Higher Taxes Can’t Be the Answer – Part 1

The already large tax burden on most taxpaying-Americans today.

In previous essays I described how Congress is enacting more and more entitlement welfare benefits to cover more and more categories of people, including the young and middle class (thereby increasing federal debt), while at the same time a smaller percentage of Americans are participating in the labor force and fewer Americans are having children (thereby reducing the pool of taxpayers who could pay for that increasing federal debt). In this series of essays, I’ll discuss why “taxing the rich” can’t be a solution to the problem of paying for ever-increasing federal spending by taking from an ever-shrinking tax base.

Taxes are about as old as civilization. As Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod write in their book Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom: “The Rosetta Stone describes a tax break given to the temple priests of ancient Egypt, reinstating tax privileges they had enjoyed in prior times.” And while the news today remains dominated by stories about the COVID-19 pandemic, tax policy remains ever-relevant to all our lives. As the humorist H.L. Mencken once wrote, “Taxation… is eternally lively; it concerns nine- tenths of us more directly than either smallpox or golf, and has just as much drama in it …”

Before looking at more recent proposals to increase federal taxes, let’s first examine the baseline for comparison, namely the state of tax policy, and its rationale, as it has existed in recent decades, and centuries.

The first sections of the following essays will discuss the tax system in America prior to enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017. The latter part of these essays will discuss the effects of the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, as that data has become available. Once we’ve covered that ground, we’ll have more context within which to evaluate the merits of demerits of the more recently proposed federal “Build Back Better Act.”

The Burden on the Individual Taxpayer

Researchers have set up a website listing, for each state, the amount of taxes the average American can be expected to pay in their lifetimes. They highlighted the following findings:

The average American will pay $525,037 in taxes throughout their lifetime.

That’s an average of 34.3% of all lifetime earnings spent on taxes.

Residents of New Jersey will pay the most in lifetime taxes ($931,000) and people in West Virginia will pay the least ($321,000).

Tax on earnings is where most tax will come from, with the average American paying $339,173 in a lifetime.

Owning a car will cost an additional $29,521 in tax payments alone.

Tax on property will set you back an additional $128,581 above the property price and maintenance.

Aggregate Taxes Paid

The tax policies of today’s modern industrial countries, including those of the United States, take as much from the people as regimes of old. The author who was a prime inspiration for the American Revolution, Thomas Paine, wrote “What at first was plunder assumed the softer name of revenue,” and ancient and modern regimes have all exploited their ability to enforce tax laws. As Keen and Slemrod write:

Perhaps one-tenth of national product went to the state in Periclean Athens; possibly one-third in the early Abbasid caliphate; and at least one-third in Ottoman Egypt at the end of the sixteenth century. In Tokugawa Japan (1603–1867), 30 percent or more of rice output was taken in tax throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; about one-quarter of the national produce went to the Imperial government in early Mughal India; and about the same amount was collected by the United Provinces of the Netherlands in 1688. These figures are not far off today’s average tax take in advanced economies of around one-third of GDP … For the United States, federal receipts are also much the same as they were in 1947, at around 16 percent of GDP; adding state and local taxes brings that to about 26 percent of GDP.

Visualizing Taxes Paid

This “Tax Freedom Day” calendar illustrates the cost of government by dividing all federal, state, and local taxes by the nation’s income. In 2013, Americans paid $2.76 trillion in federal taxes and $1.45 trillion in state taxes, for a total tax bill of $4.22 trillion, or 29.4 percent of income. Everything Americans earned from January 1 to April 18 of 2013 went to pay these various taxes. So Americans work about a third of the time exclusively to pay government taxes.

This calendar is striking to many largely because their taxes are subject to tax withholding, a process under which the taxes people owe are taken out of their paychecks even before they receive those paychecks, largely hiding the impact of taxation from them. As Keen and Slemrod write:

Withholding made the mass income tax possible. That proved to be a source of regret for one of its main architects in the United States, who did live to see his handwork in action: Milton Friedman, the Nobel-prize winning advocate of small government. “It never occurred to me,” he later bemoaned, “that I was helping to develop machinery that would make possible a government that I would come to criticize severely as too large, too intrusive, too destructive of freedom.” … “Only by taking people’s money before they ever see it,” said Republican Dick Armey, “has the government been able to raise taxes to their current height without sparking a revolt.”

The Wartime Roots of the Modern Income Tax Regime

The federal income tax wasn’t popular outside of a wartime context until after World War I. As Keen and Slemrod describe the early history:

The idea of a federal income tax was first floated in 1815, but the war with the British ended before it came to anything. It was another war, the Civil War—and the enormous cost of waging it—that triggered its first incarnation. The North (but not the South) attempted an income tax in the first year of the conflict, 1861, championed in Congress by the appropriately named William Pitt Fessenden. Before it went into effect, Congress met again and drafted a new income tax law, in which the single rate was just 5 percent, raised in 1864 to 10 percent … It was never a mass tax: In 1866, tax was due from only about 450,000 people … With the war’s end, however—revenues from other sources being buoyant, and the national debt falling—there was no appetite for its continuation, and the tax expired in 1872.

The original Constitution didn’t empower Congress to enact an income tax, and early attempts by government to collect an income tax were successfully challenged in the courts, with the top lawyer for the plaintiff mounting such a challenge telling the Supreme Court in the early 1900’s “that if this ‘communistic march’ were not summarily halted, nothing would prevent future action by Congress to increase ‘the tax from two percent to ten percent, or to twenty percent.’”

But momentum built for adoption of a constitutional amendment to allow for a federal income tax just before World War I, with anti-alcohol Prohibitionists leading the charge, as “many prohibitionists believed that taxes on alcohol legitimized the alcohol business, and that the revenues it produced—about 30 percent of all federal receipts in 1910—made the government an invisible partner in the immoral business, unwilling to see it founder.”

Then, among the many horrors of World War I, was its role in the history of high tax policies. The income tax was ramped up significantly to help pay for the war, and it’s never been ramped down much since. As Keen and Slemrod write:

In the United States, swelling popular support for an income tax … led first to a modest tax on corporations and then to a constitutional amendment in 1913 that allowed a federal income tax. These pressures were as nothing, however, compared to the massive increase in taxation in the belligerents once the First World War began … The top rate of the U.S. income tax rose from 7 percent when it was introduced in 1913 to 77 percent in 1918 … The Second World War proved even more transformative, with the income tax becoming for the first time something that applied to most ordinary people: In the United States, for example, the number of income tax returns filed soared from 7.7 million in 1939 to 49.9 million in 1945. This expansion was made possible by a critical advance in tax administration: the massive use of withholding—getting the employer to remit tax rather than trying to obtain it directly from the employee.

The Republican chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee at the time of enactment of the first federal income tax, Sereno Payne

contended that an income tax would make “a nation of liars” and be “a tax on the income of the honest men …” Strong words. But they actually came from a supporter of the tax, which Payne saw as essential for the country to raise money in the event of war. In a similar vein, Congressman Cordell Hull argued that America would be “helpless to prosecute … any … war of great magnitude” without taxing “the wealth of the country in the form of incomes.” Both sides, it seemed, had absorbed the lesson of Pitt the Younger, having war finance in mind years before any specter of major conflict.

In the beginning, the federal income tax

was modest enough, with a tax of 1 percent on net income and surtax rates of 1 to 6 percent, the last kicking in at $500,000 of income (so the top rate was 7 percent). Each taxpayer having an exemption of $3,000, only a little over 350,000 returns were filed in 1913 and 1914,64 from a population of just under 100 million. During the debate, Republican Congressman Ira C. Copley proposed—as a warning—graduating the rates to a maximum of 68 percent on income over $1,000,000, predicting that “within 10 years some such law will be written on the statute books of this country by the American Congress.” (Copley, it turned out, was too timid—it took 4 years, not 10.)

This is America’s first income tax form, in its entirety.

In 1940, instructions for federal tax forms ran two pages. By 2013, they ran to 207 pages.

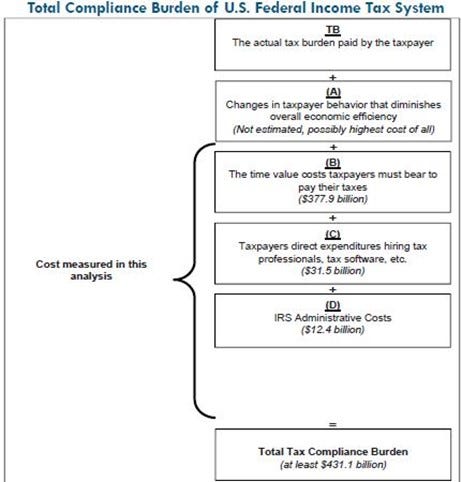

Today, the federal income tax has become so complex that it’s been estimated to cost Americans well over $400 billion a year just to comply with it.

In the next essay, we’ll look beyond the costs of complying with the tax code, to the much larger hidden costs of taxation’s “excess burdens,” which few of us, and even fewer policymakers, tend to consider.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8