Part 6 -- The Polluted Roots of The 1619 Project

A Critique of Kendi, DiAngelo, Hannah Jones, and Critical Race Theory

In this essay, I’ll discuss the New York Times’ “1619 Project,” a collection of articles claiming to introduce readers to a new way of thinking about American history.

The essays that compose the 1619 Project would have you believe that even today, the vestiges of slavery are everywhere. As Coleman Hughes has written, in the essay compilation Red, White, and Black: Rescuing American History from Revisionists and Race Hustlers, “Instead of teaching black children lessons they can use to improve their lives … the 1619 Project seems hell-bent on teaching them to see slavery everywhere: in traffic jams, in sugary foods, and, most surprisingly, in Excel spreadsheets.” Mr. Hughes is referring to Matthew Desmond’s 1619 Project essay, in which Desmond actually writes “When a mid-level manager spends an afternoon filling in rows and columns on an Excel spreadsheet, they are repeating business procedures whose roots twist back to slave-labor camps.”

Here’s how the New York Times introduced the 1619 in August, 2019. The Times stated “The 1619 Project … aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding …” because black servants were first brought to North American shores in that year. Here’s Nikole Hannah Jones, who heads the 1619 Project, reiterating that claim. She wrote “I argue that 1619 is our true founding” and “we are talking the founding of America. And that is 1619.”

If it were to make any sense to claim slavery is essential to the understanding of the founding principles of America as a separate nation, then there would have to be something about slavery unique to America at the country’s founding. But slavery was a worldwide phenomenon for thousands of years, and it still exists in parts of the world. Even the Western birthplace of democracy, ancient Athens, was based on a slave economy. As Robert Garland writes in his Great Courses lecture series The Other Side of History: Daily Life in the Ancient World:

We don’t know when, where, or under what circumstances human beings first reached the terrible decision that it was acceptable to reduce other human beings to slavery. It certainly wasn’t the Greeks who invented slavery—we know it was established in earlier cultures—but the Greeks, being a highly articulate and literate people, have provided a full record of how slavery functioned in their world. When we think of Greece’s great cultural accomplishments, we should never forget the unpalatable fact that these were supported by, if not based on, slavery—on the other side of history. Slavery in the Ancient Greek World. Slavery existed in Greece in the Mycenaean period from around 1600 B.C. onward. By the end of the 8th century B.C., at the very latest, slavery was so much a part of everyday life that even those who were poor owned slaves.

Human slavery is a supreme evil. It was also everywhere. This map shows the volume of slaves sold by African slave traders worldwide, with the width of the line indicating the relative volume of the sales. Much larger numbers of black slaves were sold by African warlords to slaveowners in the Middle East, and South America. Now, that everyone was doing it doesn’t excuse in the least the supreme horrors of slavery -- but it does put the lie to the false narrative that slavery uniquely defines America’s identity.

And slavery wasn’t a strictly white versus black phenomenon. The source of the slave trade -- without which it wouldn’t have existed as it did -- was overwhelmingly black African warlords, who enslaved other Africans for sale and profit. As Peter Lovejoy writes in “Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa”:

Slavery has been an important phenomenon throughout history. It has been found in many places, from classical antiquity to very recent times. Africa has been intimately connected with this history, both as a major source of slaves for ancient civilizations, the Islamic world, India, and the Americas, and as one of the principal areas where slavery was common. Indeed, in Africa slavery lasted well into the twentieth century – notably longer than in the Americas.

As Wilfred Reilly writes:

By almost every metric, the Arab slave trade was larger in scale than the white-dominated Atlantic slave trade. The well-regarded Senegalese scholar Tidiane N’Diaye has argued that at least 17 million Africans were sold into Arab slavery, with 8 million or so shipped from Eastern Africa to the Islamic world “via the Trans-Saharan route to Morocco or Egypt,” and 9 million more “deported to regions on the Red Sea or the Indian Ocean”—then both largely Arab lakes.* And while it is difficult and a bit tasteless to compare these things, the Arab trade was by all accounts as brutal or more so than its Western counterpart. The best academic research on point has concluded that “about three out of four slaves died” before ever reaching their destination and being sold into bondage, from causes including starvation, sickness, and plain “exhaustion after long journeys.” It was also longer-lasting than Western slavery, with slavery not being (formally) banned in the fairly typical Arab port of Zanzibar until 1873 and not abolished across Muslim East Africa until 1909 … Some Arab and Afro-Asiatic slave traders—almost all of whom, obviously, would have been Black or Muslim “people of color”—achieved legendary status during their eras and are remembered today. Probably most notable among these merchants of life was Hamad ibn Muhammad ibn Jum‘ah ibn Rajab ibn Muhammad ibn Sa‘īd al Murjabī—better known as Tippu Tip. A Black man himself, in any normal sense of that term, Tip was also the most powerful and widely known slave trader in Africa for most of the period between his birth in 1832 and death in 1905, supplying much of the world with Black slaves. [A video chronicling Tippu Tip’s life can be found here.] … There was in fact—for centuries—a regional slave trade focused entirely on the sale of white battle captives to Arab and Black Muslim masters: the Barbary slave trade. Ohio State’s Robert Davis estimates that Muslim “Barbary” raiders from the North African coast enslaved “about 850,000 captives over the century from 1580 to 1680,” and “easily” as many as 1.25 million between 1530 and 1780 … Using imperial Turkish customs records, another source—the Cambridge World History of Slavery—estimates that between two and three million mostly European slaves were shipped into the Ottoman Empire from the Black Sea region alone between the mid-1400s and the start of the eighteenth century. In this context, it is hard to avoid agreeing with Davis that—for whatever reason—many historians today “minimize the impact of Barbary slaving ... [and] the scope of corsair piracy.” Barbary slavers were famously ruthless and daring—launching military-scale raids on European cities on more than one occasion. In 1544, the legendary Caucasian Muslim Hayreddin Barbarossa (“the Red Beard”) captured both the sizable island town of Ischia and the city of Lipari, enslaving approximately 1,500 Christian Europeans in the first strike and between 2,000 and 3,000 in the second.28 Just seven years later, in 1551, another Muslim raider—Dragut or “Turgut Reis”—conquered the island of Gozo and sold the entire population as slaves: shipping 5,000 to 6,000 Europeans into the Ottoman Empire as chattels … Amazingly—to someone raised on modern curricula—totals from the Barbary era represent only a small percentage of those white Europeans enslaved by Muslim or African oppressors throughout history. Even leaving racially diverse Rome and her hordes of unfree people and the million-plus western European victims of Barbary raiders aside, the very word “slave” derives from “Slav”—the ethnic demonym for proud but historically “backward” whites occupying eastern Europe, millions of whom were sold into bondage over the centuries by Muslims and others. Across the sweep of time, from Athens to Istanbul, it is far from impossible that more whites than Blacks have been enslaved.

As David S. Landes describes in his book “The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor”, slavery dominated African commerce because conditions in Africa made using animals for work practically impossible: In Africa:

the vector is the tsetse fly, a nasty little insect that would dry up and die without frequent sucks of mammal blood. Even today, with powerful drugs available, the density of these insects makes large areas of tropical Africa uninhabitable by cattle and hostile to humans. In the past, before the advent of scientific tropical medicine and pharmacology, the entire economy was distorted by this scourge: animal husbandry and transport were impossible; only goods of high value and low volume could be moved, and then only by human porters. Needless to say, volunteers for this work were not forthcoming. The solution was found in slavery, its own kind of habit-forming plague, exposing much of the continent to unending raids and insecurity.

What slaves African warlords didn’t use themselves, they sold to others for profit. As described in Lovejoy’s Transformations in Slavery, interpretations of Islam that justified the enslavement of infidels accelerated the enslavement of Africans, and Africa became the source of slaves for the transatlantic slave trade to the Americas, the Middle East, and elsewhere around the world. As described by historian James Walvin in his book A Short History of Slavery, “The Islamic tradition of enslavement … meant that, in the very years when slavery was in sharp decline elsewhere in Europe, slavery was confirmed as an unquestioned feature of Iberian life,” which ultimately made its way to the Caribbean and South America following the discoveries of Christopher Columbus on behalf of Spain. Walvin continues, “In time, it came to be assumed that black Africans were natural slaves, though this had not been the case initially ... Arabs/Muslims began to think of black Africans as ideally suited for slavery. Gradually, a distinct racial prejudice emerged.”

As James Sweet has chronicled in “The Iberian Roots of American Racist Thought,” the racism that came to characterize American slavery derives in part from the cultural and religious history of Islam, as Islamic attitudes about blacks and slavery spread to Spain, Europe generally, and then America. He continues:

By the fifteenth century, many Iberian Christians had internalized the racist attitudes of the Muslims and were applying them to the increasing flow of African slaves to their part of the world ... Iberian racism was a necessary precondition for the system of human bondage that would develop in the Americas during the sixteenth century and beyond.

As Bernard Lewis has further described in his book Race and Slavery in the Middle East, “Inevitably, the large-scale importation of African slaves influenced Arab (and therefore Muslim) attitudes to the peoples of darker skin whom most Arabs and Muslims encountered only in this way [as slaves].” And as historian David Brion Davis explains in his book Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World:

The Arabs and other Muslim converts were the first people to make use of literally millions of blacks from sub-Saharan Africa and to begin associating black Africans with the lowliest forms of bondage … racial stereotypes were transmitted, along with black slavery itself.

Ibram X. Kendi also misleads regarding this history, in a way that perpetuates a false narrative that slavery was a racially binary practice, by implying that an English travel writer was the original source of a Biblical justification for black inferiority. Kendi writes in How to Be an Antiracist:

In 1578, English travel writer George Best … justified expanding European enslavement of African people. God willed that Ham’s son and “all his posteritie after him should be so blacke and loathsome,” Best writes, “that it might remain a spectacle of disobedience to all the worlde.”

But the use of the Biblical “descendants of Ham” story to justify enslaving black Africans far predated George Best. As James Sweet writes in “The Iberian Roots of American Racist Thought”:

Islamic interpretations of Noah's curse varied, but a tenth-century Persian historian, Tabari, presented a typically racial response. In what is considered the major Arabic historical work of the period, Tabari wrote: “Ham begot all blacks and people with crinkly hair. Yafit [Japheth] all who have broad faces and small eyes (that is, the Turkic peoples) and Sam [also called ‘Shem’ or ‘Sem,’ the mythical ancestor of the ‘Semites’] all who have beautiful faces and beautiful hair (that is, the Arabs and Persians); Noah put a curse on Ham, according to which the hair of his descendants would not extend over their ears and they would be enslaved wherever they were encountered.”

Slavery in Africa also continued long after it was abolished in the Americas. As Walvin writes:

By 1888, slavery had been swept away across the Americas. The same could not be said for Africa, however. Indeed, at the very point when Americans shed their appetite for black slaves, there may have been more slaves in Africa than ever before, more even than had been shipped across the Atlantic in the entire history of Atlantic slavery.

Researcher Zora Neale Hurston interviewed Cudjo Lewis, one of the last African slaves brought to America (illegally) in 1860. Cudjo Lewis’s own description of his enslavement in Africa by a competing black African tribe is recounted in Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” written in 1927. At the time, there was a popular myth that black slaves from Africa were lured into capture by white slave traders, when in fact they were overwhelmingly enslaved by other black tribes, and only then sold to white buyers. As Ms. Hurston writes:

One thing impressed me strongly from this three months of association with Cudjo Lewis. The white people had held my people in slavery in America. They had bought us, it is true and exploited us. But the inescapable fact that stuck in my craw, was: my people had sold me and the white people had bought me. That did away with the folklore I had been brought up on—that the white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard ship and sailed away.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies, has urged the founder of the “1619 Project” to acknowledge this history and to directly address the role played by African warlords who kidnapped blacks for the slave trade. “Talk about the African world and the slave trade,” Gates urged Nikole Hanna-Jones (at the 1:42 minute mark), “This is something black people don't want to talk about. But … 90 percent of the Africans who ended up here were the victims of imperial wars – wars between imperial states in Africa – when Africans were capturing Africans and selling them to Europeans along the coast. This has got to be full disclosure. And we’ve got to talk about that.”

And in America, free blacks owned slaves as well. As Larry Koger writes in Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860:

at one time or another, free black slaveowners resided in every Southern state which countenanced slavery and even in Northern states. In Louisiana, Maryland, South Carolina, and Virginia, free blacks owned more than 10,000 slaves, according to the federal census of 1830.

Native Americans owned slaves, too. As explained by Barbara Krauthamer in her book Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South, “Native Americans tribes bought thousands of slaves, and allied with the Confederacy during the Civil War -- and didn’t free their own slaves until a treaty with the United States required such in 1866.”

The 1619 Project initially made another central claim. In the Hannah-Jones introductory essay to the 1619 Project, she wrote “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” That’s false. Gordon S. Wood, one of the nation’s most preeminent historians of the American Revolution, wrote that “I don't know of any colonist who said that they wanted independence in order to preserve their slaves ... No colonist expressed alarm that the mother country [England] was out to abolish slavery in 1776.”

Indeed, as Eric Herschthal writes in “The Science of Abolition: How Slaveholders Became the Enemies of Progress”:

[T]he American Revolution transformed what had been disparate and uncoordinated attacks on slavery into an organized political movement … Patriot leaders responded that they cared little for slavery and would rather see it disappear if only Parliament would let them. They were not being entirely disingenuous, either. In 1772 the Virginia colonial legislature passed a bill to curtail the slave trade, only to see Parliament reject it; two years later, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution in favor of banning slave importations.

And in a December, 2019, letter published in the New York Times, historians Gordon Wood, James M. McPherson, Sean Wilentz, Victoria Bynum and James Oakes expressed “strong reservations” about the 1619 Project generally and requested factual corrections, accusing the authors of a “displacement of historical understanding by ideology.”

Indeed, Sean Wilenz, in his book No Property in Man, describes how how the Constitution's provisions led to abolishing slavery because the Founders rejected any federal right to own property in people. When the South couldn’t fall back on federal constitutional protections for property in men, its leaders had to resort to Civil War, which caused the death of some 600,000 people, with roughly one Union soldier dying for every nine or ten slaves freed, as Wilfred Reilly notes. If the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution hadn’t enshrined noble ideals, opponents of slavery couldn’t have so effectively shamed slavery supporters with their hypocrisy. Pointing out that shameful hypocrisy is what led to slavery’s demise in America. As Wilenz writes:

it took a horrific civil war to achieve emancipation. But the war came only because of undaunted antislavery political activities, the most effective of them claiming the authority of the Constitution. These activities culminated in the rise of the Republican Party, an antislavery mass organization unprecedented in world history … Organized antislavery politics originated in America. In 1775, five days before the battles of Lexington and Concord, ten Philadelphians, seven of them Quakers, founded the first antislavery society in world history, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. The group disbanded during the war, but in 1784, with the Revolution won, it reorganized as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery (also called the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, PAS), and by the end of 1790, at least seven more statewide antislavery societies had appeared, from Rhode Island to as far south as Virginia. When the Federal Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, five northern states as well as the republic of Vermont (which would become the fourteenth state four years later) had either effectively banned slavery outright or passed gradual emancipation laws, commencing the largest emancipation of its kind to that point in modern history.

Martin Luther King specifically drew attention to the hypocrisy exhibited by allowing slavery and discriminatory practices in the face of the universal principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. In his “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King said “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’”

The Vice President of the Confederacy himself recognized that the principles written into the Constitution would ultimately doom slavery. As Brian Villmoare writes in The Evolution of Everything: The Patterns and Causes of Big History:

Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy, in 1861 made his “Cornerstone Speech,” in which he argued that slavery was the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy, and was morally justified for racial reasons: “The prevailing ideas entertained by [Jefferson] and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.”

As Thomas Sowell has pointed out:

Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century – and then it was an issue only in Western civilization. Among those who turned against slavery in the 18th century were George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry and other American leaders. You could research all of the 18th century Africa or Asia or the Middle East without finding any comparable rejection of slavery there. But who is singled out for scathing criticism today? American leaders of the 18th century.

And as Sowell writes in The Economics and Politics of Race:

[In America,] [a]nother historic factor was the American ideology of freedom and democracy … The morality of slavery had seldom been a serious issue in most slave societies in history, but because of the American ideal of freedom the institution of slavery was an anachronism embroiled in controversy from the outset. The American Revolution heightened awareness of the contradiction, and most states outside the South abolished slavery in the decades immediately following independence …

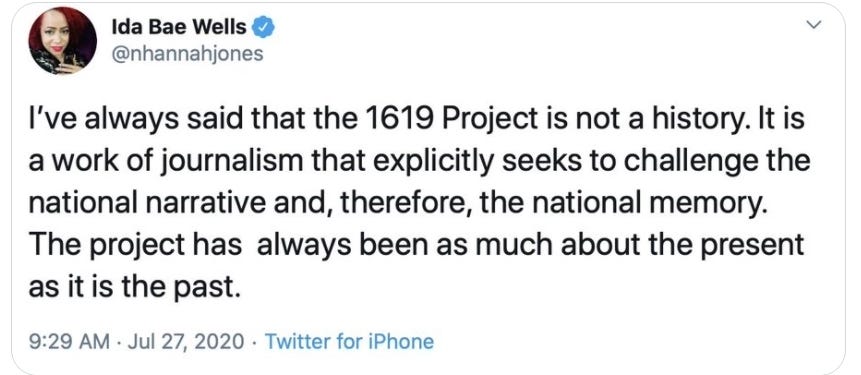

Hannah Jones herself has since admitted that the 1619 project is not true history. She tweeted, “I’ve always said that the 1619 Project is not a history. It is a work of journalism that explicitly seeks to challenge the national narrative and, therefore, the national memory.” She also tweeted “The 1619 Project explicitly denies objectivity.” If Hanna Jones’ current position is that the 1619 Project isn’t history, then in which class would it be taught? A class called “Made-Up-History for Fraudulent Journalists Who Want to Create False Memories?” So the 1619 Project isn’t history after all. It’s identity politics.

Hannah-Jones’ and Kendi’s false narratives recall those of Alex Haley, whose best-selling book Roots was also made into a television series in the 1970’s. Roots achieved unprecedented popularity, as an estimated 140 million people, accounting for over half of the population of the United States, saw the television series. Roots won both a Pulitzer prize and a National book award. Yet his story of slavery, which he claimed was true history, turned out to be a fraud, including its description of black slave Kunta Kinte’s capture in Africa by white slavers. As the New York Times reported,

investigations in Africa and examinations of British colonial records and Lloyd’s shipping documents showed Haley had been mistaken or misled, and there appeared to be no factual bases for Haley’s conclusion that he had actually traced his genealogy back to Kunta Kinte in the village of Juffure, Gambia, and that Kunta Kinte had been captured by white slavers in 1767. The account of Kunta Kinte [accoring to the Times of London] was “provided by a man of notorious unreliability who knew in advance what Haley wanted to hear and who subsequently gave a totally different version of the tale.”

Ultimately, Haley simply admitted his narrative was a myth, saying “I was just trying to give my people a myth to live by.”

Despite this, the Pulitzer Prize Committee has never revoked the prize it awarded Haley for Roots. Nor has the Pulitzer Prize Committee revoked the Pulitzer awarded to Nikole Hannah Jones.

As Wilfred Reilly writes:

[W]hat [really] made the modern Western world unique when it came to slavery? The simple if unpopular answer is: Ending the practice of slavery. It was not keeping captured enemies or plantation serfs in bondage that made the West stand out historically—those practices were universal—but rather letting them go. With all due respect to the brave slave rebels of Haiti or the occasional philosopher within the long Chinese and Indian intellectual traditions, “emancipation”—the widespread belief that people who are not themselves enslaved should vigorously oppose the entire institution of slavery—seems to have been a distinctively and almost uniquely Western idea. Whether it reflected relatively early European industrialization or a rare but genuine escape from human amorality, the freeing of most of the slave population of the earth was a Western (and Christian) triumph. Historian Philip D. Morgan writes in a collection of essays from the Organization of American Historians: Unlike other previous forms of slavery, the New World version did not decline over a long period but came to a rather abrupt end. The age of emancipation lasted a little over one hundred years: beginning in 1776 with the first antislavery society in Philadelphia, through the monumental Haitian Revolution of 1792, and ending with Brazilian emancipation in 1888. An institution that had been accepted for thousands of years disappeared in about a century… [S]lavery was formally declared illegal throughout the United States in 1865. It is well worth remembering the price we paid to reach that point: the shockingly bloody American Civil War—where men and boys not infrequently charged dug-in cannon manned by their brothers—killed 360,222 lads in Union blue, and another 258,000 or so in Confederate Feldgrau. Roughly one in every ten American men of fighting age died during the war: 22.6 percent of Southern white men in their twenties were killed. In some Southern states, the majority of buildings over two stories high were burned; one Union soldier died for every nine to ten slaves who were set free … Between France’s abolition of the practice in 1794 (or Haiti’s in 1804, if you prefer) and Brazil’s in 1888, every major Western nation legally barred slavery. Many other nations did not. While it is considered wildly politically incorrect to point this out, in powerful Muslim and Black African countries where the writ of the West never ran, chattel slavery quite often still exists today. A recent report from the International Labour Organization recently found that, “as of 2016,” more than 40 million people currently “perform involuntary servitude of some kind” in situations that they cannot leave. In other words, they are slaves. Per one widely read commentary on the report: “Today, there could be more people enslaved than at any time in human history. Chattel bondage still happens today . . . particularly in Africa.” The details provided by the ILO and the scholars analyzing its data are striking. Per one standard estimate, “between 529,000 and 869,000” human beings—most of them Black Africans—are currently “bought, owned, sold, and traded by Arab and Black . . . masters” within just five countries in Africa. Global sources estimate that there are currently 700,000 to 1 million desperate Black African migrants living in Libya alone, and that roughly 50,000 of them have been forced into physical or sexual slavery by Arab Libyans. In Nigeria, where essentially all political and tribal violence is Black-on-Black, constant conflict between the sizable Muslim and Christian populations has led to “the growth of terrorist violence in which the taking of ... slaves has become a source of compensation.” Despite what some might call the best efforts of the media, some of this barbarity has attracted global public attention. An actual public slave auction was held in Libya and videotaped by undercover CNN reporters in 2017, and the hash-tag #BringBackOurGirls trended worldwide after Boko Haram fighters and slave traders kidnapped 276 Christian schoolchildren in spring of 2014 … Even a few open slave societies continue to exist today, per the ILO and website sources like www.iAbolish.org. In the Islamic republic of Mauritania, “the very structure of society reinforces slavery.” A racialized caste system still exists, where—in roughly this order—Berbers, lighter-skinned Arabs known as beydanes, and Islamized free Blacks called haratin completely dominate a group of Black chattel slaves referred to as abid or abeed.* The slave population is sizable: the U.S. State Department has estimated it at “just” 30,000 to 90,000 people, but deep-cover research by CNN in 2011 placed the real number at between four and seven times State’s highest estimate, with the network’s reporters and analysts estimating that “10% to 20% of the [Mauritanian] population lives in slavery.” Mauritanian slaves live very much as slaves always have: their yoke is not a light one. Perhaps because of the backlash to this practice in Libya or Algeria, few if any open markets exist, but all slaves are held as chattels and most are born out of forced intercourse, “the master raping black slave women or ordering necessary episodes of sexual activity [‘breeding’].” Slaves are often used as a crude form of currency, serving “as substitutes for money in the settling of gambling debts,” being privately traded between masters in exchange for other people or goods like rice, and often being available for short-term rental for whatever purpose. Like unfree people everywhen, they have no say in any of this, and can be (and often are) beaten or killed for attempting to escape their state of bondage. Interestingly, sources almost invariably describe Mauritania as one of the countries in the world furthest from the West, an “endless sea of sand dunes” where the cuisine, dominant religion, and daily patterns of life show little if any European influence. And that may be the problem. When analyzed by serious people, across the sweep of history, slavery is revealed to have been not a “Western” practice but rather a universal one largely ended by Western arms. Where those arms reached never, or only briefly, it often continues to this day.

In the next essay, I’ll discuss how academia has tended to embrace the false narratives of Kendi, DiAngelo, and Hannah Jones, rather than encourage their correction, and the negative ramifications of that.

Links to all essays in this series: Part1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

Collected essays in this series

Short video documentary on problems with popular critical race theory texts

Harvard Law School flashback