselves, as was found by an extensive survey by the RAND Corporation (see Table 3), but are promoted by certain interest groups nevertheless. (Indeed, research over many decades has shown that bad conduct must soon be met with penalties if the bad conduct is to stop. Academic experiments going back to the early 1980’s, executed by political scientist Robert Axelrod, has demonstrated that social cooperation is furthered by a “tit-for-tat” strategy consisting of a combination of being nice initially, but then retaliation for bad conduct, and clear rules. Further, researchers have shown that people have a tendency to exhibit moral hypocrisy, in which they say they will act in a certain fair manner going forward, but when they think no one is looking they revert to acting in a way that furthers their own self-interest.)

The issue of restorative practices came up at a recent local school board meeting, and the debate (or lack thereof) was informative. The subject was whether the school system should hire a new “restorative practices coordinator” at $159,000 a year to, well, “coordinate” restorative practices and discussion circles. The school board voted on approving a separate restorative practices coordinator position, with an annual salary of $159,000 (which, school board members were told, would reduce the school’s ability to fill current staff vacancies), even though the school superintendent repeatedly told the board: “Our staff, we have a wish list and we have a need list, and this [the creation of a “restorative practices coordinator] isn’t even on the wish list. So I’m just trying to understand how I go back and justify why we now are going to do something that they didn’t even ask for. So I’m hoping I can walk away with something to share to say this is why we are going to add that, staff, you know. Not they just added it. I want to have an explanation as to why it’s being added so I can explain it to everyone.” (See at the 1:11:23 minute mark here.)

The superintendent received no subsequent response to that request, and the board discussion meandered on to other topics after the board chair said “We’re going to have to move on.” By the end of the school board meeting, the board ultimately failed to approve the creation of that position when it couldn’t agree on what money to cut from the budget to pay for it, but even so the proposal continued to have the support of three board members, including one who’s currently a full-time employee of the American Federation of Teachers. Notably, it’s the official policy of the American Federation of Teachers to “place restorative justice coordinators/trainers and support staff in every school,” regardless of whether teachers find them worthwhile or not. (As was discussed in a previous essay, teachers unions are actually prohibited by law from “putting students first.”)

The purported purpose of “restorative practices” is to reduce racial disparities in school discipline, often under the false assumption that these disparities are caused by racism. Racial disparities in school discipline rates aren’t due to racism, but to student behavior. Research in the Journal of Criminal Justice found the following:

[W]e examined whether measures of prior problem behavior could account for the differences in suspension between whites and blacks. The results of these analyses were straightforward: The inclusion of a measure of prior problem behavior reduced to statistical insignificance the odds differentials in suspensions between black and white youth. This, our results indicate that odds differentials in suspensions are likely produced by pre-existing behavioral problems of youth that are imported into the classroom, that cause classroom disruptions, and that trigger disciplinary measures by teachers and school officials. Differences in rates of suspension between racial groups thus appear to a function of differences in problem behaviors that emerge early in life, that remain relatively stable over time, and that materialize in the classroom.

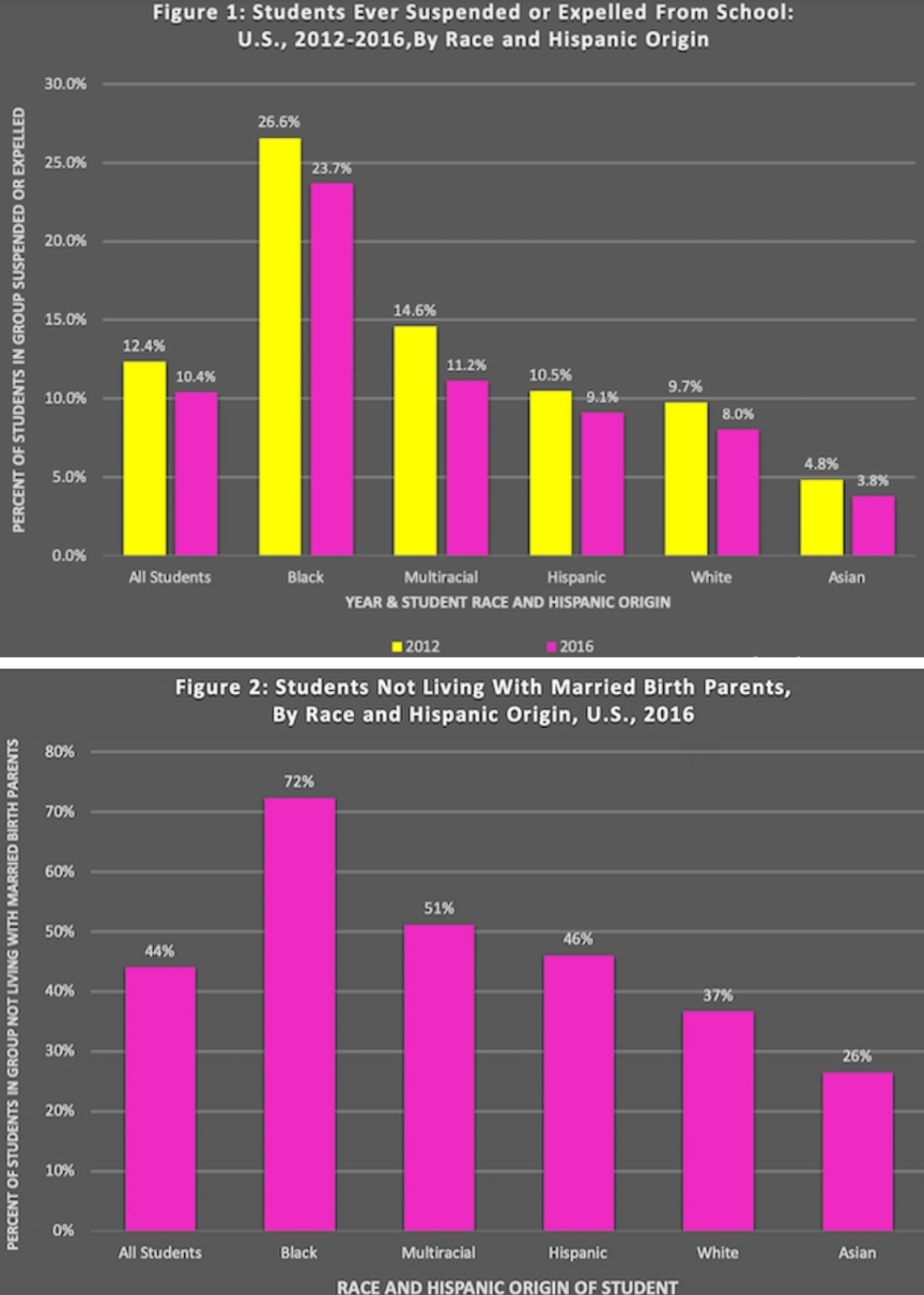

Statistical racial disparities in school discipline also show they follow in large part from racial disparities in family structure. In a 2019 report by the Institute for Family Studies, sociologists Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox, researchers have found that:

controlling for family structure reduces the racial difference in school suspensions by about 55%, whereas controlling for socioeconomic status only reduces it by about 38%. These results, then, suggest that family structure is a signal factor in accounting for real differences in school conduct and school suspensions. This is especially noteworthy because discussions related to racial disparities in school discipline often overlook the role of family structure and highlight socioeconomic explanations.

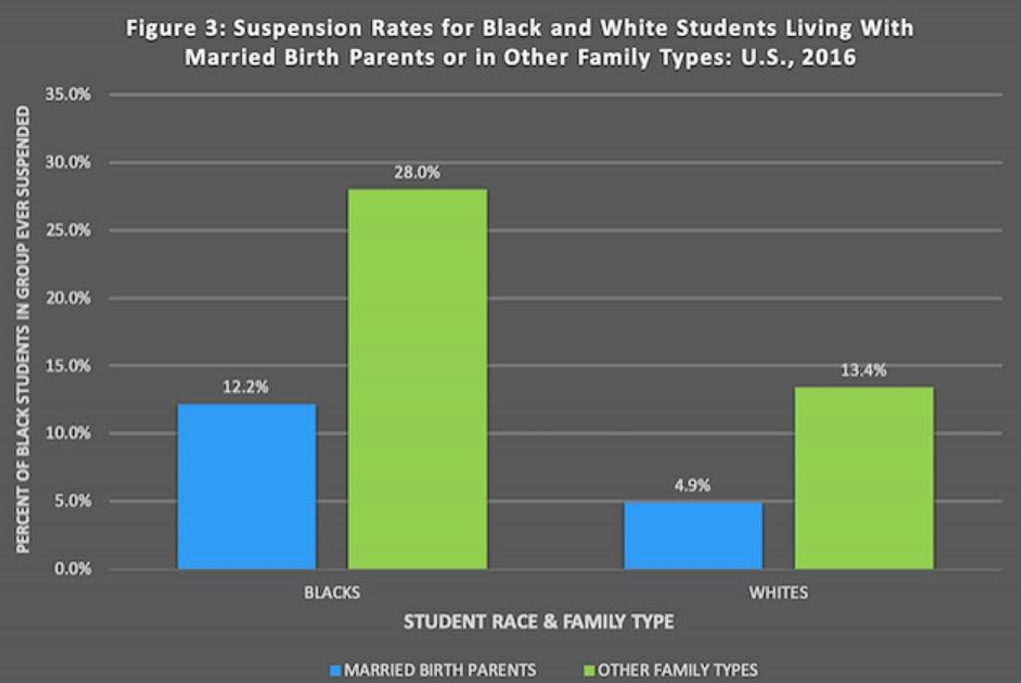

The same report found that black students living with both married parents had suspension rates that not only were less than half as large as those for other blacks, but also less than the suspension rate for white students from families that weren’t intact, indicating that statistical disparities are more likely correlated with the benefits of growing up in two-parent families. As Zill and Willcox report, “among black students who do live with both married birth parents, suspension rates are less than half as large as those for black students living in other family types: 12% versus 28%. The suspension rate for black students living in intact families, 12%, is also less than the suspension rate for white students from non-intact families, 13% (see Figure 3 below).”

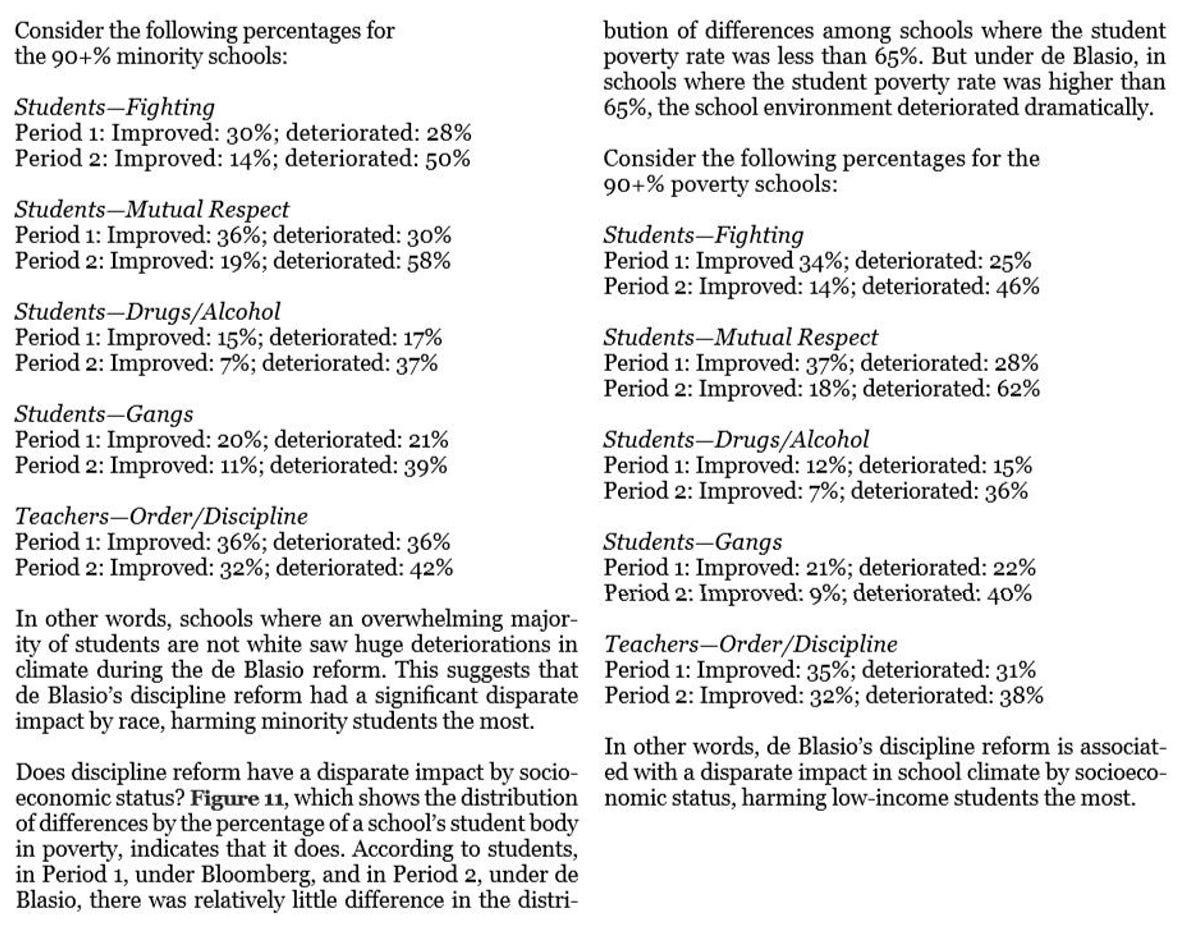

Nevertheless, President Obama issued an executive order creating a commission to investigate schools whose discipline procedures end up affecting minority students in disproportionately larger numbers, causing many school districts to reduce suspensions, with alarming results. The resulting reductions in suspensions in New York City led to the following, based on the city’s own surveys: in terms of violence, 50 percent of schools deteriorated, and only 14 percent of schools improved. In terms of gang activity, 39 percent deteriorated, while only 11 percent of schools improved. For drug and alcohol use, 37 percent deteriorated while only 7 percent of schools improved.

A report by the Heritage Foundation reviewing the academic literature regarding restorative practices programs found as follows:

Prominent researchers and academics such as the Manhattan Institute’s Heather Mac Donald and the University of San Diego’s Gail Heriot (a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights) have cited the U.S. Department of Education’s Indicators of School Crime and Safety to demonstrate that students from different backgrounds do, in fact, exhibit different behaviors and report different levels of school safety. To wit:

· Physical Fights. The Indicators of School Crime and Safety data show that 33 percent of black students in grades nine through 12 reported being in a physical fight in school or outside school in the past year, compared to only 21 percent of white students.

· A figure that MacDonald cited in the 2017 Indicators report remains true for the 2018 edition of the report: The percentage of black students who reported being in a fight on school property was more than double the figure for white students (15 percent versus 6.5 percent).

· Fear for Personal Safety. Nearly twice as many black students (7 percent) reported being “afraid of attack or harm at school” compared to white or Hispanic students (4 percent each).

· Gang Activity. Seventeen percent of black students ages 12–18 reported gangs “were present” at school, compared to 12 percent of Hispanic students and 5 percent of white students.

· Drugs. Nineteen percent of black students and 25 percent of Hispanic students said “illegal drugs were made available to them on school property” in the past year, compared to 18 percent of white students.

Note that students of different races are not evenly distributed across the country. Fifty-eight percent of black students and sixty percent of Hispanic students attend schools in which 75 percent or more of student enrollment is comprised of minority students.

Just 6 percent of white students attend such schools. With a higher percentage of black and Hispanic students living in single-parent homes and/or in poverty concentrated together in majority–minority schools, policymakers must evaluate the figures on student fights, gang activity, and other safety indicators with respect to student backgrounds, school assignment, and the lack of high-quality learning options available to these students.

In a 2018 report, Heriot and co-author Alison Somin cited a study that challenges the claim that disproportionate discipline rates are due to racism. In the Journal of Criminal Justice, researchers wrote, “The inclusion of a measure of prior problem behavior reduced to statistical insignificance the odds differentials in suspensions between black and white youth.” Heriot and Somin further note that these researchers “found that once prior misbehavior is taken into account, the racial differences in severity of discipline melt away.”

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos discussed these findings at a congressional hearing in 2019, where Representative Katherine Clark (D–MA) criticized the research and accused Secretary DeVos of saying that “black children are just more of a discipline problem.”

However, the lead researcher of the study in question, J. P. Wright, told U.S. News & World Report that “I would never say that black children are, categorically, more of a discipline problem than other students,” but “any number of studies show that problem behavior, including juvenile delinquency, is not uniformly distributed across racial groups.”

The first randomized control trial study of “restorative justice” in a major urban district, Pittsburg Public Schools, was published by the RAND Corporation. The results were notable. While the teachers surveyed reported improved school safety, professional environment, and classroom management ability, those teachers knew their supervisors who were supporting the programs would be reading the survey results. Interestingly, the researchers then interviewed the students in those classrooms separately, and found that students disagreed, thinking their teachers’ classroom management deteriorated, and that students in class were less respectful and supportive of each other, and they reported bullying and more instructional time lost to disruption. “Restorative justice” also had no impact on student arrests. The most troubling finding was that there were significant and substantial negative effects on math achievement for middle school students, black students, and students in schools that are predominantly black. Summaries of the results of other studies of “restorative practices” programs can be found here and here.

As the Hechinger Report notes:

[M]ore sophisticated research has been commissioned, and the results are starting to trickle in. For proponents of restorative justice, the first two studies are not especially promising with both failing to show clear benefits for these non-punitive approaches to student discipline. Academic achievement fell for some students who were exposed to restorative justice compared to students at schools who were disciplined as usual. Implementation problems were common. Both studies were conducted by RAND Corporation, a research firm, which randomly assigned schools in the city of Pittsburgh and the state of Maine to try restorative justice practices. The Pittsburgh study was commissioned by National Institute for Justice as part of its Comprehensive School Safety Initiative. (The institute is a research, development and evaluation agency of the U.S. Department of Justice .) The Maine study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a unit of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services … The academic performance of middle schoolers actually worsened at schools that tried restorative justice. Math test scores deteriorated for black students in particular. The number of student arrests was similar at both treatment and control schools. That suggests the restorative justice experiment wasn’t doing much to alleviate the school-to-prison pipeline … [S]tudents reported that teachers struggled more to manage classroom behavior. I wondered if disruptive behavior in the classroom might have detracted from learning time, or perhaps even worthwhile and productive restorative justice conversations ate away at precious instructional minutes. Either way, it could potentially explain why some kids’ performance suffered.

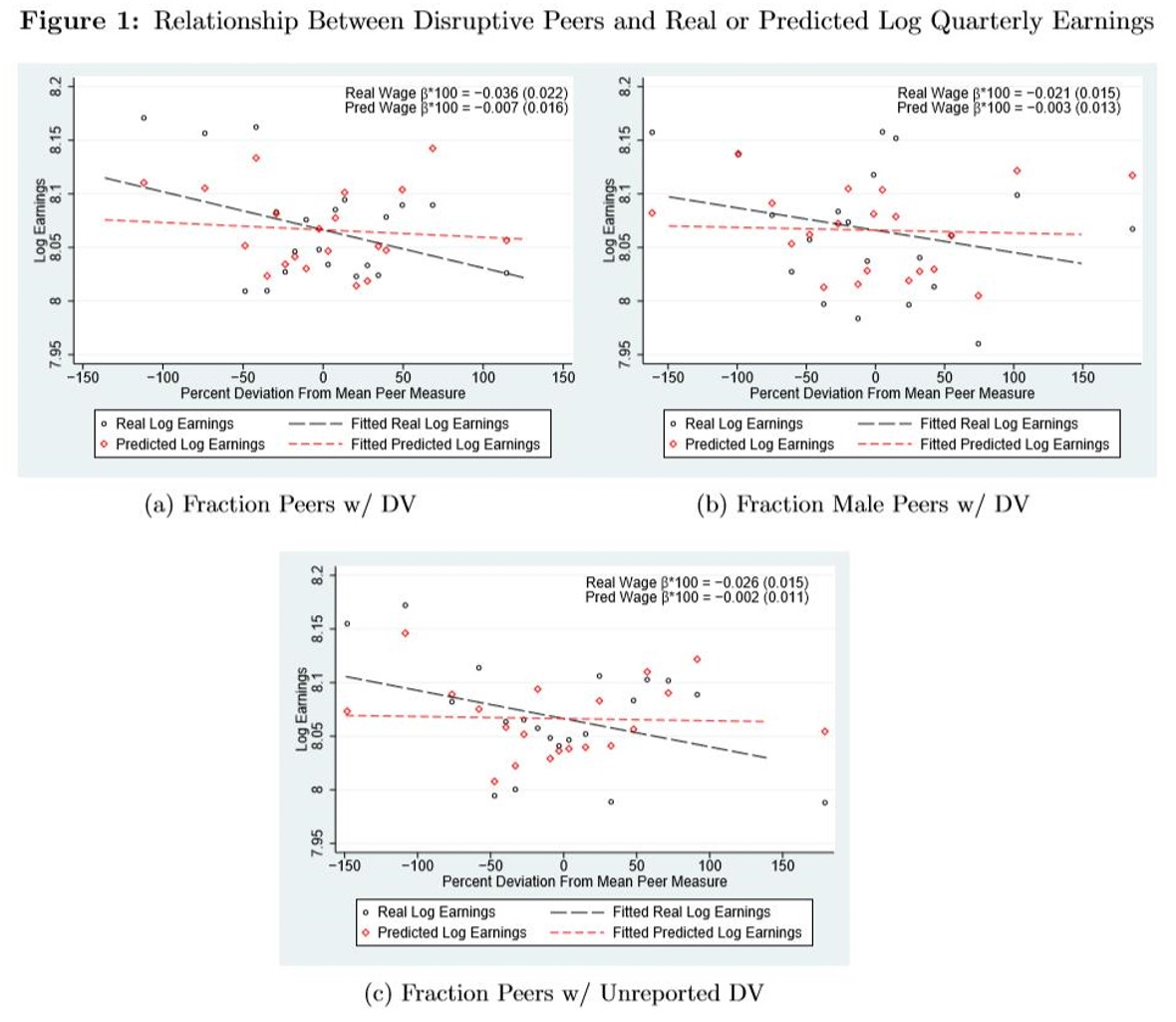

If disruptive students are allowed to remain in class, all other students have their learning disrupted, including minority students. Researchers have found that children who were exposed to an above-average (within-school) concentration of disruptive peers in elementary school have much lower-than-predicted future earnings. They predict that adding one disruptive peer to a class of 25 will result in earnings reductions of over 3 percent.

The experience in Alexandria, Virginia, is similar to that of other suburban district that have adopted “restorative practices.” As described in the Wall Street Journal:

Wauwatosa is one of thousands of districts to have adopted a “restorative justice” policy. This is an alternative to traditional discipline structures that emphasizes dialogue over punishment and focuses on revising school policy rather than changing student behavior. In February 2025, the Wauwatosa school superintendent retained a consultant to investigate the “professional culture” at McKinley Elementary School. The final report, dated May 9, reveals that disruptive students received treats “in the form of food and beverages” and a chance to play games in the office instead of a standard detention. To no one’s surprise, Wauwatosa schools have developed a reputation for permissive discipline and frequent fights. The chaos that results from leniency has led to more expulsion notices than is typical.

As Nat Malkus writes, recent U.S. poor performance on standardized tests cannot be attributed solely, or even primarily, to closure policies related to the COVID pandemic:

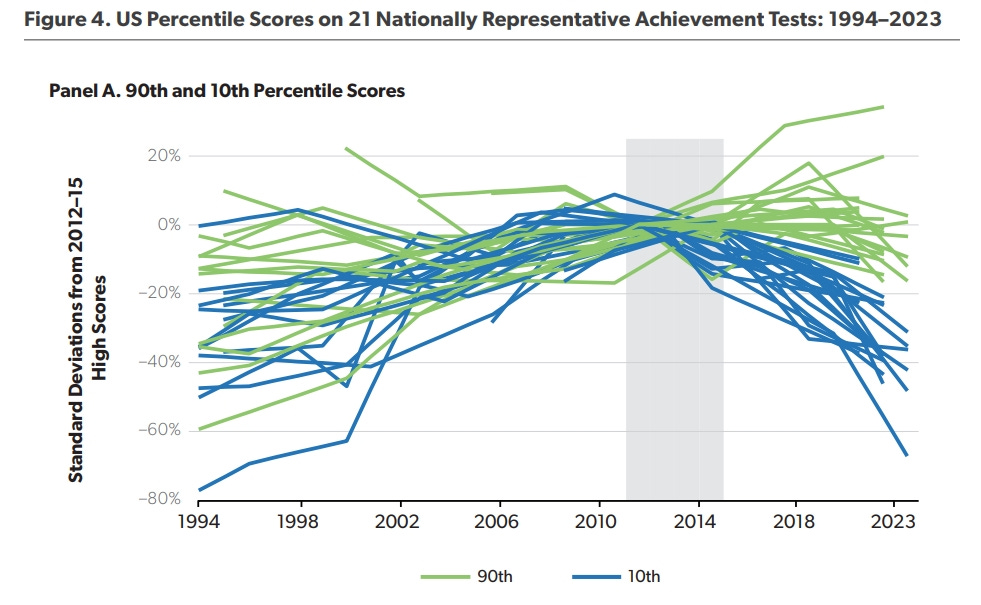

[There are some] implicit stories of student achievement that, I argue in this report, are not supported by a careful analysis of recent test score trends. The first implicit story is that declining student performance in recent years is solely attributable to the pandemic: If test scores have declined, that is the result of the pandemic’s aftereffects; if test scores have improved, that is because we have moved past the pandemic … Indeed, average test scores began declining well before the pandemic, suggesting that the decline in test scores over the pandemic was perhaps not solely attributable to the pandemic and that test scores could continue to decline in the coming years for reasons that have little to do with COVID-19. The second implicit story is that things are getting much worse for all students … In fact, on a number of tests and in a number of subjects, higher-achieving students have held steady over the past decade … [A]fter 2012–15, there is a stark separation in trends across percentile groups: The lower percentiles trend downward, while the relatively higher percentiles are closer to zero. These lines show a remarkably consistent pattern across subjects and grades, whereby scores are not falling equally across the achievement distribution. Since the early 2010s, assessment scores vary, but scores for higher performers are relatively stable while scores for the bottom of the distribution fall rapidly, meaning that absolute achievement gaps have widened considerably …

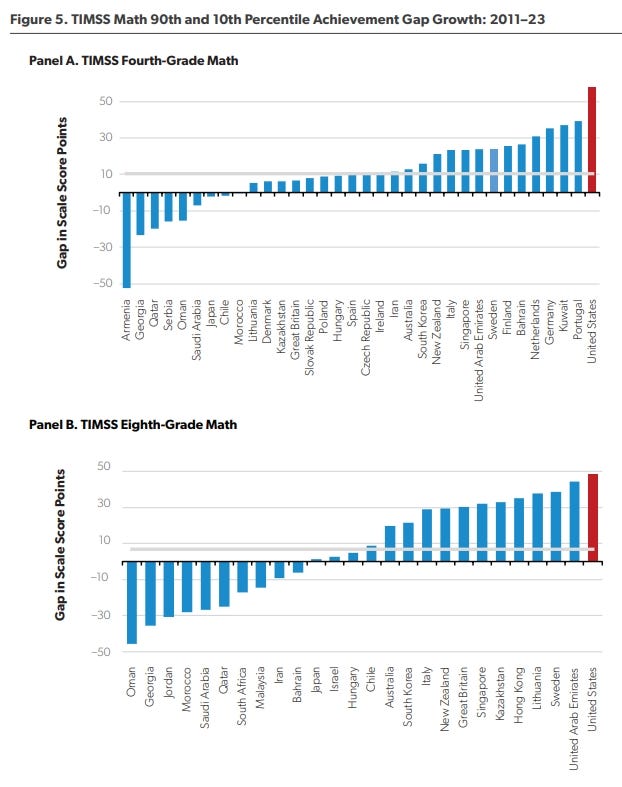

[I]nternational results also reveal that this pattern is a peculiarly American phenomenon. Indeed, results from other countries do not reflect, either in consistency or degree, the same dual trend of a decline starting in the early 2010s and an increasing absolute achievement gap between the highest and lowest performers …

[Note: TIMSS is the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, which assesses science and math for grades four and eight.]

[P]lausible explanations [for the downward trend in aggregate test scores] must accommodate four key attributes: a downward trend beginning around 2013; declines driven by the bottom half of the distribution, both pre- and post-pandemic; higher absolute achievement gap growth in the US than in any other nation; and the similarity of these declines for US students and adults.

One such plausible explanation is the growth in the use of the term “equity” in education, particularly in urban and suburban area, that occurred starting in the 2010’s.

Further, as Frederick Hess points out:

[V]ocal voices in the restorative-justice community tend to unapologetically blame misbehavior more on “problematic” societal structures than on bad choices, suggesting that they don’t ultimately accept the notion of personal agency—or that wrongdoers should be held personally responsible for their misbehavior.

I wrote previously on the importance of recognizing individual agency.

The role “restorative practices” played in allowing the Parkland school shooter (who killed 17 people) to avoid arrest (and thereby to avoid the prohibition on a gun purchase with an arrest record) was hardly mentioned in the extensive press coverage of that tragic event, but it is explored in detail in Andrew Pollack and Max Eden’s book Why Meadow Died: The People and Policies That Created the Parkland Shooter and Endanger America’s Students. Consequently, portions of that book are worth quoting at length, as it ties together many of the threads connected in this essay:

This book [about the Parkland school shooter] is about the Broward County school district. It might sound strange to point a finger at the schools. After all, when people think of schools, they think about caring teachers who want to do right by kids. But teachers don’t have much power anymore. They report to their principals, who report to district bureaucrats and superintendents. In theory, superintendents report to locally elected school boards that are accountable to citizens. But citizens don’t have much power over our schools anymore either. Instead, school superintendents follow orders and cues from federal bureaucrats and social justice activist groups. Those folks view students and schools as statistics on a spreadsheet. They slice every data set by students’ race, income, and disability status, and then blame every inequality on teachers …

One policy is known as “discipline reform” or “restorative justice.” … They essentially accused teachers of racism and sought to prevent teachers from enforcing consequences for bad behavior. They thought that if students didn’t get disciplined at school, if instead teachers did “healing circles” with them or something, then students wouldn’t get in trouble in the real world. Superintendents then started pressuring principals to lower the number of suspensions, expulsions, and school-based arrests. All that actually happened was that everyone looked the other way or swept disturbing behavior under the rug, making our schools more dangerous …

In 2013, Broward County Public Schools superintendent Robert Runcie launched the PROMISE program, which made him a national education superstar. The PROMISE program was the cornerstone of Broward’s new disciplinary leniency policies. Runcie sought to fight the so- called “schoolhouse-to-jailhouse pipeline” by lowering suspensions, expulsions, and arrests. He made it harder to suspend and expel and arrest students, and as those discipline statistics plummeted, Runcie’s star rose … [Teachers] saw bullying rise because teachers no longer had the authority to police it. Before, teachers could immediately send a student to the assistant principal’s office for misbehavior. But now, they had to fill out extensive paperwork first. And if they still sent a student to the office, teachers found that administrators were more likely to blame rather than support them …

[T]he official “collaborative agreement” between the Broward school district and sheriff’s office on how to handle crimes in schools [provided that] [s]tudents get three free misdemeanors a year before school administrators are even allowed to talk to law enforcement … Everyone was saying that the shooter had committed all sorts of crimes at school but was never arrested. The school district had a policy to do everything it could not to arrest students … Robert Martinez, a recently retired school resource officer, [said] “We all knew some sort of tragedy like this was going to happen in Broward. You can’t just stop arresting kids without expecting something like this. As officers, our hands were tied.” …

Take a moment to put yourself in the position of any of Cruz’s teachers. You have diligently documented this student’s deranged behavior for months. You have related [Nikolas] Cruz’s [the school shooter’s] many threatening statements to your assistant principal, as well as his troubling preoccupation with guns, killing, and cannibalism. All of your colleagues have had similar experiences with this student. You have expressed the opinion, supported by extensive “data,” that Cruz is a danger to others and belongs at a specialized school … [Yet] in K-12 education, rather than try to make amends after a punishment, RJ [restorative justice] is done instead of punishment. It includes practices such as “reparative” dialogues to address the “root causes” of misbehavior, “healing circles,” and peer counseling …

Threatening to shoot up a school is a felony that, if successfully prosecuted, could have prohibited Cruz from buying a firearm. (And even if Cruz was not convicted, an arrest could have gone a long way toward law enforcement taking future reports about Cruz seriously.) But [the police officer] declined even to write a police report about the call …

To recap: a deeply disturbed student with a history of threatening to shoot up the school and kill his peers … At that point, five students provided statements to Assistant Principal Porter that Cruz had threatened to kill people and brought weapons to school. They also expressed concerns that Cruz might be carrying weapons and could kill someone the next time he became angry … It is difficult to imagine a set of circumstances that would more strongly argue for an arrest. But Scot Peterson’s police logs from that month show no evidence that he was even consulted. Instead, administrators gave Cruz a two-day internal suspension and developed a “safety plan” that banned him from bringing a backpack on campus and frisked him every day. The obvious rationale: if he has a backpack, he could bring a deadly weapon to school and kill people. They decided that Nikolas Cruz was too dangerous to be allowed on campus with a backpack but he should not be arrested. This may seem astonishing, but it is actually entirely faithful to philosophy of the Broward school district, as expressed by Superintendent Runcie: “We are not going to continue to arrest our kids” and give them a criminal record …

Cruz commented on a YouTube video under the username “nikolas cruz” that he wanted to become a “professional school shooter.” The video’s creator, Mississippi bail bondsman Ben Bennight, alerted the FBI. The FBI interviewed Bennight, but he knew nothing beyond what he had already told them: a “nikolas cruz” said that he wanted to become a school shooter. An agent searched FBI databases but found nothing (because Cruz had no criminal record) and closed the case …

You have to understand why it happened, the policies and the culture that made the most avoidable mass murder in American history somehow inevitable … At first, a lot of the media attention focused on the PROMISE program, which explicitly decriminalized misdemeanors … PROMISE was cornerstone of a culture of leniency that encouraged school administrators and police to systematically look the other way when students misbehaved. All those red flags at MSD [the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas school] weren’t missed by accident. They were missed by design. By administrators who were, more or less, following orders …

Broward’s PROMISE agreement became nationally famous the day it was signed, November 5, 2013. That day, Education Week ran an article headlined, “Revolutionizing School Discipline, With a Flowchart.” The article explained, “Harsh discipline policies are falling out of favor across the country, but Broward County, Fla., is hoping to do away with them entirely.” Superintendent Runcie expressed alarm that 5 percent of Broward’s black students were suspended, which was twice the rate of Broward’s white students. He also expressed alarm that Broward had more than a thousand school- based arrests in a school year. Those statistics fell well under the national average, but Runcie declared, “If we don’t find ways to turn this around and give them an opportunity, we’re wasting a lot of lives.”

The same day, NPR’s All Things Considered also highlighted the PROMISE program. It explained that “one of the nation’s largest school districts has overhauled its discipline policies with a single purpose in mind—to reduce the number of children going into the juvenile justice system.” This was a move away from “zero tolerance” and an effort to end the so- called “school- to- prison pipeline.” Activists contended that the fact that students of color were disciplined more frequently than white students was evidence that teachers and principals were engaging in racial discrimination, and that by unfairly disciplining students, teachers were putting them on a path toward incarceration. NPR noted, “Civil rights and education activists say the policy can be a model for the nation.” …

Runcie told Scholastic that “some of my staff joke that the Obama administration might have taken our policies and framework and developed them into national guidelines.” But it was not a joke. The Broad Center, a left- leaning, billionaire-funded education reform group, put it plainly in 2018, one month before the Parkland massacre: “PROMISE informed the White House’s guidance on student disciplinary practices nationwide.” …

In his speech announcing the major federal policy shift, Runcie’s old boss, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, declared that, “Racial discrimination in school discipline is a real problem today,” and pointed to data collected by the Department of Education that showed black students are suspended at three times the rate of white students. This disparity in school discipline, he added, “is not caused by differences in children; it’s caused by differences in training, professional development, and discipline policies.” Therefore, he declared, “It is adult behavior that needs to change.” …

The “Dear Colleague Letter” (DCL) sent out by Arne Duncan at the Department of Education and Eric Holder at the Department of Justice embodied Broward’s approach to school discipline, but it was much more than “guidance.” The DCL was the pretext for a largely secret and coercive campaign of bad-faith investigations intended to compel school districts across the country to adopt Broward’s policies. The DCL, issued two months after PROMISE was launched, fundamentally changed the standard for federal investigations into civil rights violations regarding school discipline. Before, the role of civil rights enforcement was clear: Students may not be treated differently because of their race. If a black student and a white student both curse at a teacher, it would be a civil rights violation to discipline them unequally. But the DCL changed the standard from equal treatment to equal outcomes. Statistical differences in disciplinary rates were now taken to be prima facie evidence of a civil rights violation. After the DCL, if two black students and one white student all cursed at a teacher, it could be a civil rights violation to discipline them equally (depending on the racial composition of the school district) …

Teachers say these policies make them less safe. In Oklahoma City, 60 percent of teachers said that offending behavior had increased since the district adopted new so-called “positive” and “restorative” discipline policies. In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 60 percent of teachers said that they had experienced an increase in violence or threats and 41 percent said they did not feel safe at work. In Portland, Oregon, 34 percent of teachers said their school was unsafe. In Jackson, Mississippi, 65 percent said their school “feels out of control” on a daily or weekly basis. In Denver, Colorado, 32 percent of teachers said discipline issues had compromised their personal safety and 60 percent said discipline issues had harmed their mental health. In Syracuse, New York, 36 percent of teachers had been physically assaulted by students, 57 percent had been threatened, and 66 percent had feared for their safety at school.

Finally, the book also mentions a common dynamic in school board elections that is often overlooked: “[I]n school board elections, with low turnout and teachers often the only voters paying attention, the teachers union president is often the kingmaker … Traditionally, the only people who stand outside the polls for school board races are folks who are paid by teachers unions.”

And indeed, one of the few local school board members here in Alexandria, Virginia, who supported creating a “restorative practices coordinator” over the school staff’s own objections (as mentioned at the beginning of this essay) is a current teachers’ union employee whose boss, Randi Weingarten, personally canvassed for her.

Excellent. This reminds me that the far left (well, any ideologue) would be lost without the "post hoc, ergo propter hoc" fallacy.