In this continuing series on teachers unions and their influence on American public education, this essay focuses on how teachers unions have increasingly moved away from treating teachers as professionals and toward treating them as political activists.

As Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

Among supporters, a common refrain is that the unions are the vanguard of professionalism in public education. The notion here is that unions try to secure better salaries and working conditions for teachers, expand teacher rights and autonomy in the workplace, and push for higher levels of teacher training— all of which are hallmarks of professionalism. In so doing, supporters argue, they help to make teaching a more desirable job, attract higher-quality people, increase the quality of those already in the field, and ultimately boost the productivity of the schools. The reality is that the teachers unions do not promote professionalism in public education. They do the opposite— ensuring that, in the formal structure of schooling, teachers are treated like blue-collar workers, and that the value of their professionalism cannot be fully realized. Yes, the unions do try to raise teacher salaries, but that is hardly germane. Accountants are paid far less than brain surgeons, but both are professionals, and their relative salaries have nothing to do with how professional they are. More important is how the unions approach the whole subject of salary setting. Their ideal is the single salary schedule, in which every teacher's salary is strictly determined by seniority and credentials — and thus is entirely rule-governed and has zero to do with their performance. They also try to see to it that teachers are paid for every minute that they work. They want rules that specify exactly how many minutes teachers need to be in the classroom, how many minutes of preparation time they are guaranteed, and how much time they need to stay on campus. And they seek rules that minimize all work activities outside the classroom (meetings with parents, faculty meetings, after-school meetings with kids) for which teachers are not explicitly paid extra. This is an industrial approach characteristic of what blue-collar unions insist upon for unskilled workers. It bears no resemblance to the way doctors, lawyers, business managers, and other professionals are paid, as their compensation typically does depend on their performance (and the satisfaction of their clients), and they work as long as they need to work in order to do their jobs well … [The union approach] discourages high-quality people from entering teaching (and staying), because these people know that, unlike in a truly professional setting, their talent and success will not be rewarded … [T]he teachers unions have approached training in the same way they approach everything else: in terms of their self-interest. They support the ed schools not because the training provided there is any good, but because the ed schools are their close friends and allies, because the existing system of laborious, time-consuming, formal certification and ed school training has all the symbolic trappings of professionalism (making education look like law and medicine) …

Most of us a familiar with the tedious nature of many “professional development” seminars, but teachers unions turn tedium into take-home pay. As Moe writes:

When it comes to on-the-job training for veteran teachers -- often referred to as professional development -- the unions are again big supporters. The idea sounds good: teachers engage in continual training throughout their careers to maintain and enhance their classroom skills. But the fact is, the unions do not have a stake in high-quality training that really pays off in student performance. Thanks to the single salary schedule, they have a stake instead in supporting various types of professional development programs—however shoddy and irrelevant they may be -- that teachers can use to get formal credits that qualify them for higher levels of pay, whether or not they become better classroom teachers. Not surprisingly, there is little evidence that most of what passes for professional development is effective … The traditional, education school approach to teacher certification, which the states have long relied upon to ensure teacher quality, has never been shown to promote student learning. It is costly, time-consuming, and adds little value. Because this is so, alternative approaches to certification have the potential to be transformative in boosting teacher quality. Properly designed, they could sweep away these needless barriers to entry, allow competent people to get certified quickly at little cost, and vastly increase the pool of candidates that districts have to choose from. Most alternative certification programs in the American states, however, are not intended to do these things. Yes, they help districts out by allowing them to hire people who initially lack formal certification. This expands their choices somewhat, which is good. But the people they hire are then typically required to get certified over time by fulfilling a vast array of traditional requirements, often by earning course credits comparable to those of a master's degree -- and often by attending education schools. Thus, most of the old costs and hurdles are still there, dissuading potential candidates from entering the field, especially those who are high in quality and likely to have attractive opportunities in other lines of work. While putting up with weak alternative certification programs, then, the unions have remained staunch defenders of the teacher training status quo and all its unnecessary hurdles and obstacles. As NEA President (at the time) Reg Weaver put it a few years ago, “The solution is not to develop alternative routes of entry into the profession or to increase the supply of recruits by allowing prospective teachers to skip ‘burdensome' education courses or student teaching. The solution is to show a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T, and show us the money.”

As Frederick Hess writes:

[W]hy are schools riven by bitter fights over whether educators should teach that America is a “white supremacist” nation or talk to first-graders about gender identity? Who is responsible for pushing this toxic tripe? It’s mostly a mistake to blame the nation’s teachers and school leaders. In three decades of working with educators and writing about education, I’ve known precious few kindergarten teachers eager to talk about gender or make kids fill out “privilege worksheets.” Education Week reports that 56 percent of educators oppose teaching their students “about the idea of critical race theory” and that just 29 percent self-identify as liberal (5 percent as “very liberal”). Instead, the lion’s share of the blame should be reserved for the farrago of education-school faculty, diversity consultants, foundation-financed frauds, and bureaucrats who train our nation’s teachers. Unable or unwilling to improve the quality of teaching, too many of these unaccountable charlatans have instead taken to promoting personal agendas, pushing outrageous practices, and browbeating school staff into parroting radical doctrines. Teacher training is a big industry. The federal government provides states and districts more than $2 billion a year for teacher training, but the total far exceeds this figure. The largest 50 districts alone spend an estimated $8 billion annually on teacher professional development (PD), and their teachers spend about 10 percent of their work year (nearly four weeks) in training sessions. Back in 2014, the Boston Consulting Group estimated that total spending on teacher PD in the U.S. topped $18 billion annually. Unlike teachers and school leaders, who actually live in their communities, know their students, and interact with parents, these consultants tend to drop by, do their dance, and then scoot out of town with a bag full of cash. While these trainers have long operated without much scrutiny or vetting, the CRT [Critical Race Theory] debate has prompted a wave of Freedom of Information Act requests that raise red flags. Last July, the Loudoun County Public Schools in Virginia hired trainers from the “Equity Collaborative” to teach educators that they mustn’t “profess color blindness” but instead need to accept that “addressing one’s Whiteness (i.e., white privilege) is crucial for effective teaching.” Teachers were taught that “fostering independence,” “individual achievement,” “individual thinking,” and “self-expression” are racist hallmarks of “white individualism.” Trainers in Seattle Public Schools taught teachers that the U.S. is a “race-based white-supremacist society,” that our education system commits “spirit murder” against black children, and that white teachers must “bankrupt [their] privilege in acknowledgment of [their] thieved inheritance.” In San Diego, trainers have taught educators that “Whiteness reproduces poverty, failing schools, high unemployment, school closings, and trauma for people of color.” In Buffalo, N.Y., trainers designed a curriculum requiring schools to embrace “Black Lives Matter principles.” Teachers were told they should promote “queer-affirming network[s] where heteronormative thinking no longer exists” and seek “the disruption of Western nuclear family dynamics.” Kindergarten teachers were directed to discuss “racist police and state-sanctioned violence,” and fifth-grade teachers to teach that a “school-to-grave pipeline” exists for black children. Trainers in Davis, Calif., taught teachers how to “decolonize their language and deconstruct that which they’ve been taught about gender.” The Eau Claire Area School District in Wisconsin held training in February 2022 for educators on gender identity. The trainers told teachers to find ways to “strategize the support of your LGBTQ+ students, without the support of their parents.” Teachers were taught that “parents are not entitled to know their kids’ identities.” In the Los Angeles Unified School District, teachers were instructed that “all students have the right to be referred to by their chosen names/pronouns, regardless of their legal or school records,” that refusing to “respect a student’s gender identity” violates district policy, and that “no parent/guardian permission or notification is required for student-initiated name changes” (boldface and italics in original). Offering these sessions is often a lucrative side hustle for trainers who otherwise work as academics and writers. Robin DiAngelo, the author of White Fragility, charges an average fee of $14,000 per event and collects an estimated $700,000 a year in speaking fees. Lesser-known Seconde Nimenya charges $10,000 to $20,000 a gig for her diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training. Her clients include a raft of schools and colleges and the Association of California School Administrators. Anti-racist firebrand Ibram X. Kendi was paid $20,000 by Virginia’s Fairfax County Public Schools to give a 45-minute virtual presentation and participate in a 15-minute Q&A as part of “Racial Truth and Reconciliation Week”; the district spent another $24,000 to buy his books. Shawn Andrews, self-billed as a “Diversity & Inclusion Keynote Speaker,” charges $15,000–$20,000 for in-person events. But that would be pocket change for Kimberlé Crenshaw, the foundational CRT guru, who charges $50,000 to $100,000 per speaking engagement. Keep in mind that teachers actually teach kids and talk to the parents of their students. This tends to keep them grounded. These trainers, on the other hand, aren’t expected to linger in classrooms or live with the practical consequences of their diktats. Instead, they’re free to treat students as abstractions and schools as laboratories. And educators, fearful of being labeled bigots or racists, get bullied into mouthing the consultants’ woke pieties … Here’s the thing: There’s hardly any evidence that teacher training improves teaching. A massive 2014 meta-analysis by the federal Institute of Education Sciences, for instance, evaluated 643 studies of professional development in K–12 math instruction. Of those studies, only 32 even examined whether PD caused student improvement, just five of the 32 met the evidentiary bar set by the What Works Clearinghouse, and just two of the five showed positive effects due to PD. Linda Darling-Hammond, former president of the American Education Research Association, has acknowledged that the training educators receive is “episodic, myopic, and often meaningless.” As the Brookings Institution’s Tom Loveless has politely put it, “in a nutshell, the scientific basis for PD is extremely weak.” In his own research review, he summed things up thus: “When I hear people say that we know what good PD is, or that we know how to improve teaching but lack the will to do so, my initial reaction is that people who say such things are engaged in wishful thinking … ” The billions of dollars that districts currently allocate for teacher trainers could be put to better use. It could provide pay bumps for educators who do exceptional work, teach hard-to-staff subjects, or it could underwrite mentorship programs for young colleagues — in the expectation that more sustained, serious support might help reduce high rates of attrition among new teachers. Eliminating these training sessions would free up valuable teacher time. When teachers were asked this spring in the Merrimack Teacher Survey which tasks they would like to spend less time on, professional development was one of the most popular responses. Indeed, several years ago, the New Teacher Project surveyed “successful” teachers and reported that they found PD sessions far less useful than additional practice, observing colleagues at work, or receiving feedback from mentors.

A side note regarding Ibram X. Kendi, whose book How to Be An Antiracist is prominently recommended by those who run teachers training outfits. As Hess also notes, Kendi is prone to phenomenally huge factual errors:

Perhaps the nation’s most prominent “anti-racist” scholar is Ibram X. Kendi, the MacArthur Genius award winner and bestselling author of How to Be an Anti-Racist. In his September 2020 cover story for The Atlantic, he wrote, “The motto of the United States is E pluribus unum—‘Out of many, one.’ The ‘one’ is the president.” It’s kind of remarkable: This staggeringly influential historian managed to get two historical facts wrong in the space of 19 words. The national motto has in fact been “In God we trust” since 1956. More notably, the “one” of “E pluribus unum” is not the president but the union of 13 colonies.

In contrast to teachers unions, there is an organization that is widely viewed as promoting authentic professionalism: it’s called Teach for America. As Moe writes:

Perhaps the most exciting development in the realm of alternative certification is not a governmental reform at all. It is the rise of Teach for America (TFA), a privately funded organization that, beginning in 1990 and growing like gangbusters ever since, has recruited, trained, and placed thousands of the nation's elite college students to teach in the most disadvantaged public schools. For the 2009-10 school year TFA received some 35,000 applications from students at top universities, including—how remarkable is this?—fully 11 percent of all seniors at all Ivy League universities and 35 percent of all African American seniors at Harvard. Anyone interested in resolving the teacher-quality problems of the public schools would have to see TFA as an obvious gold mine of talent. That's exactly what it is. Research has shown, moreover, that despite their lack of experience in the classroom, TFA teachers perform at least as well as their more experienced colleagues, especially in math and science. Yet for the teachers unions, Teach for America is not a gold mine at all. It is a threat, and it has been treated as one -- in part because the success of TFA candidates is graphic evidence that education schools and all the other traditional barriers to entry are simply unnecessary, and in part because these new recruits may essentially be hired in place of more senior teachers in times of layoffs. So rather than welcoming TFA with open arms as a boon to better teaching, the unions have gone on the warpath, pressuring the districts not to hire TFA grads and taking every opportunity to talk it down and undermine its reputation. According to John Wilson, executive director of the NEA, Teach for America hurts children by bringing “the least prepared and the least experienced teachers” into the schools. “What they're doing to poor children,” he says, “is malpractice.” … In 2009-10 only about one-tenth of TFA applicants were placed in teaching jobs. As the Wall Street Journal observes, “Union and bureaucratic opposition is so strong that Teach for America is allotted a mere 3,800 teaching slots nationwide … Districts place a cap on the number of Teach for America teachers they will accept … In Chicago, former home of Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, it is an embarrassing 10 percent. This is a tragic lost opportunity.”

Instead, teachers unions promote paper credentials from colleges of education, most of the faculty of which parrot the union line because a focus on education college credentials, of course, keeps them in business. As Michael Hartney writes in How Policies Make Interest Groups: Governments, Unions, and American Education:

Teachers, unions, and other establishment education interests (e.g., colleges of education) have a vested material interest in the current practice of paying teachers more for earning advanced degrees. Unfortunately, research shows that students do not, as a general rule, benefit from being taught by teachers who have an advanced degree. According to one recent meta-analysis of this scholarly literature, “out of 102 statistical tests examined, approximately 90 percent showed that advanced degrees had either no impact at all or, in some cases, a negative impact on student achievement.” While there are some important exceptions to this general rule, the immense resources that are currently devoted to paying teachers a premium for earning a master’s degree are not creating much of a learning return for students. Were school districts to redirect those current investments away from paying for advanced degrees and toward, say, offering higher starting teacher salaries or paying teachers more to teach in hard-to-staff schools, then student and teacher interests would be working more in concert with one another.

And as teachers unions have veered away from professionalism, they’ve turned toward politics. As Hartney writes, back in the 1950’s teachers avoided politics:

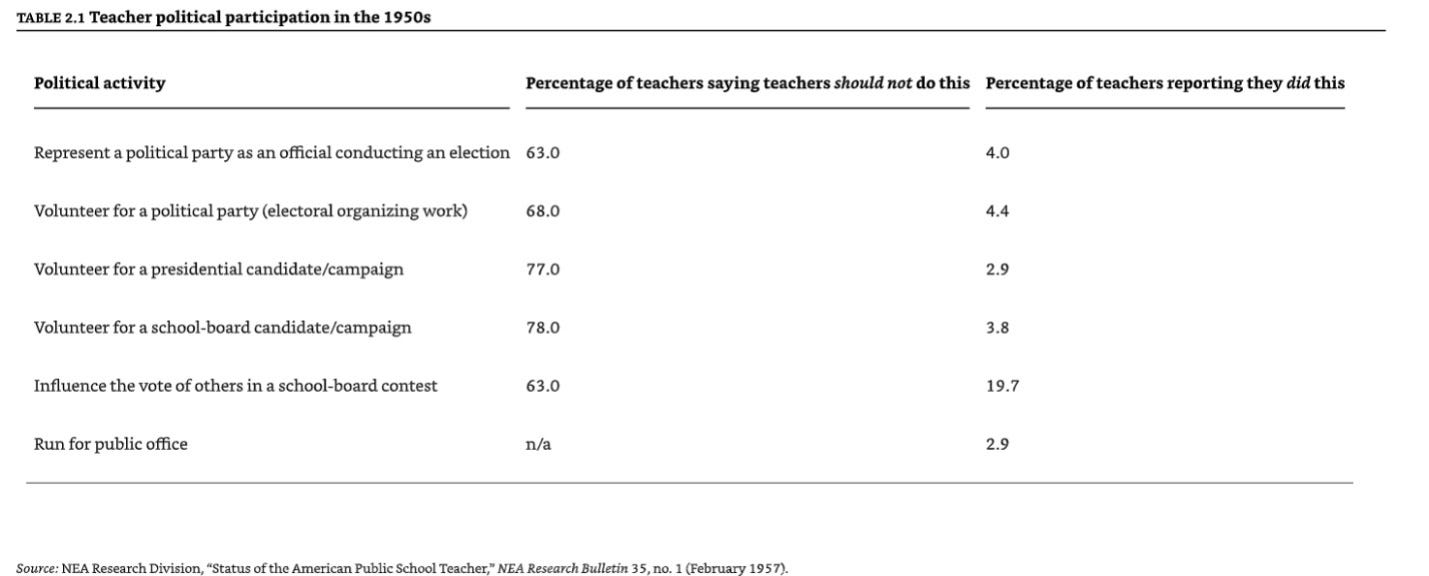

Just how inactive were the nation’s teachers? In 1956, the National Education Association (NEA) surveyed a representative sample of the American teacher workforce and found that two-thirds believed that teachers should not participate in any form of political activity beyond voting. Table 2.1 highlights the full extent of teacher disengagement across a broad range of political activities. Only one out of five educators, for example, said that teachers should volunteer on behalf of a presidential candidate. Two-thirds said that teachers should not volunteer for a political party. Fewer than one in twenty teachers indicated that they had ever done so. Finally, when asked if they had ever run for public office, fewer than 3 percent of teachers said that they had.

… [T]hese earlier patterns of teacher disengagement in local politics are remarkable. Today, teachers are considered the most active group in school-board elections and teachers union–endorsed candidates win the majority of all contested school-board races. By no later than the mid-1970s, members of the nation’s two largest school-employee unions began a longstanding tradition of sending the largest share of delegates to the Democratic Party’s national convention (DNC). In most years, teachers union–affiliated delegates would go on to achieve more representation at the DNC than the entire state of California had.

The teachers union’s embrace of the Democrat party politics is a function of their need for political allies, since they will be working with elected politicians to approve collective bargaining agreements. As Moe writes:

In the legislative policy process, for instance, [teachers unions] enhance their own power -- and attract support for their own educational objectives -- by broadening their network of interest group allies and taking a lead role in the liberal policy coalition. This gets them actively involved -- alongside such groups as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union, the trial lawyers, People for the American Way, and many labor unions -- in supporting the liberal policy agenda more generally. In return, the teachers unions can expect liberal allies to come to their aid in education and help them win. But notice how the formula works: to be winners in education, the unions can't focus just on education. They need to be part of larger coalitions and involved in a broader range of issues. Internally, this is a source of problems. Republican and conservative teachers surely want their unions to be politically successful in advancing their occupational interests. But it is inevitable that, at least for some, the unions' close association with liberal policies and the Democratic Party will be a source of dissatisfaction and even alienation and antagonism. In an important sense, there is nothing the teachers unions can do about this. It is a built-in tension. As human beings, Republican and conservative teachers have values and concerns that go well beyond their narrow occupational interests; and in the grander scheme of life, they may want Republican candidates elected and liberal policies defeated. But the union is not, and cannot be, in the business of representing its members as full-blown human beings. It is in the business of representing their much more narrow interests as employees. And when it does so, some of these human beings are going to feel that their other values and concerns are not being met … If we look just at teachers who are union members, the partisan advantage for Democrats is greatly magnified: Democrats outnumber Republicans by two to one, 51 to 25 percent. The disproportion is greater among women than men, but the men are still overwhelmingly Democrats and just as unlikely to be Republicans as the women are. These union members are entirely responsible for the Democratic tilt within the larger population of teachers. In fact, teachers who do not belong to unions are markedly skewed the other way, with 46 percent saying they are Republicans and 30 percent saying they are Democrats … Among teachers as a whole, the tilt is toward liberalism: 43 percent of teachers rated themselves as liberal and 35 percent as conservative. There are only slight differences, moreover, between men and women. As with partisanship, the liberal tilt of the teacher population is due to the ideological orientations of the teachers who are union members. Within this group, liberals heavily outnumber conservatives by 48 to 31 percent, with men and women looking very much the same. Teachers who are not union members, in contrast, are heavily conservative, by 46 to 30 percent, and this conservative tilt is present among women as well as men (although it is especially marked among the latter) … [A]lmost three-fourths of all nonmembers are located in the sixteen states that don't have collective bargaining laws, and these are the most conservative areas of the country … Finally, there may be another explanation at work here as well. Whatever teachers' political views happen to be when they become members, they may be socialized through their ongoing experiences within the unions -- through newsletters, the appeals of leaders, discussions with colleagues, political campaigns -- to embrace liberal political ideas and the Democratic Party … Among Democrats, 82 percent are satisfied with how the unions are representing their interests in politics. They are just as satisfied with politics as they are with collective bargaining. But Republicans see things very differently: 66 percent of them are dissatisfied with union politics -- the mirror opposite of how they feel about collective bargaining. This is a big number and well worth appreciating. Fully two-thirds of Republican members are politically alienated from their unions … By 45 to 29 percent, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say they would seek change by participating and speaking up. The great majority of Republicans, in fact, said they would do nothing to express their political disagreement -- 65 percent portrayed their “participation” in this way compared to 48 percent of Democrats. Republicans tend to respond to political disagreement by sitting on the sidelines. Thus when the Democrats' higher rate of participation is combined with their numerical advantage within the membership as a whole, the result is an internal voice process that they essentially own, outvoicing Republicans by more than three to one. To the extent that leaders have incentives to respond to the voices of ordinary members, then, these voices are heavily Democratic.

Indeed, a member of my local school board is a full-time employee for the American Federation of Teachers union, where she promotes “Share My Lesson,” a sub-group within the union that puts on annual online seminars teachers can watch to gain “professional development” credit toward job promotions (the website states “Share My Lesson’s live and on-demand webinars are eligible for continuing education credit and professional development points.”). I’ve watched many of these seminars, and written about some of them, which are dominated by encouragements to obsess about race to the exclusion of individual assessment and merit. And the American Federation of Teachers has even promulgated official policy positions opposing the presence of police officers in schools to help reduce school disruptions, and promoting policies that delay, if not prevent, the removal of disruptive students from classrooms so all the other students can learn. Such policies actually make the jobs of teachers much more difficult, but apparently that’s the price of having to work under the influence of politicized teachers unions that have had to make political alliance with a political party that promotes the same policies.

“Share My Lesson” is one of many websites where teachers can upload lesson plans on anything, and other teachers can download and use them as they wish. As Robert Pondiscio reports:

[O]ne of American education’s dirty little secrets: on any given school day in nearly every public school in the country, curriculum materials are put in front of children that have no official oversight or approval. It’s true that schools might have a state- or district-adopted curriculum, but that doesn’t mean it’s getting taught. Nearly no category of public employee has the degree of autonomy of the average public school teacher—even the least experienced ones. Teachers routinely create or cobble together their own lesson plans on the widely accepted theory that they know better than textbook publishers what books kids will enjoy reading and which topics might spark lively class discussions. Not your child’s school or teacher? Wanna bet? A 2017 RAND Corporation survey found that 99 percent of elementary teachers and 96 percent of secondary schools use “materials I developed and/or selected myself” in teaching English language arts. The numbers are virtually the same in math. But putting teachers in charge of creating their own lesson plans or scouring the internet for curriculum materials creates an irresistible opportunity for every imaginable interest group that perceives—not incorrectly—that overworked teachers and a captive young audience equal a rich target for selling products and pushing ideologies … Earlier this year, The Free Press’s Francesca Block broke news that PS 321 in Brooklyn, New York, sent kids home with an “activity book” promoting the tenets of the Black Lives Matter movement, including “queer affirming,” “transgender affirming,” and “restorative justice.” The book was not authorized for classroom use either by the NYC Department of Education or Brooklyn’s Community School District 15. It appears to have begun its journey into students’ backpacks at the massive “Share My Lesson” website run by the American Federation of Teachers, the nation’s second largest teachers union. The site claims 2.2 million members—more than half of all U.S. public school teachers—and hosts “more than 420,000 resources” that have been “downloaded more than 16 million times.” Lee & Low Books, the publisher of What We Believe, the BLM activity book, is a Share My Lesson “partner” and includes the book in its “anti-racist reading list for grades 3–5.” … A 2019 study published by the Fordham Institute rated most of the materials on Share My Lesson and Teachers Pay Teachers as “mediocre” or “probably not worth using.”

Regarding that study, its authors report:

[W]e set out to answer a simple question: are popular websites supplying teachers with high-quality supplemental materials? We recruited University of Southern California associate professor Morgan Polikoff to lead the review. He has conducted numerous studies on academic standards, curriculum, and assessments (including a previous Fordham study on Common Core–era tests), and he co-leads a federal research center on standards implementation. Jennifer Dean, an expert in assessment, standards alignment, and ELA content, served as lead reviewer of materials and assisted with report writing. She was joined by four other expert reviewers with backgrounds in teaching ELA, developing curricula and assessment items, and/or leading instructional teams … Sadly, the reviewers concluded that the majority of these materials are not worth using: more precisely, 64 percent of them should “not be used” or are “probably not worth using.” On all three websites, a majority of materials were rated 0 or 1 on an overall 0–3 quality scale … ReadWriteThink has the fewest errors [that might affect a student’s understanding] (mean = 2.92), while Share My Lesson has the most (mean = 2.53) and Teachers Pay Teachers is in the middle (mean = 2.79) … On a 0–3 scale, with 2 or higher corresponding to materials that reviewers thought teachers should use, the mean score for materials is 1.28, with reviewers recommending that 64 percent not be used or are probably not worth using. No website has a majority of materials earning an exceptional rating (Figure ES-3), but ReadWriteThink receives a slightly higher overall rating on average (mean = 1.41) than Share My Lesson (mean = 1.29) or Teachers Pay Teachers (mean 1.18).

Reviewers evaluated the extent to which multiday units introduced and sequenced knowledge in a way that allowed students to build their understanding of a topic. Of the units scored, 58 percent earned a 1 or 2 on this dimension, indicating that they support students’ ability to demonstrate such knowledge not at all or weakly.

Note that Share My Lesson is a product of the American Federation of Teachers union (Kelly Booz, a member of our local school board) is the director of Share My Lesson). The report notes that “Share My Lesson is a project of the American Federation of Teachers … It is the least used of the three websites under study [only 2% of teachers reported using it].”

As Pondiscio writes, “Absent regulations specifically requiring teachers to post all lesson plans and materials online on a daily basis, including material they create or find on the internet, it’s nearly impossible to say with any certainty what occurs inside the black box of the public school classroom.”

As Share My Lesson states in its official response to the 2019 report:

SML aims to be a crowdsourced resource-sharing website, which means that users can upload their best resources, and another user can add to or change them to meet the needs of their students. We do not edit the resources or provide instructions on how an educator should use a resource in the classroom. We also do not provide a lesson plan template, nor do we seek out any specific type of classroom resource. In other words, we are open to receiving any and all resources that teachers think could benefit another educator. SML is a response to what we heard from teachers. It was never intended to do the jobs of school district curriculum and instruction offices.

While collective bargaining is aimed at lowering standards for teachers, the teachers unions’ political agenda is aimed at reducing standards for students (including reducing penalties for homework not handed in), creating a perfect storm of bad policy that can only hurt the long-term prospects of the students such policies are allegedly designed to protect. This is especially so when research shows earnings are greater, and increasing in occupations that require “intellectual tenacity” (the ability to sustain mental effort over continuous stretches of time), with the researchers concluding:

that globally and in the US, the poor exhibit cognitive fatigue more quickly than the rich across field settings; they also attend schools that offer fewer opportunities to practice thinking for continuous stretches … Intellectual tenacity encompasses achievement/effort, persistence, initiative, analytical thinking, innovation, and independence. Social adjustment encompasses emotion regulation, concern for others, social orientation, cooperation, and stress tolerance. Both occupational personality requirements relate similarly to occupational employment growth between 2007 and 2019. However, among over 10 million respondents to the American Community Survey, jobs requiring intellectual tenacity pay higher wages—even controlling for occupational cognitive ability requirements—and the earnings premium grew over this 13-year period. Results are robust to controlling for education, demographics, and industry effects, suggesting that organizations should pay at least as much attention to personality in the hiring and retention process as skills.

Indeed, so entwined are teachers unions now with one political party’s agenda that a teacher strike in Oakland this year centered on “reparations” and “environmental justice.” As reported by Matt Feeney:

We parents aren’t feeling so communal about the Oakland teachers’ strike of 2023. The strike, which ran from 5 May to 15 May, wasn’t about the thing we were used to feeling invested in and guilty about — teachers’ pay. The parties (the teachers’ union and the Oakland school district) were close to agreement on a pay increase when the strike was called. What they continued to disagree on was a set of broad demands that, the union said, it was making on behalf of the “common good”. These demands sounded like an odd fit within a contract negotiation. Our kids had been kept home from school not because teachers were being ill-paid or disrespectfully treated, but because the leaders of their union had some theories about homelessness, social welfare, climate change and, of course, racism, along with some conspicuously swollen ambitions about how much policymaking power they might wrest from elected officials. The two most newsworthy of the union’s demands, and the most noteworthy to parents wondering how long their kids would be out of school, concerned racial reparations and environmental justice. From what we were hearing, the teachers wouldn’t return to work until our schools were remade into places where racial reparations are paid out and environmental justice is finally done.

The NEA teachers union even promotes a list of “Great Summer Reads for Educators” that includes Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, which was also recommended by a member of our own local school board who works for the AFT.

The latest figures show escalating political spending by teachers unions. As Elisabeth Messenger writes in the Wall Street Journal:

[O]nly 34% of its spending goes toward acting on behalf of its members. The AFT diverts large sums to political activities, supporting left-wing causes and candidates, taking no account of the diverse political affiliations among its members. Political spending accounted for 17.3% of the AFT’s total outlays in the 2021-22 fiscal year. AFT President Randi Weingarten pulls in roughly $488,000 a year—more than eight times what a teacher makes. The situation is arguably worse at the even larger National Education Association. It spent $49.2 million on political activities in 2021-22, surpassing the amount spent on membership representation by $3.5 million. Like the AFT, the NEA protected revenue from membership losses by hiking dues.

In contrast to how teachers unions treat teachers is the approach of the Houston Independent School District’s implementation of the “New Education System.” In a previous essay, we explored research on the great results shown in Dallas Independent School District’s Accelerating Campus Excellence program and its Principal Excellence and Teacher Excellence initiatives. The man who implemented these reforms, Mike Miles, was superintendent of Dallas ISD from 2012 through 2015, and, in May, was serving as the CEO of Third Future Schools. On June 1, 2023, following a state takeover of Houston Independent School District for poor performance, Miles was named the next superintendent of Houston ISD. He said the following in a podcast, explaining how centralizing a rigorous curriculum will dramatically help teachers teach and boost student learning, while treating teachers as “true professionals”:

We are providing lesson plans, demonstrations of learning, answer keys, the Powerpoint, the differentiated assignments for the teachers of the core subjects in the NES schools, so that teachers can come in and they’d start 15 minutes before class starts and they leave 15 minutes after and they are done. There’s a good work-life balance. We’re going to work them hard while they’re there, but they don’t have to make copies, they don’t have to make lessons, they don’t grade papers outside of class. We’re trying to treat them like true professionals.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine the large political imbalance that favors the rules promoted by teachers unions, to the detriment of concerns of parents and other people concerned about public education.