“Disparate Impact” – Part 3

How disparate impact claims created college credentialism.

Certain types of lawsuits based on statutes and regulations promoting disparate impact claims have also distorted the incentives for potential employees and potential employers and created college “credentialism” in which there are increased demands for college degrees that don’t reflect any learning that might actually be necessary for a given job obtained after graduation.

Employers used to use more of their own internal exams to judge whether or not a person had the aptitude to be hired right out of high school. But in 1971, the Supreme Court held, in a case called Griggs v. Duke Power Company, that employers could be held liable under the civil rights laws for applying employment tests that were “neutral on their face, and even neutral in terms of intent” if they resulted in the hiring of what was determined to be too few people in certain protected categories, including minorities.

Since research shows that most legitimate job selection tests will routinely trigger liability under such a “disparate impact” rule, such tests are little used today to select employees right out of high school.

In 1975, Nathan Glazer wrote in the book Affirmative Discrimination: Ethnic Inequality and Public Privacy, that the federal Civil Service Commission eliminated arithmetic and algebra from its exam after the exam was accused by the federal Civil Rights Commission of eliminating too many protected classes from job eligibility:

As Donald Devine writes:

Forty-four years ago, as Reagan’s successful political team was transitioning into office, we were advised that elements of the outgoing Carter administration had settled with civil rights groups to end Professional and Administrative Examination (PACE) intelligence tests. These had long been required for entry into top government positions to ensure a fair selection of applicants for an objectively tested civil service. The justification for the change was that the tests were “discriminatory” since white people scored higher on the exams, suggesting that they were racially biased against black minority applicants … over the years, the government basically gave up trying to produce IQ-like tests that did not produce the same results. The lack of real examinations for top government employment is not widely known and clearly undermines the principles of the original Pendleton Act of 1883 and its extensions, all of which required that “recruiting, selecting, and advancing employees on the basis of their relative ability, knowledge, and skills, including open consideration of qualified applicants for initial appointment.” Over the years, the government began selecting top applicants primarily by “examinations,” where applicants assessed their own attributes and skills … With the great majority of applicants self-testing, obviously very few applicants failed when assessing themselves. So, bureaucrats, especially at higher levels, selected people they or their associates knew. In fact, the overwhelming number of mid-to-upper-level vacancies in the civil service have long been filled by what are called “name requests” (Direct Hiring Authority). This is a “semi-spoils system”—not of political pals as before nineteenth-century civil service reforms, but of bureaucratic friends and acquaintances.

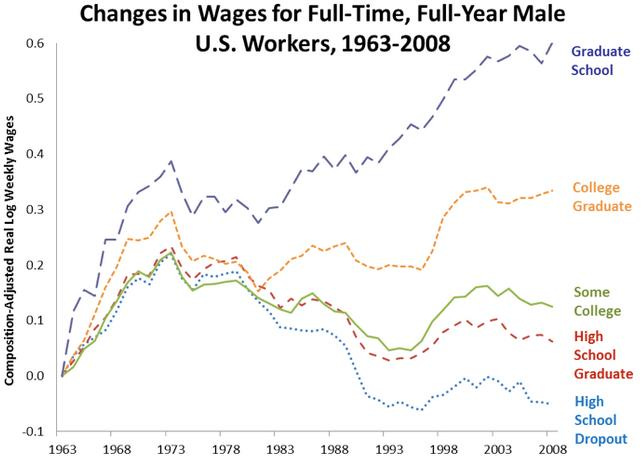

At about the same time, the effects of the Supreme Court decision prohibiting employment tests based on disparate impact became felt in the labor markets in the late 1970’s, when private employers increasingly abandoned reliance on their own internal employment tests and instead used a four-year college degree as a proxy, as evidenced by the rapid rise in the median income differential between those with high school and college degrees following the Supreme Court’s decision. The chart below shows how, starting in the late 1970’s, to obtain median incomes, both men and women usually needed a college degree they hadn’t needed previously.

Today, some 61% of employers have rejected applicants with the requisite skills and experience simply because they didn’t have a college degree, according to a 2017 Harvard Business School study. If current trends continue, the authors found, “as many as 6.2 million workers could be affected by degree inflation -- meaning their lack of a bachelor’s degree could preclude them from qualifying for the same job with another employer.”

As has been pointed out by Frederick Hess and Grant Addison:

Degree requirements are proliferating absent evidence they correlate with job necessity — and, indeed, despite some evidence to the contrary. A 2014 survey conducted by Burning Glass Technologies found that employers are increasingly requiring bachelor’s degrees for positions whose current workers don’t have one and where the requisite skills haven’t changed ... Ironically, indiscriminate degree requirements carry obvious disparate-impact implications, making their casual acceptance all the more remarkable. Indeed, the Harvard report noted that the practice disproportionately harms groups with low college graduation rates, particularly blacks and Hispanics.

Since the early 1980’s, the earnings gap between workers with a high school degree and those with a college education has become four times greater than the shift in income during the same period away from the bottom 99 percent. (Between 1979 and 2012, the gap in median annual earnings between households of high-school educated workers and households with college-educated ones expanded from $30,298 to $58,249, or by roughly $28,000. During the same period, 99 percent of households would have gained about $7,000 each, had they realized the amount of income that shifted during that time to the top 1 percent.)

At about the same time college credentialism significantly increased, young people began delaying getting married, as college degrees became practically required for most better-paying jobs.

The chart below contains more detailed wage differential information over time, also showing greater divergence since the late 1970’s.

In the next essay, we’ll look at yet more public policies that have become dysfunctional under the threat of lawsuits based on disparate impact claims.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9