Part 4 -- Antiracist, Anti-Enlightenment

A Critique of Kendi, DiAngelo, Hannah Jones, and Critical Race Theory

Previous essays sought to explain how Robin DiAngelo’s and Ibram X. Kendi’s recent books (DiAngelo’s White Fragility and Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and How to Be an Antiracist) embrace some of the methods and the false moral certainty of the Malleus Maleficarum, the most popular guide to identifying and eradicating witches in the Middle Ages. This essay will explore the ramifications of their explicit rejection of both the humanist focus on the individual and the Enlightenment focus on objectivity and the scientific method, concepts that were instrumental in discrediting the medieval witch hunts, and other false beliefs.

Erasing the Individual to Better See Collective Guilt

In White Fragility, DiAngelo writes, “exploring [her preferred] cultural frameworks can be particularly challenging in Western culture precisely because of two key Western ideologies: individualism and objectivity.” She explicitly singles out the concepts of individualism and objectivity as barriers to understanding “cultural frameworks,” when such concepts are actually a means of facilitating understanding by analyzing the validity of competing assumptions with empirical methods.

DiAngelo believes individualism is a threatening aspect of “white identity,” writing in White Fragility that “a significant aspect of white identity is to see oneself as an individual, outside or innocent of race – ‘just human.’” The idea that people should be treated as “just human,” rather than as members of a racial caste, underpins the concept of “colorblindness,” which teaches people should be treated as individuals, not as members of a team wearing jerseys of the same skin color. But DiAngelo explicitly rejects the concept of colorblindness as somehow racist, stating “To challenge the ideologies of racism such as individualism and color blindness, we as white people must suspend our perception of ourselves as unique and/or outside race.” As Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay write in their book Cynical Theories, “The intense focus on identity categories and identity politics means that the individual [as a moral agent] and the universal [as a moral concept] are largely devalued.” In this way, DiAngelo and other practitioners of identity politics seek to bring society back to a pre-humanist, quasi-medieval era, which, as described by Pluckrose and Lindsay “seeks to establish a caste system based on Theorized states of oppression.”

The notion that society should be viewed as system of oppression among groups (rather than as a means of organizing unique individuals) is part of a movement called “postmodernism,” which devalues individual accomplishment in favor of social movements. I was recently reading Kurt Beyer’s Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age, a biography of pioneer computer programmer Grace Hopper, and was struck by its observation that “Postmodernism even led to disfavoring of biographies because it was thought the individual person didn’t really exist,” when in fact “Every institution, every organization, and every government is an aggregate of unique individuals, each with his or her own ‘personal society’ that is continuously refined and updated,” with Hopper being one of those unique individuals.

Postmodernism’s dismissal of individualism cuts directly against the grain of America’s philosophical foundation, which remains so appealing to immigrants from around the world. Roya Hakakian’s A Beginner's Guide to America: For the Immigrant and the Curious, is a guide to American norms for new immigrants. In it, Hakakian encapsulates the individualist morality that permeates American culture for those coming here:

You should learn sooner rather than later that “you” and “I” are America’s most celebrated pronouns. “He,” “she,” “it,” “we,” or “they” cannot begin to compete. In fact, “you” and “I” are among the most frequently used words in the English language. Schoolchildren are taught to avoid vague usages like the passive voice, or sentences whose subjects are obscure. However clumsily, they learn to boldly begin with “I” and forcefully state what the “I” sees, hears, feels, and believes in.

Kendi Thinks the Moral Principle of Colorblindness Is Really Some Sort of Physical Disability

Despite Kendi’s attacks on the moral principle of colorblindness, that moral principle continues to resonate with most people. In November, 2020, for example, even Californians voted down – by a large margin -- Proposition 16, which would have repealed this provision in their state constitution: “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.”

The concept of colorblindness, of course, aims to focus social interactions on individual character, not group identity. Consequently, Kendi seeks to discredit the prevailing concept of “colorblindness” at the individual and policy level. But “colorblindness” is such a compelling moral concept that Kendi must create a strawman to oppose it. The moral and legal concept of “colorblindness” of course has nothing to do with anyone’s willful blindness to the fact that people have different skin color. Rather, it’s a metaphor for a universal moral and legal principle that states even though people have different skin colors, they should be treated as if they had the same skin color, as skin color is irrelevant to an individual’s moral worth. As former slave and civil rights leader Frederick Douglass said, “color should not be a criterion of rights, neither should it be a standard of duty. The whole duty of a man, belongs alike to white and black,” and also “all distinctions, founded on complexion, ought to be repealed, repudiated, and forever abolished.”

In her prescient 2001 book Race Experts: How Racial Etiquette, Sensitivity Training, and New Age Therapy Hijacked the Civil Rights Revolution, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn writes:

It was precisely the moral objections … raised by Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders that resonated to a vast number of Americans and ensured drastic change. King appealed constantly to universal rights and dignity as well as unity and interdependence when he called on Americans “to make real the promises of democracy.” … His legendary words made the implications of this universalism concrete, comprehensible, and compelling: “I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” The unrelentingly moral logic that caused King to emphasize character, with its connotations of self-discipline and obligation to the common good, had everything to do with the movement’s success in attacking the brutal hypocrisy and racial double standards of segregation.

King’s was an ennobling vision, and the meaning of his celebration in America isn’t lost on Roya Hakakian, who writes in her guide for new immigrants A Beginner's Guide to America the following in a section on American holidays:

Then along comes January with Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. Note the word “birthday” as opposed to “death day.” Americans could have chosen to mark the dramatic day of Dr. King’s assassination. Somber crowds would have had every reason to march on the streets and shed tears over his martyrdom. Instead, they celebrate his birth. Schoolchildren put on their best to sing songs at their assemblies and remember his legacy. Everyone professes to “have a dream” on the third Monday in January, even those who may prefer to forget the man and his cause. In the battle between joy or gloom, you can always count on Americans to choose the former.

Now contrast the uplifting moral principle of colorblindness to Kendi’s reducing it to a physical disability. In How to Be an Antiracist, Kendi somehow finds his way to counter-factually claiming that proponents of a “colorblind” moral and legal principle are actually denying the physical reality of different skin colors in order to discredit the moral principle of colorblindness. Kendi writes, “the color-blind individual, by ostensibly failing to see race, fails to see racism and falls into racist passivity. The language of color blindness -- like the language of ‘not racist’ -- is a mask to hide racism.” Kendi repeats his mischaracterization of the concept of moral and legal “colorblindness” in his children’s book Antiracist Baby, which states “If you claim to be color-blind, you deny what’s right in front of you” next to an illustration of people with different skin colors. Again, colorblindness as physical disability. (Ironically, the same book (Antiracist Baby) ends with the seemingly contradictory line “Antiracist baby … doesn’t judge a book by its cover.” When I read that I thought, “If one can be ‘cover-blind’ as a matter of principle, why can’t one be colorblind as a matter of principle?”

Kendi even maintains “The most threatening racist movement is not the alt right’s unlikely drive for a White ethnostate but the regular American’s drive for a ‘race-neutral’ one.” In Kendi’s perverse view, celebrating Martin Luther King Jr’s colorblind vision for America is a more threatening concept than white supremacy. How to explain the appeal of this perverse view among many of America’s elites? It starts with understanding that it is Kendi’s view, not “the regular American’s drive for ‘race-neutrality,” that is rooted in racist appeal. As Andrew Sullivan said recently in an interview, Kendi and DiAngelo’s new form of racism appeals to the very same tribal sense to which older forms of racism appeal:

[Wokeness is] also much more conducive to human nature to see people in terms of groups rather than individuals … We are essentially tribal. And so what wokeness appeals to, in the way that the far right also appeals, it appeals to tribalism, and tribalism in its crudest sense of being able to identify people instantly as a member of your tribe or another tribe … So of course it’s likely to be more successful when you combine it with a form of moral rightousness as well. To tell people you can be tribalists and moral at the same time is an incredibly attractive way of life. To be able to see a white male and know instantly that person is part of the problem, before you even talk to them, is hugely rewarding … Liberalism, the achievement of seeing the individual independently of his or her group, is hard. It’s counter-intuitive, and so it’s always on the defensive in many ways. And whether it’s a sort of tribal right-wing racism or whether it’s a tribal left-wing neo-racism, they both come more naturally to humans than liberal discipline.

Twenty years ago, Lasch-Quinn also remarked on the shared roots of racism and “racial identity theory,” writing in Race Experts:

The civil rights movement did bring a revolution to American life, but the forces of reaction – though often striking a liberal or radical pose – gave a new lease on life to race-conscious behavior not entirely unlike the double racial standard that ruled under white supremacy. Racial identity theory, oppression pedagogy, interracial etiquette, ethnotherapy – these are only a few examples of the new ministrations of the self-appointed liberation experts. That we have allowed the civil rights revolution to be hijacked by these social engineers is one of our best-kept secrets and one of our greatest tragedies.

That racial identity proponents have hijacked the civil rights movement is no longer a secret; today, they’re best-selling authors.

Kendi Rejects “Blinding” to Color and Promotes Binding to Color

At least the medieval witch hunts tended to unjustly punish individuals. Kendi and DiAngelo subject a whole category of people to collective assumed guilt, based on race. Indeed, Kendi must reject judging people as individuals because he explicitly supports punishing people as a group.

Again, in Kendi’s view, all disparities among people grouped by race are assumed to be due to “systemic” discrimination at the policy level as long as any disparities among people grouped by race are allowed to remain. As Kendi writes in How to Be an Antiracist (emphasis mine), “A racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity between racial groups,” and “There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.” In Kendi’s view, enforcing statistically equal outcomes to address disparities between people grouped by race will require discrimination based on race. As Kendi writes, “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

“If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist.” Did you get that? According to Kendi, when you actively discriminate against people based on the color of their skin, that’s somehow antiracist. Perhaps Kendi’s sequel to How to Be an Antiracist will be How to Be Antilinguistics. Thomas Sowell, writing in the early 1980’s in his book The Economics and Politics of Race, states “The question is not about the right or best definition of the word racism. Words are servants, not masters. The real problem is to avoid shifting definitions that play havoc with reasoning.” Under Kendi’s formulations, “anti-racism” is racist and “equity” is unfair. As Sowell has written, “If you have always believed that everyone should be judged by the same rules and be judged by the same standards, that would have gotten you labeled a radical 50 years ago, a liberal 25 years ago and a racist today.”

Antiracists, as Kendi views them, should support systemic racism themselves -- only a racism aimed in another direction. Further, according to Kendi, this official policy of racial discrimination should be enshrined in a constitutional amendment. As Kendi wrote in Politico:

To fix the original sin of racism, Americans should pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principals [sic]: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals. The amendment would make unconstitutional racial inequity over a certain threshold ...

Now, Karl Marx popularized a phrase to express the goal that would apply in a mythical socialist state: “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” Kendi’s modern reformulation appears to be “from each according to their ability, to each according to their race.” And according to Kendi, all departures from that maxim are tantamount to racism. As Kendi writes: “The opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘antiracist.’ What’s the difference? … One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist.” (And by “allowing racial inequities to persevere, Kendi means failing to enact policies that guarantee equality of results on a racial basis, even when differences in results are not caused by racism.)

Such racial reformulations of Marx’s maxim are not likely to bode well in an increasingly diverse America. Research shows that as Americans live among more racially and ethnically diverse people, the more they tend to value individualism over tribalism, as interethnic contact involves weakened in-group boundaries. For example, researchers recently reported:

In three studies, across different levels of measurement and analysis, we find converging evidence that ethnic diversity accompanies individualistic relational structures and increases the endorsement of individualistic values [such as the importance of the self being a separate and unique individual and the importance of self-achievement] … [F]uture increases in ethnic diversity will likely be accompanied by an increasing societal emphasis on individualistic dimensions -- for example, individual autonomy and a greater preference for uniqueness.

It would appear that, as America becomes more diverse, its people see more clearly the worth of unique individuals among that human diversity. Kendi, on the other hand, sees nothing but black and white.

And you can miss a lot of detail when you only see black and white. What happens when those in charge, and other elites, place undue emphasis on disparities regarding one race, and thereby lose sight of other disparities, worsening those other disparaties as a result? As Nicholas Eberstadt at the American Enterprise Institute explains:

Consider the saga of “deaths of despair” in modern America. In the late 1990s, America’s white working class was suddenly seized by a terrible health crisis. Among non-Hispanic white men and women of working age with no more than a high-school education, death rates commenced a gruesome rise. Between 1999 and 2015, mortality rates for these less educated Anglos jumped in every age group between 25 and 64 — and the spikes were practically Soviet in magnitude and nature. For men and women in their late fifties, death rates ratcheted up by 22 percent; they leapt by almost 90 percent for those in their early thirties. Across all these age groups, increased death rates from drug overdoses (“poisonings”), cirrhosis of the liver, and suicide contributed substantially to the carnage … The impact of the health crisis was nationwide, and its toll was horrendous. Between 1999 and 2015, excess mortality from rising death rates cost white working-class America hundreds of thousands of lives. Indeed, rough calculations suggest that this crisis may have exacted a cumulative total of over a third of a million premature deaths during that period alone (and it has continued since then). Yet the crisis went overlooked and undetected, year after year.

And what if an undue emphasis on race reduced people’s sympathy for others based solely on race? Researchers have also found that

White privilege lessons are sometimes used to increase awareness of racism. However, little research has investigated the consequences of these lessons. Across 2 studies, we hypothesized that White privilege lessons may both highlight structural privilege based on race, and simultaneously decrease sympathy for other challenges some White people endure (e.g., poverty)—especially among social liberals who may be particularly receptive to structural explanations of inequality. Indeed, both studies revealed that while social liberals were overall more sympathetic to poor people than social conservatives, reading about White privilege decreased their sympathy for a poor White (vs. Black) person. Moreover, these shifts in sympathy were associated with greater punishment/blame and fewer external attributions for a poor White person’s plight.

That is, an undue focus on race, not surprisingly, seems to actually reduce people’s ability to apply what should be universal fairness principles to everyone in a race-neutral way.

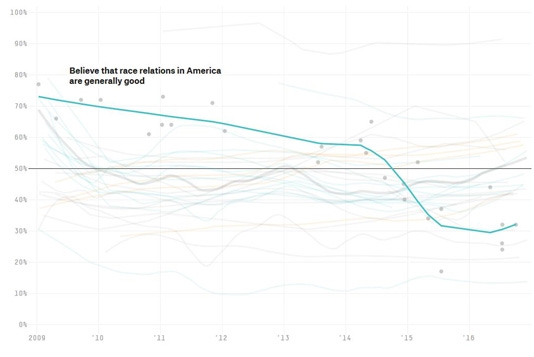

Indeed, regarding race relations, following the election of President Obama, and the renewed emphasis on race in federal policies, the state of race relations between whites and blacks got significantly worse.

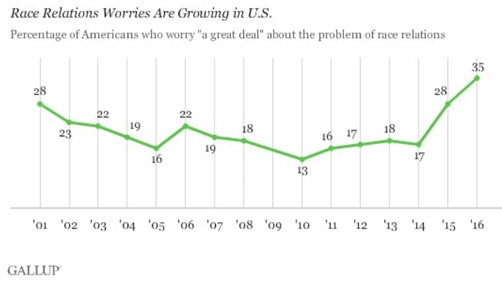

Worries about race relations hit record highs in 2016.

A summary of polling trends on race relations under the Obama Administration can be found here.

A January, 2020, Gallup survey on satisfaction reports that race relations and the “position” of minorities under President Trump were much higher than they were under President Obama. Race relations scored the highest satisfaction advance, 14 points, from 22% at the end of the Obama administration to 36% in January, 2020. And “The position of blacks and other racial minorities in the nation” jumped 9 points, from 37% in January 2017 to 46% now (January 2020).

In the next essay, I’ll explore how Kendi and DiAngelo, in order to heighten racial conscience, reject the very basis of science.

Links to all essays in this series: Part1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

Collected essays in this series

Short video documentary on problems with popular critical race theory texts

Harvard Law School flashback