Higher Taxes Can’t Be the Answer – Part 4

Even progressive tax policies supporting welfare spending can hurt the least well-off.

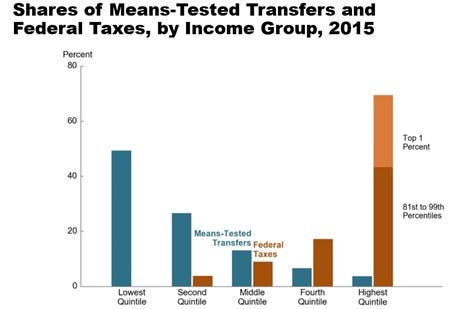

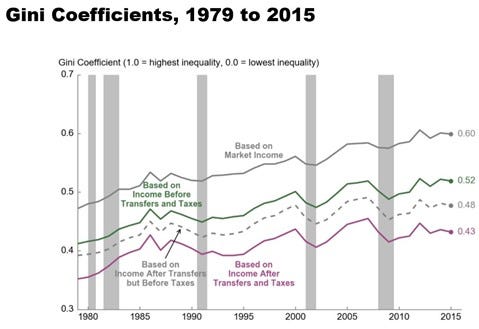

In November, 2018, the Congressional Budget Office presented the following charts and graphs, showing, from 1979 to 2015, the income growth among all quintiles after transfers and taxes, average federal tax rates by income group and tax source, the share of means-tested transfers and taxes by income group, average federal tax rates by income group, and lower income inequality (measured by the “Gini Coefficient”) after transfers and taxes are considered. What these graphs show is that the incomes of people within all income quintiles have risen over time, that the rich have paid an increasingly greater share of their income in taxes, that the lowest income quintiles have received increasingly greater payments from entitlement and welfare programs, that federal tax rates for middle and lower income quintiles have gone down over time, and that income inequality has remained relatively constant over time when income transfers and taxes paid are taken into account.

Still, while our progressive tax structure is intended to make the rich pay their “fair share” and contribute to programs designed to benefit the worse-off, the “excess burdens” caused by the tax structure can end up significantly diminishing the beneficial effects of those tax policies. As Keen and Slemrod write:

The idea is that which group it is that ends up bearing the burden of a tax depends on the relative ease with which all those involved can find some alternative to the taxed activity … [P]eople who consume or produce taxed activities for which there are few good alternatives end up holding the tax bag … It is the people with the fewest alternatives that tend to get stuck with most of the tax burden.

These economic ripple effects often significantly dilute any benefits intended to be accrued to the worse-off through tax policy. As Keen and Slemrod explain:

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is the main policy tool used in the United States to alleviate poverty while encouraging work, with several other countries now having their own variant. It works as a subsidy on low earnings by providing a credit against income tax due that turns into a cash payment to the earner if the credit exceeds the liability (and is then withdrawn at higher income levels). In 2020, for example, the EITC provided an annual credit for a household with three children of up to $6,660. Does the EITC stick and, as intended, benefit low-income workers? Maybe not completely. By making work more attractive, the EITC induces an increase in labor supply among low-income workers. Unless the demand for their labor is perfectly inelastic (meaning, improbably, that employers will employ the same amount of labor no matter what wage they have to pay), this increase in labor supply drives wages down. To the extent that wages fall, the benefit of the EITC to the intended beneficiaries—low-income, often low-skill, workers—is reduced, and some of the intended transfer redounds to employers. Moreover, low-skill workers who do not receive the EITC are hurt even more, because—as they compete with the workers who do receive it—they receive the lower wages but do not get the credit … One estimate is that for every dollar that single mothers receive from the EITC, they ultimately lose $0.30 through lower wages. Employers of low-skill labor capture a whopping $0.73 per dollar: $0.30 of this decline coming from those EITC-eligible single workers and another $0.43 from workers who are not EITC-eligible but whose wages nevertheless fall. The net transfer to all low-skill workers, considering both those who get the EITC and those who do not, is, according to this study, just 27 (that is, 100 minus 73) cents per dollar of the EITC. The risk that measures intended to improve the lot of the poor can end up benefiting, maybe even more, the better-off, is a recurrent one.

And current federal welfare and entitlement spending is so large that it will have to be paid for eventually by middle class Americans, not just “the very rich.” Beyond the comparative figures used in previous essays that described the already steeply progressive nature of the American tax system, let’s look at raw numbers. Even if the federal government confiscated all of the taxable income of everyone in the U.S. making more than $100,000 a year back in 2008, it would have collected only $3.4 trillion, which was less than a quarter of the current total national debt of over $16 trillion. (And if all that money were collected that year, it would of course not be available to be taxed in years thereafter.)

Lord North, the Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782, recognized long ago that any large expenditures by government were ultimately going to have to be paid for by the large majority of the people, not just “the rich.” As Keen and Slemrod write:

Lord North, while recognizing that the first call should be on the better off, also saw the sad mathematical reality that “where great sums were to be borrowed the burden must lie upon the bulk of the people” (“borrowing” here being something of a euphemism for “collected”).

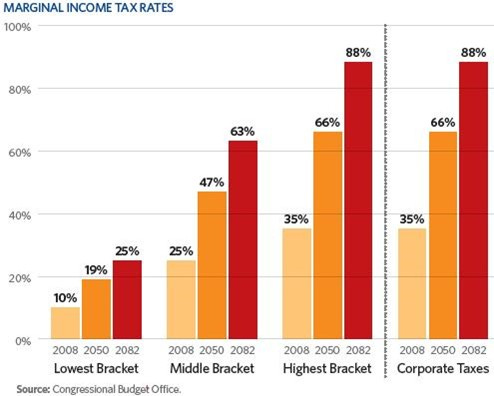

Ten years ago, when federal spending was much lower, in order to just balance the yearly federal budget amid rising entitlement spending through tax increases alone, the marginal income tax rates of all income brackets (and corporate taxes) would have to have risen dramatically over time.

To do the same thing by increasing tax rates on taxpayers in the two highest brackets alone would have required increasing their tax rates to mathematically impossible levels. To close the 2035 deficit, the top two tax rates would have had to increase to 159 percent and 166 percent, and in 2050 they would have to increase 236 percent and 246 percent.

With greater government spending comes greater government debt, and that debt represents a future tax that will have to be paid at some point. As Keen and Slemrod write, “a government’s ability to borrow ultimately rests on its ability to tax. Debt, that is, is really just a promise of deferred taxation.”

Some people say the federal government can always just print more money to pay for increased government spending, in lieu of taxes, with some going so far as to suggest the government simply mint trillion dollar coins to pay for it. But today, the federal government, through the Federal Reserve banking system, doesn’t have to print new dollar bills to increase the money supply. It just has to lower the interest rates for borrowing money. As Keen and Slemrod remind us:

When banks get to borrow from the central bank at a lower rate, they pass these savings on by reducing the cost of loans to their customers. Lower interest rates tend to increase borrowing, and this means the quantity of money in circulation increases … [L]iterally “printing money” is not the only way that money can be directly created, or even, these days, the main one: The central bank can simply create electronic credits in the accounts that commercial banks hold with it. To the extent that it pays interest on those accounts at a rate lower than that it receives on the assets it acquires, this also provides a source of finance for the government (being the owner of the central bank).

But adding money to the money supply, of course, can cause inflation, in which prices rise because more money is chasing goods and services. And as Keen and Slemrod write:

Such increases in the price level act like a tax, and one that creates clear winners as well as losers. The losers are those who hold assets, or receive income, denominated in the debasing currency. “By a continuing process of inflation,” wrote the British economist John Maynard Keynes, “governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens.” … Trying to cover an unsustainably large excess of public spending over tax revenue by printing money (or today’s digital equivalent) can lead to massive inflation.

And inflation hurts the poor the most, who are least able to pay higher prices.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8