School Boards – Part 2

Randi Weingarten and the American Federation of Teachers union.

In this essay, we’ll look at one particular national teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, and, in a subsequent essay, examine how its reach extends all the way down to local school board elections where I live.

I first became aware of Randi Weingarten (now the head of the American Federation of Teachers union) when she was the head of the United Federation of Teachers in New York City, and I read a story about the “rubber room” for New York City public school teachers. Back then, Weingarten was the head of the union that negotiated the rules that led to the “rubber room.”

What was the “rubber room”? Terry Moe sets the scene in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

Janet Archer painted watercolors. Gordon Russell planned trips to Alaska and Cape Cod. Others did crossword puzzles, read books, played chess, practiced ballet moves, argued with one another, and otherwise tried to fill up the time. The place was New York City. The year was 2009. And these were public school teachers passing a typical day in one of the city's Rubber Rooms — Temporary Reassignment Centers — where teachers were housed when they were considered so unsuited to teaching that they needed to be kept out of the classroom, away from the city's children.1 There were more than 700 teachers in New York City's Rubber Rooms that year. Each school day they went to “work.” They arrived in the morning at exactly the same hour as other city teachers, and they left at exactly the same hour in the afternoon. They got paid a full salary. They received full benefits, as well as all the usual vacation days, and they had their summers off. Just like real teachers. Except they didn't teach. All of this cost the city between $35 million and $65 million a year for salary and benefits alone, depending on who was doing the estimating.2 And the total costs were even greater, for the district hired substitutes to teach their classes, rented space for the Rubber Rooms, and forked out half a million dollars annually for security guards to keep the teachers safe (mainly from one another, as tensions ran high in these places). At a time when New York City was desperate for money to fund its schools, it was spending a fortune every year for 700-plus teachers to stare at the walls. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Chancellor Joel Klein wanted to move bad teachers out of the system and off the payroll. But they couldn't. While most of their teachers were doing a good job in the classroom, the problem was that all teachers — even the incompetent and the dangerous — were protected by state tenure laws, by restrictive collective bargaining contracts, and by the local teachers union, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), which was the power behind the laws and the contracts and the legal defender of each and every teacher whose job was in trouble … As UFT president Randi Weingarten artfully explained, “All we're looking for is due process.” A New York City principal, acutely aware of the bad teachers that “due process” so completely protects, saw the same situation differently. “Randi Weingarten,” he said, “would protect a dead body in the classroom. That's her job.” And she did it well. Every teacher in New York City had more due process than O. J. Simpson. Because of it — and because of the union power that lay behind it — the city's children were being denied tens of millions of dollars every year: money that should have been spent on them, but wasn’t … These formal rules are part of the organization of New York City's schools. In fact, they are central to it. The district is literally organized to protect bad teachers and to undermine the efforts of leaders to ensure teacher quality. It is also organized to require that huge amounts of money be wasted on endless, unnecessary procedures. These undesirable outcomes do not happen by accident. They are structured into the system. They happen by design.

Beyond engineering the rubber room, Weingarten has since become famous for orchestrating the extended closure of public schools during the COVID pandemic by conditioning the reopening of schools on things far beyond what any of the science would have seemed to indicate as prudent at the time. And in between, she’s been the most public face of arguments presenting the “teachers union side” of just about any issue.

Her most commonly-used argument is addressed by Moe:

Randi Weingarten, for example, trades on the fact — and it is a fact — that the southern and border states tend to have less collective bargaining and lower academic achievement than other states do. It is a fact, then, that the states with collective bargaining tend to do better academically than the states without it. But she goes on to assert — quite publicly and quite often — that therefore collective bargaining is not having negative effects on achievement. As she puts it, “The states that actually have lots of teachers in teacher unions tend to be the states that have done the best in terms of academic success. And the states that don't tend to be the worst. The issue is not a teacher union contract.” She executes the same sort of logical maneuver in making comparisons across nations, noting that, because Finland, Singapore, and other high-scoring nations have collective bargaining, this “debunks the myth” that collective bargaining has negative consequences for achievement. There is no logical basis for this kind of causal inference. Finland has collective bargaining and also has high levels of student achievement, but that says nothing about the causal impact of collective bargaining on achievement. Countless other factors that affect achievement — Finland's small size, homogeneity, culture, investment in education, recruitment of teachers, family structure, virtual absence of poverty, and so on — are simply being ignored. It is entirely possible that, if Finland had no collective bargaining at all, its schools would do even better. Moreover, the very nature of collective bargaining is starkly different in Finland, where labor relations are founded on broad national agreements among national organizations and look nothing like the U.S. system of district-level bargaining and detailed local contracts; indeed, the hallmark of Finnish schools is their autonomy from detailed formal rules specifying what they must do and how. To talk about the impact of “collective bargaining” on student achievement in Finland and the United States, then, is to be talking about two very different things. A similar logic applies to Weingarten’s spurious comparisons across the American states. While it is true that the southern and border states have less collective bargaining (of the U.S. type) than the remaining states, they are also quite different from these states in all sorts of other ways too …

As Michael Hartney writes in his book How Policies Make Interest Groups: Governments, Unions, and American Education:

In a 2010 appearance on ABC’s This Week, AFT president Randi Weingarten sought to discredit any potential linkage between unions and lower student achievement by arguing that “the states that actually have lots of teachers in teacher unions tend to be the states that have done the best in terms of academic success ... And the states that don’t tend to be the worst.” … [T]he summary of the evidence that is relied upon to make these claims is outdated, both temporally and methodologically … [I]n recent years a handful of scholars have begun to examine teacher-union strength in the content of CBAs [collective bargaining agreements], highlighting ways in which some CBAs are restrictive toward school management. The vast majority of these CBA-restrictiveness studies have found that restricting the autonomy of school leaders is associated with negative impacts on student achievement, especially for disadvantaged students.

Regarding the results of teachers union collective bargaining on kids’ future job prospects generally, the first analysis of the effect of teacher collective bargaining on long-run labor market and educational attainment outcomes by researchers at Cornell suggests that teachers union collective bargaining worsens the future labor market outcomes of students. As the researchers write:

Our estimates suggest that teacher collective bargaining worsens the future labor market outcomes of students: living in a state that has a duty-to-bargain law for all 12 grade-school years reduces earnings by $800 (or 2%) per year and decreases hours worked by 0.50 hours per week. The earnings estimate indicates that teacher collective bargaining reduces earnings by $199.6 billion in the US annually. We also find evidence of lower employment rates, which is driven by lower labor force participation, as well as reductions in the skill levels of the occupations into which workers sort. The effects are driven by men and nonwhites, who experience larger relative declines in long-run outcomes.

The researchers’ bottom line is that “We find strong evidence that teacher collective bargaining has a negative effect on students’ earnings as adults.” The study compared outcomes for students in states that mandate collective bargaining before and after the collective-bargaining requirement was imposed to outcomes for students over the same period in states that did not require collective bargaining. It also adjusted for the share of the student’s state birth cohort that is black, Hispanic, white and male. Students who spent all 12 years of their elementary and secondary education in schools with mandatory collective bargain earned $795 less per year as adults than their peers who weren’t in such schools. They also worked on average a half hour less per week, were 0.9% less likely to be employed, and were in occupations requiring lower skills. The authors found that these factors added up to an overall loss of $196 billion per year for students educated in the 34 states with mandated collective bargaining.

As Philip Howard writes in his book Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions:

The harm done to generations of American students is not an accident but is the deliberate exercise of union political power, now enshrined in layers of law. “The more restrictive the contract,” studies show, “the lower the gains in student achievement” [according to Dale Russakoff in his 2015 book The Prize]. There are many good schools, but their common thread is that they have cultures in which educators basically ignore the rules. It would be a challenge to find any good school where teachers focus on their entitlements … [T]he union party cannot boast of great public works or other clear accomplishments for the public good. It works only for its own benefit. Studies find that unions have the effect of increasing public spending, but not with corresponding public benefits. For example, Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby in 1996 found that teachers unions “succeed in raising school budgets and school inputs but have an over-all negative effect on student performance.”

As Mark Zupan writes in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest (referencing the same Hoxby study):

Hoxby also shows that unionization results in greater per-pupil spending and poorer student outcomes, the latter being measured by high school dropout rates. Over the period 1972–1982, per-pupil spending grew by 12.3 percent more in unionized school districts than in nonunionized districts, holding all other factors constant. Three-quarters of the added spending in unionized districts was devoted to either higher teacher salaries or hiring more teachers. Unlike for nonunionized schools, however, the added spending in unionized districts was unproductive. High school dropout rates for unionized schools were 2.3 percentage points worse than for nonunionized schools, holding constant demographic factors such as median household income, population in poverty, racial/ethnic composition, total K-12 enrollment, private K-12 enrollment, average adult education level, median monthly rent, and percentage of the population aged 16–19. The negative effect of per-pupil spending on student outcomes in unionized districts stands in marked contrast to the positive effect of additional spending on student outcomes in nonunionized districts. A similar positive influence of additional spending on student performance has been documented by studies examining student cohorts educated prior to 1960 and the onset of unionization of K-12 public teachers in the United States.35 Whereas additional spending in nonunionized districts appears to be applied toward enhancing student outcomes, such spending in unionized districts is consumed by government insiders. Political scientist Terry Moe corroborates Hoxby’s findings by examining a large sample of California school districts. He finds that, after controlling for demographic factors and school/district characteristics, the restrictiveness of the district’s collective bargaining contract has a large negative impact on student achievement; it also exceeds the effect of any other organizational aspect of schools and districts. The negative effect is most pronounced for schools with a high percentage of minority students. This suggests that unionization by public school teachers extracts an especially heavy toll on how much minority children learn and hence the opportunities available to them later in life.

These union rules embodied in collective bargaining agreements impose high costs on students. As Zupan writes:

Teachers unions’ political clout has ossified anti-student policies, such as teacher tenure, seniority preferences, and lock-step pay. The more that teacher employment and compensation are based on tenure, seniority, and degree status, the less strongly they are linked to student outcomes. Moreover, studies find little evidence that the contractual provisions regularly supported by unions – requiring state teaching licenses, tenure, basing pay on years of service and graduate degrees earned, and so on – increase teacher effectiveness in the classroom … As of 2012, the Slovak Republic spent only 54 percent as much per K-12 pupil as the United States but achieved comparable student outcomes. Shanghai-China, Singapore, Hong Kong-China, and Macao-China – all non-OECD members but PISA participants – appreciably outperform the United States in reading, science, and mathematics educational outcomes while spending much less per pupil … Using school district and tax records for more than 1 million children, economists Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff find that students assigned to high value-added teachers – as measured by the teachers’ impacts on students’ test scores – are more likely to go to college, attend a higher-quality college, earn higher salaries, and invest in a 401(k) retirement savings plan; they are also less likely to have children as teenagers. Replacing a poorly performing K-12 teacher, whose value added ranks in the bottom 5 percent, with an average one is estimated to increase the present value of students’ lifetime earnings by $250,000 per average-size classroom. These results suggest that substantial socioeconomic gains can be realized in the United States by a K-12 system empowered to dismiss poorly performing teachers and to reward highly performing ones. On a larger scale, it has been estimated that replacing the bottom 5–10 percent of public K-12 teachers with average teachers would be sufficient to move the United States from below average to near the top of the cross-country PISA measures of student outcomes. The performance-based accountability system such a change suggests would also increase cumulative future GDP by $102 trillion over the lifetime of the generation born in 2010. By comparison, the US GDP was estimated to be nearly $18 trillion as of 2015. According to another study, relying on high-impact instead of just average teachers for four to five consecutive years would suffice to eliminate entirely the educational gap that presently exists between low-income students on free or reduced-price lunch programs and average students not on such programs.

Hartley conducted his own research on the subject:

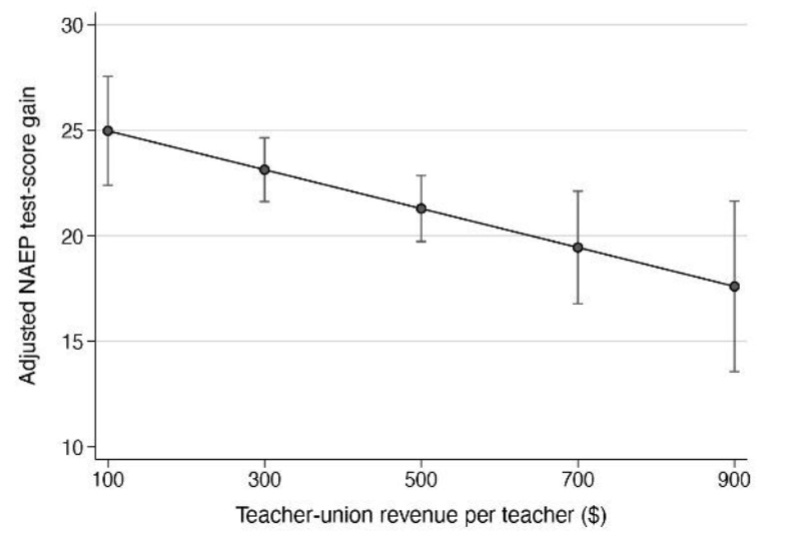

I analyze the relationship between union strength and changes in states’ performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) … Irrespective of the particular measure of teacher-union strength that is used, I find evidence that states with stronger unions made lower adjusted NAEP gains. Specifically, across five of the eight models, states with stronger teachers unions—those where NEA affiliates generated more union revenue per teacher and those ranked stronger on the Fordham union-strength index—made smaller adjusted NAEP gains between the 1990s and late 2010s … [M]oving from a state in the bottom ten of Fordham’s union-power ranking to one in the top ten was associated with five fewer points gained on the fourth-grade mathematics exam. Substantively, four points represents an effect size of more than half a standard deviation. This relationship between union strength measured as union dues revenue per teacher and adjusted NAEP gains on fourth-grade mathematics between 1996 and 2019 is shown visually in figure 8.3.

Hartley continues:

In both math and reading, student cohorts educated in states that had rolled back union power made higher relative gains than students in states that left union power untouched. The impact of union retrenchment ranges from 2.4 to 3.6 more points gained on the NAEP between fourth and eighth grade. These differences represent an effect size of about three-quarters of a standard deviation … Taken together, these results seem to indicate two things. First, states that enacted labor-retrenchment laws increased the pace of learning gains between fourth and eighth grade in the years after those laws went into effect. Second, irrespective of gains, comparable student populations performed no worse and, in the case of reading, better by the time they reached eighth grade after their state had weakened its teacher labor law. At the very least, these results indicate that the string of labor-retrenchment laws that were adopted in 2011 had no significant negative impact on student performance in the aggregate. Eight full years after retrenchment laws went into effect, eighth-grade students — whose schooling had occurred entirely under weaker labor laws — fared no worse and, on the whole, mostly better than their peers in the previous decade, when their state had stronger teacher labor laws. This finding is important because, if policymakers were able to realize costs savings of any kind in the aftermath of labor-law reforms, those cost savings came without any significant negative returns to student achievement.

As the Wall Street Journal writes:

[T]he teachers unions use their failure to deliver better results as an excuse for ever-more money. Union boss Randi Weingarten on Wednesday claimed the “stagnant” NAEP scores show the need for “expanding community schools to provide wraparound services”—e.g., social and healthcare services—and “securing investments for smaller class sizes, good ventilation and the tools and technology for 21st-century learning.” Sorry, children aren’t doing worse because of bad air filters or old computers. They scored better without 21st-century technology.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at the direct influence the national American Federation of Teachers union has on local school board elections in my own city of Alexandria, Virginia.

Paul,

Wow, these are awful people doing awful things. This is just such valuable content. Thanks.