Agency – Part 4

A popular meme fails to recognize agency and leads to imposing equality of outcomes, regardless of individual choices.

Much current discussion in progressive circles about social and educational policy centers on producing equality of outcome based on racial demographics instead of individualized assessment based on particular circumstances. As Ian Rowe points out in his book Agency:

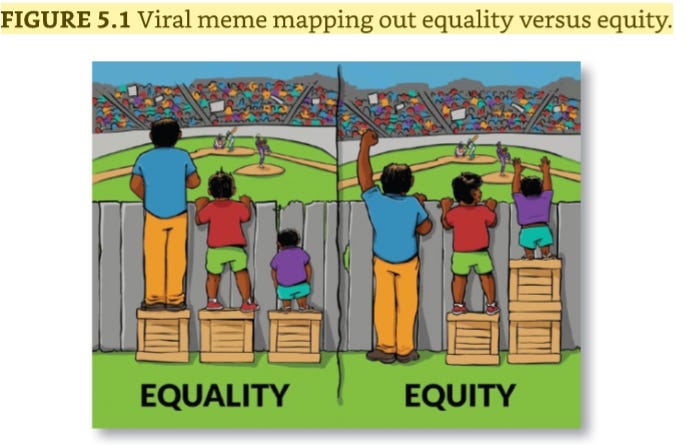

In the education world, few Internet memes are better known than the equality-versus-equity cartoon showing what happens when people of varying heights receive two different types of support (see Figure 5.1). Millions of educators have used this image to explain why equality is not enough and why we must pursue equity if our goal is a truly just society. For many, it is the end of the story. But is it? No. Equality is based on the idea that all humans are equal in fundamental worth and individual dignity. Equality means equal treatment. Each individual should have equal access to the same opportunities, no matter their race, creed, sex, or color and no matter their immutable characteristics (in this case, height). In the cartoon, equality means providing each of the three individuals with the same-sized box to stand on. But because not all three fans in the left frame can see over the fence, the question becomes what action should be taken so each has a real opportunity to see the baseball game. What steps should we take -- how should we distribute resources -- to ensure that everyone can see the playing field?

The problem lies with the image’s sole focus on equality of outcome and its simple correction of a problem caused by the immutable characteristic of unequal height, with no explicit or implicit examination of the influence of any personal circumstance or individual choice:

When these challenges -- not in heights [as represented in the cartoon meme], but rather in learning needs -- arise in a classroom, the answer would typically involve what is called “differentiated instruction.” Every student -- every human being -- possesses a unique mix of strengths and weaknesses that influence their attitudes and ability to learn. Good teachers recognize this and customize their teaching approach or assignments. Students receive differentiated instruction (in some sense, unequal treatment) so they have an equal opportunity to achieve or even surpass the same learning objectives. On a larger scale, leveling the playing field of opportunity might mean ensuring universal wi-fi access to all students, providing a laptop per child, or offering school choice so all parents, regardless of race, income level, or zip code, have the power to choose a great school for their child. Equity -- more precisely, the pursuit of equity -- is where things get tricky. While the equity fix presented in the cartoon’s right panel seems fairly benign at first glance, it is a far cry from using differentiated instruction to provide equal access to learning. [E]quity … as equality of outcome rather than equality of opportunity -- has become the unspoken real meaning for many of today’s educators, especially in the ever-lucrative industry of diversity, equity, and inclusion consulting. Darnisa Amante-Jackson, for example, is an educational and racial equity strategist and lecturer at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. She’s currently also CEO of the Disruptive Equity Education Project, which holds that “equity exists when disparities in the outcomes experienced by historically under-represented populations have been eliminated.” In other words, equity will only exist when group outcomes are equal … The problem is that guaranteeing this type of equity requires a process that ignores the individuals. It makes assumptions about group ability and artificially suppresses differences in outcomes that organically emerge from individual differences in attitudes and behaviors.

In his discussion of the problems with the “Equity” cartoon meme, Rowe focuses on the problem caused when one realizes some authority is going to have to enforce the equality of outcome:

To achieve equity, some authority must necessarily determine what resources a group should receive and who should receive them. The equity cartoon illustrates this point perfectly. In order to ensure that all three individuals can see over the fence, some entity has overseen the allocation or reallocation of resources. The shortest character’s boxes have been doubled while the tallest character’s one box is taken away entirely. And all this because of the difference between equality and equity. Addition is achieved through a perverse form of subtraction. As Karl Marx said, “From each according to their ability. To each according to their need.” … What makes the “equality-versus-equity” meme so disturbing is not simply its graphic representation of a dangerous ideology … [T]his latest educational fad erodes the personal agency of our children. Proponents of equity over equality see the image as a metaphor for the struggle between the inherently advantaged and the inherently disadvantaged, the “privileged” and the “nonprivileged,” the victimizers and their victims. There are no individuals in their world and no need for personal agency. There are only groups to count and sort. While the meme portrays equity for people of differing heights, its most frequent and damaging implementation occurs when social justice is sought in pursuit of racial equity. Imagine if all three figures were the same height. In fact, visualize three young people who are the same in every possible way except one. Then, in the name of racial equity, ignore every aspect of an individual -- attitudes, behavior, family structure, senses of humor, resiliency, agency, education level, and so on. In short, disregard every dimension of what makes an individual an individual and elevate one other factor above all others. Then conjure up a single variation based on nothing but skin color. One individual is white, one is black, and the third is Hispanic. That’s how proponents of racial equity view the world and its inhabitants. They never see the person. Through their “racial equity lens,” they see each of the three figures as a flattened representative of a group. Worse still, they see the black individual as a stand-in for an inherently victimized, structurally oppressed group and the white person as a stunt double for their inherent victimizer or structural oppressor.

When I was in college, I took a course on political and moral philosophy. One of the books assigned was Robert Nozick’s classic Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Part of that book always stuck with me, as it was probably the first time I’d been exposed to the idea that, no matter what outcome the government might want to impose on everyone, the role of individual choice can’t be ignored because as long as people are allowed any room for individual choice, those collective choices will inevitably end up disrupting the outcomes the government imposed initially. That part of the book is commonly referred to as Nozick’s “Wilt Chamberlain example” because it refers to a famous basketball player around the time the book was written.

Here's how the Wilt Chamberlain example goes. Assume, writes Nozick, that the distribution of things in society is enforced based on whatever principle you like – it could be equal ownership of property, equal distribution of education, or the equal distribution of anything else on whatever criteria you pick. Now imagine Wilt Chamberlain is an excellent basketball player, and very popular, and lots of teams compete for him to be on their team. Chamberlain eventually agrees to play for a team, on the condition that everyone attending the game puts 25 cents in a special box at the gate, the proceeds of which will go to Chamberlain. During the season, a million fans attend the team’s games, and Chamberlain gets $250,000. The result? Whatever the initial distribution of resources was in society before Chamberlain played, it’s now been disrupted, because Chamberlain now has $250,000 more than anyone else. Is the new distribution unjust? If you think it’s unjust, then you will presumably have to support a whole variety of laws that prevent people from exercising their individual choice (in the Chamberlain example, the choice of people as to what they want to pay for with their own money). The key is seeing how this example applies to all manner of systems that aim to equalize outcomes along any criteria.

For example, in the educational context, one might seek to guarantee equal educational outcomes, in a variety of ways. For example, one could require kids to study a certain amount of time every night (instead of doing whatever else they might have chosen to do instead) until a high level of equality of educational outcomes was achieved. But that would be very difficult to enforce, even if it were constitutional. In the alternative, however, one could simply lower standards to allow students to more easily achieve lower levels of equal outcomes. That would certainly be much easier to enforce. (Indeed, such a policy would not be an enforcement policy at all, but rather the abdication of any enforcement of standards.) And so that much easier approach will tend to be preferred by those who want to guarantee equality of outcomes in education.

And sure enough, at a local school board meeting earlier this year, some members of the board proposed to change school grading policy such that a student who didn’t submit their homework would not be graded a zero for that assignment, but rather their record would note the assignment was simply “not handed in.” While that controversial proposal was subsequently put off to another day, proponents of the proposal argued the current system of allowing grades of zero for “work not turned in” penalized students for something that might not be their fault, but rather the fault of other school personnel, parents, of other aspects of the student’s environment. Proponents of the proposal also argued that missed assignments are simply the “absence of data” on a student’s mastery of content, and because a score of zero indicates the student has no knowledge of content, using a zero for missed assignments when determining final grades will result in an invalid indicator of student mastery of content.

Of course, by the same (false) logic, “not showing up for work” is simply the absence of data on a worker's ability to do the work, and because docking pay indicates the worker has no ability to do the work, docking pay for failing to not show up for work when determining payment would result in an invalid indicator of a worker’s ability to do the work. The error in the analogy drawn by proponents of the grading policy is that such analogy fails to recognize that part of demonstrating mastery in a subject (through homework), just like demonstrating work at one’s job, requires actually submitting the homework (and actually doing the work).

One school member said (Ms. Simpson-Baird at 1:04:50-minute mark):

When I first read this policy [of prohibiting a grade of zero for homework not turned in] I was super excited about it. I very easily saw these connections to the work of Joseph Feldman on equitable grading … I’m familiar with several of the school divisions that have already gone in this direction like Fairfax and Albermarle, and I see these proposed changes very clearly linked to our mission and our values and our racial equity work, and those are all values that I hold, you know, true for myself, too … I was prepared tonight to, like, make a suggestion around the “not handed in” clause and then run with this and get excited and, you know, start implementing it, but then I started talking to our educators who will be tasked with implementing these changes and their responses made it so clear to me that we are just not there yet. We’re not, we have not done the work … to bring people along so that they understand how this is so inherently rooted in everything that we’re trying to do, and it is the core of our mission, and, what we’re trying to get done … We can get there.

So Ms. Simpson-Baird says she will still support the changes eventually because they align with the school “equity” plan. She just thinks the board needs more time to “bring people along” to support her “exciting new program” … of lowering standards. Note that Ms. Simpson-Baird says that she was excited about the proposal because it reflected the work of Joseph Feldman’s proposed policy on “equitable grading.” But as researchers point out, there is grave cause for concern regarding Feldman’s proposals:

[O]n Page 111 of his [Feldman’s] book, he lists “penalizing for lateness (tardiness or submitting work past the deadline)” as a biased practice. Then, on Page 115, he writes, “Reducing grades for late work both creates inaccuracy and violates our bias-resistant Driving Principle.” He specifies no alternative penalties, other than on Pages 213–14, where he mentions that “students may need formal reflections” on lateness—which he may believe is sufficient to address these problems. Feldman also told you that prohibiting penalties for cheating and plagiarism is not part of his program. But “punishing cheating in the grade” is listed as another inequitable practice in his book, again on Page 111. In fairness, he does suggest some mild nongrade penalties, but they are poorly defined, such as “withdrawing some privilege or responsibility,” and he does not address how to implement them equitably. The bottom line is that his system prohibits grade penalties for cheating without putting any real deterrent in their place. Additionally, Feldman said in your first exchange that the idea of “endless retakes” was “hyperbolic shorthand.” Yet on Page 175 of his book, he says: “If a student’s mastery of the content is important for success on future content, then you might want to give retakes until students have demonstrated necessary understanding.” Astonishingly, he proclaims that “Most schools and districts allow grade changes after a semester is over, so doesn’t that explicitly allow, perhaps invite, a student who wants to learn unmastered material to continue learning beyond the term and have her grade reflect that learning?” … But perhaps the most troubling of Feldman’s claims is his repeated assertion that his program does not contribute to grade inflation. In fact, throughout Chapter 7 of his book, Feldman supports “minimum grading,” more commonly known as the “no-zero” policy. With this practice, teachers are prevented from assigning students any grade under 50 percent, often regardless of whether the student attempted the task. If a student who would otherwise have earned a zero, a 25, or a 45 suddenly gets a 50, that will necessarily increase (read: inflate) that student’s grade without changes in the quality of the student’s work. Feldman is free to argue that these policies are worth considering, but he cannot argue that they do not contribute to inflating grades, particularly for lower-performing students. Most people would recognize that removing penalties for late work and cheating is also likely to inflate grades. The research base on which Feldman’s work rests is thin. As far as we can tell, his assertion that his program “decreases both grade inflation and grade deflation” relies on a single analysis that his company conducted internally for use in its marketing materials. Feldman said that the document shows that “teachers who use equitable grading practices assign grades that are closer to students’ scores on standardized tests.” But it is impossible to evaluate this claim based on the document he cites, which includes very little data, fails to define key terms (e.g., “assessment consistency”), and offers no information about the statistical models that produced the results. (Incredibly, considering the nature of this document, Feldman criticized us for not including it in our review of the research on grading practices.) Based on our reading of the document as researchers, it is entirely possible that grades and test scores are less aligned after their program. What we do know is that even Feldman’s company’s own analysis offers exactly zero evidence that students learned more after the implementation of his program. Perhaps his most harmful recommendations are those that remove mechanisms to discourage student procrastination. Feldman argues against not only late penalties but also grades for homework and, in fact, grades for any practice assignments. Virtually every teacher knows that students learn more when they have some shorter-term, smaller-bite, lower-stakes assignments. But those assignments should not have zero stakes, or students will quickly realize that they are effectively optional. Enforcing deadlines and limiting retakes are critical pedagogical tools. All of this, in addition to no-zero policies and failing to dock points for late work, lower expectations and academic standards, despite Feldman’s confident assertions to the contrary. In the words of one public school teacher, equity grading “encouraged [students] to do the minimum.”

So-called “equitable grading” policies are overwhelmingly disliked by teachers. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Tolerating poor or unfinished homework in the name of “equity” gained traction during the Covid years. It’s more prevalent in “majority-minority schools,” according to the survey of nearly a thousand K-12 public teachers, published Wednesday by the Fordham Institute. Some 58% of teachers in those schools reported the use of at least one equitable policy. The good news is that teachers hate it: 81% said a no-zeros policy is “harmful to academic engagement,” including 80% of “teachers of color,” the Fordham report says. Some of the quotations from surveyed teachers are unsparing: “Being given a 50 percent for doing nothing seems to enable laziness.” “Ridiculous.” “Insulting to the students who work.” … A majority of teachers, 56%, said a policy of no late penalties is harmful, compared with 23% who liked that.

Would such an “equitable grading” program that lowered standards encourage students to exercise more personal responsibility, or less? A recent study on the effects of a similar policy (a policy of eliminating grades and moving instead to a pass/fail grading system) indicates the latter. The authors of the study found as follows (emphasis added):

In Fall 2014, Wellesley College began mandating pass/fail grading for courses taken by first-year, first-semester students, although instructors continued to record letter grades. We identify the causal effect of the policy on course choice and performance, using a regression-discontinuity-in-time design. Students shifted to lower-grading STEM courses in the first semester, but did not increase their engagement with STEM in later semesters. Letter grades of first-semester students declined by 0.13 grade points, or 23% of a standard deviation. We evaluate causal channels of the grade effect—including sorting into lower-grading STEM courses and declining instructional quality—and conclude that the effect is consistent with declining student effort.

The researchers added that

This interpretation is bolstered by descriptive evidence from a faculty survey in 2017, which provided detailed examples of how students reduced effort, including attendance and course preparation … instructors commented that student motivation and effort were lower in first-semester sections of their introductory courses, relative to similar settings in pre-policy years and relative to non-first-semester students. As examples, instructors mention (1) course attendance; (2) the level of preparation for class discussions; (3) the quantity and quality of students’ note-taking; (4) commitment to tasks such as peer review of writing assignments; (5) the take-up of options to re-write papers for a higher grade; and (6) exam preparation and performance. Some instructors commented specifically that lower effort was more pronounced in the second half of the semester, possibly when students felt greater assurance of reaching a passing threshold.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how a simple peg board illustrates our changing paths in life.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.