Instead of Closing the Knowledge Gap with Learning, Many Educational Bureaucrats Are Lowering Standards

I wrote previously about the “Knowledge Gap,” and how research has shown that kids can only become proficient readers when they come to have sufficient background knowledge about the world, knowledge that allows them to fill in the gaps writers assume most readers know already. Without that gap-filling ability, kids can’t comprehend much of what they read.

As Robert Pondiscio writes, this finding was recently confirmed by researchers at the University of Virginia:

A remarkable long-term study by University of Virginia researchers led by David Grissmer demonstrates unusually robust and beneficial effects on reading achievement among students in schools that teach E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge sequence. The working paper offers compelling evidence to support what many of us have long believed: Hirsch has been right all along about what it takes to build reading comprehension. And we might be further along in raising reading achievement, closing achievement gaps, and broadly improving education outcomes if we’d been listening to him for the last few decades. I’ve described countless times how teaching fifth grade in a low-scoring New York City public school made me a Hirsch disciple and a Core Knowledge enthusiast. Hirsch’s work—and only Hirsch’s work—described uncannily what I saw every day in my South Bronx classroom: children who could decode written text but struggled with reading comprehension. My school’s staff developers, district consultants and coaches, ed school professors, and the literacy gurus they assigned us to read and study had different explanations for students’ reading struggles: Children were bored by required texts that didn’t reflect their interests and personal experiences. If we let them read what they wished, it would be more pleasurable and they’d spend more time at it. Classroom instruction was built around an all-purpose suite of reading “skills and strategies” that students could apply to any book. We were to “teach the child not the lesson,” make them fall in love with books and develop a “lifelong love of reading.” When students who appeared to be successful under this “child-centered” vision of literacy struggled on standardized tests, there was an answer for that, too: test anxiety and “inauthentic” assessments. For more than four decades, Hirsch has responded to all this with a simple, cognitively unimpeachable, hiding-in-plain sight rejoinder: No, it’s background knowledge. Sophisticated language is a kind of shorthand resting on a body of common knowledge, cultural references, allusions, idioms, and context broadly shared among the literate. Writers and speakers make assumptions about what readers and listeners know. When those assumptions are correct, when everyone is operating with the same store of background knowledge, language comprehension seems fluid and effortless. When they are incorrect, confusion quickly creeps in until all meaning is lost. If we want every child to be literate and to participate fully in American life, we must ensure all have access to the broad body of knowledge that the literate take for granted. The effects of knowledge on reading comprehension are well understood and easily demonstrated. The oft-cited “baseball study” performed by Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie showed that “poor” readers (based on standardized tests) handily outperform “good” readers when the ostensibly weak readers have prior knowledge about a topic (baseball) that the high-fliers lack. We also know that general knowledge correlates with general reading comprehension. University of Virginia cognitive scientist Dan Willingham, a co-author of the study, put it best in a video he made years ago: Teaching content is teaching reading. What has been more difficult to prove is that a specific curricular intervention aimed at systematically building students’ background knowledge can raise reading achievement. What the new study suggests is that not only is Hirsch’s theory solid, so is his prescription. The six-year randomized control trial followed over 2,300 students who applied for kindergarten to one of nine oversubscribed Core Knowledge charter schools in the Denver area. Nearly 700 students who won seats in the lottery were compared to students who applied but ended up matriculating elsewhere. Researchers looked at state test results from third through sixth grade. The cumulative long-term gain from kindergarten to sixth grade for the Core Knowledge students was approximately 16 percentile points. Grissmer and his co-authors put this into sharp relief by noting that if we could collectively raise the reading scores of America’s fourth graders by the same amount as the Core Knowledge students in the study, the U.S. would rank among the top five countries on earth in reading achievement. At the one low-income school in the study, the gains were large enough to eliminate altogether the achievement gap associated with income.

The results of this study come at a time when more and more teachers (unfortunately) emphasize activism over background knowledge. As Frederick Hess reports:

In a 2022 survey of K-12 teachers, for instance, the RAND Corporation found that more teachers thought civics education is about promoting environmental activism, rather than about “knowledge of social, political, and civic institutions.” In 2020, a RAND survey of high school civics teachers reported that just 43 percent thought it was essential for graduates to know about periods such as “the Civil War and the Cold War.” Less than two-thirds thought it essential for graduates to know the protections guaranteed by the Bill of Rights.

Ideological activists are also seeking not only to divide people by race, but to lower standards. As Max Eden writes:

California’s recently adopted, highly controversial math framework [which recommends lowering math standards] is a useful case study in how ideological assertions are laundered into the classroom as “evidence-based” best practices. In response, Stanford math professor Brian Conrad has drafted a 25-page document demonstrating how the claims made in the framework are either not supported or directly contradicted by research. Such slipshod pedagogical claims are common, however, in the work of the framework’s architect, Stanford education professor Jo Boaler, according to a Chronicle of Higher Education article. They’re also par for the course in education research and practice generally. Consider, for example, the evidence that the framework cites in support of “Trauma-Informed Pedagogy.” The framework cites a study titled “Healing-informed Social Justice Mathematics: Promoting Students’ Sociopolitical Consciousness and Well-being in Math Class.” … Authored by Kari Kokka, a mathematics education professor at the University of Nevada–Las Vegas, the study begins by explaining that students can experience the trauma of crime, violence, or abuse. She notes that studies demonstrate the effectiveness of school-based cognitive behavioral therapy, but none of these “centered cultural relevance.” … Kokka observed nine students being taught “Social Justice Mathematics.” After providing a “positionality statement” explaining that she was a “womxn of color,” Kokka describes the politicized math lessons. In one, [the] problem read: “I have US$100. I owe 1/4 of my money to my mom, 2/5 to my grandmother, and 4/10 to my brother. Do I have enough money to pay everyone back? How much money should each person get?” After students calculate that this woman owes more money than she has, they watch a video of a single mom struggling to make ends meet. They are then asked questions like, “What are some feelings that you are having when watching this video?” and “She works 40 hours a week and still struggles for food. What is your reaction around that?” Interviewed after the lesson, [a student] wrote, “I think that was sad, but I also got mad because the government or someone else of her family should help her.” … Several others expressed a commitment to political activism. “Students’ awareness of structural issues influenced their plans for taking action,” Kokka observed. “Taking critical action is part of radical healing and [Social Justice Mathematics] to gain a sense of agency and empowerment, a way of healing from trauma.” How well did the students learn math? That question wasn’t examined, but we shouldn’t be concerned: “[a]lthough traditional achievement data (e.g., standardized test scores) were not gathered, all nine focus students passed the course and interview data indicate that all focus students enjoyed engaging with [Social Justice Mathematics] tasks.” And that’s it – that’s the study. No evidence is offered suggesting that “trauma informed pedagogy” helps students learn math.

And as James Freeman writes in the Wall Street Journal:

Just what California students needed after lockdown learning losses: a new government policy to water down educational standards. Despite objections from math professors up and down the Golden State, Sacramento educrats announce in a Wednesday press release: “The California State Board of Education today approved the 2023 Mathematics Framework for California Public Schools, instructional guidance for educators that affirms California’s commitment to ensuring equity and excellence in math learning for all students.” Don’t believe it, because the standards will encourage schools to minimize algebra. Howard Blume and Teresa Watanabe report for the Los Angeles Times: “One area of criticism that gained steam last week was opposition from faculty members at the University of California and California State University systems. They were concerned about students using a data science class in place of Algebra II when fulfilling college admission requirements …” A majority of Black faculty members in UC science, math, technology and engineering fields said allowing data science to substitute for Algebra II would harm students of color by steering them away from math and science fields and undermine university efforts to improve diversity and equity. In May of last year this column noted the draft standards that progressives wanted to inflict on California’s K-12 math students. Stanford math professor Brian Conrad found “many misrepresentations” in the shoddy research used to justify the new standards. This week the Los Angeles Times reporters note: “Each draft fixed some problems but left many others unchanged,” said Brian Conrad, a math professor and director of undergraduate studies at Stanford. “A major overhaul is necessary.” Conrad was among those who asserted that the framework pervasively misstated and misapplied research in supporting its concepts. Many changes have been made based on such complaints, but Conrad said the use of citations remains unacceptably sloppy or ideologically tainted. One example, he said, was the use of a flawed and unpublished study — one that did not undergo the standard peer review — to oppose teaching Algebra I in eighth grade. In a Monday blog post before this week’s vote, Williamson Evers of the Independent Institute cited a foundational problem with the new standards: “Just as there is a science of reading instruction, there is a science of math instruction. The scientific way of teaching math includes: having students memorize math facts (like multiplication tables and addition and subtraction facts) and standard algorithms (time-tested math procedures); teaching computational procedures and conceptual understanding together (and not as progressives would have it, concepts before procedures); stressing that getting answers to problems right and doing so quickly are components of math fluency; and bearing in mind that committing math facts and procedures to long-term memory frees the student’s mind to handle novel problems. Instead, the progressive-education authors of the math framework want students to learn through their own inquiry and self-discovery. The authors give little emphasis to mastery of facts and standard algorithms. The authors want to organize math instruction not in the architectonic system of increasing abstraction in which it has traditionally been taught, but instead in accordance with vague, billowy ‘big ideas.’” How many billowy big ideas from Sacramento can the people of California stand? Lance Christensen of the California Policy Center tweeted the play-by-play commentary of the week on Wednesday: “Listening to the State Board of Ed hearing & it’s painful, technical drivel plowing forward to a pre-ordained conclusion. This is how the bureaucracy gets you. There is a lot of balderdash, bromides, platitudes, esoteric commentary, self-congratulations, excuses & acronyms in this hearing … What can we do going forward? Let’s find better curricula for the hundreds of school boards that are likely to (rightly) reject the state’s recommendation.”

Former Brookings Institution fellow Tom Loveless documented additional errors in the basis for the “new math,” and argued that the framework would put California students years behind the developed world. And as Faith Bottum writes in the Wall Street Journal:

To achieve equal outcomes, the framework favors the elimination of “tracking,” by which it means the practice of identifying students with the potential to do well. This supposedly damages the mental health of low-achieving students. The problem is that some students simply are better at math than others. To close the gap, the authors of the new framework have decided essentially to eliminate calculus—and to hold talented students back. The framework recommends that Algebra I not be taught in middle school, which would force the course to be taught in high school. But if the students all take algebra as freshmen, there won’t be time to fit calculus into a four-year high-school program. And that’s the point: The gap between the best and worst math students will become less visible ... A growing opposition from college professors should embarrass the Board of Education. More than 400 professors were incensed by a proposed data-science course as a math track that students might follow instead of Algebra II. “For students to be prepared for STEM and other quantitative majors in 4-year colleges . . . learning Algebra II in high school is essential,” they wrote in an open letter. “This cannot be replaced with a high-school statistics or data-science course, due to the cumulative nature of mathematics.”

All this, when admissions standards like those of the California Institute of Technology require either taking calculus in high school — or taking the extra time outside of school to learn it through private online educational courses like those offered by Khan Academy.

As I wrote in previous essays, high-level mathematics is essential to civilizational progress, and denying access to calculus to advanced students in high school can only lead to substantial costs to society. As I wrote in a previous essay, for example, calculus was the means of determining exactly which combination of drugs was necessary to stopping the ravaging effects of HIV-AIDS. Critical math skills are associated not just with better numerical understanding, but also with better understandings of the larger context necessary to better evaluate public policy and life choices generally, leading to better citizenship overall. According to Professor Kim Beswick, Director of the Gonski Institute and Head of the School of Education at the University of New South Wales:

Critical mathematical thinking encourages children to think about the way information is presented or framed. "Of course, real life is messier than math problems, but critical mathematical thinking encourages kids to consider the assumptions made and their limitations—that's the critical thinking part," she says. "It encourages them to ask the right questions. Do I have all the information I need to understand this? What don't I know? What should I ask? How can I find out that other information? What other factors should I consider? It's those sorts of questions. Who's got a vested interest in this story I just read in the newspaper?" And while it promotes a workforce supported by STEM capabilities, it's more than that, she says. "[Developing your critical math thinking] gives you more agency in the world. You can make better arguments. You can understand your medical treatment, or what your bank manager is telling you, what a proposed government policy might mean for you and for others," she says.

As Noah Smith writes: “When you ban or discourage the teaching of a subject like algebra in junior high schools, what you are doing is withdrawing state resources from public education. There is a thing you could be teaching kids how to do, but instead you are refusing to teach it. In what way is refusing to use state resources to teach children an important skill ‘progressive’?”

Sadly, as I’ve written previously, the lowering of math standards and the eliminating of “tracking” students with higher math aptitude into more advanced math classes appears to be something that’s been in the works for some time in my own local school system, even starting in grades four and five. Apparently, going forward, our local school board is abolishing the current system that allows students who have the demonstrated capacity to handle more challenging math problems to experience those challenges in their own classes specially designed to get them a year ahead in math. This seems to have happened on June 1, 2023, at a school board meeting at which there was no debate or public vote on the issue (see item 15 of the school board agenda of that day, available here, but note there is no corresponding link to any public debate or vote on that issue). I understand that, starting with fourth graders this year, students who are capable of more challenging math will no longer be able to progress ahead a full year, and progress accordingly from there going forward in their school career. (I confirmed that with a program teacher, who told me that, under the new program, the criteria for getting into the program was expanded to include subjective factors, and the curriculum was slowed down such that, for example, kids in the program no longer left it being a full year ahead in math.)

It seems to me the new program will end up resulting in a profound denial of education, and not just for students who would otherwise be able to handle more challenging math problems: as I’ve experienced while substitute teaching, when kids aren't challenged, they tend to become bored. And when kids tend to become bored, they tend to become disruptive. And when kids tend to become disruptive, they tend to distract other students from learning. It's a vicious cycle in which learning is increasingly denied. And it's a vicious cycle too many school boards are churning by implementing increasingly lower standards for academics and behavior.

Newton South High School in Massachusetts similarly watered down their advanced academic program, and math and physics teacher Ryan Normandin, who chairs the faculty council there, writes about its negative results in the Boston Globe:

In autumn 2021, against the already-challenging backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and remote learning, the Newton Public Schools decided to carry out a complex initiative at its two high schools known as “multilevel classrooms.” Previously, most classes at Newton’s high schools were given a label: honors, advanced college prep, or college prep, with honors offering the most challenging content. This system of “tracked classes” had its problems. Students who began their freshman year in a particular level could find it challenging to change levels, possibly making it harder for them to eventually take more advanced courses such as AP Calculus. To make matters worse, Black, Latino, and low-income students were disproportionately represented in lower-level classes. The multilevel model sought to rectify this problem by mixing the levels together into a single classroom taught by a single teacher. The district’s administrators claimed this would allow easier transitions among levels for students, increase exposure to more advanced content for lower-level students, and provide beneficial interactions among students who might otherwise never meet. [As to the results.] [s]tudents — at all levels of performance, but especially our students who need the most support and for whom this model was intended to help most — aren’t having their needs met. In one of my multilevel classes, I received feedback that the lower-level students didn’t want to ask questions because they didn’t want to “look dumb,” and the higher-level students didn’t want to ask questions because they didn’t want their classmates to “feel dumb.” The result was a classroom that was far less dynamic than what I was typically able to cultivate. Teachers — especially new hires — say they feel unheard and unsupported. During one meeting, an educator recounted their experience of finding a colleague crying in a closet because they felt like such a failure teaching multilevel… One world language teacher compared the challenge of meeting the varied needs of students to teaching a class where half the students are learning colors for the first time and the other half are analyzing a Salvador Dali painting. There’s nothing wrong with learning either — but in one room, it’s impossible to teach both simultaneously. Without adequate training or support, many teachers are forced to teach to the middle (let’s list all the colors in the Dali painting), leaving the highest-needs students lost and struggling and the highest-performing students bored and disengaged … The Faculty Council met with department heads all the way up to the superintendent, and what we found was shocking — Newton implemented this monumental change to instruction with no metric for success and no plans to collect data. In not a single conversation over three years could anyone present to us data showing that these classes had a positive impact on students.

He also writes that the school’s faculty collected data on their own showing the extent of the failure, but administrators just said they would study the issue and report findings next spring.

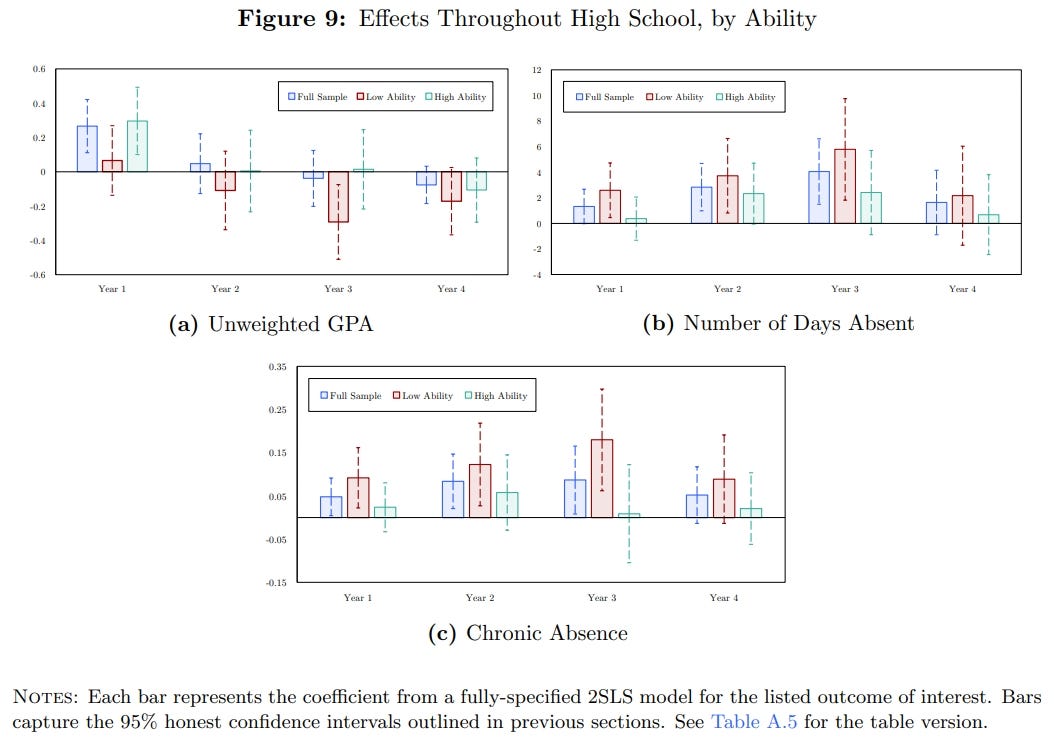

Indeed, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, in a 2023 paper, actually found that when academic standards are made more lenient, and grades artificially boosted, not only do worse performing students not do any better, but they actually attend school less, increasing absenteeism, perhaps because lower standards lead to less interest and engagement among students:

In response to widening achievement gaps and increased demand for post-secondary education, local and federal governments across the US have enacted policies that have boosted high school graduation rates without an equivalent rise in student achievement, suggesting a decline in academic standards. To the extent that academic standards can shape effort decisions, these trends can have important implications for human capital accumulation. This paper provides both theoretical and empirical evidence of the causal effect of academic standards on student effort and achievement. We develop a theoretical model of endogenous student effort that depends on grading policies, finding that designs that do not account for either the spread of student ability or the magnitude of leniency can increase achievement gaps. Empirically, under a research design that leverages variation from a statewide grading policy and school entry rules, we find that an increase in leniency mechanically increased student GPA without increasing student achievement. At the same time, this policy induced students to increase their school absences. We uncover stark heterogeneity of effects across student ability, with the gains in GPA driven entirely by high ability students and the reductions in attendance driven entirely by low ability students … [W]e find that increased academic leniency led to mechanical GPA gains among high ability students, but large effort reductions among low ability students. These heterogeneous effects compound over time and exacerbate gaps in student ACT performance. Therefore, the short-run gains of artificially raising high school completion rates may result in a permanent widening of long-run welfare gains, especially when lowered standards are not associated with any relative increase to human capital accumulation.

And sure enough, attendance at our local schools has plummeted as well, and has remained low long after the COVID pandemic ended.

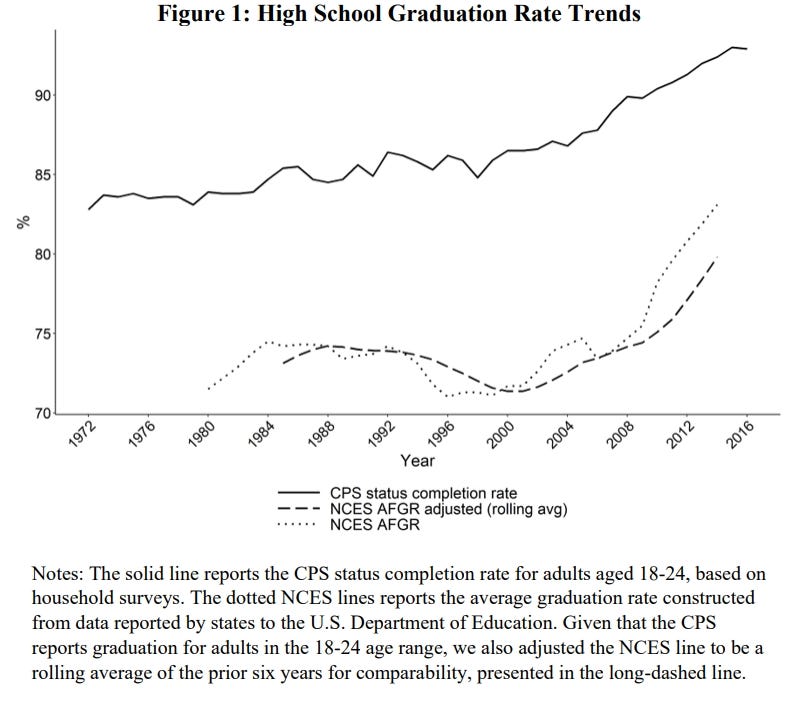

The lowering of math standards in California and elsewhere comes at a time when research is showing that requiring that a certain standard of objective knowledge and analytical ability be measured through standardized testing leads to increased knowledge. Researchers at the Brookings Institution found that accountability standards and testing required by the federal No Child Left Behind law led to genuine increases in learning, which in turn led to higher graduation rates:

High school graduation rates have increased dramatically in the past two decades. Some skepticism has arisen, however, because of the confluence of the graduation rise and the starts of high-stakes accountability for graduation rates with No Child Left Behind (NCLB). In this study we provide some of the first evidence about the role of accountability versus strategic behavior, especially the degree to which the recent graduation rate rise represents increased human capital. First, using national DD analysis [that is, difference-in-differences analysis, in which a researcher compares the change in outcomes in a (non-random) treatment group before vs. after treatment to the change in outcomes in a comparison group over the same time period (even though the comparison group never received treatment)] of within-state, cross-district variation in proximity to state graduation rate thresholds, we confirm that NCLB accountability increased graduation rates. However, we find limited evidence that this is due to strategic behavior. To test for lowering of graduation standards, we examined graduation rates in states with and without graduation exams and trends in GEDs; neither analysis suggests that the graduation rate rise is due to strategic behavior … Finally, we examine other forms of strategic behavior by schools, though these can only explain inflation of school/district-level graduation rates, not national rates. Overall, the evidence suggests that the rise in the national graduation rates reflects some strategic behavior, but also a substantial increase in the nation’s stock of human capital. Graduation accountability was a key contributor … Our analysis confirms that the positive correlation between the passage of NCLB and the rise in the graduation rate was due to graduation accountability. As we would predict, graduation rates increased most in the states that had a higher proportion of districts below the state graduation rate threshold; and in the districts (within states) that were below the threshold. The key contribution of the study, however, is showing that, despite the potential for significant distortion, at least some, and perhaps a substantial share, of the post-accountability graduation rate rise reflects human capital increases. Graduation rates increased faster in states that had graduation exams than those without; regular diplomas increased and GEDs decreased … In other words, we see limited evidence that the rising graduation rate is due to lower standards or less seat time.

But while we should all realize by now that rigorous standards incentivize learning, many schools are moving increasingly toward more lenient grading. As Frederick Hess writes:

America’s high schools have just endured a decade of dramatic grade inflation, according to a new study from ACT. This coincided with a decade of declining academic achievement, raising hard questions for those concerned about instructional rigor, inflated graduation rates, and the integrity of selective college admissions. Between 2010 and 2022, there was evidence of steady grade inflation among high schoolers. During that period, even as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (the “Nation’s Report Card”) recorded steady declines in reading, math, and U.S. history achievement, student GPAs climbed steadily higher. The average adjusted GPA increased from 3.17 to 3.39 in English; from 3.02 to 3.32 in math; from 3.28 to 3.46 in social studies; and from 3.12 to 3.36 in science. In 2022, more than 89% of high schoolers received an A or a B in math, English, social studies, and science … Easy A’s signal to students they don’t need to work hard to succeed, give parents a false sense of how their kids are doing, and allow students to graduate without essential knowledge or skills. They also undermine learning, as Brown University researchers have reported that students appear to learn more from teachers who are tough graders. This is hardly the first time we’ve seen evidence of grade inflation. These results reinforce a decades-long trend. For instance, the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress High School Transcript Study, issued by the National Center of Education Statistics, found that America’s students were getting better grades and (putatively) taking more rigorous classes than students a decade before, but actually learned less. In 2009, Mark Schneider, currently the director of the federal Institute of Education Sciences, found that the share of students completing algebra II grew one-third between 1978 and 200 and that average math GPAs rose markedly between 1990 and 2005 and, yet, student test performance in algebra I, geometry, and algebra II actually fell between 1978 and 2008. What’s driving this trend? For one thing, a number of education leaders, advocates, and experts appear to be increasingly uncomfortable with traditional notions of rigor or grading. [There is a] burgeoning push for “grading equity” (with districts eliminating the “zero”, eliminating penalties for late work, and allowing repeated re-tests) …

Regarding potential solutions, Hess writes:

What can we do about all this? … First, it’s crucial to appreciate that grade inflation isn’t a victimless crime. It sends a false signal to students and families, making it tougher for educators to encourage students, acknowledge hard work, or give honest feedback. It can mean that selective college admissions become more about connections and game-playing than about earned opportunity … Finally, colleges should take care to ensure they’re using credible measures of student preparation, which suggests a U-turn for all the schools that have ditched the SAT or ACT. Keep in mind that Harvard University’s Raj Chetty has reported that, contrary to the claims of anti-testing ideologues, selective colleges which embrace admissions testing are more likely to enroll low-income students than those which rely on grades, interviews, essays, and other similar inputs.

At the same time, as Jason Riley writes in the Wall Street Journal:

The progressive left’s response to these outcomes [racial disparities in educational outcomes] has been to wage war on meritocracy rather than focus on improving instruction. The goal is to eliminate gifted-and-talented middle-school programs, high-school entrance exams and the use of the SAT in college admissions. One defense of racial preferences in education for black students is that recipients, including those who go into teaching, are more likely to work in low-income minority communities after graduation. That’s true, but is it what economically disadvantaged students really need, more second-rate teachers? In his lively autobiography, “Up From the Projects,” the late economist Walter Williams related an incident from his teaching days at California State University, Los Angeles in the late 1960s. A black student approached him at the end of the course and said he needed a B to graduate. The student told Williams that he wanted to teach school in Watts, a predominantly black section of Los Angeles. Williams replied that Watts didn’t need any more mediocre educators. He added, jokingly, “If you’d said San Fernando Valley”—a predominantly white area back then—“I’d have given you the B.” Williams was appalled that many of his academic colleagues were holding their black students to lower standards. “There was no more effective way to mislead black students and discredit whatever legitimate achievements they might make than giving them phony grades and ultimately fraudulent diplomas,” he wrote. Sadly, the downstream effects of lax standards for black students that concerned him more than 50 years ago have only gotten worse.

Policies that lower educational standards can only hurt students, because the students denied the opportunity to learn more advanced material will be growing up in a global economy including others around the world who were not so isolated from academic challenge. As Condoleezza Rice and others wrote back in 2012, in a publication of the Council on Foreign Relations:

International competition and the globalization of labor markets and trade require much higher education and skills if Americans are to keep pace. Poorly educated and semi-skilled Americans cannot expect to effectively compete for jobs against fellow U.S. citizens or global peers, and are left unable to fully participate in and contribute to society. This is particularly true as educational attainment and skills advance rapidly in emerging nations.

As Rice and other write, this crisis of lowered standards amounts to a national security threat in the following ways:

[C]urrently, by the Department of Defense’s measures, 75 percent of American young people are not qualified to join the armed services because of a failure to graduate from high school, physical obstacles (such as obesity), or criminal records. Schools are not directly responsible for obesity and crime, but the lack of academic preparation is troubling: among recent high school graduates who are eligible to apply, 30 percent score too low on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery to be recruited. The military aims to recruit high school graduates who score high on the aptitude battery because graduating from high school and performing well on the battery, which assesses students’ verbal, math, science, and technical knowledge, predict whether recruits will succeed in the service … Today, less than a third of American students graduate with a first university degree in any science or engineering field. More than half of these students have studied social or behavioral sciences; only 4.5 percent of U.S. college students, overall, graduate with degrees in engineering. In China, by comparison, more than half of college students receive their first university degree in science or engineering. Six percent study social and behavioral sciences, and 33 percent graduate with a degree in engineering … Many U.S. generals caution that too many new enlistees cannot read training manuals for technologically sophisticated equipment.

In the following decade, as Patrick Brady and Mike Waltz write in the Wall Street Journal, the U.S. military has tended to make matters worse by watering down their own standards and emphasizing skin color and other immutable characteristics over merit:

The U.S. military faces a self-inflicted threat to its preparedness to deter, fight and win wars. An essential, battle-tested element of military culture—colorblindness—is being undermined. Unless the trend is reversed, our national security will be at increased risk. The reversal could be done at no cost, requiring only a policy decision and the reorientation of relevant training. Selflessness, which has been vital to the warrior ethos for generations, requires subordination of self and subgroup identity and the ability to regard teammates’ racial and ethnic differences as inconsequential. In the Army and Marines, sayings such as “We’re all green” or “We all bleed red” were part of training that transformed millions of diverse civilians into war fighters … But that ethic is under attack. At the Air Force Academy, cadets have been taught that the term “colorblind” is offensive and that it’s preferable to be “color conscious.” Rather than teach future military leaders that “colorblindness” is a cultural imperative, the Pentagon unnecessarily focuses on, and even elevates, race and maintains an obsessive focus on racial demographics. Worse, it uses racial preferences in officer accession programs and sometimes in command, promotion and schooling selections. Such practices aren’t merely antithetical to true selflessness and the law; they also threaten military cultural norms like unit cohesion and the forces’ “selfless servant warrior ethos.” Training that in earlier years was intended to ensure equal opportunity and dignity and respect for all has been displaced by diversity, equity and inclusion curricula …

As the Wall Street Journal writes:

The Department of Veterans Affairs has a gender gingerbread person. NASA says beware of micro-inequities. And if U.S. Army servicewomen express “discomfort showering with a female who has male genitalia,” what’s the brass’s reply? Talk to your commanding officer, but toughen up. These are details from hundreds of pages of diversity and inclusion training materials used by the federal government in 2021 and obtained under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Everyone in corporate life knows such training, lampooned in the second episode of the TV show “The Office.” Yet taxpayers might be curious how their money is being spent to instruct the federal workforce these days … Asked for its diversity training, the U.S. Army offered three modules on transgender policy, one for “Commanders at all levels,” another for “Special Staff,” and a third for “Units and Soldiers.” Notable is a series of vignettes that cover pronoun usage, urinalysis observation, and a serviceman who wants “to discuss his newly confirmed pregnancy.” … [O]ne lesson is that there is now a conveyor belt from academia to the diversity-industrial complex. The portmanteau “misogynoir” was coined in 2010 on a blog called Crunk Feminist Collective. Eleven years later it’s in a training for government workers. This type of re-education was accelerated by President Biden’s 2021 executive order directing agencies to “increase the availability and use of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility training.” It’s a form of political indoctrination intended to impose woke values on the vast federal bureaucracy and U.S. military.

The U.S. military used to be known for sticking to merit in the face of contrary trends, but now the military seems to be going the way of college campuses. As Frederick Hess writes:

The New York Times recently sparked a heated debate about academic rigor when it reported that New York University had fired a professor when students complained he was too tough. Maitland Jones, a professor of organic chemistry and a co-author of a respected textbook, was dumped by NYU after 82 students in Jones’ introductory organic chemistry course signed a petition saying the course was too hard and their grades too low. An NYU spokesman responded to the ensuing outcry by insisting that Jones had been “hired to teach, and wasn’t successful,” pointing to poor student evaluations and a lot of withdrawals from Jones’ class. Meanwhile, Jones asserted 60% of the final grades in his last course were actually A’s or B’s, only 19 of 350 students had failed and the real problem was that students simply didn’t study enough. University of Pennsylvania historian Jonathan Zimmerman, author of a terrific book on college teaching, offered a revealing window into the clash. Noting that Jones has taught at NYU since he retired as a Princeton professor in 2007, Zimmerman recalled that a relative who had taken the professor’s Princeton class had insisted “that Jones was the best teacher he ever had, hands down. ‘He was the person who taught me to think,’ the relative (wrote to Zimmerman) after Jones’s dismissal hit the press.” Is Jones an example of an uncompromising, overly demanding college culture? Or have colleges become so lax, and campus leaders so cowed by their students, that simply maintaining reasonable expectations can now put a professor’s job at risk? On that point, a new survey of 1,000 four-year college students by Intelligent.com offers illumination. While these kinds of surveys should always be treated with appropriate caution, the results are provocative, especially against the backdrop of the NYU’s dust-up with professor Jones. For starters, 87% answered that they’ve thought at least one class was too difficult and that the professor should have made it easier; 64% said this was the case with “a few” or “most” of their classes. While the students said they tended to respond by studying more or asking for help, 8% reported that they had filed a complaint against the professor. When it comes to challenging classes, 18% said the instructor should “definitely” have been forced to make the class easier (48% said “maybe”). The most eye-catching finding, though, was what the students reported about their work habits. Most said they’re making an effort in their studies, with 64% reporting that they put “a lot of effort” into school. But, remarkably, of the students who answered they’re putting in a lot of effort, a third said they devote fewer than five hours a week to studying and homework – and 70% said they spend no more than 10 hours a week on schoolwork. A decade ago, in “Academically Adrift,” NYU sociologist Richard Arum and University of Virginia sociologist Josipa Roksa raised concerns when they reported how little work many college students were actually doing. They found that students were spending, on average, only about 12 to 14 hours a week studying, a decline of about 50% from a few decades earlier.

Fortunately, at least so far, there’s one part of the military that has seemingly escaped the lowering of standards that too often goes along with Democratic educational politics: the system of military schools. As the New York Times reports:

On the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a federal exam that is considered the gold standard for comparing states and large districts, the Defense Department’s schools outscored every jurisdiction in math and reading last year and managed to avoid widespread pandemic losses.

Their schools had the highest outcomes in the country for Black and Hispanic students, whose eighth-grade reading scores outpaced national averages for white students. Eighth graders whose parents only graduated from high school — suggesting lower family incomes, on average — performed as well in reading as students nationally whose parents were college graduates.

What’s the key to educational attainment at military schools? Again, the New York Times:

[T]he [military] schools are inherently less political — big decisions come from headquarters — and therefore less tumultuous. Case in point: An academic overhaul that began in 2015 and has stuck ever since. Defense officials attribute recent growth in test scores partly to the overhaul, which was meant to raise the level of rigor expected of students.

Meanwhile, our own local school board here in Alexandria, Virginia, is busy pushing a wildly unpopular required program that apparently detracts from needed learning. The local high school newspaper recently ran an article on how unpopular and ineffective the "social emotional academic learning" is, reporting the following:

If you attend Alexandria City High School—or any ACPS school for that matter—you most likely are familiar with SEAL lessons, which are presented during the advisory period for all students to observe. Short for Social, Emotional, and Academic Learning, these lessons aim to educate students about social and life skills in a fun, engaging manner. Topics can range from mindfulness to motivation and empathy with the overall goal of promoting being a happy, healthy, and productive human being. This sounds like the ideal way to teach these topics with a maximum amount of engagement, but the facts simply don’t agree. SEAL lessons are widely unpopular among the students of ACHS. This dislike, however, is not just present among students but also among the teachers, with reports of teachers either skimming through the lessons or skipping them entirely. The only people who seem to believe, with good faith, that SEAL lessons are practical is the administration of the high school—but who even knows if they believe in them? Despite SEAL’s unpopularity, the administration still requires the lessons to be shown throughout the school during the advisory period on blue days ... Theogony created and distributed an online survey about SEAL’s content, relevance, and effectiveness to students. When asked their thoughts on SEAL lessons, one student answered, “They are not in touch with students and are often repetitive.” This often seems to be the case: it’s the perpetual problem of a point being repeated so much that it’s become exhausted and become completely devoid of meaning. Other students described them as “useless,” “ineffective time wasters” and even “stupid.” One even went so far as to say that those who support the SEAL initiative “bootlick the school board and a collective of out-of-touch parents.” ... In Theogony’s survey, the data about SEAL Lessons was not encouraging. When asked how often they pay attention to the lessons, 50% of respondents said they never do so, with an additional 25% saying they ignore the lessons more often than not. These two groups make up an overwhelming majority of 75% of respondents who, frankly, seem not to care much about SEAL ... The survey ... asked how effective SEAL lessons are, and a resounding majority of people— around 75%– said they were not effective at all. Moreover, only 5.2% of students said that they were very effective. And, when questioned about how often their teachers went through and taught the lessons, 25% of respondents said that their teacher never or almost never showcased the SEAL lessons. It’s safe to say that things are looking grim for SEAL lessons. Unfortunate as the current situation is, perhaps these results will act as a wake-up call for the School Board and the rest of ACPS. However, for now, it seems that the administration at ACHS remains staunch and set on continuing to distribute SEAL lessons to the masses at all costs.

(Over a month after that report came out in the local high school paper, I asked the school board member who lives on our street, at the bus stop, if she’d seen it. She said she hadn’t.)

As time goes on, knowledge only expands. But as that knowledge expands, more and more students are tending to learn less and less -- while too many adults (who should know better) are cheering them on as they march backwards to the tune of lower academic achievement.

Paul, Scarily, this is also a big problem in medical schools. Admission requirements have been massively lowered. It used to be the ability to handle the academics [as measured by previous work] and the necessary motivation to endure the rigors of caring for people -- now is Social Justice Warrior score, Demographic score, and "distance traveled" score. No one has any idea what these are which is convenient for deliberately non-colorblind admissions. And the admissions committee no longer even gets to see academic records -- "they have been approved if they get to the committee"...yeah...right.

Because many of the matriculants are now academically unqualified, grades have had to be eliminated (in all schools, everywhere) because otherwise the shape of the failing group (which is quite large these days using prior standards) becomes quickly obvious. Pass/Fail is so easy, since each time one sets the pass/fail point to make sure only a tiny percentage fail, irrespective of the absolute scoring.

The natural follow on, of course, is that national testing (the National Boards) have also moved to pass/fail -- it is just a propagation of inadequacy right down the line. Once you start with a significant number of students who have never had to learn much before medical school (and may not be capable of ever learning much) the slide just continues.

Of course, there are some marvelous students, too. But no one will ever know who they are. Residencies, which used to be another shot to select for the most capable students, now have to guess in almost every case. We have retreated to pictures (interviews) and crossed fingers. Really an advance, I guess...

The problem is these people all get licensed and then go out and kill patients. I know no academic of my cohort who will see any physician under 45 or 50 for just these reasons (unless we have trained them and know they are not in the bottom-feeding category).

These are far more immediate effects than long-term diminution of science research. These facts have impact in how medicine is practiced (the retreat to cookbook "hospitalist" is the most obvious example, but there are many others). And they likely contribute to the ever rising "excess deaths" numbers we are seeing. These are big, big deals. And they start early as you always point out.

Thanks for doing this.