“Disparate Impact” – Part 2

How disparate impact claims caused the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

In this essay, we’ll look at how the legal theory of disparate impact played a significant role in the 2007-2008 financial crisis that was caused when a large number of people found themselves unable to pay the home loans they had committed to pay. We’ll also look at how claims of disparate impact also played a significant role in creating the situation today in which kids are expected to go to college to get a good job, even when, as we’ve seen in previous essays, going to college doesn’t pass a cost-benefit analysis for many people.

While there were many pressures on mortgage lenders to relax the standards under which loans were extended in the 1990’s, one factor was the Clinton Administration Justice Department’s aggressive pursuit of disparate impact claims. The Clinton Administration pursued those claims in the mortgage lending field as well, making allegations that lenders’ facially neutral credit criteria had a disparate adverse impact on the availability of mortgages to certain covered groups, including those in low-income communities.

Peter Mahoney wrote in the Emory Law Journal in 1998 that

The federal agencies charged with enforcing the Fair Housing Act (FHA) and the ECOA [Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974] have adopted an aggressive approach to enforcement of the fair housing and fair lending laws in the last four years. In particular, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have suggested interpretations of the case law that would impose a more rigorous standard of disparate impact liability on private party defendants such as lenders, insurers and landlords. [Citing Policy Statement on Discrimination in Lending, 59 Fed. Reg. 18,269 (April 15, 1994).]

Stephen Dane also wrote in the Banking Law Journal in 1998 that

Lenders relying on written standards and criteria in making decisions as to whether to grant a residential mortgage loan application run the risk of exposure to liability under the civil rights law doctrine known as disparate-impact analysis … The concept of disparate impact is of particular significance to lenders, who often rely on written standards and criteria to decide whether to grant or deny a residential mortgage loan application. If those guidelines, policies, or practices operate to exclude racial minorities or other protected groups at a rate substantially higher than nonprotected categories of persons, the lender may be exposed to liability under several civil rights laws … Let’s take an example. A lender operating in the Philadelphia housing market has a policy of not extending loans for single-family residences valued at less than $45,000. Such a policy, if uniformly applied, would exclude 67 percent of the homes located in minority neighborhoods (defined as greater than 50 percent minority) in the Philadelphia area. In contrast, only 6 percent of the homes located in white neighborhoods (defined as less than 25 percent minority) would be affected. The policy has a substantial disparate impact on minority neighborhoods in Philadelphia … Under precisely what conditions will a particular policy or practice be found to constitute a ‘business necessity’? There is no clear answer to be found. But a review of the reported decisions under the Fair Housing Act reveals that very few fair housing defendants have ever been able to establish a business necessity in a disparate-impact case … Several underwriting guidelines that are fairly common throughout the mortgage lending industry are at risk of disparate-impact analysis [including] creditworthiness standards …

Courts at the time had held that the Fair Housing Act prohibited lenders from employing practices that have a disparate impact based on race. At the same time, in order to alleviate disparate impacts in lending, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council suggested to lenders, in a document entitled “Home Mortgage Lending and Equal Treatment: A Guide for Financial Institutions” in 1991, that rather than focusing on credit history as defined in a credit report, such lenders should focus on evidence of a borrower’s ability and willingness to repay a loan, including a record of regular payments for utilities and rent.

The threat of such lawsuits pressured lenders to extend more mortgages to low-income communities so disparate impact lawsuits could be avoided. Economists have suggested that these relaxed lending standards were a prime cause of the current financial crisis because many loans were extended to people who could not reasonably be expected to be able to pay them back. Stan Liebowitz wrote that

in an attempt to increase homeownership, particularly by minorities and the less affluent, an attack on underwriting standards was undertaken by virtually every branch of the government since the early 1990s. The decline in mortgage underwriting standards was universally praised as an ‘innovation’ in mortgage lending by regulators, academic specialists, GSEs [Government Sponsored Enterprises], and housing activists. This weakening of underwriting standards succeeded in increasing home ownership and also the price of housing, helping to lead to a housing price bubble.

As Thomas Sowell writes in Social Justice Fallacies:

One of the major factors in the housing boom and bust, which produced an economic crisis in the United States, early in the twenty-first century, was a widespread belief that there was rampant racial discrimination by banks and other lending institutions against blacks applying for mortgage loans. Various statistics from a number of sources showed that, although most black and white applicants for conventional mortgage loans were approved, black applicants were turned down at a higher rate than white applicants for the same loans. What was almost universally omitted were statistical data showing that whites were turned down for those same loans more often than Asian Americans. Nor was there any great mystery as to why this was so. The average credit rating of whites was higher than the average credit rating of blacks— and the average credit rating of Asian Americans was higher than the average credit rating of whites. Nor was this the only economically relevant difference. Nevertheless, there were outraged demands in the media, in academia and in politics that the government should “do something” about racial discrimination by banks and other mortgage lenders. The government responded by doing many things. The net result was that it forced mortgage lenders to lower their lending standards. This made mortgage loans so risky that many people, including the author of this book, warned that the housing market could “collapse like a house of cards.” When it did, the whole economy collapsed. Low-income blacks were among those who suffered. The same question can be raised about mortgage approval patterns as the question about hiring and firing in the job market. Were predominantly white mortgage lenders discriminating against white applicants? If that seems highly unlikely, it is also unlikely that black-owned banks were discriminating against black mortgage loan applicants. Yet black applicants for mortgage loans were turned down at an even higher rate by a black-owned bank.

Even the Washington Post editorialized that “the problem with the U.S. economy … has been government’s failure to control systemic risks that government itself helped to create. We are not witnessing a crisis of the free market but a crisis of distorted markets … [G]overnment helped make mortgages a purportedly sure thing in the first place.”

While the prevailing media narrative points to greedy mortgage lenders and financial traders as the source of the 2007-2008 economic crisis, data indicate it was caused in significant part by the federal government’s backing of risky home loans for people who could not reasonably be expected to pay their mortgages, evidenced by their low credit scores and high debt burdens. (The Community Reinvestment Act is a federal law designed to encourage banks to loan more money to those with low incomes.)

As Peter Wallison of the American Enterprise Institute explains:

The government’s affordable housing goals required that a certain number of the mortgages acquired by the GSEs (government-sponsored enterprises, namely Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) each year be made to borrowers who were at or below the median income in their communities. At first, the quota was 30 percent -- that is, in any year, 30 percent of all mortgages bought by the GSEs had to be made to these borrowers. There were also other special goals for low-income borrowers and minorities. HUD was given authority to increase these goals, and it did so, aggressively, between 1996 and 2008. [This chart] shows the increases in the goals. The top set of lines are the low- and moderate-income (LMI) goals; the two lower sets of lines are special goals for underserved (i.e., minority) borrowers and very-low-income borrowers (80 percent or 60 percent of median income).

The result:

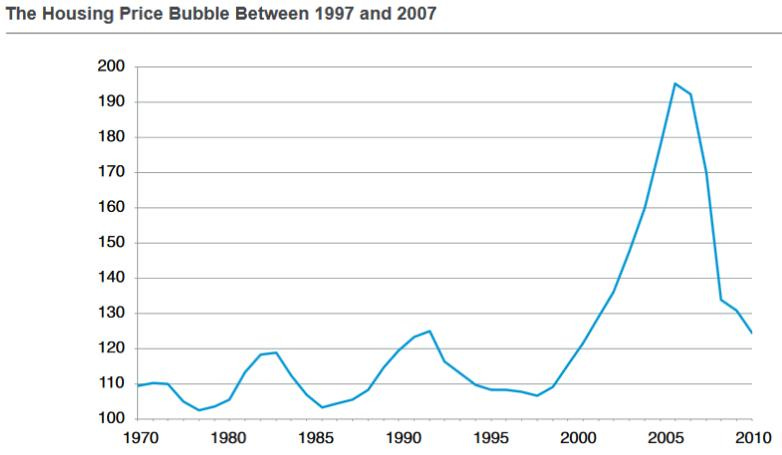

The increases in the goals had a major effect on the GSEs’ underwriting standards. Before the goals were enacted, the GSEs generally bought only prime mortgages (a prime mortgage had a 10–20 percent down payment, a borrower credit score above 660, and borrower debt-to-income ratio of no more than 38 percent). After the goals came into force and especially as they were increased between 1996 and 2008, the GSEs found that they could not find a sufficient number of prime mortgages to meet the goals; there were simply not enough prime borrowers below median income. Accordingly, Fannie and Freddie gradually reduced their underwriting standards through the 1990s and into the 2000s in order to acquire nonprime loans and thus meet the affordable housing quotas. Reduced standards could not be limited to low-income borrowers. Even homebuyers who could have afforded prime mortgages were happy to take mortgages with much lower (or zero) down payments. By 2007, 37 percent of loans with down payments of 3 percent went to borrowers with incomes above the median. Thus the lower underwriting standards -- meant to assist low- or middle-income borrowers -- spread to the wider market. This produced the largest housing price bubble in modern history between 1997 and 2007, when it finally began to deflate, as shown in [the chart below]. It’s easy to see how lower underwriting standards can result in a housing bubble. If a potential buyer has saved $10,000 to buy a home and the underwriting standard requires a 10 percent down payment, he can buy a $100,000 home. But if the underwriting standard is reduced to 5 percent, he can buy a $200,000 home. Instead of borrowing $90,000, he borrows $190,000. This not only puts upward pressure on home prices, but also makes the borrower a weaker credit risk.

As lending standards weakened for everyone, home ownership among all races grew, but later contracted as borrowers defaulted on mortgages they could not afford to repay.

An academic paper by authors from MIT and the University of Chicago concluded that the Community Reinvestment Act led to risky lending, and at a Congressional hearing on the economic crisis in 2008, then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan confirmed that the crisis “essentially emerged out of the CRA [Community Reinvestment Act].”

The federal government subsequently appeared to be continuing to pursue the same risky mortgage policies. The Department of Housing and Urban Development issued a final rule that reiterated its support for prosecuting housing lenders for practices that have no discriminatory intent. And a comprehensive study of 2.4 million federally subsidized loans administered by the Federal Housing Administration in 2009-2010 found that 1 in 7 of those loans is expected to result in foreclosure among low- and middle-income families. The default rate for mortgages that received federal subsidies since 2009 was almost 50 percent.

While the allegation that the financial services sector was deregulated in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis was used to justify enacting new regulations, in fact financial regulation increased in the decade leading up to the financial crisis.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine how disparate impact claims created college credentialism.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9

Government broke the home mortgage industry with CRA, Freddie & Fannie, below market equilibrium interest rates and excessive business regulations that cause capital to pursue selfish real estate equity returns instead of more inclusive returns from starting and growing a small business… which can and should include building more housing units.

There is no question that these things led to the financial bubble that popped in 2008. However, many if not all of the things that caused the Great Recession meltdown are still in place today. The only thing saving us from another similar bubble and meltdown is that fewer mortgage lenders are participating in the feeding frenzy caused by government… even as they fight with the FDIC and other audit findings that they do not strongly comply with CRA requirements.

I am generally in favor of thoughtful and effective government programs that nudge private business to a particular public policy goal as long as the goal in focused on, and demonstrates results for, improving the human condition without causing significant harm. CRA is better now, and lenders are wiser about it… but it is still resulting in harm and needs significant reform.