Part 9 -- Antiracism as Memetic Virtue Signaling

A Critique of Kendi, DiAngelo, Hannah Jones, and Critical Race Theory

As was discussed in the last essay, the assumption that all disparities among people grouped by race are caused by racism is false, yet it propagates widely through various media. How? In part, the answer lies in an understanding of “memes.”

As James Gleick describes in his book “The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood,” geneticist Richard Dawkins explained the idea of a “meme” this way:

“I think that a new kind of replicator has recently emerged on this planet,” [Dawkins] proclaimed at the end of his first book, in 1976. “It is staring us in the face. It is still in its infancy, still drifting clumsily about in its primeval soup, but already it is achieving evolutionary change at a rate that leaves the old gene panting far behind.” That “soup” is human culture; the vector of transmission is language; and the spawning ground is the brain. For this bodiless replicator itself, Dawkins proposed a name. He called it the meme … “Memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation,” he wrote. They compete with one another for limited resources: brain time or bandwidth. They compete most of all for attention.

Memes survive and replicate in cultures that contain elements that increase its chances of survival. As Gleick continues:

Dawkins’s way of speaking was not meant to suggest that memes are conscious actors, only that they are entities with interests that can be furthered by natural selection. Their interests are not our interests. “A meme,” [Daniel] Dennett says, “is an information packet with attitude.” When we speak of fighting for a principle or dying for an idea, we may be more literal than we know. “To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble,” H. L. Mencken wrote. “But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true!” … [M]emetic success and genetic success are not the same. Memes can replicate with impressive virulence while leaving swaths of collateral damage — patent medicines and psychic surgery, astrology and satanism, racist myths, superstitions, and (a special case) computer viruses. In a way, these are the most interesting — the memes that thrive to their hosts’ detriment, such as the idea that suicide bombers will find their reward in heaven.

Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s stories are just the sort of meme that thrives to its host’s detriment, as their false narratives of “systemic racism” sap their alleged victims’ sense of agency (as was described in Part 7), while fueling a sense of virtue.

Gleick goes on to recount the history of chain letters:

[Chain letters] are memes; they have evolutionary histories. The very purpose of a chain letter is replication; whatever else a chain letter may say, it embodies one message: Copy me. One student of chain-letter evolution, Daniel W. VanArsdale, listed many variants, in chain letters and even earlier texts: “Make seven copies of it exactly as it is written” [1902]; “Copy this in full and send to nine friends” [1923] … Chain letters flourished with the help of a new nineteenth-century technology: “carbonic paper,” sandwiched between sheets of writing paper in stacks. Then carbon paper made a symbiotic partnership with another technology, the typewriter. Viral outbreaks of chain letters occurred all through the early twentieth century … Two subsequent technologies, when their use became widespread, provided orders-of-magnitude boosts in chain-letter fecundity: photocopying (c. 1950) and e-mail (c. 1995).

These chain letters replicated because they contained promises of rewards or punishments: pass this along to seven friends or bad luck will befall you, or some reward will result. Today, social media posts inviting people to read Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s books contain a similar invitation to repost. If the recipient doesn’t forward it along to friends, they risk looking “racist,” or they lose the opportunity to signal their own virtue, penalties or benefits that are entirely independent of facts or data. As Gleick analogizes, “Diets rise and fall in popularity, their very names becoming catchphrases -- the South Beach Diet and the Atkins Diet, the Scarsdale Diet, the Cookie Diet and the Drinking Man’s Diet all replicating according to a dynamic about which the science of nutrition has nothing to say.” In the same way, the Kendi and DiAngelo “anti-racism” diets spread according to a dynamic about which the social science of disparities has nothing to say.

The conditions making Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s false narratives ripe for replication include poor understandings of statistics and history, and consequently a poor understanding of the context statistics and history bring. Whereas there are myriad explanations for disparities in racial outcomes, Kendi posits only one: racism. Whereas disparities in racial outcomes are the result of the repeated tossing of dice that contain thousands of sides, each face of a different size, Kendi’s coin contains only one side, with allegedly infinite explanatory power.

Social media certainly seems to be awash in memes that have little explanatory power in the real world. For example, whereas a couple decades ago, many more blacks reported that discrimination rather than individual responsibility was the reason why many blacks don’t get ahead, more recent surveys indicated the opposite is true.

And as Eric Kaufmann points out, “whites and minorities in America largely agree on what is and isn’t racist. The only significant difference is over whether racial quotas in university admissions are racist, and, even here, a majority of both non-whites (57 percent) and whites (77 percent) say they are … whites and minorities place the racism/non-racism boundary in a similar place across a wide range of questions …” When asked “Do you think the following is racist?” the statement “Favoring own race for job” was considered racist by over 80% of both whites and blacks.

White liberals now have opinions on whether discrimination is a factor holding back black advancement that are much to the left of the opinions of blacks themselves. White liberals are to the left of black Democrats, with white Democrats placing a much stronger emphasis than blacks on the role of discrimination and much less emphasis on the importance of individual effort. Among white liberals, according to Pew survey data collected in 2017, 79% agreed that “racial discrimination is the main reason why many black people can’t get ahead these days.” 19% agreed that “blacks who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition.” Among blacks, 60% identified discrimination as the main deterrent to upward mobility for blacks, and 32% said blacks were responsible for their condition.

Even that 32% is a drop since 2015, when Harvard professor Orlando Patterson wrote the following in his book “The Cultural Matrix”:

When asked to evaluate the problems facing black men, 92 percent of black youth, aged eighteen to twenty-four, say that “young black men not taking their education seriously enough” is a “big problem,” while 88 percent say likewise for “not being responsible fathers.” … [B]lack youth are more likely than white youth to say that black men are to blame for their own problems … Asked whether or not they think the problems facing black men are more a result of what “white people have done to blacks” or more a result of what “black men have failed to do for themselves,” 16 percent of black youth cite the former, while 67 percent choose the latter (with 18 percent saying both factors are equal). In comparison, white youth are more likely to say the problems facing black men are due to what “white people have done to blacks” (31 percent), while 41 percent blame young black men, and 28 percent say both are equally important reasons … black youth also think that incarceration is, at least in part, due to the fact that black men are less likely to think committing crimes is wrong (43.4 percent) and that “many black parents aren’t teaching their children right from wrong” (57.4 percent) … [T]here will be no substantial change among the millions of disadvantaged youth and their families in the inner cities until black Americans assume full responsibility for the internal social and cultural changes that are essential for success in the broader mainstream capitalist society … We pointed out earlier that black youth are likely to agree with President Obama’s recent injunction to reject the view that circumstances beyond their control define them and their future.

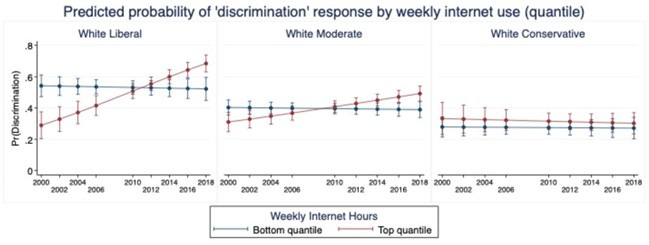

Could social media memes be to blame for some blacks’ more recent understanding that racism has somehow gotten much worse since Barack Obama was elected president? Zach Goldberg points out that “we also see that the predicted probability of a ‘discrim[ination]’ response from those placing in the bottom quantile of weekly internet use remains more or less flat across time, while the odds of this response from the top quantile shows a significant secular [long-term trend] increase.”

That is, the more one is exposed to social media memes, the more one attributes disparities to racism, compared to those who spend less time online (and more time in real life).

Also, changing views on the prevalence of discrimination can lead to changing views of the decreased moral value of individuals based on the color of their skin, a clear setback for civil rights. Interestingly, one experiment showed that political liberals were biased against saving the life of someone whose name sounded white. Researchers at Northwestern, Cornell, and the University of California conducted the following experiment, with the following results:

College students and community respondents were presented with variations on a traditional moral scenario that asked whether it was permissible to sacrifice one innocent man in order to save a greater number of people. Political liberals, but not relatively more conservative participants, were more likely to endorse consequentialism [killing one to save many] when the victim had a stereotypically White American name [Chip Ellsworth III] than when the victim had a stereotypically Black American name [Tyrone Payton].

Moving beyond hypotheticals posed by academics to college students, the next essay will examine recent real-world legal and policy applications of Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s race-based views.

Links to all essays in this series: Part1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

Collected essays in this series

Short video documentary on problems with popular critical race theory texts

Harvard Law School flashback