What I Learned About “Social and Emotional Learning”

Have you come across the phrase “social and emotional learning” in your school district?

Many people aren’t aware of the latest catch phrases and acronyms embodying various concepts popular among the educational bureaucracy, which can often obscure what they really mean in practice. One example is what’s called “social and emotional learning,” an approach to teaching students. Wikipedia generally describes it as “an education practice that integrates social and emotional skills into school curriculum … In practice, social-emotional learning emphasizes social and emotional skills to the same degree as other subjects, such as math, science, and reading.”

As a report by the American Enterprise Institute noted, “The bland, pseudoscientific, and somewhat inscrutable term ‘social and emotional learning’ grafted onto the academic effort of schooling masks its nature, which heralds a reimagining of schools and teachers’ roles … Inherent in SEL is an under-discussed change in the role of the teacher, from a pedagogue to someone more closely resembling a therapist, social worker, or member of the clergy – no less concerned with a child’s beliefs, attitudes, and values.”

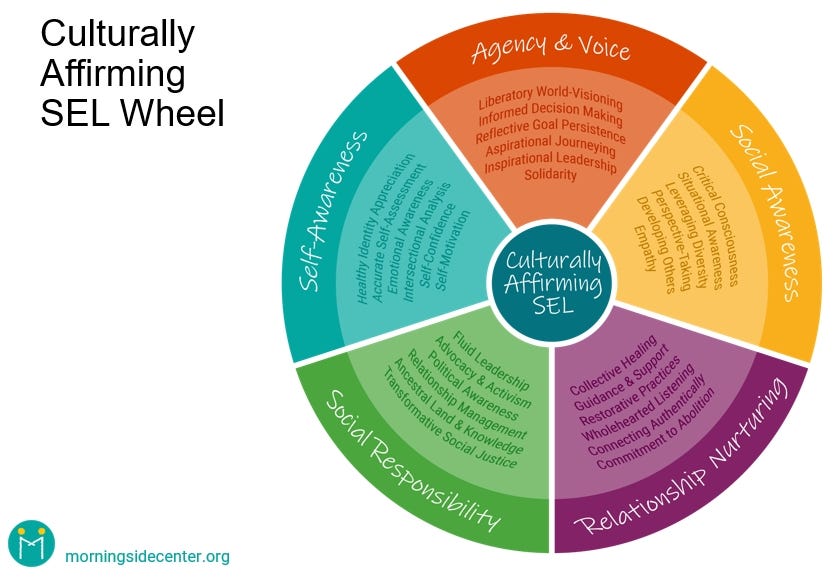

Beyond the vague descriptions, what sorts of things would students learn under the rubric of “social and emotional learning”? To find out, I signed up for a webinar on the issue sponsored by the American Federation of Teachers. It was hosted by a person who not only works for the American Federation of Teachers, but who also serves as a member of our local school board. The webinar was called “Culturally-Affirming SEL Wheel: Turning Toward Equity.” One of the presenters announced there would be a “big reveal” of a new definition of “social and emotional learning” that would have a “race-conscious” approach, which took the graphic form of a “delicious onion.”

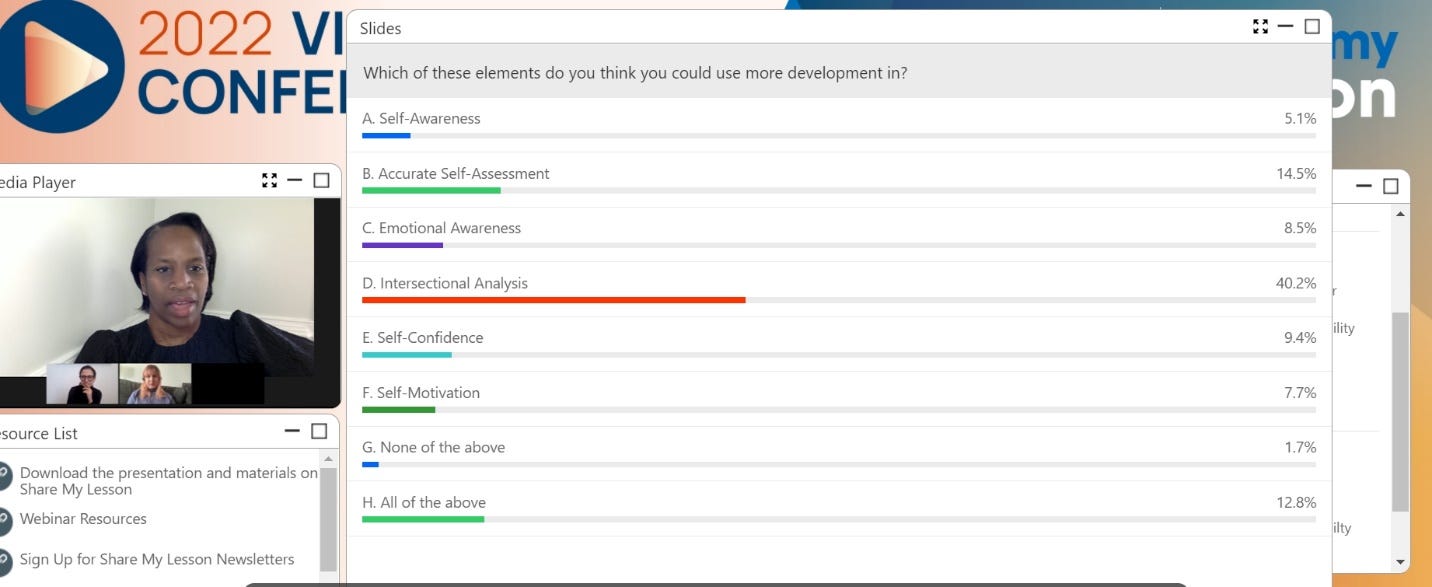

Based on audience participant interest, the presenters focused on an aspect of the approach related to self-awareness, and in particular the component on “Intersectional Analysis.”

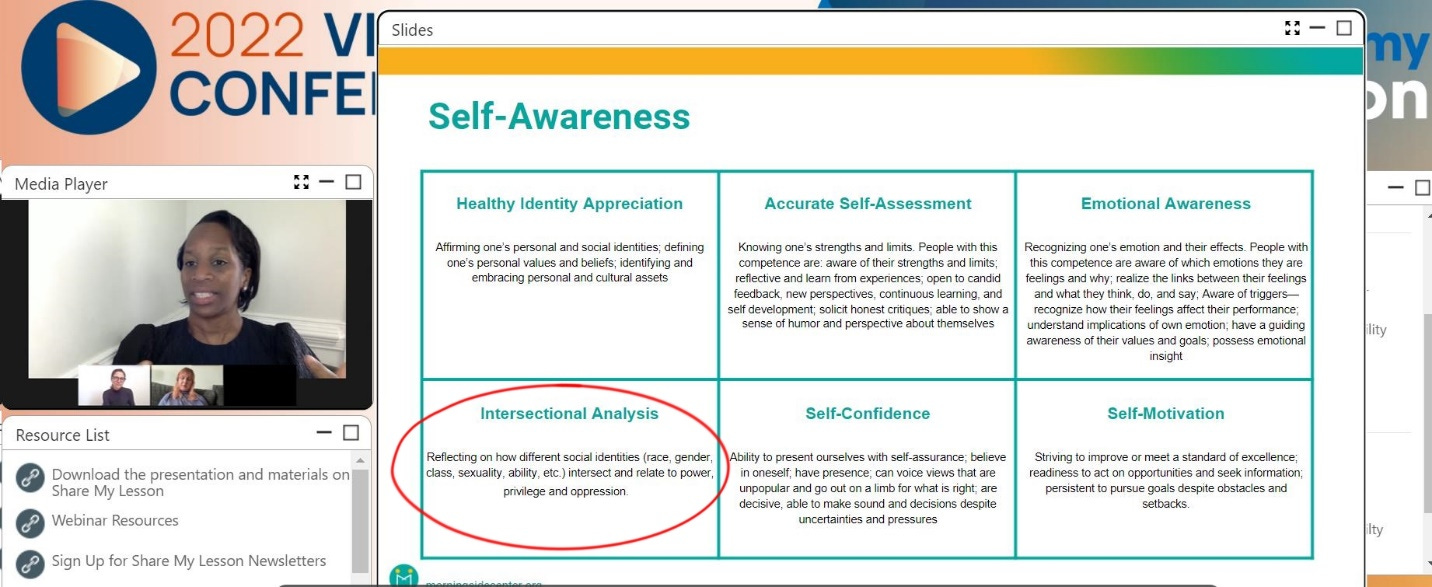

The presenters defined “Intersectional Analysis” as “Reflecting on how different social identities (race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, etc.” intersect and relate to power, privilege, and oppression.”

On the very same day of this webinar, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson was testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee as the first black woman nominated to the Supreme Court. She said during questioning that “I do not believe that any child should be made to feel as though they are racist or … that they are victims, that they are oppressors. I don't believe in any of that.”

But apparently the presenters of the webinar on “social and emotional learning” do believe that.

The academic concept of “intersectionality” is described by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in their book “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure." They write:

[A] variety of theories and approaches flourished on campus in humanities and social science departments that offered ways of analyzing society through the lens of power relationships among groups … One such theory deserves special mention, because its ideas and terminology are widely found in the discourse of today’s campus activists. The approach known as intersectionality was advanced by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, a law professor at UCLA (and now at Columbia, where she directs the Center on Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies). … Crenshaw’s important insight was that you can’t just look at a few big “main effects” of discrimination; you have to look at interactions, or “intersections.” More generally, as explained in a recent book by Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge: “Intersectionality as an analytic tool examines how power relations are intertwined and mutually constructing. Race, class, gender, sexuality, dis/ability, ethnicity, nation, religion, and age are categories of analysis, terms that reference important social divisions. But they are also categories that gain meaning from power relations of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and class exploitation.”

As one of the webinar presenters similarly described “intersectional analysis,” “When I speak of social identities, I want to break that down further … I’m talking about race, gender, class, sexuality, etc. and the ways that we’re not just one thing. They all intersect and overlap. And what we’re looking at when we’re talking about analyzing is thinking about our own identities and the identities of others and all those components and how they relate to issues of power, privilege, and oppression. So recognizing that my experience as a white woman is different than a woman of color in terms of power, privilege, and oppression.”

Power relations are certainly an issue we need to understand. Indeed, it’s at the root of all debates regarding fairness. But as Lukianoff and Haidt point out, such a relentless focus on race and other “identities” can lead to seeing each other primarily as members of different tribes, rather than sharing a common humanity, with disastrous results:

The human mind is prepared for tribalism, and these interpretations of intersectionality have the potential to turn tribalism way up. These interpretations of intersectionality teach people to see bipolar dimensions of privilege and oppression as ubiquitous in social interactions. It’s not just about employment or other opportunities, and it’s not just about race and gender. Figure 3.1 shows the sort of diagram that is sometimes used to teach intersectionality … (For simplicity, we show only seven of her fourteen intersecting axes.) In an essay describing her approach, [Kathryn Pauly] Morgan explains that the center point represents a particular individual living at the “intersection” of many dimensions of power and privilege; the person might be high or low on any of the axes. She defines her terms like this: “Privilege involves the power to dominate in systematic ways … Oppression involves the lived, systematic experience of being dominated by virtue of one’s position on various particular axes.” According to intersectionality, each person’s lived experience is shaped by his or her position on these (and many other) dimensions … [W]hat will happen to the thinking of students who are trained to see everything in terms of intersecting bipolar axes where one end of each axis is marked “privilege” and the other is “oppression”? Since “privilege” is defined as the “power to dominate” and to cause “oppression,” these axes are inherently moral dimensions. The people on top are bad, and the people below the line are good. This sort of teaching seems likely to encode the Untruth of Us Versus Them directly into students’ cognitive schemas: Life is a battle between good people and evil people. Furthermore, there is no escaping the conclusion as to who the evil people are. The main axes of oppression usually point to one intersectional address: straight white males.

Spending for “social and emotional learning” programs at public schools has increased dramatically over a short period of time, even as its ideological character has also changed significantly over the same short period. As Max Eden has testified before Congress:

The Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) sector has grown dramatically in a very short period of time. From November 2019 to April 2021, SEL spending grew by 45% to $765 million. It is likely to soon become – if it isn’t already – a billion dollar education industry. During that short time, the ideological character of SEL also changed substantially.”

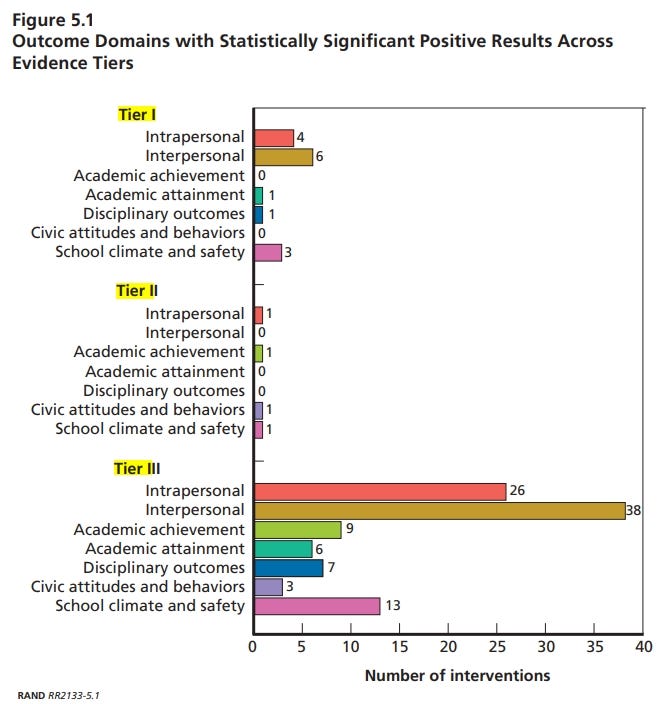

As Max Eden also pointed out in his congressional testimony, “A 2017 RAND Corporation review identified 68 SEL studies meeting three tiers of evidentiary rigor. No studies within the top tier of evidentiary strength demonstrated benefits to academic achievement. Only one study within the second tier found benefits to academic achievement. Studies categorized within the third, weakest, tier of evidentiary rigor showed benefits across a variety of metrics, and we could debate how much stock to put in them.”

Branding some students with the status of “oppressors” and others as “victims” based solely on their race, gender, or other immutable characteristics, as part of an official method of instruction, is a terrible idea. Do educational officials in your state or school district support it?