Uncertain Climate Predictions and Certain Energy Progress – Part 4

The media’s “telephone game” turns uncertainty into apocalypse.

Wikipedia describes a common children’s game, called the “telephone game” as follows:

Players form a line or circle, and the first player comes up with a message and whispers it to the ear of the second person in the line. The second player repeats the message to the third player, and so on. When the last player is reached, they announce the message they heard to the entire group. The first person then compares the original message with the final version. Although the objective is to pass around the message without it becoming garbled along the way, part of the enjoyment is that, regardless, this usually ends up happening. Errors typically accumulate in the retellings, so the statement announced by the last player differs significantly from that of the first player, usually with amusing or humorous effect. Reasons for changes include anxiousness or impatience [or] erroneous corrections …

When it comes to predictions of climate change, the popular media plays the telephone game, with even more varied reasons their pronouncements differ so wildly from even the very reports they claim to describe.

In his book Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, Steven Koonin sets out some statements about climate science from both the research literature and government reports that could start a round of the telephone game:

both the research literature and government reports that summarize and assess the state of climate science say clearly that heat waves in the US are now no more common than they were in 1900, and that the warmest temperatures in the US have not risen in the past fifty years. When I tell people this, most are incredulous. Some gasp. And some get downright hostile. But these are almost certainly not the only climate facts you haven’t heard. Here are three more that might surprise you, drawn directly from recent published research or the latest assessments of climate science published by the US government and the UN:

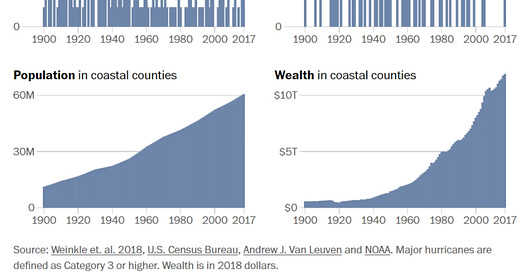

• Humans have had no detectable impact on hurricanes over the past century.

• Greenland’s ice sheet isn’t shrinking any more rapidly today than it was eighty years ago.

• The net economic impact of human-induced climate change will be minimal through at least the end of this century [and]

• the global area burned by fires each year has declined by 25 percent since observations began in 1998.

Regarding hurricanes, as the Washington Post reports:

The disaster data, maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has featured in multiple government reports on global warming. The Biden Administration has referenced it at least seven times to help make the case for climate policies. Members of Congress cited it in a bill to curtail the use of fossil fuels. Last year’s National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report on climate change, showed the disasters on a map under the heading “Climate Change Is Not Just a Problem for Future Generations, It’s a Problem Today.” But according to disaster experts, former NOAA officials and peer-reviewed scientific studies, the chart says little about climate change. The truth lies elsewhere: Over time, migration to hazard-prone areas has increased, putting more people and property in harm’s way. Disasters are more expensive because there is more to destroy.

But at the end of each telephone game session, the results are the headlines we’ve become used to, along the lines of “Extreme Climate Change Has Arrived in America.” How does this happen? As Koonin explains:

Most of the disconnect comes from the long game of telephone that starts with the research literature and runs through the assessment reports to the summaries of the assessment reports and on to the media coverage. There are abundant opportunities to get things wrong—both accidentally and on purpose—as the information goes through filter after filter to be packaged for various audiences. The public gets their climate information almost exclusively from the media; very few people actually read the assessment summaries, let alone the reports and research papers themselves. That’s perfectly understandable—the data and analyses are nearly impenetrable for non-experts, and the writing is not exactly gripping. As a result, most people don’t get the whole story.

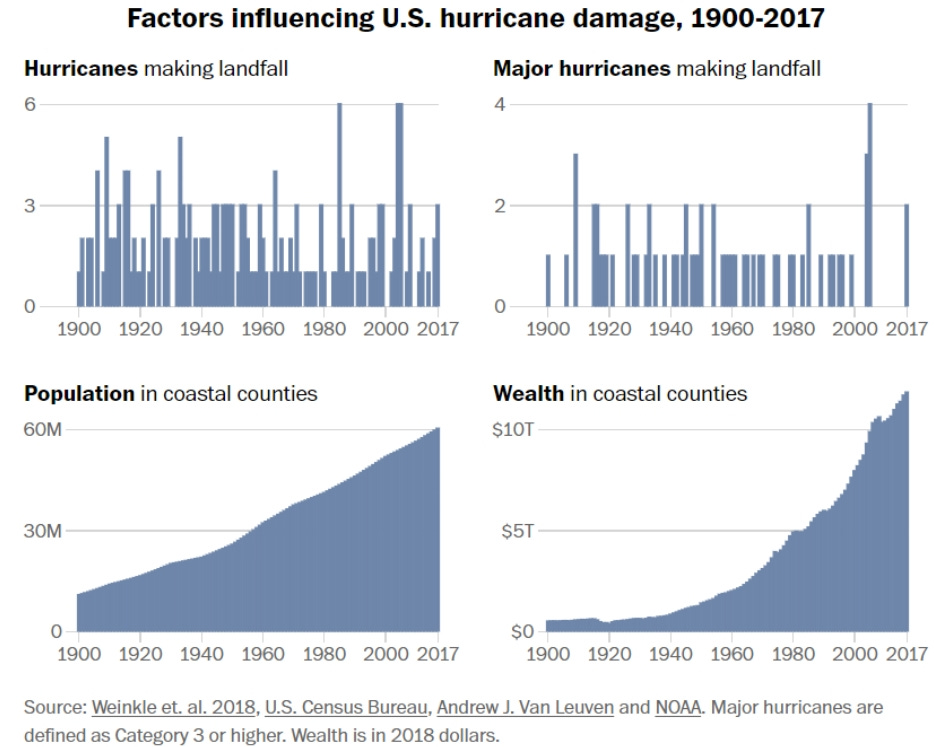

The whole story has to include things like the following. While we can all agree the Earth has gotten warmer over the past several decades, as Koonin writes:

The record highs clearly show the warm 1930s, but there is no significant trend over the 120 years of observations, or even since 1980, when human influences on the climate grew strongly. In contrast, the numbers of record daily cold temperatures decline over more than a century, with that trend accelerating after 1985. These two panels together show something that is completely contrary to common perception—that temperature extremes in the contiguous US have become less common and somewhat milder since the late nineteenth century.

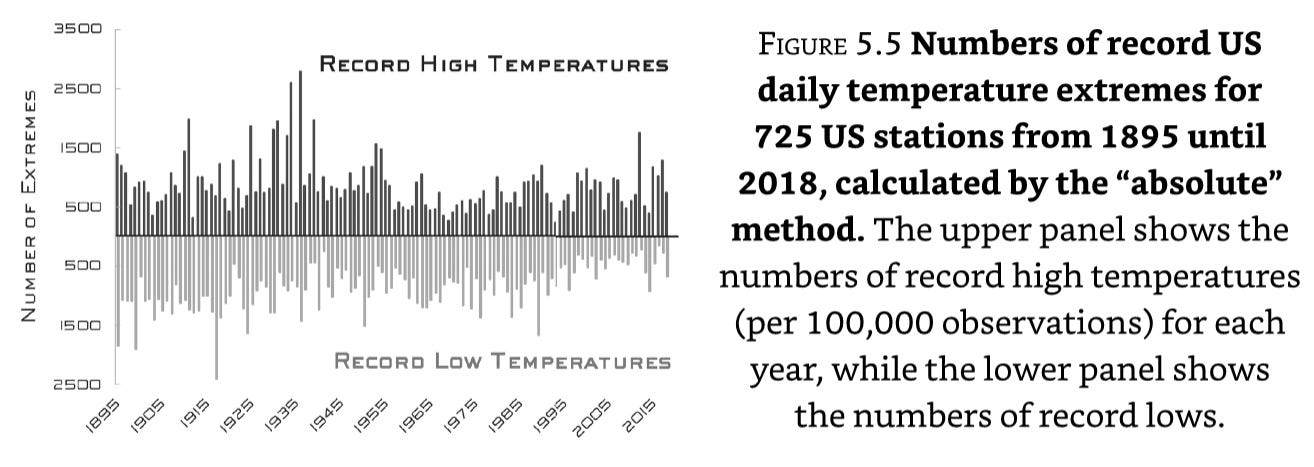

Regarding rainfall:

US precipitation has indeed risen a bit overall, but the fact that it varies over both years and location much more than the trend itself makes it hard to draw any solid conclusions about the relative roles of human influences and natural variability …

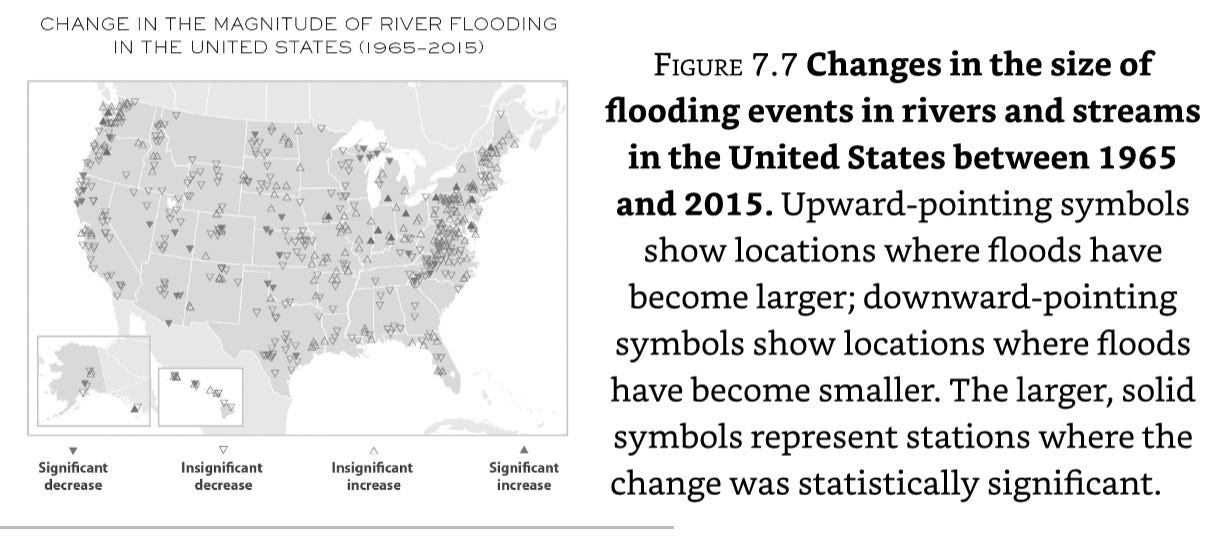

The modest changes in US rainfall during the past century haven’t changed the average incidence of floods. However, trends in flooding vary across the country, with some locations experiencing increases and some decreases, as seen in Figure 7.7, which shows location-specific changes in the size of flooding events in rivers and streams.

And regarding sea level rises, Koonin points out:

even if we were the culprit and ceased all emissions tomorrow, global sea level would continue to rise. What’s more, as we’ve seen, local sea level changes and their effects are far more complicated still, involving ocean currents, erosion, weather patterns, and land use and composition. Clear and unbiased communication of these nuances is essential.

Michael Shellenberger, in his book “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All,” writes, “In fact, both rich and poor societies have become far less vulnerable to extreme weather events in recent decades. In 2019, the journal Global Environmental Change published a major study that found death rates and economic damage dropped by 80 to 90 percent during the last four decades, from the 1980s to the present.”

But today, media sources seem devoid of essential nuance. As Koonin explains:

as the age of the internet advanced, headlines became more provocative to encourage clicks—even when the article itself didn’t support the provocation. Today, the shift toward the alarming—and shareable—has traveled well beyond the headlines. That’s especially true in climate and energy matters. Whatever its noble intentions, news is ultimately a business, one that in this digital era increasingly depends upon eyeballs in the form of clicks and shares. Reporting on the scientific reality that there’s been hardly any long-term change in extreme weather doesn’t fit the ethos of If it bleeds it leads. On the other hand, there is always an extreme weather story somewhere in the world to support a sensational headline … “[C]limate reporters’” … mission is largely predetermined; if they don’t have a narrative of doom to report, they won’t get into the paper (whether digital or print) or on the air … Carl Wunsch, a prominent oceanographer from MIT who has long urged scientists to be realistic in their portrayal of the science, has written about the pressures on climate scientists to produce splashy results: “The central problem of climate science is to ask what you do and say when your data are, by almost any standard, inadequate? If I spend three years analyzing my data, and the only defensible inference is that ‘the data are inadequate to answer the question,’ how do you publish? How do you get your grant renewed? A common answer is to distort the calculation of the uncertainty, or ignore it all together, and proclaim an exciting story that the New York Times will pick up.”

(Some more interesting comments on the financial incentives of scientists to promote more extreme climate change predictions can be found between the 42:59 and 44:15 minute marks in this video here.)

As Koonin says in a January, 2025 interview:

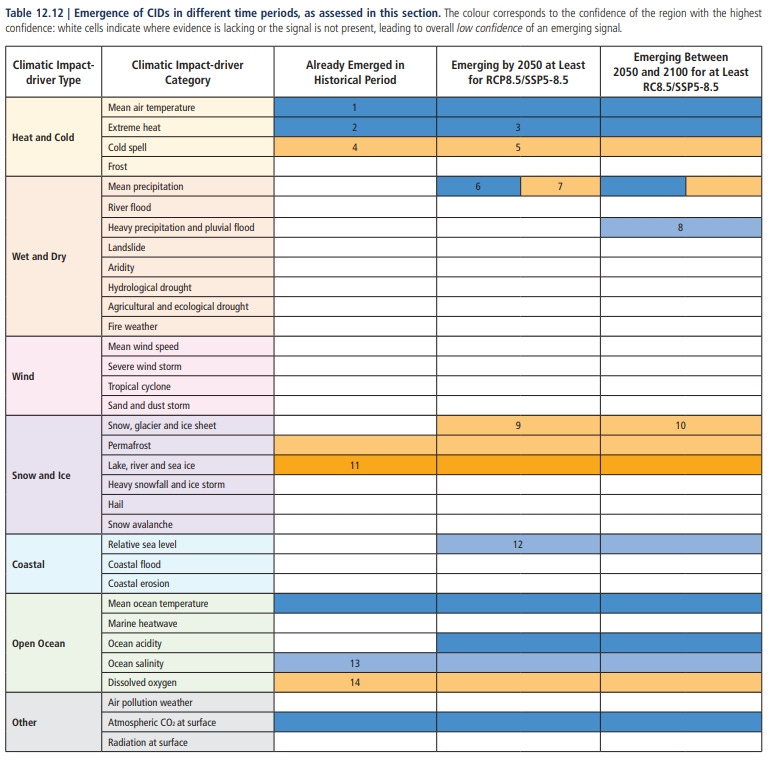

[T]he Working Group 1 of the most recent report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was issued in 2021. They have a wonderful table, Table 12.12, that shows 33 different kinds of what they call climate “impact-drivers”: floods, hurricanes, heat waves, cold, drought, etc. And for the great majority of those drivers, the table is blank. Meaning they couldn’t find any long-term trend, let alone one that could be attributed to human influences. This makes it hard to understand how people, including the UN secretary-general, keep saying the climate is broken.

Koonin gives some advice on what non-scientist readers can look for in articles about climate change to avoid being misled:

Omitting numbers is also a red flag. Hearing that “sea level is rising” sounds alarming, but much less so when you’re told it’s been going up at less than 30 cm (one foot) per century for the past 150 years. When numbers are included, omission of uncertainty estimates is another thing to watch out for in non-expert discussions of climate science … Yet another common tactic is quoting alarming quantities without context. A headline that reads “Oceans are warming at the same rate as if five Hiroshima bombs were dropped in every second” does indeed sound scary, particularly as it invokes nuclear weapons. But if you read further into that article, you learn that ocean temperatures are rising at only 0.04ºC (0.07ºF) per decade. And a basic science refresher would tell you that the earth absorbs sunlight (and radiates an equal amount of heat energy) equivalent to two thousand Hiroshima bombs each second. It’s pretty easy to scare people in the service of persuasion if you don’t give any numerical context.

As daunting as trying to understand the nuances of climate prediction might be for non-scientists, Koonin usefully reminds us all that alleged experts on climate science cannot themselves be experts in the huge variety of fields climate science encompasses. As Koonin writes:

In truth, climate science involves many different scientific fields, encompassing the quantum physics of molecules and the classical physics of moving air, water, and ice; the chemical processes in the atmosphere and ocean; the geology of the solid earth; and the biology of ecosystems. It also includes the technologies used to “do” the science, including computer modeling on the world’s fastest machines, remote sensing from satellites, paleoclimate analysis, and advanced statistical methods. Then there are the related areas of policy, economics, and the energy technologies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This enormous swath of knowledge and methods makes the study of climate and energy the ultimate multidisciplinary activity. No single researcher can be an expert in more than two or three of its aspects, so the challenge in assessing and communicating the state of the science is to read widely and critically enough to put together—and convey, which requires a skill set all its own—a coherent, fact-based picture of the whole.

This makes it particularly hopeless that journalists with dramatic narratives to push will reasonably report on the nuances of climate change:

Many people reporting on climate don’t have a background in science. This is a particular problem because, as we’ve seen, the assessment reports themselves can be misleading, especially to non-experts. Science stories are almost always stories of nuance; they require time and research. Unfortunately, the pace of the news cycle has only become more frantic, and reporters and editors have less time than ever.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll move beyond uncertain predictions of apocalypse to solid bases for optimism in the data showing how, today, we’re getting more out of fewer resources than ever before.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9.