Higher Taxes Can’t Be the Answer – Part 7

The likely results if the Build Back Better Act had been enacted.

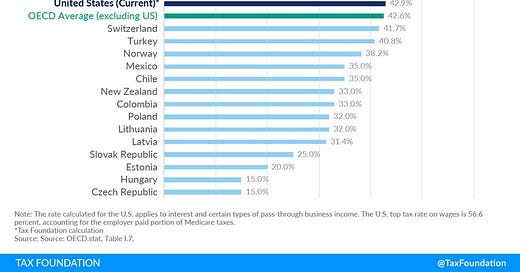

Although it failed to pass the Senate, it’s worth considering what would have been the fiscal ramifications if Congress had passed the latest iteration of the House’s Build Back Better Act (BBBA), under which the average top tax rate on personal income would have reached 57.4 percent, giving the U.S. the highest rate of all countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Under the BBBA, all 50 states plus the District of Columbia would have had top tax rates on personal income exceeding 50 percent.

As the Tax Foundation points out, if the BBBA had been enacted into law:

High-income taxpayers would face a surcharge on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), defined as adjusted gross income less investment interest expense. The surcharge would equal 5 percent on MAGI in excess of $10 million plus 3 percent on MAGI above $25 million, for a total surcharge of 8 percent. The plan would also redefine the tax base to which the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT) applies to include the “active” part of pass-through income—all taxable income above $400,000 (single filer) or $500,000 (joint filer) would be subject to tax of 3.8 percent due to the combination of NIIT and Medicare taxes. Under current law, the top marginal tax rate on ordinary income is scheduled to increase from 37 percent to 39.6 percent starting in 2026. Overall, the top marginal tax rate on personal income at the federal level would rise to 51.4 percent.

In addition to the top federal rate, individuals face taxes on personal income in most U.S. states. Considering the average top marginal state-local tax rate of 6.0 percent, the combined top tax rate on personal income would be 57.4 percent—higher than currently levied in any developed country. This assumes the deduction for state and local taxes remains capped. If we assume the cap for the state and local tax deduction is lifted, the average top marginal state-local tax rate would fall to 54 percent. Eight states plus the District of Colombia would face top tax rates higher than 60 percent. Taxpayers in New York and California would face the highest tax rates, at 66.2 percent and 64.7 percent respectively. Even in the eight states that forgo an income tax, such as Florida and Nevada, taxpayers would have a top rate of 51.4 percent, which far exceeds the top rates found in most OECD countries.

With all that said, would it have been a good thing or a bad thing if the BBBA had been enacted into law?

As a general matter, high taxes discourage work and capital formation. Data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggest that a 1% increase in a nation’s tax rate is associated with a 1.4% decrease in hours worked per person in the working-age population, and U.S. data dating to the 1970’s also shows that higher taxes cause workers to limit their hours, reducing economic output.

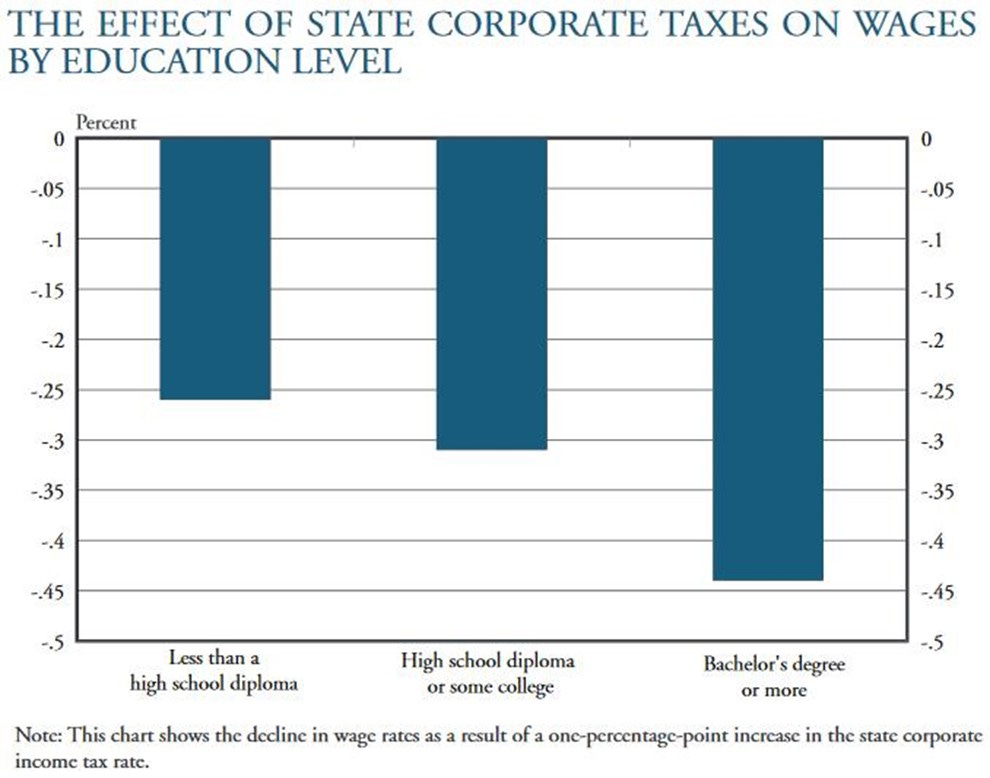

Higher corporate taxes also reduce the return to capital, making capital move abroad and reducing employment. And just as a sales tax has an impact on the final price of goods, a higher corporate tax has an impact on wages. Wages go down when corporate taxes go up, and so reducing corporate tax rates boost wages.

Increases in corporate tax rates are passed on directly to workers in the form of lower wages. As the Wall Street Journal points out:

The great political fakery [behind calls for higher corporate taxes] is that corporate taxes merely fall on CEOs and rich shareholders. But as everyone knows, corporations don’t really pay taxes. They are vehicles for collecting taxes that are ultimately paid by some combination of customers in higher prices, workers in lower wages, and shareholders in lower returns on investment. The economic literature is clear on this point. Kevin Hassett, Aparna Mathur, Laurence Kotlikoff and other economists have done extensive work showing how lower corporate tax rates result in higher wages. Higher after-tax profits mean more corporate investment, which means more productive workers, whom companies can afford to pay more.

While the CEOs and other individuals pay income taxes like other people do, as Phil Gramm and Mike Solon explain in the Wall Street Journal, the “corporation” itself doesn’t pay any taxes (rather, the customers and the workers end up paying those “corporate” taxes):

Corporate tax rates, which were the driving force behind the permanent part of the 2017 tax cuts, receive less attention than individual income-tax rates only because Americans don’t understand that corporations don’t pay taxes. A corporate entity is a “pass through” legal structure—a piece of paper in a Delaware filing cabinet. When the corporate tax rate increases, corporations try to pass the cost on to consumers. To the degree that the entire cost of the tax increase can’t be passed on to consumers, those costs are borne by employees and investors. Most economic studies conclude that 50% to 70% of a corporate tax increase not passed on in higher prices is borne by workers, while 30% to 50% is borne by investors. If you consume, you pay the corporate tax. If you consume and work for a corporation, you pay the corporate tax twice. If you consume, work and invest your retirement funds in corporate equities, the corporate tax rate hits you three times. Democrats call up the image of the greedy robber baron as a personification of big corporations, but when you pull back the curtain, it isn’t the wizard or the robber baron you see but yourself as a consumer, worker and pensioner. Many Americans don’t pay individual income taxes, but all Americans pay corporate taxes. In fact, a recent Treasury study confirms that 92.6 million families, 49.5% of all American families, pay more in corporate taxes than they do in individual income taxes. Unfortunately Americans consistently underappreciate the burden the corporate income tax imposes, especially on middle- and low-income Americans. President Biden’s proposed corporate tax increases would raise taxes on more low- and moderate-income American families than if he raised individual income-tax rates.

When one considers a number of reasonable adjustments to the compensation calculation, such as using compensation rather than wages, by including workers in managerial and professional positions, and by using a more inclusive measure of earnings, compensation (as opposed to just wages) is tending to rise with growth in the gross domestic product.

And a large amount of evidence suggests that raising taxes lowers gross domestic product. Researchers have concluded that marginal rate cuts lead to both increases in real GDP and declines in unemployment. And Christina Romer (former Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under the Obama Administration) and David Romer have concluded that “an exogenous tax increase of 1 percent of GDP lowers real GDP by roughly 2 to 3 percent.”

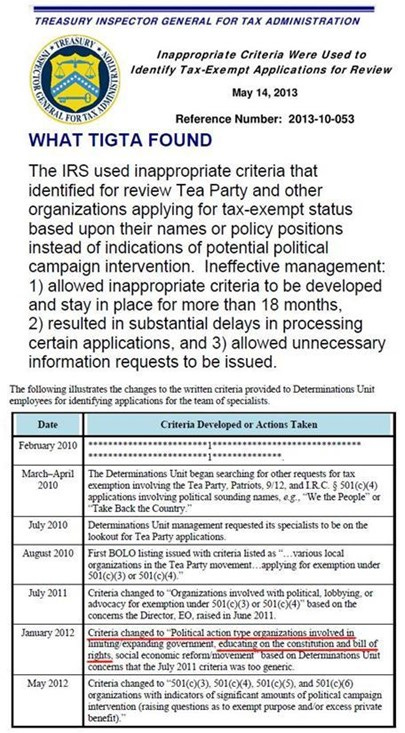

It’s also worth noting that the Build Back Better Act would have provided significantly more funding to the Internal Revenue Service for tax enforcement, a power that’s been shown to be subject to serious political abuse. A May 14, 2013 report by the Treasury Inspector General found that organizations that were involved in “educating on the constitution and bill of rights” were singled out for adverse tax treatment by the Internal Revenue Service.

Other groups with “Progressive” in their name were not subject to the same adverse treatment.

That adverse treatment by the IRS may have significantly affected the 2012 presidential election. An analysis by Stan Venger at the American Enterprise Institute found that:

In a new research paper, Andreas Madestam (from Stockholm University), Daniel Shoag and David Yanagizawa-Drott (both from the Harvard Kennedy School), and I set out to find out how much impact the Tea Party had on voter turnout in the 2010 election. We compared areas with high levels of Tea Party activity to otherwise similar areas with low levels of Tea Party activity, using data from the Census Bureau, the FEC, news reports, and a variety of other sources. We found that the effect was huge: the movement brought the Republican Party some 3 million-6 million additional votes in House races. That is an astonishing boost, given that all Republican House candidates combined received fewer than 45 million votes. It demonstrates conclusively how important the party’s newly energized base was to its landslide victory in those elections, and how worried Democratic strategists must have been about the conservative movement’s momentum. The Tea Party movement’s huge success was not the result of a few days of work by an elected official or two, but involved activists all over the country who spent the year and a half leading up to the midterm elections volunteering, organizing, donating, and rallying. Much of these grassroots activities were centered around 501(c)4s, which according to our research were an important component of the Tea Party movement and its rise. The bottom line is that the Tea Party movement, when properly activated, can generate a huge number of votes-more votes in 2010, in fact, than the vote advantage Obama held over Romney in 2012. The data show that had the Tea Party groups continued to grow at the pace seen in 2009 and 2010, and had their effect on the 2012 vote been similar to that seen in 2010, they would have brought the Republican Party as many as 5 – 8.5 million votes compared to Obama’s victory margin of 5 million. President Obama’s margin of victory in some of the key swing states was fairly small: a mere 75,000 votes separated the two contenders in Florida, for example. That is less than 25% of our estimate of what the Tea Party’s impact in Florida was in 2010. Looking forward to 2012 in 2010 undermining the Tea Party’s efforts there must have seemed quite appealing indeed.

Unfortunately for Republicans, the IRS slowed Tea Party growth before the 2012 election. In March 2010, the IRS decided to single Tea Party groups out for special treatment when applying for tax-exempt status by flagging organizations with names containing “Tea Party,” “patriot,” or “9/12.” For the next two years, the IRS approved the applications of only four such groups, delaying all others while subjecting the applicants to highly intrusive, intimidating requests for information regarding their activities, membership, contacts, Facebook posts, and private thoughts. As a consequence, the founders, members, and donors of new Tea Party groups found themselves incapable of exercising their constitutional rights, and the Tea Party’s impact was muted in the 2012 election cycle.

This nefarious use of the tax system is old indeed. As Keen and Slemrod write:

There is … a dark side to taxes motivated by other than a need for money. From the medieval taxes on Jews, through Cromwell’s decimation tax and the 1930s taxes on chain stores, and up to the whiff of revenge in calls for taxation of bankers’ bonuses following the Global Financial Crisis, taxes have been used to punish enemies and reward friends.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8