Uncertain Climate Predictions and Certain Energy Progress – Part 6

Who would certainly be hurt if we ignored the uncertainties behind climate claims and imposed significant restrictions on energy use?

In previous essays we explored the significant uncertainties surrounding computer climate change model predictions. In this essay, we’ll explore who would be hurt, and how, if we just (however incorrectly) assumed those climate models were correct and imposed restrictions on energy use accordingly.

In his book Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, Steven Koonin writes:

According to the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change], just stabilizing human influences on the climate would require global annual per capita emissions of CO2 to fall to less than one ton by 2075, a level comparable to today’s emissions from such countries as Haiti, Yemen, and Malawi. For comparison, 2015 annual per capita emissions from the United States, Europe, and China were, respectively, about 17, 7, and 6 tons.

So any energy reductions of that magnitude would disproportionately hurt developing economies. As Koonin continues:

Energy demand increases strongly and universally with rising economic activity and quality of life; global demand is expected to grow by about 50 percent through midcentury as most of the world’s people improve their lot.

We in America already have ready access to energy, but many others around the world don’t:

And where your interests come out … will depend on the country you’re in, how wealthy you are, and how much you care about (or whether you’re a member of) the forty percent of humanity that doesn’t have access to adequate energy … [T]he world will need much more energy in the coming decades, in part because of demographics. Today’s global population of just under eight billion will grow to over nine billion by midcentury, with virtually all of that growth occurring outside the developed world. That last detail is important, because the economic betterment of most of humanity in the coming decades will drive energy demand even more strongly than population growth … People in every developing country (including China, India, Mexico, and Brazil) consume more energy as their economies grow—they build infrastructure, ramp up industrial activities, demand more food, electricity, transportation, and so on. People in developed countries show a high but slow-growing energy demand, with differences among them depending upon the nature of their economic activity, their infrastructure, and their climate (because of heating and cooling needs) … [W]hile US emissions declined in the period after 2005, global emissions still increased by about one-third [worldwide].

As Bjorn Lomborg writes in the Wall Street Journal:

A rapid global transition from fossil fuels is, and always has been, impossible. There are several reasons that make it so. Many developing nations never shared the Western elite’s obsession with reducing emissions. Life for most people on earth is still a battle against poverty, hunger and disease. Corruption, lack of jobs and poor education hamper their futures. Tackling global temperatures a century out has never ranked high among the priorities of developing countries’ voters—and without their cooperation, the project is doomed. Geopolitical changes since the 1990s have also limited climate ambitions. Russia, Iran and North Korea have emerged as a destructive and destabilizing axis opposed to global security. Despite their occasional claims to the contrary, none of these nations will support global climate-change-mitigation efforts. According to a McKinsey report, achieving the vaunted net-zero emissions target by 2050 would require Russia to adopt policies that cost more than a quarter of a trillion dollars a year—around three times as much as Moscow spent on its military last year. Don’t hold your breath. Beijing talks a good game about climate change, but China’s economic growth has relied on burning ever more coal. China is the world’s pre-eminent greenhouse-gas emitter and produced the largest increase of any nation last year. Renewables made up 40% of China’s primary energy in 1971. By 2011 they had fallen to about 7%, as coal use increased. Renewables have since inched up to 10%. Strong climate action could cost China nearly a trillion dollars annually. No wonder Beijing is dragging its feet. This dynamic means that most of the world, particularly India and much of Africa, will continue to focus on becoming richer through fossil fuels. Russia and its allies will ignore the West’s fixation on climate change. China will simply make money from selling the West solar panels and electric cars while only modestly curbing its emissions.

As Koonin asks “Who will pay the developing world not to emit?” After all, “most of the world’s people need more energy to have even the minimal quality of life we take for granted in the developed world.” As Koonin reminds us, “you may be surprised to hear that the amount of energy provided by wood (by far the leading energy source for most of the nineteenth century) is today the same as it was at the time of the Civil War, though other sources of energy have grown enormously since then.”

Robert Bryce describes the importance of electricity to the developing world in his book “A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations.” He explains his thesis as follows:

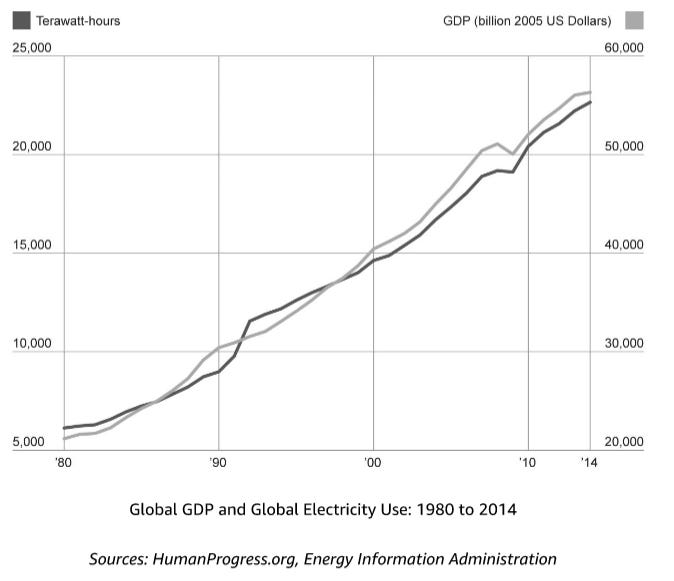

The numbers of the disempowered are staggering: About one billion people on the planet today have no access to electricity at all. Another two billion or so are using only tiny amounts … That leads to the thesis of this book: electricity is the fuel of the twenty-first century. Electricity makes modern life possible. And yet, some three billion people around the world are still stuck in the dark. Their opportunities, their potential to develop lives beyond the backbreaking work of subsistence farming and day labor, their possibilities for economic and social development, depend on increasing their access to reliable electricity. Electricity is the ultimate poverty killer. No matter where you look in the world, as electricity use has increased, so have personal incomes. Having electricity doesn’t guarantee wealth. But its absence almost always means poverty. How we empower the powerless while meeting soaring global electricity demand will be the key factor in addressing some of the world’s biggest challenges, including women’s rights, climate change, and inequality … The correlation between electricity use and economic growth can be seen in the chart here, which shows that the two move in near unison and they’ve been dancing cheek-to-cheek for decades.

Access to electricity right now is essential to the liberation of women around the world. As Bryce writes:

Electricity emancipates women and girls from the pump, the stove, and the washtub. And the largest number of women and girls around the world who need to be rescued from electricity poverty are people like Rehena Jamadar. They live in places like Majlishpukur— small, rural, predominantly Muslim villages far from urban centers. Over the next few decades, bringing abundant, reliable electricity to women like Rehena will be key to global poverty-eradication efforts. Those electrification efforts will be particularly challenging in Islamic countries. Why? Over the next few decades the world’s Muslim population is expected to surge. By 2060, according to projections from the Pew Research Center, the world’s Islamic population will grow by more than 1.2 billion people, and will be as large as the world’s Christian population. Hundreds of millions of those new Muslims will be born in places like Majlishpukur, rural agricultural villages where people scrape by on subsistence farming and day labor. The Islamic population will surge because of simple demographics. There are more young Muslims than there are young Christians and those young Muslims are having more babies than their Christian counterparts. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, the median age for Muslims is seventeen. In North America, the median age for Christians is forty. The Pew report estimates that by 2060, 27 percent of the world’s Muslim population will be living in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2015, that figure was 16 percent. Another Pew study, this one published in 2016, about the education gap among the various religions, provides yet more reason to be concerned. The 2016 study found that Muslims, on average, have just 5.6 years of formal schooling. By contrast, Christians obtain an average of 9.3 years of formal schooling and Jews get 13.4 years (the most of any religion). The disparity is particularly obvious among women. Muslim women trail men in formal schooling by 1.5 years. That is, the average male Muslim gets 6.4 years of formal schooling while the average female Muslim gets just 4.9 years. Thus, the future of the Christian and Muslim worlds appears to be one where there will be an ever-widening gap, where Jews and Christians will continue to be electrified— and therefore educated— but hundreds of millions of Muslims will be undereducated, impoverished, and living without electricity.

Electricity’s power to liberate women extends far beyond the Middle East. As Bryce writes:

Of course, electricity matters to all women, not just Muslim women. According to estimates by Hans Rosling, the late Swedish academic and statistician, about five billion people on the planet are walking around today wearing clothes that have been washed by hand. That means that roughly 2.5 billion women and girls— as part of their daily, or weekly, routine— are washing those clothes. By hand. In buckets or washtubs. And every hour that women and girls spend at the washtub is one missed in the classroom, bookstore, or library. The women and girls who live in electricity poverty have never gotten used to the convenience of a washing machine or refrigerator, to say nothing of a Cuisinart or Instant Pot … Numerous academic studies have shown the positive effect electrification has on women and girls. A 2002 study in Bangladesh by Abul Barkat, an economist at the University of Dhaka, found that the literacy rate for females in villages with electricity was 31 percent higher than it was in villages that lacked electricity. The study concluded that the availability of electricity has a “significant influence on education, especially on the quality of education. This influence is much more pronounced among the poor and girls in the electrified households than the poor and girls in non- electrified households.” A 2010 study on post-apartheid electrification in South Africa found that “employment grows in places that get new access to electricity.” This was particularly true for women. The study found that electrification led to “large increases in the use of electric lighting and cooking, and reductions in wood-fueled cooking over a five-year period, as well as a 9.5 percentage point increase in female employment.” A 2012 study of rural electrification in India concluded that the availability of electricity had a significant impact on schooling for girls, finding that electrification access increases school enrollment by about 6 percent for boys and 7.4 percent for girls. It also increases weekly study time by more than an hour, and the increase is slightly more for girls than boys. As a result of more study hours, children from households with electricity can be expected to perform better than their peers living in households without electricity. The same study found that “the impact of electrification on labor supply is positive for both men and women; that is, household access to electricity increases employment hours by more than 17 percent for women and only 1.5 percent for men.” Further, the study found that electrification reduces the poverty rate by 13.3 percent, and it concluded that “these findings indicate electrification’s substantial positive effect on overall household welfare.” … Whether the issue is voting rights, education, or work opportunities, the facts show that electricity helps women and girls. After we visited Majlishpukur, I did a formal interview with Joyashree Roy. I asked her how policymakers should think about electrification in poverty-stricken places like India, particularly given electricity’s importance to women and its role in climate change. She said, “You cannot deny them this access to modernity.” She argued that for “the rest of the world, who is enjoying modernity, and we are not allowing others to be modern, is a crime. It is a major crime.” Electricity, she said, is essential to women. “If your mother is educated then she understands the beauty of knowledge,” Joyashree told me. If women don’t have electricity, and therefore miss their opportunity to be educated, then, “we are missing two generations, mother and the girls.”

It's striking how many people on Earth are denied the benefits of electricity:

Roughly 3.3 billion people— about 45 percent of all the people on the planet— live in places where per- capita electricity consumption is less than 1,000 kilowatt-hours per year, or less than the amount used by my refrigerator. According to the International Energy Agency, of those 3.3 billion Unplugged people, about one billion have no access to electricity at all … The countries in the Unplugged segment include places like El Salvador, the Philippines, Bolivia, Pakistan, and India. On nearly every metric of human well-being, whether it’s child mortality or life expectancy, the residents of the Unplugged countries trail far behind the people living in Low-Watt and High-Watt places. For instance, people living in High-Watt countries live, on average, about sixteen years longer than those in Unplugged countries. The child mortality rate in Unplugged countries is nearly ten times higher than the rate in High-Watt places. The average per-capita GDP in Unplugged countries is about $1,973 per year, or about twenty times smaller than in High-Watt countries, where the average is about $38,844.

And coal remains the cheapest way for those in Unplugged countries to get electricity:

First and foremost, [coal is] cheap. For Asian countries, coal is about one-half to one-third of the price (on an energy-equivalent basis) of imported liquefied natural gas. Second, coal prices are not affected by any OPEC-like entities. That means no single country, or group of countries, can reduce supply and therefore cause price spikes. Third, coal deposits are widely dispersed geographically. Fourth, the world has gargantuan coal deposits. At current rates of consumption, global coal reserves are projected to last another 134 years. The United States and Australia both have more than three hundred years’ worth of coal reserves in the ground. Russia has nearly four hundred years’ worth. The large number of countries that produce and export coal allows buyers to compare prices from a number of suppliers and therefore get the best quality and price.

Bryce describes how the demand for electricity can only escalate:

In 2018, global electricity use jumped by 4 percent. At that rate of growth, global electricity use will double in just eighteen years. That means that the amount of installed electricity generation capacity around the world will increase from roughly 6 terawatts today to about 12 terawatts by the late 2030s … [W]ithin three decades or so, global electricity demand solely for air conditioning will be nearly equal to the total amount of electricity now used by China … In summary, there’s no doubt that we will need vastly more electricity in the decades to come than we have now. Adding 6 terawatts of new generation capacity will be a huge challenge. To put that in perspective, recall that the United States currently has about 1 terawatt of generation capacity. Therefore, over the next three decades or so, the countries of the world will have to add six grids the size of the existing US grid.

Can renewable sources of energy, such as wind and solar power, hope to provide this inevitable demand for more energy by people struggling to enjoy anything close to our standard of living? That will be the subject of the next essay in this series.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9.