In this essay, we’ll look at data on perceptions of personal experience with racism, and attitudes on race and racism.

Perceptions of Personal Experience with Racism

An analysis of survey data found that instances of discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation, and age, are very rare. The researchers concluded:

Using a representative sample of American respondents who reflect a variety of racial and ethnic groups, the current study examined perceived experiences of discrimination. Our results indicate that the majority of the sample reported either no experience with discrimination or that it had happened only rarely. Moreover, of those reporting having experienced discrimination, the majority suggested that unique and perhaps situationally specific factors other than race, gender, sexual orientation, and age were the cause(s) of discrimination.

More generally, tolerance for minority groups is positively associated with countries that have greater economic freedom.

In a letter to the Governor of California, Clarence Jones, Martin Luther King’s chief speechwriter in the 1960's, objected to the teaching of students that the civil rights movement did not, as it did, dramatically transform Americans’ views of race for the better:

I write this letter to you with great dismay, and great concern for the perversion of history that is being perpetrated by the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (ESMC). If this model curriculum is approved, it will inflict great harm of millions of students in our state. It is a fact that the Black Freedom Movement of the 1950s and 1960s under Dr. King’s leadership transformed our country, overthrowing a century of Jim Crow segregation and white supremacist terror throughout the former Confederate states. This fact, which I had thought was well known to all educated persons, has been removed from the ESMC. This is morally unacceptable and renders the entire curriculum suspect.

Attitudes on Race and Racism

Interestingly, according to one poll taken almost a decade ago, blacks were more likely to think most blacks are racist than to think most whites are. Blacks were also more likely than liberals (regardless of race) and Democrats to think most blacks are racist. Blacks were also less likely than liberals to think most whites are racist.

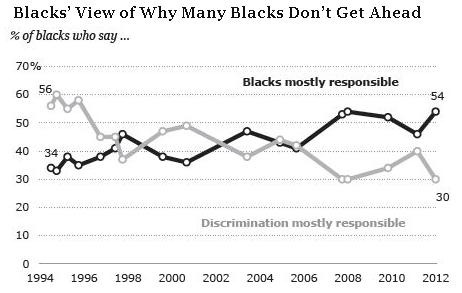

Whereas thirty years ago, many more blacks reported that discrimination rather than individual responsibility was the reason why many blacks don’t get ahead, two decades later the opposite was true.

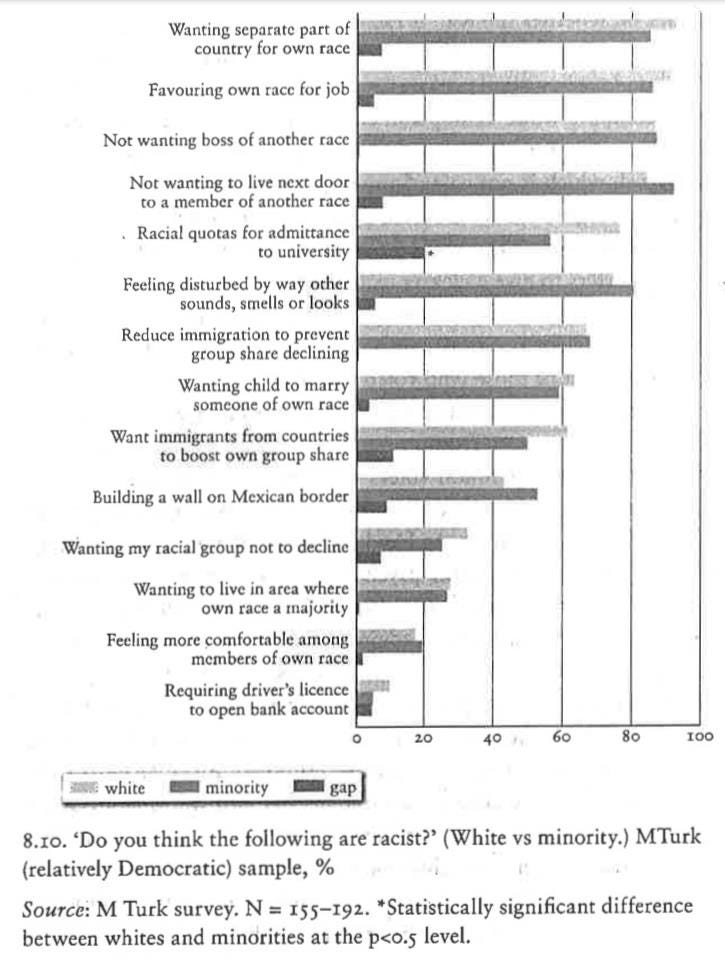

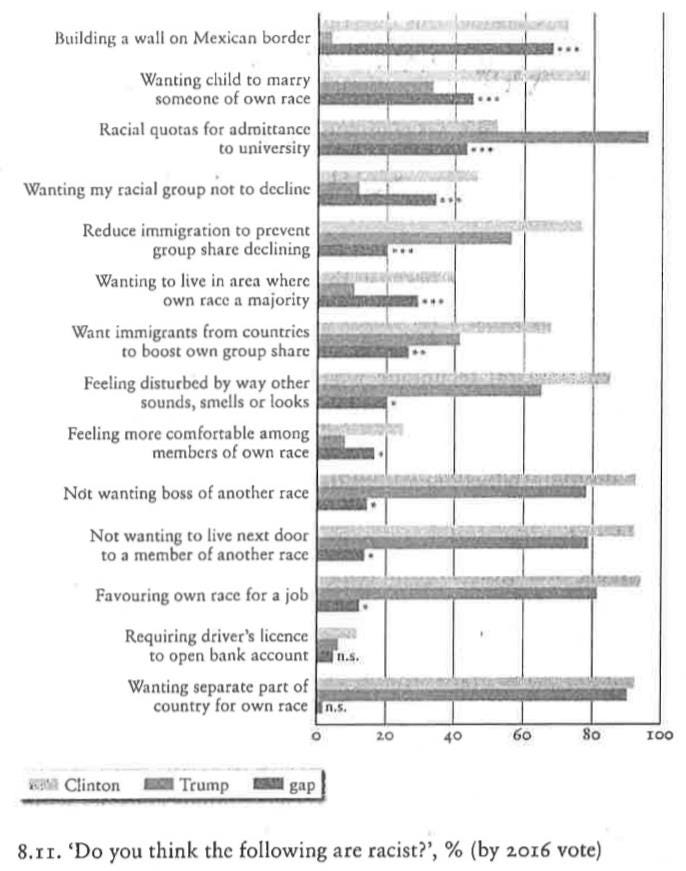

As Eric Kaufmann points out, “whites and minorities in America largely agree on what is and isn’t racist. The only significant difference is over whether racial quotas in university admissions are racist, and, even here, a majority of both non-whites (57 percent) and whites (77 percent) say they are … whites and minorities place the racism/non-racism boundary in a similar place across a wide range of questions, but when we compare white Trump and Clinton voters, big partisan divides open up.”

As Adrian Wooldridge points out in The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World, “numerical targets are both unpopular and counterproductive. The majority of Americans (including majorities of blacks) say that they are opposed to affirmative action and, in the 2020 ballot initiative, a majority of Californians voted against it.”

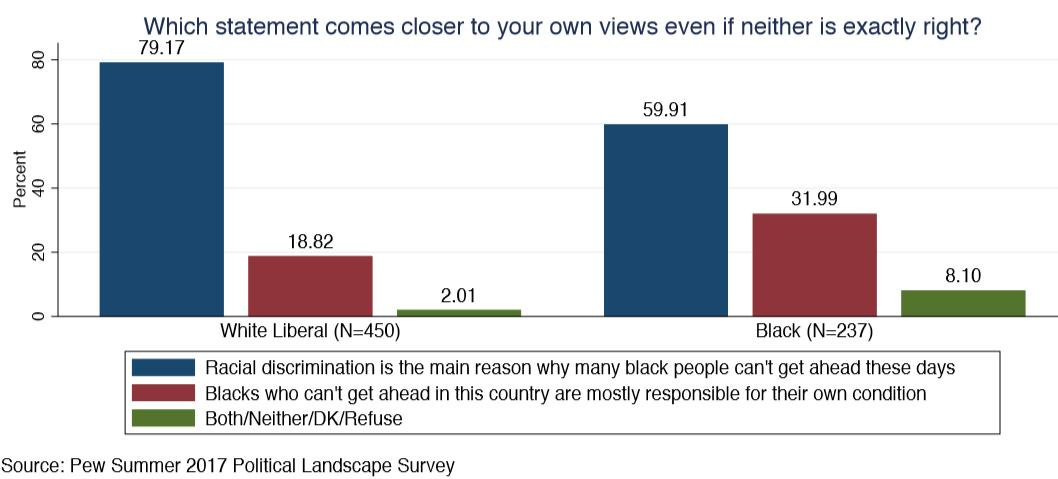

White liberals now have opinions on whether discrimination is a factor holding back black advancement that are much to the left of those of blacks themselves. White liberals are to the left of black Democrats, placing a much stronger emphasis than blacks on the role of discrimination and much less emphasis on the importance of individual effort. Among white liberals, according to Pew survey data collected in 2017, 79 percent agreed that “racial discrimination is the main reason why many black people can’t get ahead these days.” Nineteen percent agreed that “blacks who can’t get ahead in this country are mostly responsible for their own condition,” according to a detailed analysis of the Pew data provided by Zach Goldberg. Among blacks, 60 percent identified discrimination as the main deterrent to upward mobility for blacks, and 32 percent said blacks were responsible for their condition.

Researchers have shown that statements that some call “racist dog whistles” are in fact not perceived as racist by majorities in the black community. As Ian Haney López and Tory Gavito note in the New York Times:

With the help of two liberal pollsters, Joshua Ulibarri and Celinda Lake, we … polled large cohorts of whites and African-Americans. The results are sobering. We began by asking eligible voters how “convincing” they found a dog-whistle message lifted from Republican talking points. Among other elements, the message … called for “fully funding the police, so our communities are not threatened by people who refuse to follow our laws.” Almost three out of five white respondents judged the message convincing. More surprising, exactly the same percentage of African-Americans agreed, as did an even higher percentage of Latinos.

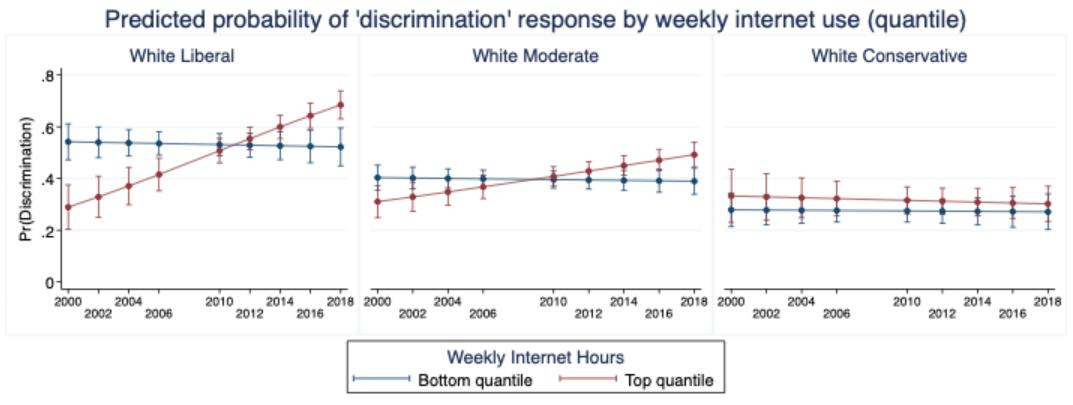

Zach Goldberg also points out that “we also see that the predicted probability of a ‘discrim[ination]’ response from those placing in the bottom quantile of weekly internet use remains more or less flat across time, while the odds of this response from the top quantile shows a significant secular increase,” indicating that increased exposure to claims of racism on the internet may lead people to think more discrimination is actually occurring.

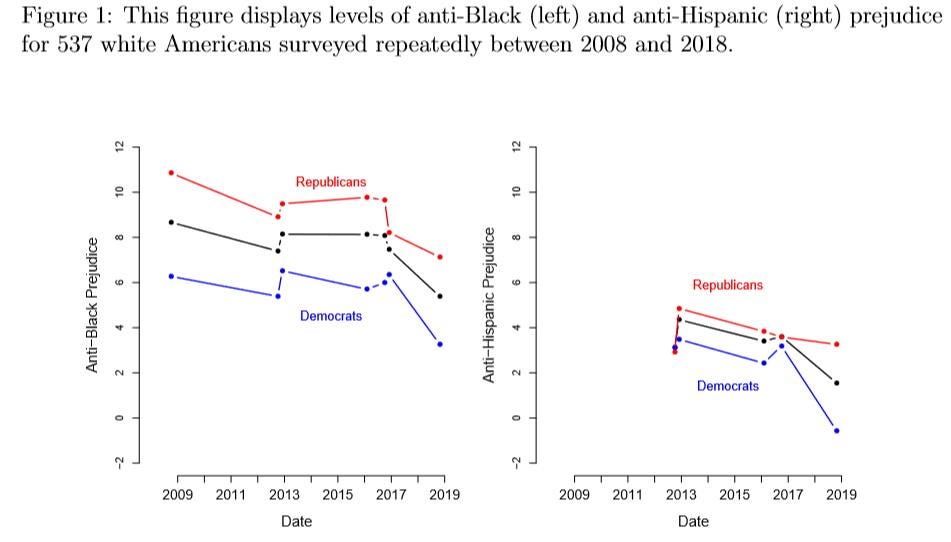

A University of Pennsylvania study found that expressions of racism among white Americans declined following the 2016 presidential election, concluding that “We find that via most measures, white Americans’ expressed anti-Black and anti-Hispanic prejudice declined after the 2016 campaign and election, and we can rule out even small increases in the expression of prejudice. These results suggest the limits of racially charged rhetoric’s capacity to heighten prejudice among white Americans overall.”

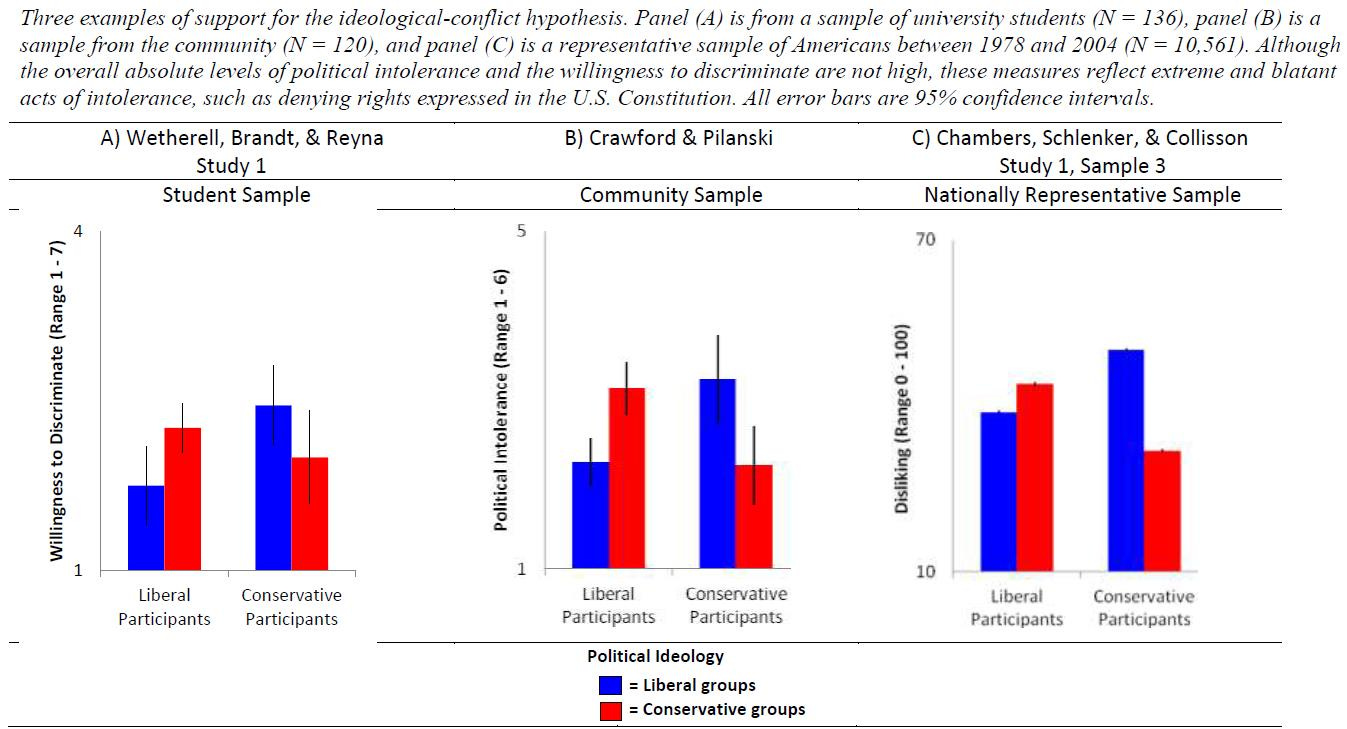

Generally, researchers have found that both liberals and conservatives express intolerance toward groups generally associated with holding ideological views contrary to their own, and that it is generally the ideological views of the subject, not race or other factors, that is the source of the intolerance.

Regarding stereotypes generally, a meta-analysis of research on stereotypes and their accuracy found that “Our review has shown … that it is unusual (but not unheard of) for stereotypes to be highly discrepant from reality, that the correlations of stereotypes with criteria are among the largest effects in all of social psychology, that people rarely rely on stereotypes when judging individuals, and that, sometimes, even when they do rely on stereotypes, it increases rather than reduces their accuracy.”

Also, the test most often used by psychologists to measure implicit bias has been shown to be far too unreliable for use in drawing any conclusions. I explored the inherent flaws in that test in a previous essay.

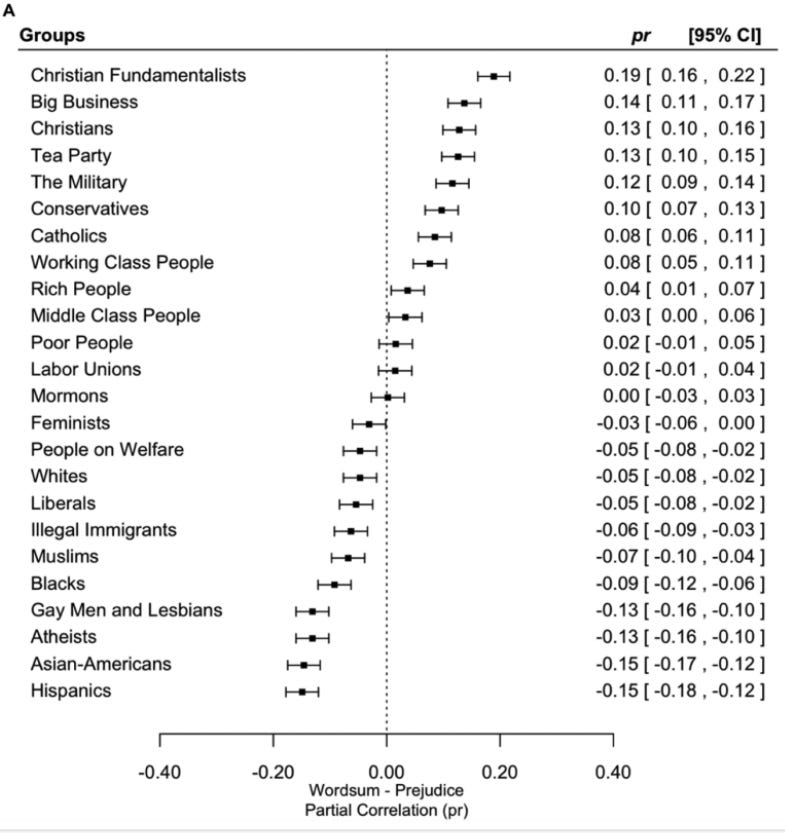

Regarding inter-group bias generally, researchers have found that “people with both relatively higher and lower levels of cognitive ability show approximately equal levels of intergroup bias but toward different sets of groups,” with higher cognitive ability people generally expressing bias against big business, conservatives, the military, and working class people.

The next essay in this series will explore data on racial pay gaps, and some perverse outcome preferences based on perceptions of racism.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6