As Terry Moe writes in his book Special Interest: Teachers Unions and America’s Public Schools:

The teachers unions have traditionally been opposed to performance pay. As a recent New York Times article observed, “Unions offer a range of arguments against linking pay to what goes on in the classroom—that it is unhealthy for teachers to compete with one another, that they will cheat, that it is impossible to quantify good teaching, that the benefit to students is not proven, that all teachers deserve equal reward, that it allows management to play favorites. The bottom line is solidarity.” What the teachers unions strive for is a world of professional sameness, in which all teachers with the same experience and educational credentials are paid the same and all teachers see themselves as doing the same job and having the same interests.

As Michael Hartney writes in his book How Policies Make Interest Groups: Governments, Unions, and American Education:

I carry out a more focused case study that examines the teachers unions’ efforts to block teacher workforce policy (TWP) reforms their members oppose. TWPs broadly refer to the policies that states use to recruit, deploy, reward, evaluate, and retain teachers. TWPs offer a tough test of the blocking hypothesis because proposals to reform teacher pay and evaluation tend to be relatively popular with the public. Support for teacher performance pay, for example, has always been much higher among the public than with teachers. In 1958, a Gallup poll asked whether teacher pay raises “should be based on teaching ability or the length of service.” Seven out of ten Americans said ability. This result was no fluke. In four separate Gallup polls conducted since 1970 (one in each decade), more Americans said they would prefer to see teachers paid based on their performance rather than for their experience and credentials alone.

Yet teachers unions oppose pay for performance programs. As Hartney writes:

In 2019, for example, the NEA [National Education Association union] declared that “the single salary schedule is the most transparent and equitable system for compensating education employees.” Moreover, “[the NEA] opposes providing additional compensation to attract and/or retain education employees in hard to recruit positions ... and further believes that merit pay or any other system of compensation based on an evaluation of an education employee’s performance are inappropriate.”

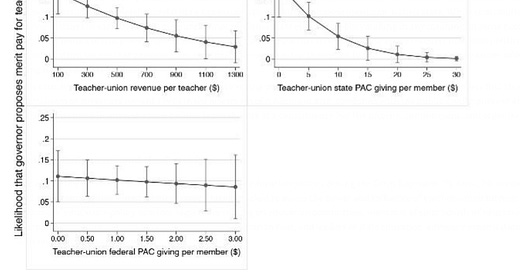

Hartney conducted a study in which he “controls for a governor’s party, Democratic control of the state legislature, and the ideological liberalism of the state’s electorate,” and finds that “as the political strength of unions in state politics increases, the likelihood that performance pay is proposed declines significantly. For example, governors from states where the average teacher-union affiliate had access to upwards of $1,000 in revenue per teacher and $10 per member in state PAC money have only a 5 percent probability of coming out in support of merit pay.”

Bucking the union-supported opposition to pay for performance is the city of Houston, Texas. As Moe writes, one “standout” is “Houston, which has put strong emphasis on student gain scores (and does not have collective bargaining).”

A recent study by over a half dozen researchers closely examined the Houston program and reported their findings in two papers. The first, titled “The Effects of Comprehensive Educator Evaluation and Pay Reform on Achievement,” reported the following:

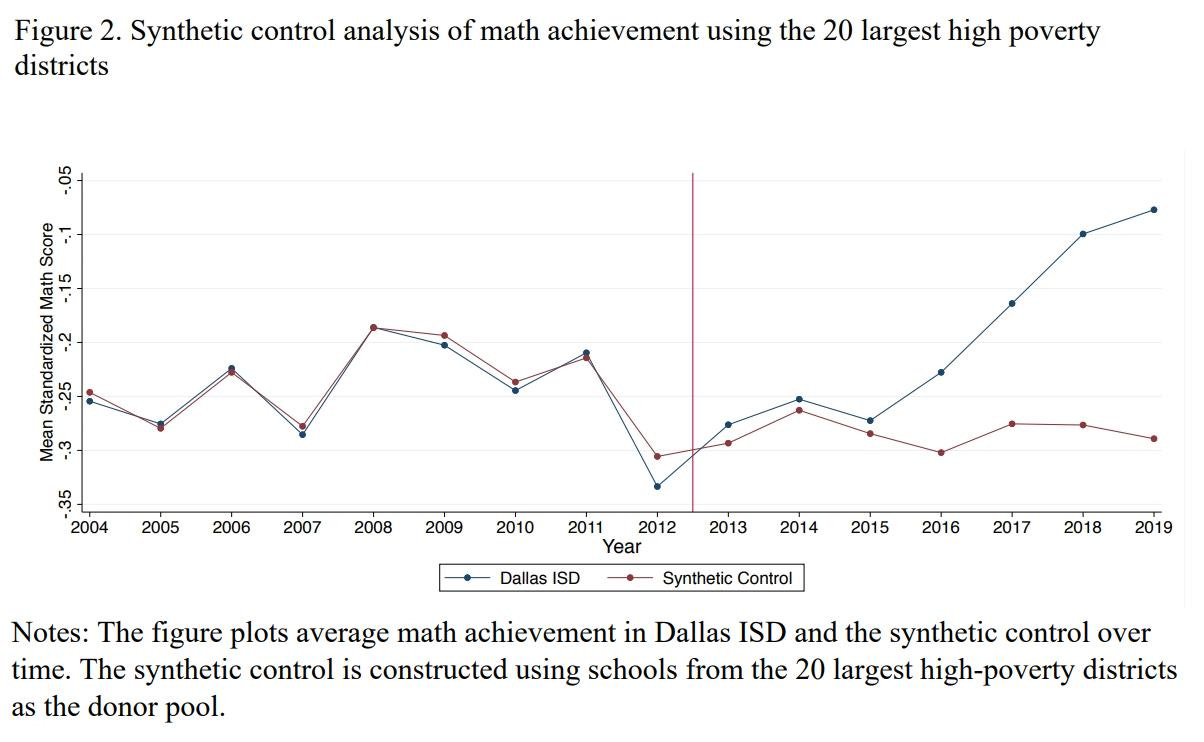

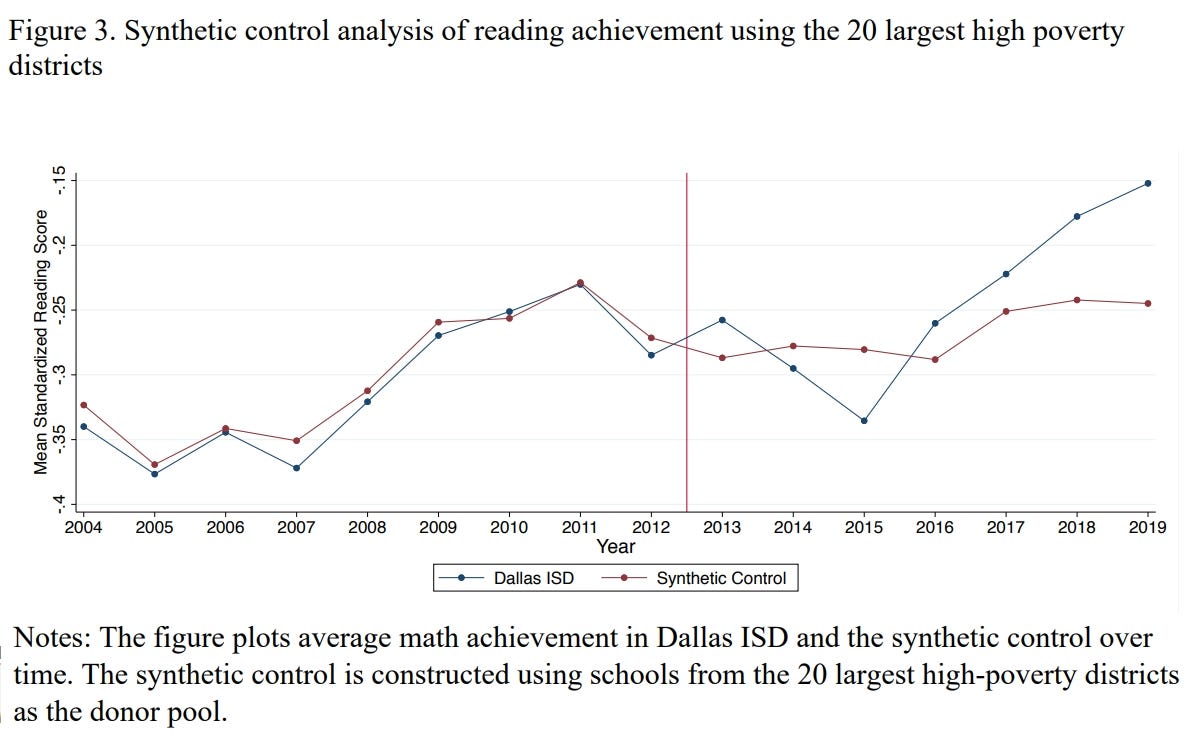

The Principal Excellence Initiative (PEI), implemented in 2013, and Teacher Excellence Initiative (TEI), implemented in 2015, introduced multiple-measure evaluation systems that align compensation with effectiveness and establish incentives for administrators to engage in rigorous evaluation and to support teacher improvement. Dallas ISD [Independent School District] has replaced salary scales based on experience and educational attainment with those based on evaluation scores, a radical departure from decades of rigid salary schedules. The district rates educators on the basis of their contributions to student achievement, supervisor observations and student or family feedback and uses the aggregate evaluation scores to place educators into ratings categories that are the primary determinant of salary. To protect the budget from tendencies toward evaluation inflation and deter the arbitrary treatment of teachers, the systems fix the distributions of teacher and principal ratings, and PEI includes a component that penalizes principals for a lack of alignment between their subjective teacher evaluations and effectiveness at raising achievement. In addition, the inclusion of school average achievement as a determinant of teacher evaluations is included to recognize the importance of teamwork, and consideration of progress toward reducing achievement gaps in principal evaluations provides incentives to focus on the least advantaged and students of color. Finally, district assessments have been developed to assess outcomes in grades and subjects that lack a state standardized test. The system has been modified in the years since adoption, but the foundational principles remain in place. After three years of discussion and development, the Teacher Excellence Initiative was approved by the Dallas ISD Board of Trustees in May 2014. It replaced the Dallas Professional Development and Appraisal System which used years of service and post-graduate schooling as the primary salary determinants; the system had been in place for 22 years. TEI dramatically alters the evaluation and compensation structures by requiring schools to collect far more information about teachers and to use the information for assessment, as the basis of professional development, and to set salary with some exceptions including educators in their first year in the district and some protections against salary decreases. The comprehensive personnel reforms introduced in Dallas ISD in 2013 including the virtual elimination of the dependence of salary on experience and post-graduate degrees radically altered systems of evaluation and pay that were representative of those used throughout the United States. System details reflect careful consideration of the potential for unintended consequences including evaluation inflation, the arbitrary treatment of teachers, and strategic responses including teaching to the test. Aligning the relationship between educator effectiveness and pay dramatically strengthened performance incentives, while the development of a multiple-measure evaluation system based on student outcomes, supervisor observations and student or family feedback recognized the pitfalls of a singular reliance on achievement or subjective evaluations by supervisors. Importantly, the focus on value added and achievement relative to comparable students rather than pass rate or achievement level in absolute terms made clear the effort to account for factors including family circumstances outside of educator control. The synthetic control analysis shows that the reforms succeeded in raising math and to a lesser extent reading achievement following an initial period of very high teacher turnover. Effect sizes exceeding 0.2 standard deviations for math and 0.1 standard deviations for reading are large, particularly in light of the minimal costs in comparison to interventions such as a large reduction in class size.

The program studied led to large gains in student math and reading standardized test scores:

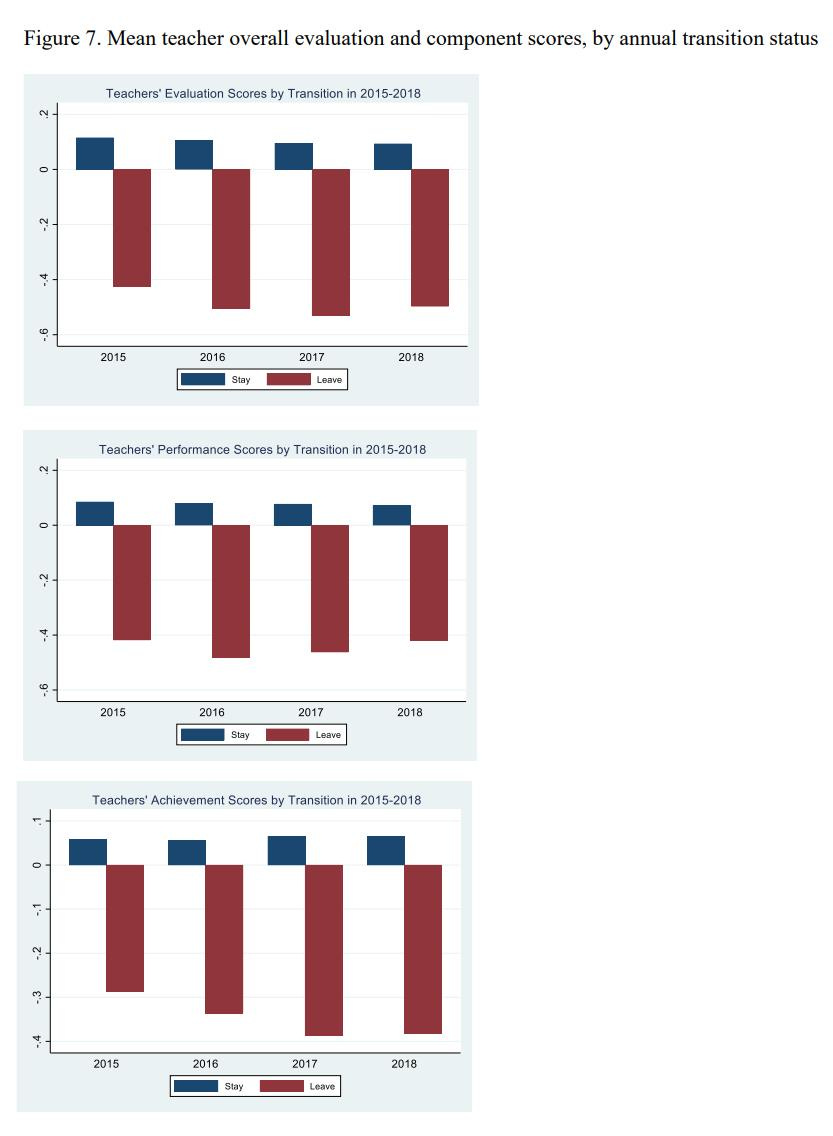

The program also led to teachers leaving the school based on their poor evaluations:

The second study of the Houston pay for performance program is titled “Attracting and Retaining Highly Effective Educators in Hard-to-Staff Schools.” That study reports the following:

Efforts to attract and retain effective educators in high poverty public schools have had limited success. Dallas ISD addressed this challenge by using information produced by its evaluation and compensation reforms as the basis for effectiveness-adjusted payments that provided large compensating differentials to attract and retain effective teachers in its lowest achievement schools. The Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE) program offers salary supplements to educators with records of high performance who are willing to work in the most educationally disadvantaged schools. We document that ACE resulted in immediate and sustained increases in student achievement, providing strong evidence that the multi-measure evaluation system identifies effective educators who foster the development of cognitive skills. The improvements at ACE schools were dramatic, bringing average achievement in the previously lowest performing schools close to the district average. When ACE stipends are largely eliminated, a substantial fraction of highly effective teachers leaves, and test scores fall. This highlights the central importance of the performance-based incentives to attract and retain effective educators in previously low-achievement schools.

Two of the researchers involved with the studies, Eric Hanushek and Steven Rivkin, said the following regarding their studies during an American Enterprise Institute podcast on the subject:

Eric Hanushek: This is Texas … There is no collective bargaining in Texas, and so it’s a situation that gives [the school system] a fair shot at trying to change things …

Host: Eric, how do teacher compensation systems typically work?

Eric Hanushek: You record how many years of experience you have as a teacher and whether you have an advanced degree, and you look it up in a table of what your salary is, so that compensation systems have evolved to very standard payments for experience and degrees but not much for anything else.

Regarding the pay for performance program in Houston:

Eric Hanushek: After four years of both systems being in effect, the Dallas District started to come close to an average district in the whole state, and they have a much more disadvantaged population. So what you saw was, instead of being the standard disadvantaged central city school where students are performing below the state significantly, they’re coming up close to that. But another way of looking at this is that the 0.2 standard deviations [improvement] are somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of a year extra schooling, it’s like kids were all of a sudden after this time learning at a rate that brought them up two-thirds to three-quarters of a whole grade level.

Despite the evidence of the benefits of teacher pay for performance, as noted in the Wall Street Journal, in 2024, teachers unions in New York succeeded in eliminating reforms that required school districts to consider student performance in teacher evaluations:

This being an election year, Democrats are looking to reward their union allies. Look no further than New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who recently signed a bill repealing hard-won school reforms. The new law reverses changes to teacher tenure and evaluations that were negotiated in 2015 … It repeals a mandate that districts consider student performance in teacher evaluations. Districts were also allowed to use expedited procedures to remove tenured teachers who received two consecutive “ineffective” ratings and were required to do so for those who rated poorly three years in a row.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine how teachers unions are treating teachers not as professionals, but as political activists.

This seems so obvious. The money these people pour into Democrats is so distorting it is mind blowing. Thanks for exposing all this.