Higher Taxes Can’t Be the Answer – Part 5

Some misconceptions about corporate and historic tax rates.

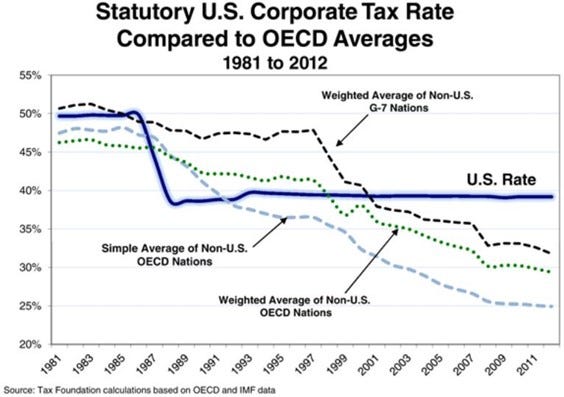

Looking at corporate tax rates, in the early 2010’s, the U.S. had the highest corporate tax rate among all the G-7 Nations and the 34 countries in the OECD.

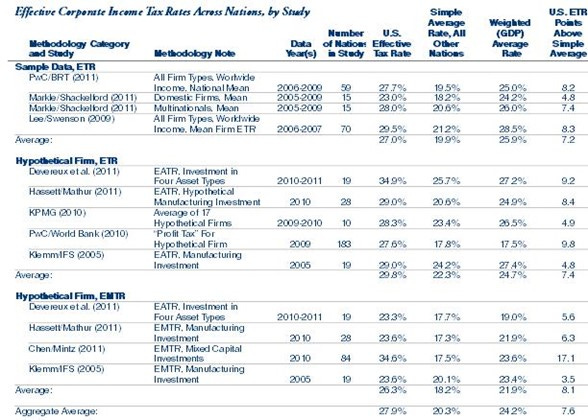

The U.S. retained its relatively high corporate tax rate even after tax credits and deductions are considered to determine the effective tax rate (ETR).

In 2013, in an international study ranking countries for their tax attractiveness to corporations using an index of 16 different factors, the U.S. ranked near the very bottom.

Excess tax burdens (described in a previous essay) follow from corporate income tax rates as well as individual tax rates. And those excess burdens fall disproportionately on lower-income working people. As Keen and Slemrod write:

The incidence of the corporation tax, as will be seen shortly, is far from clear in principle and far from settled as a matter of fact. But wherever it ends up, the burden must be on actual people … So, what do the principles laid out above tell us about the likely incidence of the corporate tax? To apply them, start with what a typical corporate tax does. It taxes profits that are calculated as revenues minus the costs of doing business, including among these costs depreciation allowances for investment purchases and interest paid … To the extent the tax reduces the return they earn in the corporate sector below the minimum they need, it will lead them to invest elsewhere. It could be, for example … that investors will instead put their money abroad … In either case, the burden of the corporate tax may fall not on the plutocrats, but (again) on the hard-working stiffs they employ … In 2013, the U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation—responsible for estimating the distributional impact of federal tax proposals—allocated 75 percent of the burden of corporate income taxes to owners of capital in the long run, with the remainder mostly borne by labor. Using a similar method, the Congressional Budget Office as of 2010 similarly allocates 25 percent of corporate income taxes to labor in its long-run estimates, while the Department of the Treasury allocates 18 percent … [T]hose concerned with workers’ welfare who assume that a tax on corporations falls only on those who own the corporations risk doing their cause a disservice.

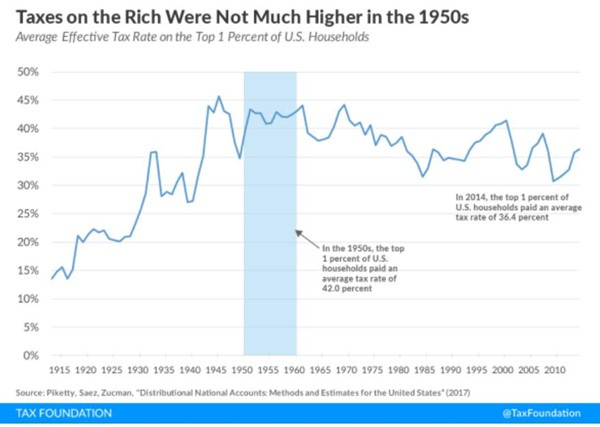

Finally, as a researcher at the Manhattan Institute has pointed out, there’s a misimpression among many people that the rich paid a lot more in federal taxes in the past, and that increasing tax rates for the rich would simply be a return to what tax rates “are supposed to be.” But the rich didn’t actually pay more taxes in the past:

Progressives have often reminded us that the U.S. had such [high tax] rates in the past. From 1936 to 1980, the highest federal income-tax rate was never below 70%, and the top rate exceeded 90% from 1951 to 1963. Under Ronald Reagan, the top federal rate declined to 28% by 1988 and has never reached 40% since. The discussion of these rates can easily create the impression that the federal government collected far more money from ‘the rich’ before the Reagan administration. And it can also leave another impression: There would be no downside to raising rates to 1950s levels, given that decade’s prosperity. Neither impression would be correct. The effective tax rates actually paid by the highest income earners during the 1950s and early ’60s were far lower than the highest marginal rates. Few taxpayers reached the top brackets, the code was rife with loopholes, and capital gains were taxed at much lower rates. In the 1960s, for example, the average rate paid by the top 0.1% of tax filers -- the top 10th of the top 1% -- ranged from 26.5% to 29.5%, according to a 2007 study by Messrs. Piketty and Saez. Even during the 20 years after the Reagan tax cuts, the top 10th of the top 1% paid an average rate of 23.7% to 33% -- essentially the same as in the 1960s. In the decade following 2001, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the average rate for this elite group never exceeded 32%. Nostalgia aside for a world that never existed, few people paid the top tax rates of the 1950s and early 1960s. Of course, when they did, the top marginal rates applied only to income above a very high threshold.

The following chart illustrates this data.

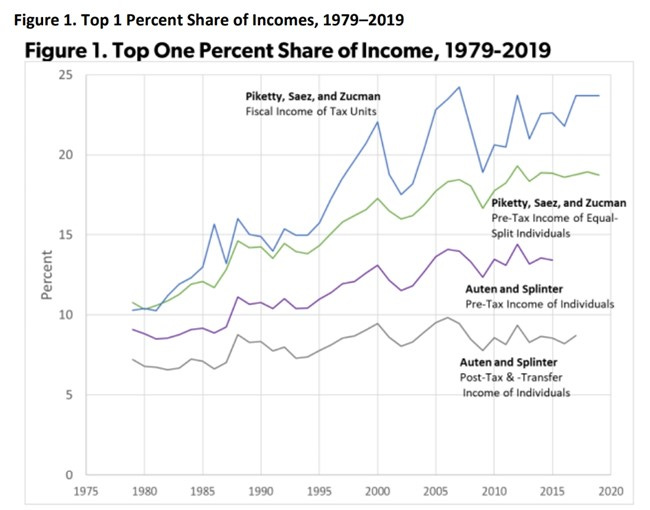

As Scott Winship has further pointed out, another common misimpression was created by widely-cited estimates by Thomas Piketty of the share of pretax income received by the top 1 percent, which were used to justify proposed tax increases. In fact, Piketty’s estimates

have been effectively challenged by two government economists, Gerald Auten and David Splinter … After improving the pretax estimates, Auten and Splinter found that the top 1 percent’s share [of pretax income] rose from only 9 percent in 1979 to 13 percent in 2015, and after fully accounting for taxes and transfers, the top share rose from just 7 percent in 1979 to 9 percent in 2017 (Figure 1). To be clear: The narrative of soaring income inequality that was featured in policy debates and presidential campaigns for two decades has been based on badly mismeasured estimates of income concentration.

In sum, corporations and the richest Americans pay steeply progressive taxes already, and pushing rates for corporations and the richest Americans even higher risks deterring them from generating the greater productive economic growth on which ever-increasing federal entitlement spending relies. Those economic dynamics will be explored in the next essay.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8