Uncertain Climate Predictions and Certain Energy Progress – Part 9

The bright side of warming and the downside of over-reacting to false claims of climate apocalypse.

In previous essays, we examined the inherent uncertainty of computer model predictions of future climate change, in particular global warming. Yet the Earth is warming, to a modest degree. Should that concern us, regardless of the size of the role human activity has in that warming?

No. Indeed, there’s a bright side to warming.

In his book Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, Steven Koonin writes that “growing seasons have been lengthening slightly” under global warming, and that:

In fact, many analyses suggest that a warming of less than 2ºC is likely to have a small net positive economic impact, thanks to improved agricultural conditions and reduced heating costs in the temperate northern latitudes … [W]arming of 2 to 5°C (3.6-9°F) is projected to have little net economic impact over time.

As the Wall Street Journal notes, extreme cold kills many more people each year (1.3 million) than extreme heat (356,000), according to a study published in the Lancet in August, 2021. Other researchers found the following in 2022:

We examine the impact of temperature on mortality in Mexico using daily data over the period 1998–2017 and find that 3.8 percent of deaths in Mexico are caused by suboptimal temperature (26,000 every year). However, 92 percent of weather-related deaths are induced by cold (<12 degrees C) or mildly cold (12–20 degrees C) days and only 2 percent by outstandingly hot days (>32 degrees C). Furthermore, temperatures are twice as likely to kill people in the bottom half of the income distribution.

Poverty kills far more people each year than anything else. About 10% of the world’s population currently doesn’t even have electricity, and a third still cook with stoves that use wood, coal, crop waste or dung, which kill millions each year.

As Bjorn Lomborg writes:

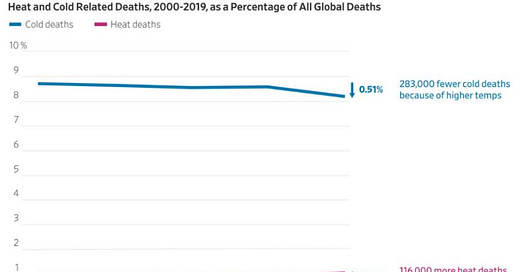

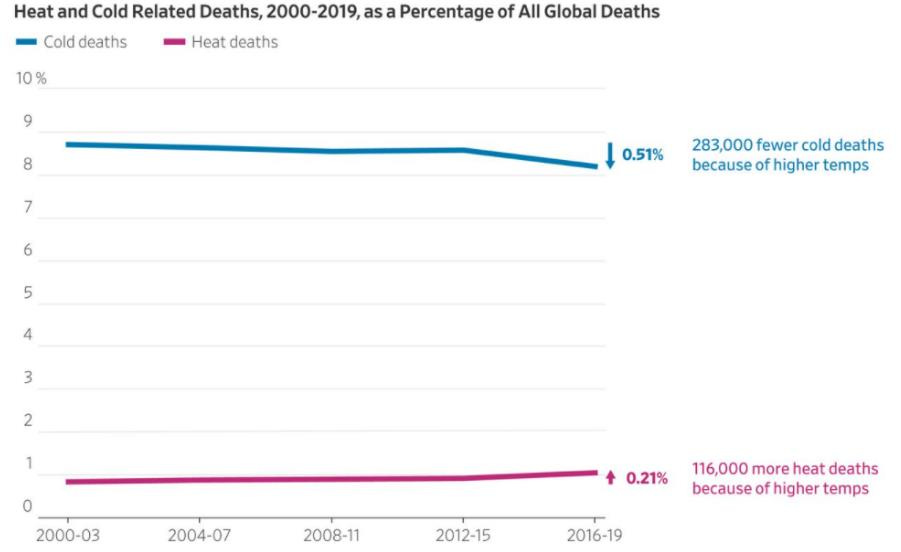

Global warming does cause more heat deaths, but the [leading medical journal] editors’ statistic is deceptive. They say global heat deaths have gone up by 54% among old people in the past 20 years, but they fail to mention that the number of old people has risen by almost as much. Demographics drove most of the rise, not climate change. They also leave out that climate change has saved more lives from temperature-related deaths than it has taken. Heat deaths make up about 1% of global fatalities a year—almost 600,000 deaths—but cold kills eight times as many people, totaling 4.5 million deaths annually. As temperatures have risen since 2000, heat deaths have increased 0.21%, while cold deaths have dropped 0.51%. Today about 116,000 more people die from heat each year, but 283,000 fewer die from cold. Global warming now prevents more than 166,000 temperature-related fatalities annually … Cold is much harder to deal with. Heating a home well all through the winter can be prohibitively expensive for poorer households, even in developed nations. Fracking drove down American natural gas prices. One study estimates that the resulting cheaper heat saved more than 11,000 lives annually by 2010.

Michael Shellenberger, in his book “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All,” reminds us that:

When it comes to food production, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concludes that crop yields will increase significantly, under a wide range of climate change scenarios. Humans today produce enough food for ten billion people, a 25 percent surplus, and experts believe we will produce even more despite climate change. Food production, the FAO finds, will depend more on access to tractors, irrigation, and fertilizer than on climate change, just as it did in the last century. The FAO projects that even farmers in the poorest regions today, like sub-Saharan Africa, may see 40 percent crop yield increases from technological improvements alone … In fact, scientists … at the Potsdam Institute … found that food production could increase even at four to five degrees Celsius warming above preindustrial levels. And, again, technical improvements, such as fertilizer, irrigation, and mechanization, mattered more than climate change. The report also found, intriguingly, that climate change policies were more likely to hurt food production and worsen rural poverty than climate change itself. The “climate policies” the authors refer to are ones that would make energy more expensive and result in more bioenergy use (the burning of biofuels and biomass), which in turn would increase land scarcity and drive up food costs.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change also concludes that “This occurs because . . . land-based mitigation leads to less land availability for food production, potentially lower food supply, and therefore food price increases.”

Shellenberger continues:

Scientists find that higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere available for photosynthesis will likely offset declines in the productivity of photosynthesis from higher temperatures. A major study of fifty-five temperate forests found higher growth than expected, due to higher temperatures resulting in a longer growing season, higher carbon dioxide, and other factors. And faster growth means there will be a slower accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Regarding deaths due to extreme weather generally, as Roger Pielke, Jr. reports:

Over the weekend, I was reading the Aon Global Catastrophe Recap, First Half ((1H) of 2025. In terms of economic losses, the first half of the year was overwhelmingly dominated by losses in the United States (especially the California fires) accounting for more than 90% of total insured losses (~$100 billion). What really jumped out to me was this conclusion: “At least 7,700 people were killed due to natural disasters during the first half of 2025, which is well below the 21st-century average of 37,250. Majority of the deaths (5,456) occurred as a result of the earthquake in Myanmar.” That means that ~2,200 people worldwide died in catastrophes related to extreme weather events during the first six months of the year. On the one hand, ~2,200 deaths are a lot and every loss of life is tragic. On the other hand, in the context of historical losses related to weather extreme, on a planet of 8.2 billion people, ~2,200 deaths is incredibly low. Historically low, in fact. It is likely that the first half of 2025 has seen the fewest deaths related to extreme weather of any half year in recorded human history.

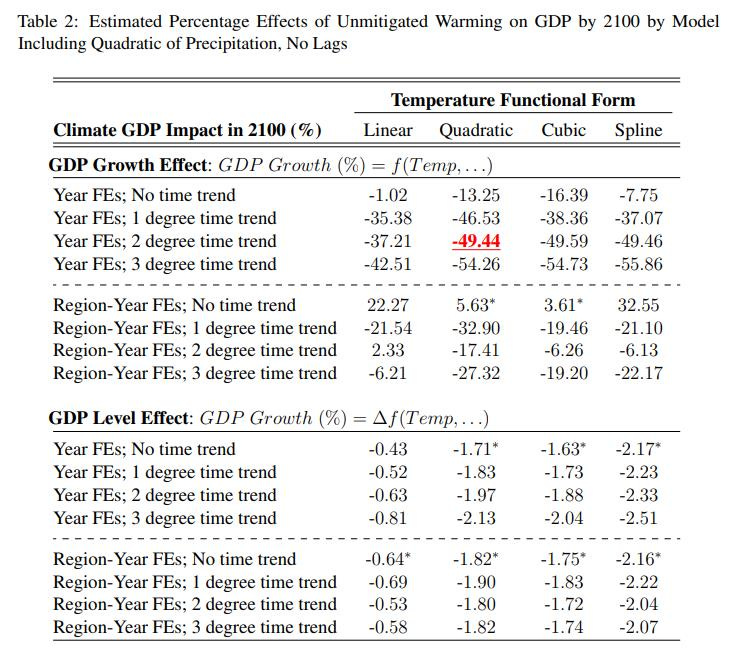

And beyond failing to appreciate the upside of warming, there’s a huge downside in responding to inaccurate predictions of increased warming by imposing severe limits on economic growth. A review of studies on the effects of climate change show that if we were to follow even well-intentioned policies of keeping temperature increases below 2.5 degrees Celsius by targeting zero emissions by 2040, as many climate activists advocate, we would actually end up worse off, because we would be sacrificing current economic growth at rates in excess of what we could expect to gain in the future from implementing those policies. That is, one wouldn’t want to spend 2% of current GDP to save 2.1% of GDP due to climate change in 80 years, because 1% of world GDP is $800 billion. A reduction in world GDP by that amount over a century comes to $80 trillion. With modest growth of around 2% it comes to around $300 trillion over a century. So while it may be worthwhile to spend 0.1% of GDP to protect 2% of GDP growth in 80 years, it would not have made sense, for example, for the world to have given up the Industrial Revolution 150 years ago just to make the climate today 0.1 degrees Celsius cooler. The authors of the study conclude:

Accounting for the uncertainty reflected in the set of superior models, we do not identify a statistically significant marginal effect of temperature on global GDP growth. Though we cannot preclude at 95% confidence that a model relating temperature to GDP growth is superior, we identify models relating temperature to GDP levels as more often being the most accurate in out-of-sample validation. Models relating temperature to GDP levels yield climate impact estimates that are far more certain. The best such models imply GDP losses by 2100 of 1-3%, consistent with damage functions currently embedded in the major integrated assessment models that underpin the U.S. social cost of carbon. The 95% confidence range for GDP levels models in any model confidence set is -8.5% to +1.8%. Hot temperatures are estimated to cause statistically significant losses to the level of poor country and agricultural GDP, but not to rich-country and non-agricultural production. While the climate change impacts estimated by GDP-levels models may appear modest, even a 1% loss to global GDP is equal to $800 billion today and could be 5-12 times greater by 2100 amid 2-3% annual economic growth. Moreover, projected GDP impacts based on past temperature fluctuations reflect only a component of potential welfare effects, excluding, for instance, effects on non-market goods like environmental amenities and potential extreme events not reflected in the historical record.

And as Benjamin Zycher at the American Enterprise Institute writes, “increased GHG [greenhouse gas] concentrations yield benefits as well. Among those are planetary greening, increased agricultural productivity, a substantial reduction in net mortality from cold and heat, and increased water use efficiency by plants.”

That concludes this series of essays on uncertain climate predictions and certain energy progress.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9.