“Disparate Impact” -- Part 7

The overlooked role of median age in disparate impacts among people grouped by race.

As we’ve explored in previous essays, some people make the false claim that all disparities among people grouped by race are due to racism, when in fact many other variables explain those disparities. In this essay, we’ll look at another especially important but often overlooked factor in disparities among people grouped by race, namely differences in median age.

The median age of a racial group can also significantly affect group outcomes. As Thomas Sowell explains in Discrimination and Disparities:

Among the most overlooked factors in socioeconomic outcome differences, both within nations and between nations, are such demographic factors as differences in median age. These differences are not small, and neither are their consequences. In the United States, for example, income differences between middle aged people and young adults are larger than income differences between blacks and whites. Moreover, these income differences among age groups have increased over time, as the physical vitality of youth has become less valuable economically with the replacement of human muscle power by mechanical and electrical power, while the development of human capital—knowledge, skills and experience—has become more valuable, with the development of more advanced technologies and more complex organizations. Ethnic and other social groups differ in median ages by as much as two decades or more. In the United States, for example, the median age of Japanese Americans is 51 and the median age of Mexican Americans is 27. How likely is it that these two groups—or others—would have the same proportions of their populations equally represented in occupations, institutions or activities requiring long years of education and/or long years of job experience? Is it surprising if Hispanic Americans are not as well represented as Japanese Americans in the professions, or in managerial careers, for which long years of education and experience are usually required? How many 27-year-olds of any ethnic background meet the requirements for being CEOs in civilian life or generals and admirals in the military? A group with a median age in their twenties will obviously not have nearly as large a proportion of their population with 20 years of work experience as a group whose median age is in their forties. One group may therefore have a disproportionate number of people in high level occupations requiring long years of experience, while the other group may be similarly over-represented in professional sports or in violent crimes, both of which are activities disproportionately engaged in by the young … Even if Japanese Americans and Mexican Americans were absolutely identical in everything else besides age, they would nevertheless differ significantly in incomes and other age-related outcomes. Racial, ethnic and other groups are of course seldom, if ever, identical in everything else. That makes the prospects of equal outcomes even more improbable, and disparities in outcomes even more questionable as automatic indicators of discrimination. In terms of capabilities, a man is not even equal to himself at different stages of life, much less equal to the wide range of other people at varying stages of their own respective lives. In these circumstances, equal rights and equal treatment of all does not mean equal performances—and virtually guarantees unequal performances and outcomes.

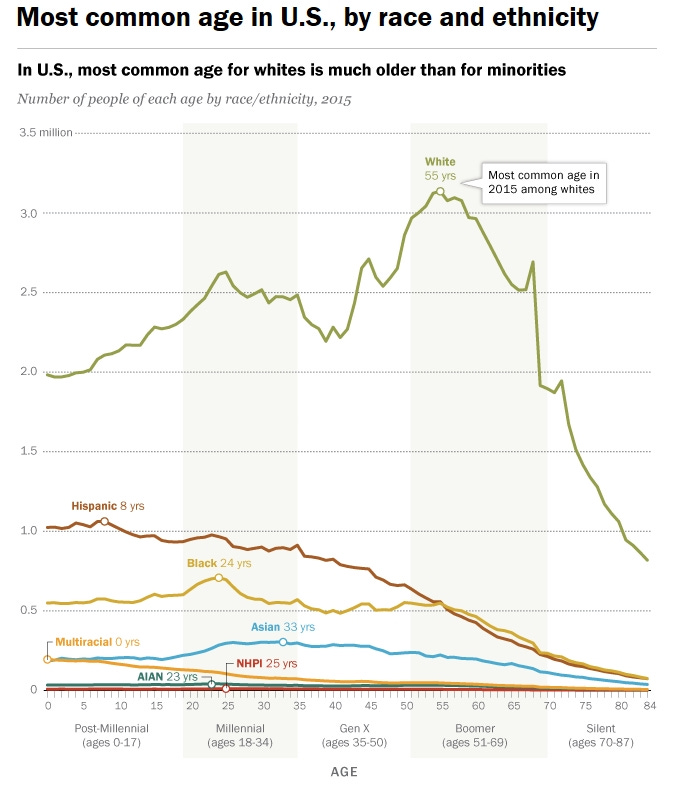

An example of how median age differences can help explain particular disparities, but are often ignored by government regulators, is the rate of possession of drivers’ licenses. For example, in 2011, the Obama Administration Department of Justice sent a letter declining to “preclear” South Carolina’s law requiring voters to show an ID law. In that letter, the Department claimed that “minority registered voters were nearly 20% more likely to ... be effectively disenfranchised” by the law because they lacked a driver’s license. But the difference between white and black holders of a driver’s license was only 1.6 percent. The Justice Department used the 20% figure because, while the state’s data showed that 8.4% of white registered voters lacked any form of DMV-issued ID, as compared to 10.0% of non-white registered voters, the number 10 is 20% larger than the number 8.4. It’s true mathematically that 10 is 20% larger (actually, 19% larger -- the Justice Department rounded up) than 8.4, but it clearly distorts the reported difference in driver’s license rates, and it was used to declare the South Carolina law racist. But what other factors might then explain differences in outcomes among demographic groups? There are thousands of potential explanations, but one primary explanation is that whites, as a group, have a higher median age than other minority demographics, meaning whites will generally have more accumulated resources and work experience, which will lead to some differences in general outcomes.

Further, and directly relevant to the South Carolina voting law example, data show that younger people among both blacks and whites tend to be the least likely to have drivers’ licenses. Consequently, if blacks have proportionately more young people in their demographic group, there will be a disproportionate number of blacks without drivers’ licenses.

A similar analysis relates to the incidence at which black Americans have interactions with the police in speeding stops. As Thomas Sowell explains:

Another violation of the law that can be tested and quantified, independently of the police, is driving in excess of highway speed limits. A study by independent researchers of nearly 40,000 drivers on the New Jersey Turnpike, using high-speed cameras and a radar gun, showed a higher proportion of black drivers than of white drivers who were speeding, especially at the higher speeds. This study, comparing the proportion of blacks stopped by state troopers for speeding with the proportion of blacks actually speeding, was not nearly as widely accepted, or even mentioned, by either the media or by politicians, as other studies comparing the number of blacks stopped by state troopers for speeding and other violations with the proportion of blacks in the population. Yet again, specific facts have been defeated by the implicit presumption that groups tend to be similar in what they do, so that large differences in outcomes are treated as surprising, if not sinister. But demographic differences alone are enough to lead to group differences in speeding violations, even aside from other social or cultural differences. Younger people are more prone to speeding, and groups with a younger median age tend to have a higher proportion of their population in age brackets where speeding is more common. When different groups can differ in median age by a decade, or in some cases by two decades or more, there was never any reason to expect different groups to have the same proportion of their respective populations speeding, or to have the same outcomes in any number of other activities that are more common in some age brackets than in others … Seekers of “social justice,” in the sense of equal or comparable outcomes, proceed as if eliminating racial bias, sex bias or other group bias would produce some approximation of that ideal outcome. But what of the implications of the fact that a majority of the people in American prisons were raised with either one parent or no parent? People in groups where many children grow up in single-parent homes do not have the same probability of being incarcerated as people who grow up in groups where single-parent homes are rare. But those who believe in the invincible fallacy may believe that the problem originated where the incarceration statistics were collected, in the criminal justice system.

Crime rose in predominantly black urban centers when a disproportionately large number of younger people came to live there. As William Julius Wilson writes in his 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged:

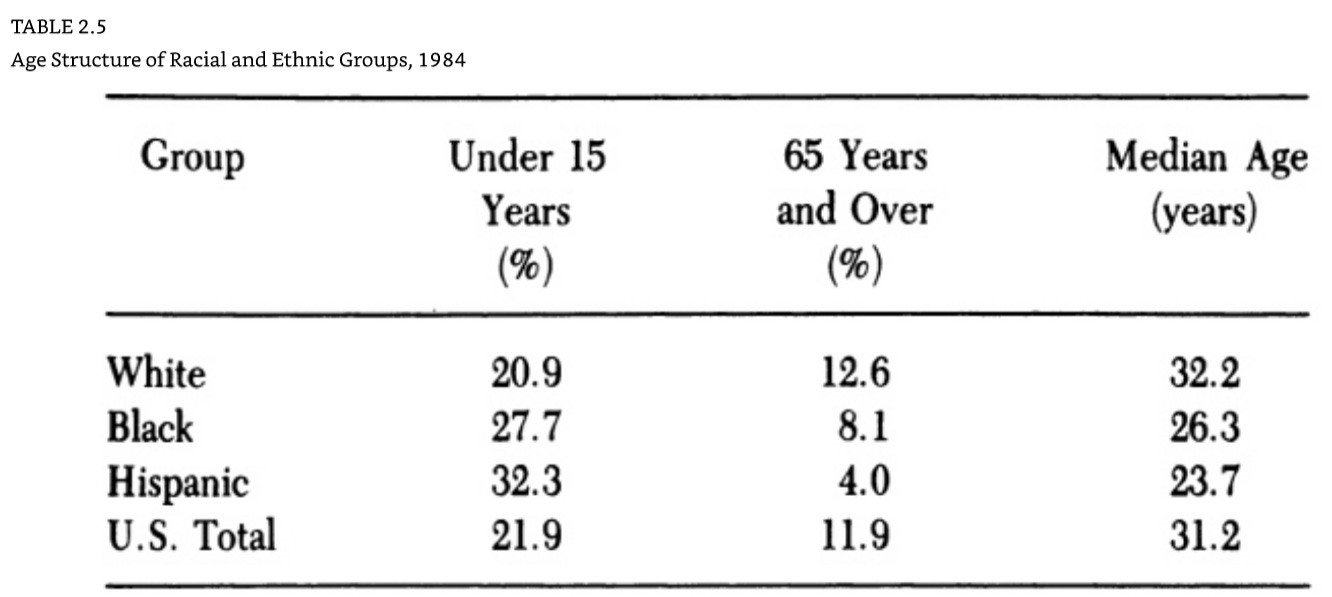

[T]he black migration to urban centers— the continual replenishment of urban black populations by poor newcomers— predictably skewed the age profile of the urban black community and kept it relatively young. The higher the median age of a group, the greater its representation in higher income categories and professional positions. It is therefore not surprising that ethnic groups such as blacks and Hispanics, who on average are younger than whites, also tend to have high unemployment and crime rates. As revealed in table 2.5, ethnic groups differ markedly in their median age and in the proportion under age fifteen.

In the nation’s central cities in 1977, the median age for whites was 30.3, for blacks 23.9, and for Hispanics 21. One cannot overemphasize the importance of the sudden growth of young minorities in the central cities. The number of central-city blacks aged fourteen to twenty-four rose by 78 percent from 1960 to 1970, compared with an increase of only 23 percent for whites of the same age. From 1970 to 1977 the increase in the number of young blacks slackened off somewhat, but it was still substantial. For example, in the central cities the number of blacks aged fourteen to twenty-four increased by 21 percent from 1970 to 1977 and the number of Hispanics by 26 percent, while whites of this age-group decreased by 4 percent. On the basis of these demographic changes alone one would expect blacks and Hispanics to contribute disproportionately to the increasing rates of social dislocation in the central city, such as crime. Indeed, 66 percent of all those arrested for violent and property crimes in American cities in 1980 were under twenty-five years of age … [Harvard professor James Q.] Wilson states that the “increase in the murder rate during the 1960s was more than ten times greater than what one would have expected from the changing age structure of the population alone” and “only 13.4 percent of the increase in arrests for robbery between 1950 and 1965 could be accounted for by the increase in the numbers of persons between the ages of ten and twenty-four.” Speculating on this problem, Wilson advances the hypothesis that an abrupt rise in the number of young persons has an “exponential effect on the rate of certain social problems.” In other words, there may be a “critical mass” of young persons in a given community such that when that mass is reached or is increased suddenly and substantially, “a self-sustaining chain reaction is set off that creates an explosive increase in the amount of crime, addiction, and welfare dependency.” … The importance of this jump in the number of young minorities in the ghetto, many of them lacking one or more parents, cannot be overemphasized. Age correlates with many things. For example, the higher the median age of a group, the higher its income; the lower the median age, the higher the unemployment rate and the higher the crime rate (more than half of those arrested in 1980 for violent and property crimes in American cities were under twenty-one). The younger a woman is, the more likely she is to bear a child out of wedlock, head up a new household, and depend on welfare. In short, part of what had gone awry in the ghetto was due to the sheer increase in the number of black youth.

In the next essay, we’ll explore further how false claims that disparate impacts among people grouped by race are due to racism helps obscure the real progress experienced among all people.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9

Brilliant. Thank you.