Continuing this series of essays on teachers unions and their influence on American public education, this essay will focus on teacher tenure policies.

As Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

Teacher quality makes an enormous difference. Indeed, even if the quality variation across teachers is less stark, the consequences for kids can still be profound. As researchers Eric Hanushek and Steven Rivkin report, if students had good teachers rather than merely average teachers for four or five years in a row, “the increased learning would be sufficient to close entirely the average gap between a typical low-income student receiving a free or reduced-price lunch and the average student who is not receiving free or reduced-price lunches.” In other words, it would eliminate the achievement gap that this nation has struggled to overcome for decades. Boosting teacher quality would also have much broader effects on students generally, and on the whole of American society. As Hanushek notes, summarizing the research, “The typical teacher is both hard working and effective. But if we could replace the bottom 5–10 percent of teachers with an average teacher—not a superstar—we could dramatically improve student achievement. The U.S. could move from below average in international comparisons to near the top.”

As Frederick Hess reports, the need for excellent teachers is especially important in early school years:

One of the most compelling pieces of data produced by all of our testing is this: If a cohort of children is a year behind after 2nd grade, only 15 percent of school districts in the country can get that cohort caught up by the end of high school. It’s problematic that our entire accountability system focuses on the second half of K-12 education, when it’s too late to catch kids up if they’ve fallen behind.

Moe asks “are there enough bad teachers in the classroom, so that [union] rules of this sort [rules that protect not-so-good teachers] actually create problems for schools and kids?”:

The answer is yes. Indeed, teachers themselves are quick to say as much. In one Public Agenda survey, 58 percent of teachers said that, in their districts, tenure does not necessarily mean that a teacher has worked hard and proved herself to be good (only 28 percent said the opposite), and a full 79 percent indicated that at least a few teachers in their own schools fail to do a good job and are just going through the motions. In another Public Agenda survey, superintendents and principals were asked to rate various ideas for improving the nation's schools, and both gave their top rating to reforms “making it much easier to remove bad teachers—even those who have tenure.” There is plenty of other evidence, as well, that the “bad teacher” problem is a serious one. In 2004, for instance, Pennsylvania gave many of its veteran teachers basic tests of competence in the subject matters they were teaching. Half of the middle-school teachers in Philadelphia—and a stunning two-thirds of the middle-school math teachers—failed their competency test. How are the kids in Philadelphia supposed to learn math if their own teachers don't know math?

Teacher “tenure” rules are the rules that make it more difficult to remove ineffective teachers. For the very same reasons collective bargaining for police unions results in rules that end up retaining bad police officers (as explored in a previous essay), collective bargaining for teachers results in rules that end up retaining not-so-good teachers. As Moe writes:

The existence of tenure makes it very difficult to remove mediocre teachers from the classroom, and studies have shown that many teachers are well aware of the problem. Indeed, when my own survey asked teachers, “Do you think tenure and teacher organizations make it too difficult to weed out mediocre and incompetent teachers?” 55 percent of teachers said yes, including 47 percent of union members. Common sense would suggest that this situation can hardly be good for children and quality education. But tenure is also enormously beneficial for teachers, essentially guaranteeing them a job for life. Who wouldn't want that, if they were thinking only of themselves? This, it appears, is precisely what teachers do … [W]hen asked whether they would support a move to eliminate tenure, 77 percent of teachers said they are opposed. Again, while the opposition is stronger among Democrats and union members than among Republicans and nonmembers, all are opposed by big majorities. Teacher tenure, like the right to strike, is supported by a broadly based consensus—a consensus rooted in common interests … [Teachers] have “tenure” and—assuming they don't murder someone or molest a child or stop showing up for work—they are assured of being able to continue in their job for as long as they want. This is the case, moreover, regardless of how they perform in the classroom and regardless of how much their students learn. Here again, America's private sector workers can only dream of such a thing: a guaranteed, totally secure job … [Teachers] have a job that, once they get beyond the probationary period (which is usually three years) and are granted tenure, cannot in practice be taken away from them … The most basic rules are state laws allowing for teacher tenure. These laws … often do not even use the word “tenure.” They are couched in such terms as “continuing contracts” and “due process” and “permanent status,” and they set out procedures that must be followed if a teacher on a continuing contract is to be dismissed. These procedures tend to be complicated, involve multiple steps and appeals—to arbitrators, for example, or the courts—and entail a great deal of time and expense for any district leader who tries to dismiss someone. None of which is an accident. Moreover, because attempts to dismiss a teacher are based on evaluations of the teacher's performance, the states have also passed laws that deal in depth with the local evaluation process—often specifying what forms and criteria are to be used, who is to do the evaluating, how often, what other participants must be involved, whether a remediation program must be set up pursuant to an unsatisfactory rating, what the remediation program must consist of, what steps must be followed if the unsatisfactory performance continues, and so on … [A]ny administrators who attempt to dismiss a teacher are embarking on a process that is destined to be extremely costly and time-consuming. And even if they make the investment, they may well lose: for a minor departure from the labyrinth of procedural requirements can result in a legal judgment in the teacher's favor, regardless of the teacher's competence … The lesson is not lost on school principals. They know that, if they give a teacher an unsatisfactory rating, they are setting themselves up for a formal grievance by the teacher and the union and entering a path of endless hassles. Even if they survive the grievance, the rules will probably require a remediation program—and thus monitoring, reports, additional evaluations, the involvement of other participants, and so on, leading to still more hassles. And these are just the beginning of a long, costly, conflictual process. Leading where? To the teacher very likely being let off the hook … As the New Teacher Project observes, based on its own research, “School administrators appear to be deterred from pursuing remediation and dismissal because they view the dismissal process as overly time consuming and cumbersome, and the outcome for those who do invest the time in the process is uncertain … One consequence, of course, is that bad teachers are almost never dismissed. Another is that, in order to avoid getting on the path from the outset, principals have strong incentives to make a mockery of the teacher evaluation process by giving virtually all teachers—including the incompetent and mediocre ones—satisfactory evaluations. This simply guarantees that virtually all junior teachers ultimately get tenure and that, once tenured, almost no one ever gets fired. Everyone is doing a “good job.” Even in schools that are demonstrably horrible. Data on teacher evaluations and dismissals have traditionally been very hard to come by, and until recently the whole subject had been shrouded by a conspiracy of silence among educators and policymakers. But a few years ago an Illinois news reporter, Scott Reeder, broke new ground by launching a massive research project in which he reviewed every dismissal case of an Illinois tenured teacher over an eighteen-year period, filed 1,500 Freedom of Information Act requests with various government agencies, conducted hundreds of interviews, and collected data from every one of Illinois' 876 school districts. This research now stands as the single most in-depth study of teacher dismissals yet conducted. Here are its major findings: —The average cost of a dismissal case during this time period was at least $219,000, a forbidding figure that nonetheless understates the actual cost, because 44 percent of the cases were still pending at the time. —Over the eighteen years, fully 93 percent of Illinois school districts never even attempted to fire a teacher with tenure. Of the sixty-one districts that tried, only thirty-eight were successful. —In their formal teacher evaluations over the last decade, 83 percent of Illinois school districts never gave a tenured teacher an unsatisfactory rating. —More specifically, Illinois principals spent well over 1 million hours during the last decade carrying out some 477,000 evaluations, just 513 of which resulted in unsatisfactory ratings. This means that 99.9 percent of all tenured teachers in the state received satisfactory evaluations, and an infinitesimally small one-tenth of 1 percent received unsatisfactory evaluations. —Out of roughly 95,000 tenured teachers throughout the state, an average of only seven a year were dismissed over the entire eighteen-year period, and of the seven only two were dismissed for poor performance. (The rest were due to misconduct.) … Other recent studies provide additional evidence and tell the same story. An inquiry into personnel decisions in the New York City schools, for example, shows that just eight teachers out of a total teaching force of 55,000 were dismissed for poor performance in 2006–07: a dismissal rate of about one one-hundredth of 1 percent. Each case, on average, required twenty-five days of hearings and 150 hours of principal time and cost $225,000—hardly an incentive for administrators to take action. A 2009 study of Seattle finds that only sixteen teachers out of 3,300 received unsatisfactory evaluations, less than 1 percent. A 2009 study of Hartford finds the same thing, with less than 1 percent of all teachers rated as unsatisfactory. A 2009 Los Angeles Times study finds that 99 percent of city teachers received satisfactory evaluations in 2003–04 and that the district fires fewer than one in 1,000 teachers (one-tenth of 1 percent) in any given year for any reason, not just performance … By any stretch of the imagination, is this the kind of personnel system that well-intentioned people would design to provide kids with the best education possible?

As Michael Hartney writes in his book How Policies Make Interest Groups: Governments, Unions, and American Education:

As former Clinton White House advisor and Harvard education professor Tom Kane argued in the aftermath of a 2012 lawsuit challenging California’s teacher- tenure law: “Teachers have large and lasting impacts on the lives of children. The negative impact of an ineffective teacher is as large and lasting as the positive impact of a great teacher. It makes no sense to make tenure automatic after 18 months on the job. And it is indefensible for schools to be forced to lay-off great young teachers to make space for ineffective teachers with more seniority. Such laws are not in the interest of students, and hurt disadvantaged minority students disproportionately. I welcome the [trial court] judge’s ruling.”

Teachers unions essentially demand veto-power over decisions to fire bad teachers. As was mentioned in a previous essay:

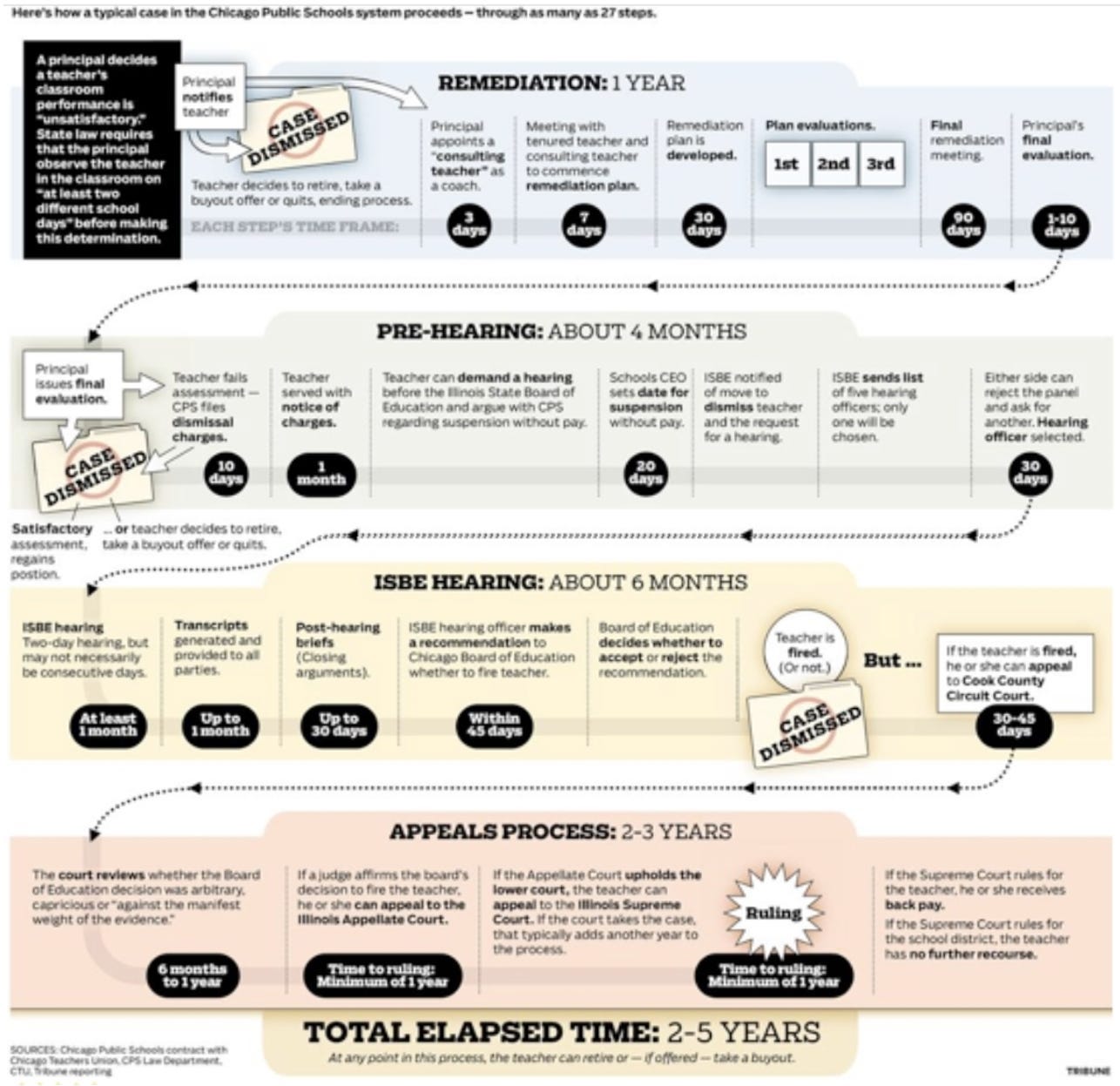

Teacher retention rules negotiated by teachers’ unions make it very difficult to fire bad teachers. As an example, here is a chart showing the process required for removing a bad public school teacher in Chicago.

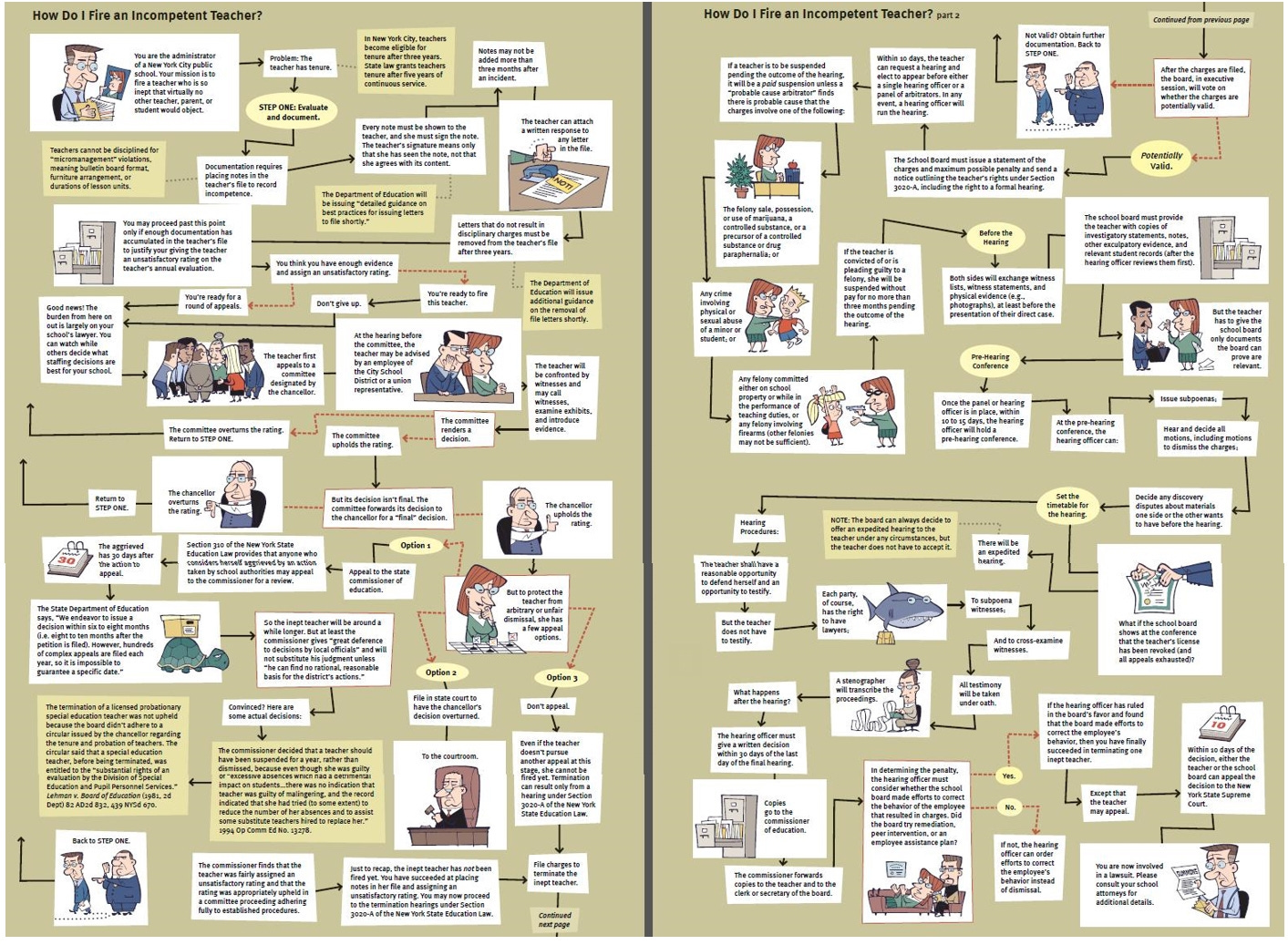

And below is a chart showing the same process required to remove a bad public school teacher in New York City.

As Moe writes, “Almost everywhere, in districts throughout the nation, America's public schools are typically not organized to provide the nation's children with the highest quality education. It is virtually impossible to get rid of bad teachers in New York City, but it's also virtually impossible in other districts too, regardless of where they are.”

As Mark Zupan writes in his book Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest:

Whereas 28.5 percent of Chicago Unified School District’s 11th graders met or exceeded Illinois testing standards, only 0.1 percent of teachers were let go for performance reasons from 2005 to 2008. In Chicago, as in other districts covered by collective bargaining agreements, teachers receive tenure after only a few years of probationary service and then are nearly impossible to fire. Indeed, merit has been increasingly eliminated from the [teachers union] compensation formula. In Illinois, a tenured teacher could not be dismissed for poor performance prior to 1985. Even after legislative reforms to promote greater accountability in 1985, however, it has remained extremely difficult to fire a tenured teacher. Of 95,000 tenured Illinois public school teachers, an average of only seven per year had their recommended dismissals approved by a state hearing officer in the eighteen years after the legislative reforms. Of the seven, on average only two were for performance reasons while the others were based on misconduct charges. The average cost per dismissal case was at least $219,000 – an amount large enough to make administrators think twice about attempting to fire a bad teacher. In the LAUSD, only 2 percent of the hired teachers are denied tenure after their two-year probationary period. Upon receiving tenure, an average of only eleven of the district’s 43,000 tenured teachers faced termination charges each year from 1995 to 2005. Most of these charges were for reasons other than performance issues. During the same time, the high school graduation rate for LAUSD [Los Angeles Unified School District] was barely above 50 percent. A union representative stated: “If I’m representing them [poorly performing teachers], it’s impossible to get them out … Unless they commit a lewd act.” It cost LAUSD $3.5 million in legal fees and took nearly a decade to try to dismiss seven teachers. Four ended up being dismissed, although two of them negotiated significant payout packages as part of their exit. In California, 0.002 percent of public teachers are dismissed for poor performance per year. In comparison, 1 percent of all public workers and 8 percent of private workers in the United States are let go each year for performance-based reasons. As noted by the movie Waiting for Superman, while one out of every fifty-seven doctors and one out of every ninety-seven lawyers lose their licenses, nationally, only one out of 1,000 teachers end up being dismissed on account of poor performance. The difficulty of firing poorly performing teachers who have tenure and are union members includes high costs to society, as portrayed by a New Yorker article by Steven Brill. Of the teachers hired in New York City, 97 percent are granted tenure after their third year of teaching. Moreover, until the advent of reforms introduced by Mayor Bloomberg in 2002, 99 percent of New York City’s tenured teachers received satisfactory ratings. Brill’s article focused on the 700 teachers assigned in 2009 to one of New York City’s so-called Rubber Rooms. Deemed to be unsuited for teaching, they still collected full pay and benefits, including summers off and the usual vacation days. Meanwhile, they spent their days solving crossword puzzles, sleeping, reading books, chatting with each other, and occasionally fighting over a folding chair. They did so while waiting two to five years for their cases to be heard by an arbitrator. The annual cost to the school district was $65 million in salary and benefits for the bad teachers alone. On top of that, the district had to hire substitute teachers, rent the Rubber Rooms to warehouse the bad teachers, and even pay $500,000 per year for security guards to keep the bad teachers safe – largely from each other while they were warehoused. Still, warehousing was better than trying to fire the educational lemons and thus challenge the teachers union, collective bargaining contracts, and state tenure laws.

Moe cites a telling survey that shows the value of teacher tenure rules to many teachers:

The first survey item asked, “Would you support or oppose a policy proposal that would eliminate teacher tenure, but in return provide teachers a 20 percent increase in salary?” … 33 percent agreed to go along with the deal … The upshot is that it took a salary increase of 50 percent to entice more than a majority (53 percent) of unionized teachers in collective bargaining districts to agree to give up tenure.

It may well be that so many teachers prefer tenure over higher pay because their compensation as it exists today is actually quite good, as was explored in a previous essay. Further context is provided by Zupan, who writes:

According to the NEA [National Education Association], the average base salary of public school teachers as of 2012– 2013 is $ 56,103. This figure can be misleading. The NEA does not tabulate the salaries for teachers covered by collective bargaining agreements (presumably higher due to the influence of union power) versus for those that are not. The NEA salary statistic does not incorporate factors such as fringe benefits, job security, and vacation time (typically three months per year). Nor does it account for the opportunity teachers have to earn more through taking on extra duties (tutoring or after-school assignments) or by cashing out unused vacation time, sick/personal days, and medical coverage … As of 2014, LAUSD teachers, who are covered by a collective bargaining agreement, earned a median of $75,504 after taking into account base salary, other duties, and cashed in vacation/ sick leave/personal days. The teachers earned an average of $21,000 in estimated pension and healthcare benefits beyond their regular pay, or a total annual compensation package of over $95,000. LAUSD teachers work 182 days a year (two days without students) and have twenty-two paid holidays. By comparison, a full-time worker in the private sector has two weeks of paid vacation, six paid holidays, and works 249 days annually. In addition, LAUSD teachers receive ten sick days per year and their workweek is 35 hours long when school is in session, compared to 40 hours for private-sector professionals. On average, urban public school teachers are absent 5–6 percent of all school days, almost three times as high as the absentee rate for the average professional or managerial worker in the United States. At the time of a successful union strike in 2012, the average Chicago public school teacher earned a reported $76,000 in salary and $15,000 in annualized benefits, compared to Chicago’s median household income (not counting annualized benefits) being $47,000. Through the strike, teachers secured a 17.6 percent pay increase spread over four years, the elimination of provisions allocating pay based on merit, and reduced weighting of student test scores in teacher evaluation formulas.

The value of tenure to teachers leads union leaders to vociferously oppose giving administrators the discretion to alter teacher salaries. As Moe writes:

When it comes to salary, the unions do not want administrators to have discretion. Above all, they don't want them to have discretion in paying good teachers more than mediocre ones and thus in making judgments about performance and productivity. As they frame the salary issue: all teachers do the same job (they teach), they are all competent (as documented by their formal teaching credentials), and they all deserve to get the “same” salaries based on simple criteria that anyone can meet. From the unions' standpoint, the “single salary schedule” is just what the doctor ordered, and virtually every collective bargaining contract has one. The typical salary schedule is a grid, with rows (“steps”) representing a teacher's seniority within the district, and columns (“lanes”) representing the teacher's educational degrees and extra educational credits (for example, from college courses or professional development classes). Any given teacher can easily and automatically be placed somewhere within the grid, in a box that specifies—by rule—exactly what the teacher's salary is … Data from the Schools and Staffing Survey show that virtually all American school districts have salary schedules with similar sorts of rules … From the standpoint of what is best for children, these salary rules make no sense at all. Research has long shown that, beyond the first several years, a teacher's seniority makes no difference for student achievement. In particular, teachers are not more effective at promoting student achievement as they gain additional experience. Similarly, research has consistently shown that simply having a master's degree, or accumulating additional course or professional development credits, does not make teachers more effective in the classroom. As a result, districts are saddled with compensation systems that are literally not designed to promote student achievement—and they are wasting millions of dollars that could be productively spent in other ways. According to researchers Roza and Miller, the unnecessary salary bump that school districts dole out for master's degrees alone cumulates to some $8.6 billion a year across the nation as a whole. The single salary schedule is a formula for stagnation. It guarantees that good, mediocre, and bad teachers are all paid the same, and it ensures that this prime source of incentives—which plays such a key role throughout the private sector—is almost entirely absent in the public schools … A study by Hoxby and Leigh has shown that the system's failure to reward talent has been a major factor over the years in pushing talented women out of public education and into other professions where their talent is rewarded … [T]he reality is that, in thousands upon thousands of districts throughout this country, salary schedules and across-the-board raises are the norm. The status quo prevails, and it is well protected. As a result, the American education system has been almost entirely unable to use pay as an effective tool for boosting teacher quality.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine how teachers unions oppose pay for performance programs -- and how in one city in a state that doesn’t allow collective bargaining for public school teachers, a pay for performance program has yielded very promising results.