Part 2 -- The False Certainty of a Trick Coin

A Critique of Kendi, DiAngelo, Hannah Jones, and Critical Race Theory

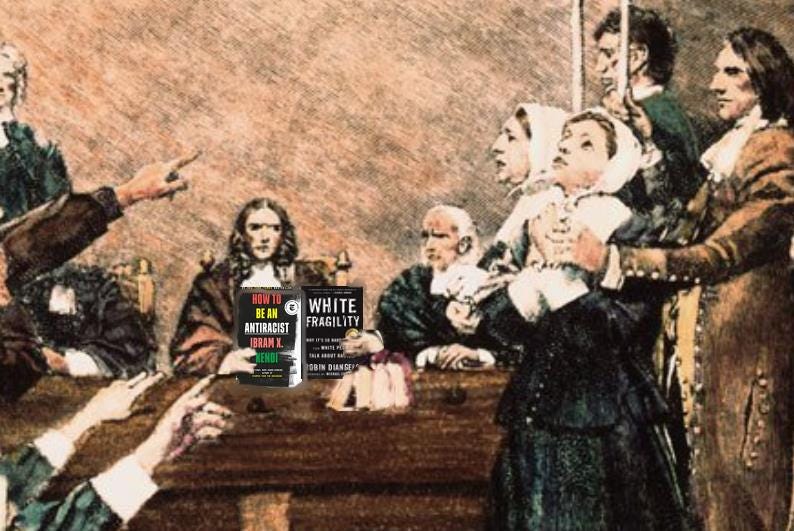

In my previous essay (Part 1) I described how Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo’s assumption that all outcome disparities in society between groups of people sorted by race are the result of racism recalls the assumption of medieval witch hunters that community misfortunes were the result of witchcraft. In this essay I’ll describe how that assumption of Kendi and DiAngelo is belied by facts.

Professor Teofilo F. Ruiz, in his Great Courses lecture series on “The Terror of History: Mystics, Heretics, and Witches in the Western Tradition,” describes how the witch craze started at a time when belief preceded knowledge. As he explains in Lecture 17:

Knowledge and belief are two very different things. Throughout the Middle Ages, the philosophical position was that you believe in order to understand. That is to say, belief comes before knowledge … The way in which you get to knowledge is first by believing and then moving to specific knowledge … By the time we get to the late fifteenth century, we enter into the kind of pre-scientific revolution [that] breaks down the relationship between belief and knowledge, and they become two very separate points of view. This is going to lead eventually to the scientific revolution and in many respects the scientific revolution is going to lead to the end of the witch craze.

Kendi and DiAngelo, however, are stuck back in the fourteenth century: their professed belief in systemic racism precedes, and trumps, any knowledge of the myriad other causes of racial disparities.

Karen Fields, in her book Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life, explicitly compares popular modern views on race to rural folk religions and witchcraft, as both views are often based on belief rather than knowledge:

Here, paraphrased, is an exchange between an unbelieving interviewer with the American children or grandchildren of European immigrants who believed in the evil eye:

Q: How does the evil eye work?

A: Some people are known to have it.

Q: How do you know that?

A: I have seen X’s remedy work.

Q: Is it always effective?

A: I know for a fact that it worked for So-and-so.

Today, as in the sixteenth century, logical hopscotch of that kind is the warp and woof of banal sociability. The talkers respond to, but ignore, the interviewer’s question about the mechanism of the evil eye. It exists, period. The interviewer does not press, and does not need to. Those present do not query assumptions, the nature of available evidence, or the coherence of their reasoning from that evidence. What they know they know intimately, but not well. Such is the stuff that racecraft is made of. It occupies a middle ground between science and superstition, an invisible realm of collective understandings, a half-lit zone of the mind’s eye … In my work on racecraft, I have been struck over and over again by such intellectual commonalities with witchcraft as circular reasoning, prevalence of confirming rituals, barriers to disconfirming factual evidence, self-fulfilling prophecies, multiple and inconsistent causal ideas, and colorfully inventive folk genetics.

To Kendi and DiAngelo, racism is the new evil eye, and they are the inquisitors whose role is to see it everywhere. And as Cullen Murphy writes in God’s Jury (describing the witch hunt craze of medieval times):

The inquisitors -- like their masters and their theological associates -- shared an outlook of moral certainty. They believed that they enjoyed personal access to an unchanging truth … One twentieth-century historian concludes, “The medieval inquisitors had perfected techniques by which the very fabric of reality could be altered.”

Kendi, too, attempts to alter the fabric of reality by assuming racism is the cause of all disparities among people grouped by race, and then basing all subsequent understanding on the presumed truth of that assumption. Kendi writes in How to Be an Antiracist that “The opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘antiracist.’” A “racist,” he explains “allows racial inequities [differences in outcome] to persevere.” But as Thomas Sowell has explained, if several criteria need to be met for any given outcome, then even the smallest variations in a group’s aggregate odds of meeting any of those criteria will inevitably produce different outcomes for the group generally:

When there is some endeavor with five prerequisites for success, then by definition the chances of success in that endeavor depend on the chances of having all five of those prerequisites simultaneously. Even if none of these prerequisites is rare -- for example, if these prerequisites are all so common that chances are two out of three that any given person has any one of those five prerequisites -- nevertheless the odds are against having all five of the prerequisites for success in that endeavor. When the chances of having any one of the five prerequisites are two out of three, as in this example, the chance of having all five is two-thirds multiplied by itself five times. That comes out to be 32/243 in this example, or about one out of eight … What does this little exercise in arithmetic mean in the real world? … [W]e should not expect success to be evenly or randomly distributed among individuals, groups, institutions or nations in endeavors with multiple prerequisites …

That being the case, it’s no surprise there are indeed statistical disparities among all groups, and within groups. As Coleman Hughes has written, again drawing on the works of Thomas Sowell:

Sowell has challenged that premise [that statistical equality in outcomes would be the norm, absent racism] more persuasively than anyone. One way he pressure-tests this assumption is by finding conditions in which we know, with near-certainty, that racial bias does not exist, and then seeing if outcomes are, in fact, equal. For example, between white Americans of French descent and white Americans of Russian descent, it’s safe to assume that neither group suffers more bias than the other -- if for no other reason than that they’re hard to tell apart. Nevertheless, the French descendants earn only 70 cents for every dollar earned by the Russian-Americans. Why such a large gap? Sowell’s basic insight is that the question is posed backward. Why would we think that two ethnic groups with different histories, demographics, social patterns, and cultural values would nevertheless achieve identical results? … It’s not a myth that some American minorities have higher incomes, better test scores, and lower incarceration rates than white Americans.

Regarding student test scores, Kendi rejects their validity, but in a way that undermines his presumption that it’s racism alone that causes outcome disparities. He claims standardized tests in education don’t show any objective “achievement gap” in education because different “environments” experienced by whites and blacks simply lead to different “types” of achievement -- not to different levels of objective understanding. As he explains, “The use of standardized tests to measure aptitude and intelligence is one of the most effective racist policies ever devised to degrade Black minds and legally exclude Black bodies.” He posits instead, “What if different environments lead to different kinds of achievement rather than different levels of achievement?”

But taking his argument on its own terms, if different environments can lead to disparities in achievement outcomes (be it “kinds” of achievement -- whatever that means -- or “levels” of achievement), how can the assumption of racism as the exclusive cause of other disparities be justified? Environment includes culture. The Dutch sociologist Geert Hofstede says culture is the software of the mind -- the way your environment has primed you to see and react to the world. And differences in how one is primed to see the world will lead to differences in outcomes. According to research by the Brookings Institution’s Michael Hansen and Diana Quintero, for example, black high-school students spend a little more than a quarter of the time on homework that Asian students do, and half the time of white students. Differences in culture, independent of racism, can lead to “better” or “worse” choices in certain instances.

Kendi himself seems to recognize this in his children’s book, Antiracist Baby, in which he writes the following at the end of the book (concerning racist choices) under the title “Dear Parents and Caregivers”: “

we don’t consider them to be ‘a bad kid’ when they do something wrong, but we must acknowledge that they made a bad choice. They have an opportunity to make a better choice the next time … Being measured by our actions allows us to continue to grow.

Surely one’s cultural environment can contribute to one’s making “good” or “bad” choices, yet Kendi insists in How to Be an Antiracist” that “To be antiracist is to see all cultures in all their differences as on the same level, as equals.” But if some cultures can tend toward some bad choices, and others toward better choices (DiAngelo and Kendi themselves repeatedly reference the problems of “white culture”), then cultures can be unequal insofar as they are evaluated under any standard aiming to define “good” or “bad.”

Complicating things further for Kendi is Thomas Sowell’s observation, in his book Wealth, Poverty, and Politics, that:

group differences in results on particular tests are often taken to mean that those tests are “biased,” when the scores on these tests convey differences among the participants which these tests are accused of causing by asking questions geared to a white culture, for example— even when Asian Americans in fact score higher than whites on these tests.

But as Sowell further explains:

The way children are raised also differs greatly— and consequentially— from group to group and from one income level to another. A study found that American children in families where the parents are in professional occupations hear 2,100 words an hour, on average. Children whose parents are working class hear an average of 1,200 words an hour— and children whose family is on welfare hear 600 words an hour. What this means is that, over the years, a ten-year-old child from a family on welfare will have heard not quite as many words at home as a three-year-old child whose parents are professionals. Child-rearing practices differ by race, as well as by class. White American parents play with, talk to and listen to their children three times as often as black American parents. Black parents, on average, have less than half as many books in their homes as white American parents, and that cannot be solely a matter of economics, because black parents in the highest socioeconomic quintile have slightly fewer books in their homes than white parents in the lowest socioeconomic quintile.

Sowell, writing in the early 1980’s in his book The Economics and Politics of Race, makes the following points regarding how disparities among racial, cultural, or other groups are the result of a myriad of factors among which racism is only one.

Regarding people of Chinese ancestry, he writes:

The younger generation of Chinese Americans carried into the schools the same sense of purpose and perseverance that characterized the Chinese in many activities in countries around the world. As school children, they were better behaved and more hard-working than white students. Later, in colleges and universities, the Chinese specialized in the more difficult and demanding and lucrative fields such as medicine, the natural sciences, and engineering. As of 1940, the proportion of Chinese who worked in professional-level occupations was less than half that among whites. But by 1960, the Chinese had passed whites, and by 1970 they had widened the gap, now having higher proportions in such occupations than any other American ethnic group. Among Chinese males, 30 percent worked in professional and technical fields, double the proportion among white males. Moreover, a higher percentage of Chinese men were engineers and college teachers of physics, mathematics, and chemistry. The income of Chinese Americans passed the national average in 1959, and that gap has also widened. In the wake of these economic achievements came more social recognition …

Regarding people of Irish ancestry, he writes:

[Regarding the Irish], [w]riting in the 1830’s, Gustave de Beumont said “I have seen the Indian in his forests and the Negro in his chains and thought as I contemplated their pitiable condition that I saw the very extreme of human wretchedness. But I did not then know the condition of unfortunate Ireland.” This was not mere exaggeration for effect. The average slave in the United States had a life expectancy of 36 years. The average Irish peasant, 19 … When the slaves were freed, they were destitute by American standards, “but not as poor as the Irish peasants,” according to W.E.B. DuBois … [In America,] when the Irish moved into many neighborhoods, the exodus of non-Irish residents began. In parts of nineteenth-century New York, Negroes were preferred to the Irish as tenants. Employment advertisements, even for lowly jobs, often used the stock phrase “No Irish need apply.” More delicate advertisers would ask for a Protestant applicant, but others more bluntly said “Any color or country, except Irish.” … The growing acculturation of the Irish slowly produced tangible economic results [in America] although the Irish were the slowest rising European ethnic group in the United States … [T]he second-generation Irish were increasingly white collar workers who were occasionally professionals … Irish-Americans today have equaled or exceeding the American national average in income and IQ … Historically, it represents one of the great social transformations of people.

Regarding people of Jewish ancestry, Sowell writes:

Barriers went up against Jews in general in various occupations, businesses, and industries, as well as in social settings such as clubs, or hotels. Jews crowded into those sectors that were open to them and created their own industries … By 1969, Jewish family income in the United States was 72 percent above the national average. More than one-fourth of all Nobel Prizes won by Americans had been won by Jewish-Americans.

Regarding blacks of Brazilian ancestry, he writes:

Though racism as such is not as prominent a feature of Brazilian society as of other multi-racial societies, Brazil has highly rigid class lines and a distribution of income that is much more unequal than that of the United States, for example … For all its more relaxed race relations, Brazil has larger black-white disparities than the United States in education, and in political participation.

And as Sowell summarizes:

Much contemporary social philosophy proceeds as if different patterns of group representation in various occupations, institutions, activities, or income levels must reflect discriminatory decisions by others -- that is, as if there were no substantial cultural or other differences among the various groups themselves. Yet this key assumption is nowhere demonstrated and is in many ways falsified, even in activities in which no discrimination is possible. People are not proportionately represented. Activities solely within the discretion of the individual, choices among television programs to watch or card games to play, the age of marriage, or the naming of children, show widely differing patterns between different racial, ethnic, and national groups … American racial and ethnic groups differ enormously in characteristics ranging from age to regional distribution to diverse cultural backgrounds. Many of these characteristics have a major impact on the economic conditions of racial and ethnic groups, even though they attract much less attention than race or racism … Among non-white Americans, some groups, Japanese and Chinese, earned more than whites. Some, Filipinos and West Indians, earned about the same. And others, Indians and native blacks, earned substantially less. Still other groups with a majority classified as white, Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, earned substantially below the national average. In short, non-white groups are spread across the income spectrum, just as white groups are. On the whole, whites earn more than non-whites, but only because, statistically, about 90 percent of non-whites in the United States are native black Americans, not because non-white groups are all consigned to lower economic positions. Japanese-Americans earn higher incomes than Americans of German, Italian, Irish, Polish, or Anglo-Saxon ancestry. So do second-generation black West Indians … The pervasive Jim Crow laws that confronted generations of blacks in the South were unique. But the worst years of anti-Asian laws and policies on the West Coast were a close second, featuring vigilante violence as well as legal discrimination and public hostility. Yet what is surprising is the cold fact that there has been little correlation between the degree of discrimination in history and the economic results today … It would be even more difficult to claim that Puerto Ricans have historically encountered a level of discrimination comparable to that of blacks, who have higher occupational status and 20 percent higher incomes. There may well be color prejudice against the multi-colored Puerto Ricans, but it would be hard to claim that it is stronger than color prejudice against black West Indians, who have 50 percent higher family incomes.

All this goes to show that Kendi’s moral certainty that statistical disparities are due to racism is an exercise in politicized reason. Politicized reason focuses on a single cherry-picked system when in fact there are many more systems operating simultaneously. Focusing on “systemic racism” ignores all the other systems, both internal and external, governed by incentive structures, family and upbringing, social programs and laws, and thousands of other systems, all operating at once, and some having much more influence on outcomes than others. Non-politicized reason looks to examine all systems, and to determine how they all interact to produce any given result.

A form of politicized reasoning was the basis for the witch hunts as well. As Adam Jortner relates in his Great Courses series American Monsters, “17th century Puritans did not believe witches left physical evidence. The harm they did – sick cattle, failed crops, injured children – was the evidence.” Just as the Puritans pointed to bad results as proof of witchcraft, Kendi points to aggregate disparities between groups as proof of racism.

The witch craze returned briefly in the 1980’s and 1990’s (the era of the “Satanic Panic”) as people saw signs of Satanic worship in things like heavy metal music and board games. As Jortner states:

The logic here was if you see your teenager acting like a teenager, it was evidence for a deep Satanic conspiracy. And don’t take no for an answer. “If an individual is involved in Satanic activity,” BAD [a group called “Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons”] wrote to parents, “they will deny a great deal to protect other members of the group as well as the Satanic philosophy … Journalists began investigating these claims and noticing that procedure was not being followed and that many of the “experts” in Satanism made claims with no basis in fact.

And so this phenomenon continues today, except “Satanic influence” has been replaced by “racism.”

In the next essay, I’ll look to some of the more significant systems that influence disparities among different groups of people.

Links to all essays in this series: Part1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12

Collected essays in this series

Short video documentary on problems with popular critical race theory texts

Harvard Law School flashback