“Disparate Impact” -- Part 5

The real causes of disparities among people grouped by race.

The influential New York Times bestselling author of “How to Be an Antiracist,” Ibram X. Kendi, says “When I see racial disparities, I see racism.” Indeed, the false assumption that racism explains all disparities among people grouped by race is the rationale behind disparate impact lawsuits generally. The problem is it’s simply incorrect to assume that a single cause explains a more complex problem. As the mathematician A.F.M. Smith wrote, “Any approach to scientific inference which seeks to legitimise an answer in response to complex uncertainty is, for me, a totalitarian parody of a would-be rational learning process.”

Ibram X. Kendi’s view of “anti-racism” is neatly summarized by Samuel Kronin as follows:

Kendi’s central intellectual contribution has been a redefinition of “racism” and how it works. As he argues in his most recent book How To Be An Anti-Racist, there is no such thing as being a “not-racist”—there is only anti-racism and racism. Indeed, simply claiming to not be racist is a form of denial, the very “heartbeat of racism.” For Kendi, “anti-racism” means supporting and instituting policies and ideas that level racial disparities of socio-economic outcome, while “racism” consists of any policy or idea that results in racial inequity.

For instance, if black Americans have less wealth than whites en masse, that disparity is prima facie evidence of racism under Kendi’s articulation—whether past or present, overt or subtle, conscious or unconscious, intentional or inadvertent—and the goal of “anti-racism” is to eliminate the gap. To argue that wealth disparities are rooted in cultural holding patterns or internal group factors, rather than discrimination per se, is ultimately to express a “racist” idea.

Moreover, while most Americans proceed from the assumption that racism is a form of prejudice that derives from either hatred or ignorance, Kendi posits that we have it totally backwards: in his view racist policy derives from majoritarian socioeconomic self-interest from which comes racist ideas to justify the unequal outcomes created by those policies, while ignorance and hatred are just the interpersonal fallout of racist policies and ideas.

In Kendi’s own words:

The opposite of “racist” isn’t “not-racist.” It is “anti-racist.” What’s the difference? One endorses either the idea of a racial hierarchy as a racist, or racial equality as an anti-racist. One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an anti-racist. One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an anti-racist. There is no in between safe space of “not racist.” The claim of “not racist” neutrality is a mask for racism.

Based on that false binary definition of racism, Kendi then applies it to policy in the following way:

A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups. An antiracist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial equity between racial groups. By policy, I mean written and unwritten laws, rules, procedures, processes, regulations, and guidelines that govern people. There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.

As Samuel Kronin continues:

It is this definitional shift of racism upwards—from a belief or an attitude that projects antipathy towards an identifiable Other to any explanation of a racial disparity that doesn’t explicitly name and blame “racist” policies and ideas—that is significant about his writing. This shift flows naturally from the underlying assumptions that disparities are always a consequence of racism. The principle of colorblindness is therefore not just wrong in Kendi’s and similar thought, but it is actually racist in this telling. Kendian logic insists that it is impossible to look beyond race, and the effort to do so can only be a guise for maintaining the “racist” status quo.

Moreover, discrimination by itself is not necessarily racist in this view, so long as it is used to create racial equity. Kendi explains thusly: “The only remedy to racist discrimination is anti-racist discrimination. The only remedy to past discimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

Although it may be off-putting to some, Kendi’s weird style of painting in broad strokes of morally binary black-and-whites before scrambling them around and repeating them backwards as though it somehow further qualifies his argument is clearly getting him somewhere. This framework represents the latest stage in the conceptual expansion of “racism” that has been gradually unfolding since the late 1960s.

Kendi’s popular yet false formulation of racism is politically useful to many activists today, because while instances of actual racism have declined dramatically since the 1960s, those activists needed to find new ways of labeling things “racist” in order to continue to justify their activist missions. Kendi even advocates for a Constitutional amendment to allow the government to require equal results, regardless of the causes of disparities in social science metrics. In “Stamped from the Beginning,” Kendi advocates that legislators “pass grander legislation that re-envisions American race relations by fundamentally assuming that discrimination is behind the racial disparities (and not what’s wrong with Black folk), and by creating an agency that aggressively investigates the disparities and punishes conscious and unconscious discriminators.” But as Nobel Prize-winner Friedrich von Hayek has said, “Making people equal [in outcome] a goal of governmental policy would force government to treat people very unequally indeed.” The United States Supreme Court has held as much itself, which, based on empirical evidence, has rejected the idea that statistical disparities are proof of discrimination. As Hans Bader points out: “In a 6-to-3 ruling, the Supreme Court [in the 1989 case of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.] said that it is “completely unrealistic” to think that in the absence of racism, minorities will be represented in a field “in lockstep proportion to their representation in the local population.” Along the same lines, in an 8-to-1 ruling in the 1996 case of United States v. Armstrong, the Supreme Court emphasized that there is no legal “presumption that people of all races commit all types of crimes” at the same rate, since such a presumption is “contradicted by” real world data showing big differences in crime rates, and held racial disparities in arrest or incarceration rates don’t violate the Constitution’s ban on racial discrimination. Because recognizing the fact that disparities among people grouped by race cannot justifiably be assumed to be the result of racism is already constitutional law, Kendi and his followers find themselves having to advocate for amending the Constitution to allow government to do just that.

In fact, there are many obvious causes of disparities among any set of people grouped by race that have nothing to do with racism, and such disparities are statistically inevitable. In the first post I put up on The Big Picture, I linked to a video I made that explains some of the key factors in understanding how relatively small statistical differences in behaviors among people grouped by race can result in disparities. You can watch the video here (the part explaining disparities starts at the 1:15 minute mark). I introduced the topic like this:

As Thomas Sowell points out in his book Discrimination and Disparities, it’s statistically inevitable that when you group people together in different ways, including by race, those groups aren’t going to have equal outcomes as a group. For example, if you need to meet three criteria to achieve a certain outcome, and your chances of meeting all three of those criteria are 2/3 (or 66%), then your chance of achieving that outcome is 2/3 times 2/3 times 2/3, which equals to 8/27. But say one group – for reasons having nothing to do with racism -- has only a one-third chance of meeting one of those criteria instead of two-thirds. Then that group’s chance of achieving a given outcome would be 1/3 times 2/3 times 2/3, which equals 4/27. That’s half the odds of achieving the outcome simply because the odds of meeting one of the criteria dropped from 2/3 to 1/3. As Thomas Sowell explains, “What does this little exercise in arithmetic mean in the real world? One conclusion is that we should not expect success to be evenly or randomly distributed among individuals, groups, institutions or nations in endeavors with multiple prerequisites.” Now, to take a simple example, a child is better off when there are two loving parents in the house instead of one. When there are two loving parents in the home, kids get twice the supervision, twice the education, and often twice the resources. If there are just small differences regarding the presence of two loving parents in a home when you compare any groups based on race (or anything else), you’re going to get some differences – some disparities – among those groups.

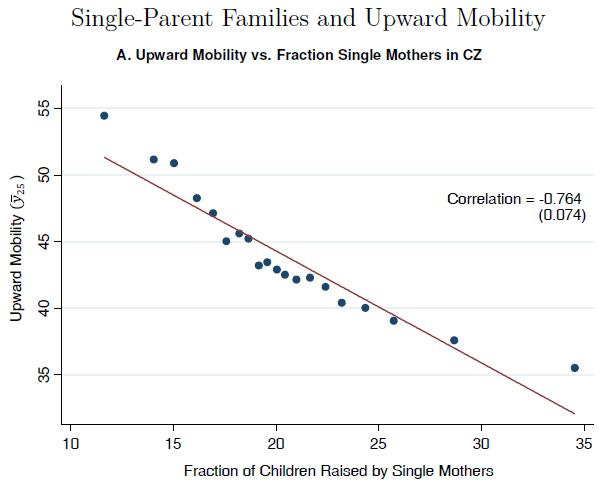

A large research project involving a study of over 40 million children and their parents found that the fraction of children living in single-parent households is the strongest indicator of less upward income mobility among all the variables explored. The researchers concluded that “family structure correlates with upward mobility not just at the individual level but also at the community level, perhaps because the stability of the social environment affects children’s outcomes more broadly.”

Harvard professor Orlando Patterson edited a book titled “The Cultural Matrix: Understanding Black Youth,” which included a chapter titled “More Than Just Black: Cultural Perils and Opportunities in Inner-City Neighborhoods,” by researcher Van C. Tran of Columbia University, who examined cultural differences between West Indian second-generation young people and native black young people in New York City to determine what might explain the greater success of those West Indian second-generation young people. As Tran writes:

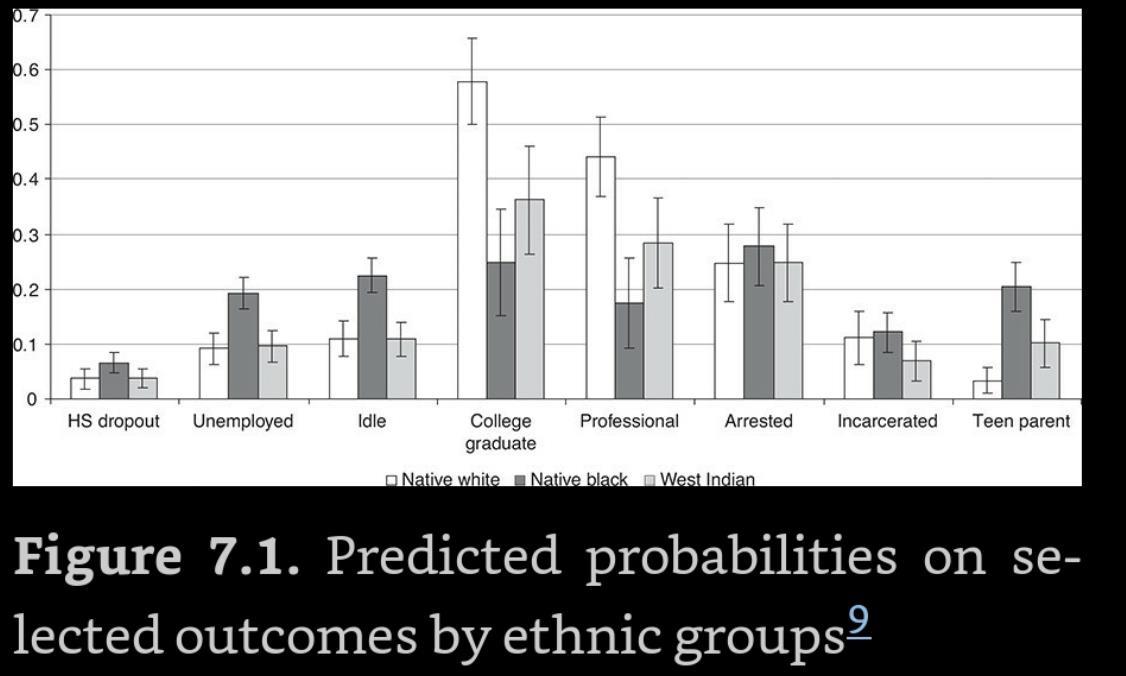

[T]here has been a dearth of research examining the neighborhood experiences of second-generation West Indians who grew up in similar neighborhoods and often live in close proximity to native blacks … I will compare and contrast the experience of second-generation West Indians to that of native blacks … By examining two different ethnic groups in a similar structural context, this chapter contributes to the ongoing debate on the relative importance of ethnic culture and social structure in shaping one’s life chances … I also document the different ways in which second-generation West Indians and native blacks navigate their neighborhood environments, with the former reporting stricter parenting … [B]y comparing two culturally distinct groups living in similar types of neighborhoods, this analysis reveals the relative importance of ethnic culture and social structure in shaping life chances … In their daily life, [West Indian second-generation youth] are also as likely as blacks to experience discrimination and prejudice from native whites and others, because internal ethnic distinctions among blacks often elude many native whites. The sociologist Mary Waters referred to this as “the invisibility of the Caribbean immigrants as immigrants and their visibility as blacks.” … This chapter builds on this debate by comparing the experience of second-generation West Indians with native blacks, essentially avoiding immigrant selectivity among the first generation as a likely explanation for differences in socioeconomic outcomes … Overall, data from the ISGMNY study confirm the second-generation advantage among West Indians across eight measures: high school dropout, unemployment rate, NEET6 rate, college graduate, professional attainment, arrest rate, incarceration rate, and teenage pregnancy. These eight measures are standard outcomes in urban poverty research, providing a comprehensive snapshot of socioeconomic attainment. Native blacks reported the most disadvantaged outcomes, while West Indians reported outcomes similar to those of native whites. For example, 11.4 percent of the native black sample did not have a high school education, compared to only 6.9 percent of West Indians and 4.2 percent of native whites. Native blacks were twice as likely to be unemployed compared to West Indians (11.8 percent) and native whites (9.1 percent). Similarly, their NEET rate (25.7 percent) was twice higher than West Indians’ (13 percent) and four times the rate of native whites (6.3 percent) … Among native black females, the teen pregnancy rate (24.7 percent) was also double West Indians’ (12.7 percent) and six times higher than native whites’ (3.5 percent). Among native black males, the arrest rate was 31.9 percent and the incarceration rate was 15.7 percent, higher than those for West Indians and native whites … Moving beyond descriptive statistics, Figure 7.1 presents selected predicted probabilities for eight outcomes for all three ethnic groups based on multivariate logistic regression analyses that include controls for key demographics and family background.

Controlling for observed background conditions, West Indians are much less likely than native blacks to drop out of high school, be unemployed, be idle, or have a child by the age of eighteen. They are also much more likely than native blacks to have graduated from college and to be in a professional occupation by the age of twenty-five. However, there are no significant differences between native blacks and West Indians (or native whites) in arrest and incarceration rates. These results indicate a clear West Indian advantage in educational and labor market outcomes, even after controlling for parental background characteristics (i.e., measurable characteristics in immigrant selectivity) … To begin, Figure 7.2 provides bivariate results on neighborhood trajectories over time using share of non-Hispanic whites and mean household income at the census tract level for West Indians, native blacks, and native whites … The previous section documented that native blacks and West Indians grew up in structurally similar, yet not identical, neighborhoods … Specifically, I point to three cultural mechanisms that partially explain the attainment gap between West Indians and native blacks: parenting strategies, involvement with the local drug trade, and the neighborhood peer networks … Another key difference was family structure. West Indians also grew up with more adult figures in the household because they were more likely to grow up in two-parent households and their household tended to include both kin and non-kin adults. In contrast, native blacks were more likely to grow up in single-parent households where the father was absent and the mother bore the burden of parenting, disciplining, and supervision. Specifically, 34 percent of native black respondents reported growing up with a single mother, compared to 25.6 percent of West Indians. This closer supervision has several implications for delinquency among the second generation, from drug use to skipping school … Many second-generation respondents recalled closely supervised visits to the neighborhood playground during childhood, hours spent at the local museum or library, and stricter curfew times during adolescence. When they went outside to play, they “could just be in front of the house” and “couldn’t go to too many places” because their parents were afraid to let them out of sight. For example, Sheena, a thirty-one-year-old West Indian female, described her mother’s decision not to allow her to play outside as a “typical kind of West Indian immigrant thing” because her mother did not want her to “mix with the Americans and all that foolishness.” … Another key difference was family structure. West Indians also grew up with more adult figures in the household because they were more likely to grow up in two-parent households and their household tended to include both kin and non-kin adults. In contrast, native blacks were more likely to grow up in single-parent households where the father was absent and the mother bore the burden of parenting, disciplining, and supervision. Specifically, 34 percent of native black respondents reported growing up with a single mother, compared to 25.6 percent of West Indians. This closer supervision has several implications for delinquency among the second generation, from drug use to skipping school … The role of family support in sheltering and protecting their children is repeatedly emphasized by West Indians. In sum, there is a combination of cultural strategies that promote social mobility: strict and protective parenting; a supportive home environment; and spending time inside doing homework and distancing from the street life in poor neighborhoods. These cultural strategies are neither specific to a particular ethnic group nor to a particular social class, though the qualitative data presented here suggest they were more prevalent among West Indians than native blacks … More broadly, these findings suggest that race is “more than just black” and the complex link between ethnicity and culture deserves further research.

Other researchers have found that Black immigrants’ earnings have largely closed the gap with white earnings, whereas there are continued earnings gaps between native blacks and whites, due in significant part to the poor education provided to many low-income black students from single parent families in America. As the researchers write:

We provide new evidence on earnings gaps between non-Hispanic White and three generations of Black workers in the United States during 1995-2024, using nationally representative data. Results reveal remarkable earnings advances among 2nd-generation Black immigrants, opposite to the well-documented widening in overall Black-White earnings gap. Among women, 2nd-generation Black workers have earnings higher than or equal to White women; among men, they earn 10% less at the median, but the gap vanishes at the top decile … The native Black-White gap remains stubbornly high. Educational attainment largely drives 2nd-generation success … These findings provide critical data to set the record straight on the accomplishments of the highly successful and rising demography of Black immigrants and their US-born children.

Similarly, regarding disparities within the black community, in 2021 an 11-member government commission in England (whose chairman is black, and consists of only one white member), found in its report that single-parent households were a prime driver of disparities in England. As the Wall Street Journal reported:

Black Caribbean children perform worse in British schools than those of any other group. “For years,” [Commissioner] Sewell says, “it has been said that this is explained in terms of teachers’ racism.” Yet black African students —“same age, same demographic, same classroom”—had academic achievement rates higher than those of whites. In fact, he says, all ethnic groups other than Caribbean blacks perform better than white British students, with the exception of Pakistanis, who are on par with whites ... While 14.7% of all British families are single-parent units, the share is 63% in the black Caribbean community.

We’ll continue this discussion in the next essay.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9