In the previous essay, we examined how just small reductions in the chances someone might achieve one criterion or other necessary for success can have large negative (or positive) impacts on their overall chances of success. In this essay, we’ll examine one particular set of criteria that has proven to have such predictive power for success that it’s been given its own name: The Success Sequence.

As Ian Rowe has testified before Congress:

a range of studies have identified “toxic levels of wealth inequality,” especially between black and white Americans. According to the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the wealth gap between Black and white Americans at the median — the middle household in each community — was $164,100. The median Black household was worth only $24,100; the median white household, $188,200 … For some, this gap is vibrant proof of a permanent and insurmountable legacy of racial discrimination … But [t]he same 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances that shows the average black family has one seventh the wealth of the average white family also shows the reverse when family structure is considered. Indeed, black households headed by two married parents have slightly higher wealth than the median net worth of the typical white, single-parent household (Figure 1).

And when education is considered, on an absolute basis, the median net worth of two-parent black households is nearly $220,000 and more than three times that of the typical white, single-parent household. See the chart below.

Moreover, the 2017 report The Millennial Success Sequence finds that a stunning 91 percent of black people avoided poverty when they reached their prime young adult years (age 28–34), if they followed the “success sequence”—that is, they earned at least a high school degree, worked full-time so they learned the dignity and discipline of work, and married before having any children, in that order.

As Rowe writes in his book Agency:

[T]he Success Sequence [is] a series of life decisions that involves first graduating from high school, then securing full-time work, then getting married, and then having children. Among millennials, evidence shows that following this series of decisions creates a 97 percent chance of avoiding poverty. Despite concerns that imparting this information to young people might be viewed as condescending, overwhelmingly large majorities of all Americans (77 percent) and American parents (76 percent) support “teaching students that young people who get at least a high school degree, have a job, and get married—before having children—are more likely to be financially secure and to avoid poverty in later life.”

A recent study found that:

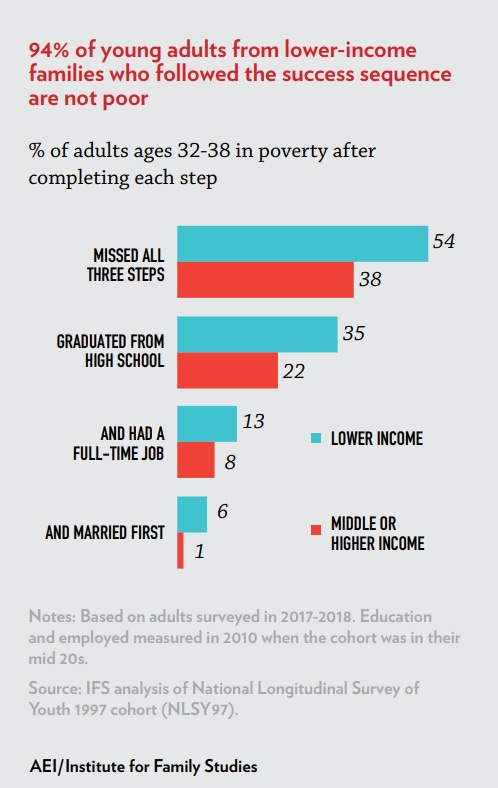

Among Millennials who followed this sequence, 97% are not poor when they reach adulthood … Critics of the success sequence often point out that it ignores the “obstacles individual efforts can’t always overcome.” There is no question that structural disadvantages make it more difficult to follow the three steps of the sequence. But that is also why it matters: Young adults who manage to follow the sequence—even in the face of disadvantages—are much more likely to forge a path to a better life … The vast majority of black (96%) and Hispanic (97%) Millennials who followed this sequence are not poor in their mid-30s (ages 32 to 38), as is also the case for 94% of Millennials who grew up in lower-income families and 95% of those who grew up in non-intact families. Moreover, for those who do not have a college degree but only finished high school and who work and marry before having children, 95% are not poor by their mid-30s.

The study authors also found that

The encouraging news is that with completion of each step of the success sequence, the racial gap narrows rapidly. For Millennials who followed all three steps, only 4% of blacks and 3% of Hispanics are poor by their mid-30s. Stunningly, the racial gaps in poverty are almost closed.

Low-income young adults who follow the Success Sequence also do well:

After following all three steps, 94% of Millennials who grew up in the bottom third of the income distribution are not poor by their mid-30s. Similarly, the success sequence offers a way out of poverty for young adults who have grown up in non-intact families. Among Millennials who didn't grow up with both biological parents but followed all three steps of the success sequence, 95% are not poor as adults.

Nor is college necessary to use the Success Sequence to escape poverty:

Even though having a college degree is associated with many benefits in life, Millennials who complete the success sequence but only have a high school education have a much lower risk of poverty as adults. Fully 95% of high school educated Millennials who completed the success sequence are not poor by the time they are in their 30s. Moreover, 82% of Millennials who completed the success sequence but didn’t pursue a college degree are in the middle or higher-income bracket by the time they are in their 30s.

Of course, people shouldn’t be coerced into doing any of the things that compose the elements of the Success Sequence. But they should be given this data so they can make their own informed decisions going forward. And students should be informed of the data that indicate “problems with the fashionable blame-the-system vision or powerlessness narrative.” As Rowe writes:

One is that it does not stand up to scrutiny. It’s a false narrative that often masks the hypocrisy of its most vocal advocates. Take that $164,100 wealth gap between black and white Americans in the Federal Reserve survey. When factors other than race are considered, the picture changes dramatically for both blacks and whites. According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, the median net worth of a two-parent, college-educated black family is $219,600. For a white, single-parent household, the median net worth is $60,730. While the racial wealth gap is $164,100 for whites over blacks when race is considered alone, when family structure and education are included, it is $158,870 in favor of blacks over whites. Individual choices do make a difference.

Schools themselves can only do so much to improve a child’s life prospects. As Rowe writes:

In 1966, the U.S. Office of Education commissioned the landmark Equality of Educational Opportunity survey to study the “lack of availability of equal educational opportunities” for minority children. James Coleman, the noted sociologist and civil rights advocate who in 1963 had been arrested along with his family for demonstrating outside an amusement park that refused to admit African Americans, led the study … The 700-page Coleman Report drew on data from more than 645,000 students and teachers in 4,000 U.S. public schools. One of its most controversial findings was that family background, not schools or race, explained most of the achievement gap between America’s white and black students. As the report stated, “One implication stands out above all: That schools bring little influence to bear on a child’s achievement that is independent of his background and general social context; and that this very lack of an independent effect means that the inequalities imposed on children by their home, neighborhood, and peer environment are carried along to become the inequalities with which they confront adult life at the end of school.” Remarkably, the Coleman findings have stood up for more than fifty years. In fact, a group of academics organized at Harvard even tried to disprove the report but their collective re-analyses reaffirmed Coleman’s fundamental thesis: “Schools appeared to exert relatively little pull—explaining only 10 to 20 percent of the variability in student outcomes—while family background, peers, and students’ own academic self-concept explained a much larger amount.”

As I wrote previously, “The much greater influence of the time parents spend with kids over the time kids spend in school as it relates to kids’ future success derives from the fact that each year consists of about 6,000 waking hours and children in America, on average, spend only about 1,000 of them in school (that is, 16% of their waking hours). The rest of the time is spent with their families and communities.”

Still, society will be less likely to get even that 10-20% improvement from school influence, as determined by the Coleman Report, if schools don’t recognize agency in the students themselves. And it’s even more important that schools teach the Success Sequence when students might come from homes that don’t demonstrate it by example. Regarding family structure, Rowe writes:

Family matters. More specifically, the structure and stability of the family within which a child is raised matters monumentally in the acquisition of agency … As Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution says, “Social policy faces an uphill battle as long as families continue to fragment and children are deprived of the resources of two parents.”

In the absence of a stable, two-parent family, it’s even more important that school leaders impart a sense of agency in kids who might not be imparted with that sense otherwise. If school leaders reject accountability based on a student’s perceived external life circumstances and provide no accountability of their own within the school system, that will only enlarge the agency-free void in which students can get lost. As Rowe writes, “Agency is accessible to everyone. But too often young people’s efforts to develop agency are thwarted, sometimes tragically, by the very people and institutions with the power and moral responsibility to propel their lives forward.”

The Success Sequence is a concept even those who haven’t followed it themselves see as valuable advice for their own children. Rowe writes:

My conversations with single parents in the community revealed that, far from being insulted, these parents welcomed the idea that schools would have the courage to speak to their children about better life-course decisions. Indeed, in a study conducted in 2021 by the American Enterprise Institute, seven in ten respondents who had not graduated high school, were unmarried parents, or were currently not working—supported teaching students that young people who get at least a high school degree, have a job, and get married before having children are more likely to be financially secure and avoid poverty in later life … After decades of working to revitalize our nation’s most challenging neighborhoods, I will share one of the most important lessons I have learned: There is nothing more lethal than a good excuse for failure. When a person is exempted from any personal responsibility for control of their life, you deprive them of the privilege and opportunity to craft solutions to improve their own condition.

Rowe suggests that “The Success Sequence could be taught as one of many possible decision pathways in a probability or statistics class. This would allow kids to explore data indicating how various life decisions differentially affect their likelihood of achieving economic prosperity in adulthood.” As Frederick Hess writes, “Americans intuitively support notions of mutual responsibility, with nine in 10 adults saying responsibility for one’s actions is a key component of what it means to be an American. This shouldn’t be a hard sell.”

Probability is indeed an important concept for kids to grasp early in life. Too often, the predictive power of the Success Sequence has been ignored by school leaders, and other risks have been grossly exaggerated, sometimes for political purposes. The history of risk assessment, and its modern politicization, will be explored in the next series of essays.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.

Paul, I sound like a broken record. Your pieces are uniformly enlightening and well done. I just wish you had more subscribers. They will come, but should come faster, IMHO. Thanks for this labor of love.