One of the strangest perceptions that’s become popular in some quarters is that the presence of police doesn’t actually reduce crime. As I’ve mentioned in a previous essay, lots of research has shown that, lo and behold, the presence of police does indeed reduce crime.

As a result, one would expect the presence of police in schools would reduce the incidence of infractions in schools as well. That certainly seems to have been learned the hard way where I live in Alexandria, Virginia, when police were temporarily banned from public schools by an activist majority of our local city council (who decided to redirect the $800,000 that had been used to pay for police in schools to pay for “additional mental health professionals” instead), and as a result there was a marked increase in school violence.

The debate over police in schools shows another vast disconnect between, on the one hand, urban city council and school board politicians and teachers union officials and, on the other hand, the general public and teachers.

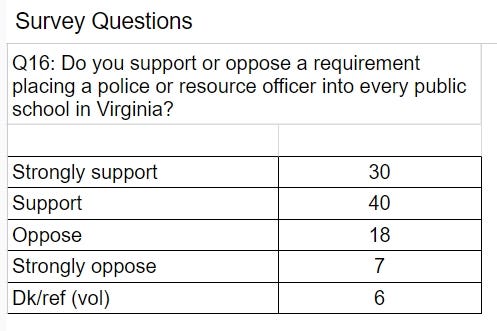

The official policy of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) union, for example, is that police should be banned from schools. In 2020, the AFT passed a resolution that states “RESOLVED, that the necessary function of school safety should be separated from policing and police forces.” However, over two-thirds of Virginians (where I live) support requiring police in every public school.

A large poll of teachers also found overwhelming support for the presence of police officers in public schools. Education Week, which conducted the poll, reported that:

[T]he EdWeek Research Center conducted a survey June 17-18 of 1,150 teachers, principals, and district leaders. It found that most educators … oppose measures to remove armed police officers from schools … [M]ost of the rank-and-file educators who responded to the EdWeek Research Center survey oppose the removal of armed police officers from schools. Just 23 percent say that armed police officers should be eliminated from our nation’s schools—although support for severing ties with law enforcement ranges from 36 percent in the Northeast to 13 percent in the southern United States … The perception that armed officers belong in local schools is significantly more common among high school teachers and principals (67 percent) than among those who work in elementary schools (51 percent). It’s also more prevalent among teachers, principals, and district leaders in large districts with 10,000 or more students (69 percent) than in smaller districts with less than 2,500 students (41 percent) …

[N]early 3 out of 4 teachers, principals, and district leaders say that they need armed school police officers in case someone comes into the building with the intent of doing harm to students and staff … Thirty percent of survey respondents say that they need armed police officers in their schools because too many students are out of control. This view is much more common among teachers (39 percent) than among principals (20 percent) or district leaders (22 percent) … A little more than half of survey respondents (58 percent) believe the country would have more deaths from school shootings if armed police officers were eliminated from schools …

[T]he vast majority of survey respondents who work in districts where armed police officers are stationed at schools strongly believe that those officers treat students of color fairly …

The poll also found that “fewer than 1 in 4 teachers, principals, and district leaders (23 percent) believe that armed police officers contribute to the “school-to-prison” pipeline by disproportionately arresting/ticketing students of color. The percentage of educators who share this belief ranges from 17 percent in the South to 33 percent in the Northeast.”

Of course, if, as the data show, the presence of police officers reduces the commission of crimes and other infractions, then one would expect that fewer, not more, people would be referred to the police when police are present, thereby putting the lie to the argument that there’s a “school-to-prison pipeline.” And that’s exactly what research shows.

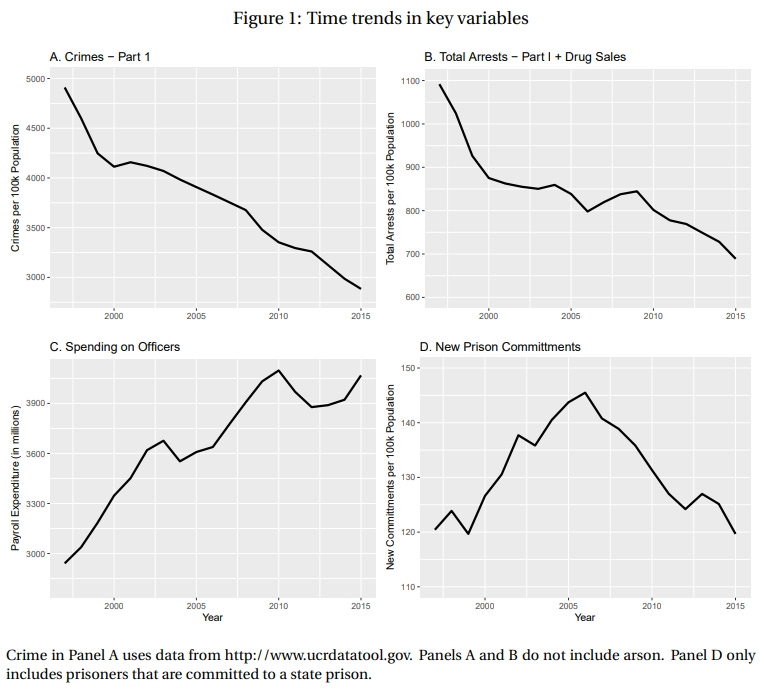

Emily Greene Owens, in her entry on Cops and Cuffs in Lessons from the Economics of Crime: What Reduces Offending?, examined the random roll-out of hiring grants from the Department of Justice’s COPS Program to estimate the marginal impact of police hiring on the number of arrests made. She reported that “The main finding is that hiring more police officers does not necessarily result in more arrests for serious crimes, and does not appear to have resulted in higher levels of incapacitation overall.” This, of course, is not surprising if the very presence of police deterred people from engaging in arrestable behavior.

And researchers at the University of Pennsylvania concluded that:

A large literature establishes that hiring police officers leads to reductions in crime and that investments in police are a relatively efficient means of crime control compared to investments in prisons. One concern, however, is that because police officers make arrests in the course of their duties, police hiring, while relatively efficient, is an inevitable driver of “mass incarceration." This research considers the dynamics through which police hiring affects downstream incarceration rates. Using state-level panel data as well county-level data from California, we uncover novel evidence in favor of a potentially unexpected and yet entirely intuitive result — that investments in law enforcement are unlikely to markedly increase state prison populations and may even lead to a modest decrease in the number of state prisoners. As such, investments in police may, in fact, yield a “double dividend” to society, by reducing incarceration rates as well as crime rates.

By the same logic, fewer kids will be reported to the police when fewer kids will have committed infractions when deterred by the presence of the police.

And when fewer students engage in disruptive conduct, all students benefit, especially those who would benefit most from a safe school environment, namely students from low-income or single parent families. As I discussed in a previous essay, it’s the presence of disruptive and violent students, not the presence of the police who would deter such disruptions and violence, that can ruin the educational experience of all the other students around them, with researchers finding that children who were exposed to an above-average (within-school) concentration of disruptive peers in elementary school have much lower-than-predicted future earnings, and that adding one disruptive peer to a class of 25 will result in earnings reductions of over 3 percent.

Why do some politicians ignore the logic that more police means less crime, which in turn means fewer referrals to the criminal justice system? As Dr. Tony Sewell, the former Chair of the United Kingdom’s Race and Ethnic Disparities Commission, said, referring to such politicians, “They’re actually frightened of solutions. And they want the narrative to continue in that negative way, because it suits them. It suits their profile, their finance and, maybe even to a certain extent, their psychology.” Dr. Sewell, the son of Jamaican immigrants to Brixton, England, made those comments in the context of his work on the Commission:

[Tony Sewell] had produced a landmark report that concluded that the “claim the country is still institutionally racist is not borne out by the evidence.” The 258-page report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities (CRED), led by Sewell, [concluded] that racism is a “real force” in Britain, but that it is no longer a country where the “system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities” … A year on, and the leading educationalist believes the most vocal critics hadn’t even bothered to read the report – let alone understand it. “They wanted the narrative of the white world against us and anything else wouldn’t do at that time,” he says. “When we came along with all our data, showing that this was a bit more complex, they didn’t want to hear that. Nobody was reading the recommendations. They just wanted to know whether we were talking about issues to do with white privilege or institutional racism. ‘Were you on the side for this or not?’ – that’s all they wanted to know. And if you were not, then you were cancelled … We had a team [made up] of 95 per cent ethnic minorities going at this, and we were just led by the data …” Speaking on behalf of himself and his fellow nine commissioners, only one of whom is white, he adds: “… I’m worried about the fact that, in that community, there are people there who don’t want solutions.”

In many ways, the tendency of politicians to blame police for all manner of disparities among people grouped by race denies the ability of those people to make moral decisions for themselves. Yale Law Professor Peter Schuck has written that:

John Ogbu and other educational researchers … have pointed to an “oppositional culture” among many black students that manifests itself in less time spent on homework, high rates of truancy, elevated drop-out rates, and greater indiscipline. The latter in particular harms classroom learning for other students and has increased teacher attrition rates in many urban schools, which further undermines educational progress in black neighborhoods. The remedies for these conditions are elusive, but they surely lie to a large extent within the black community and black families.

Indeed, as the United Kingdom’s Report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities notes:

It has been quite a journey of discovery. As we [the Commission] met with people in round table discussions … and listened to people from all sections of society, we were taken by the distinctions being drawn between causes that were external to the individual and those that could be influenced by the actions of the individual himself or herself. As our investigations proceeded, we increasingly felt that an unexplored approach to closing disparity gaps was to examine the extent individuals and their communities could help themselves through their own agency, rather than wait for invisible external forces to assemble to do the job.

As the British Commission found, the very key to reducing disparities among groups based on race may well be to recognize moral agency within individuals.