Data on Racism – Part 2

The truly disadvantaged.

In this essay, we’ll look at Professor William Julius Wilson’s 1987 book The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Written as it was over 25 years ago by a prominent black Harvard sociologist, it’s interesting to note both its recognition that even back then evidence was mounting that racism was not anything like a primary cause of disparities among people grouped by race, and its insights that have held up so well over time.

Wilson contrasts the situations generally experienced by blacks both before and after 1970, a contrast few are aware of today:

In the mid-1960s, urban analysts began to speak of a new dimension to the urban crisis in the form of a large subpopulation of low-income families and individuals whose behavior contrasted sharply with the behavior of the general population. Despite a high rate of poverty in ghetto neighborhoods throughout the first half of the twentieth century, rates of inner-city joblessness, teenage pregnancies, out-of-wedlock births, female-headed families, welfare dependency, and serious crime were significantly lower than in later years and did not reach catastrophic proportions until the mid-1970s. These increasing rates of social dislocation signified changes in the social organization of inner-city areas. Blacks in Harlem and in other ghetto neighborhoods did not hesitate to sleep in parks, on fire escapes, and on rooftops during hot summer nights in the 1940s and 1950s, and whites frequently visited inner-city taverns and nightclubs. There was crime, to be sure, but it had not reached the point where people were fearful of walking the streets at night, despite the overwhelming poverty in the area. There was joblessness, but it was nowhere near the proportions of unemployment and labor-force nonparticipation that have gripped ghetto communities since 1970. There were single-parent families, but they were a small minority of all black families and tended to be incorporated within extended family networks and to be headed not by unwed teenagers and young adult women but by middle-aged women who usually were widowed, separated, or divorced. There were welfare recipients, but only a very small percentage of the families could be said to be welfare-dependent. In short, unlike the present period, inner-city communities prior to 1960 exhibited the features of social organization — including a sense of community, positive neighborhood identification, and explicit norms and sanctions against aberrant behavior.

Wilson paints a vivid picture of the transformation of predominantly black communities after 1970:

Indeed, in the 1940s, 1950s, and as late as the 1960s such communities featured a vertical integration of different segments of the urban black population. Lower- class, working-class, and middle-class black families all lived more or less in the same communities (albeit in different neighborhoods), sent their children to the same schools, availed themselves of the same recreational facilities, and shopped at the same stores. Whereas today’s black middle-class professionals no longer tend to live in ghetto neighborhoods and have moved increasingly into mainstream occupations outside the black community, the black middle-class professionals of the 1940s and 1950s (doctors, teachers, lawyers, social workers, ministers) lived in higher-income neighborhoods of the ghetto and serviced the black community. Accompanying the black middle-class exodus has been a growing movement of stable working-class blacks from ghetto neighborhoods to higher-income neighborhoods in other parts of the city and to the suburbs. In the earlier years, the black middle and working classes were confined by restrictive covenants to communities also inhabited by the lower class; their very presence provided stability to inner-city neighborhoods and reinforced and perpetuated mainstream patterns of norms and behavior. This is not the situation in the 1980s. Today’s ghetto neighborhoods are populated almost exclusively by the most disadvantaged segments of the black urban community, that heterogeneous grouping of families and individuals who are outside the mainstream of the American occupational system. Included in this group are individuals who lack training and skills and either experience long-term unemployment or are not members of the labor force, individuals who are engaged in street crime and other forms of aberrant behavior, and families that experience long-term spells of poverty and/or welfare dependency. These are the populations to which I refer when I speak of the underclass.

Wilson then describes the rise of female-headed families in those urban communities since 1970:

Indeed, these long- term poor constitute about 60 percent of those in poverty at any given point in time and are in a poverty spell that will last eight or more years. Furthermore, families headed by women are likely to have longer spells of poverty— at a given point in time, the average child who became poor when the family makeup changed from married- couple to female- headed is in the midst of a poverty spell lasting almost twelve years … Long-term welfare mothers tend to belong to racial minorities, were never married, and are high school dropouts.

Wilson writes it was clear by the 1980’s that increased single parenthood in the black community led to increased dependency on welfare programs:

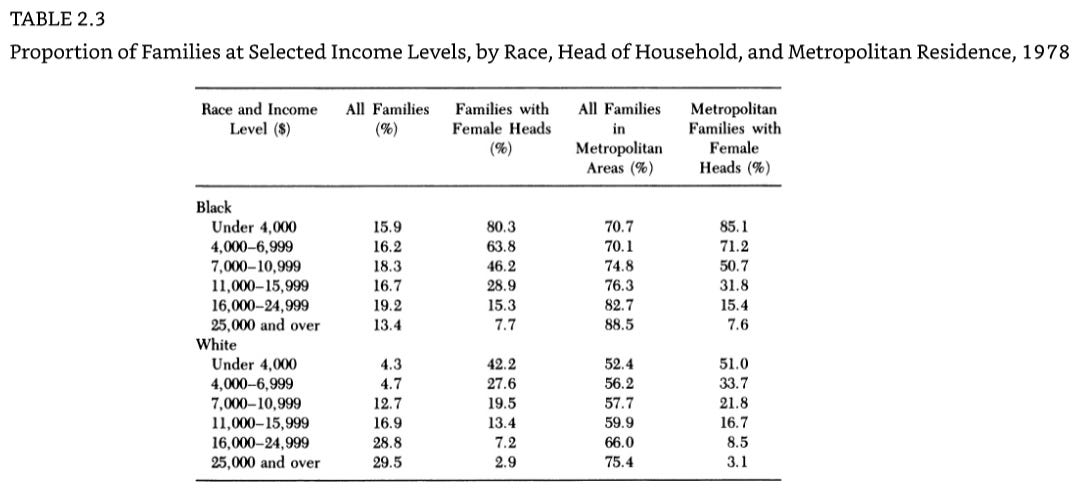

The relationship between level of family income and family structure is even more pronounced among black families. As shown in table 2.3, whereas 80 percent of all black families with incomes under $4,000 were headed by women in 1978, only 8 percent with incomes of $25,000 or more were headed by women; in metropolitan areas, the difference was even greater … The rise of female-headed families among blacks corresponds closely with the increase in the ratio of out-of-wedlock births. Only 15 percent of all black births in 1959 were out of wedlock. This figure jumped to roughly 24 percent in 1965 and 57 percent in 1982, almost five times greater than the white ratio … These developments have significant implications for the problems of welfare dependency. In 1977 the proportion of families receiving AFDC that were black (43 percent) slightly exceeded the proportion that were white other than Spanish (42.5 percent), despite the great difference in total population.

This was not always the case, and indeed a much larger percentage of black families were intact in the decades immediately following the abolition of slavery:

In the early twentieth century the vast majority of both black and white low-income families were intact. Although national information on family structure was not available before the publication of the 1940 census, studies of early manuscript census forms of individual cities and counties make it clear that even among the very poor, a substantial majority of both black and white families were two-parent families. Moreover, most of the women heading families in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were widows. Evidence from the 1940 census indicates that divorce and separation were relatively uncommon. It is particularly useful to consider black families in historical perspective because social scientists have commonly assumed that the recent trends in black family structure that are of concern in this chapter could be traced to the lingering effects of slavery. E. Franklin Frazier’s classic statement of this view in The Negro Family in the United States informed all subsequent studies of the black family, including the Moynihan report. But recent research has challenged assumptions about the influence of slavery on the character of the black family. Reconstruction of black family patterns from manuscript census forms has shown that the two-parent, nuclear family was the predominant family form in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Historian Herbert Gutman examined data on black family structure in the northern urban areas of Buffalo and Brooklyn, New York; in the southern cities of Mobile, Alabama, of Richmond, Virginia, and of Charleston, South Carolina; and in several counties and small towns during this period. He found that between 70 percent and 90 percent of black households were “male-present” and that a majority were nuclear families. Similar findings have been reported for Philadelphia, for rural Virginia, for Boston, and for cities of the Ohio Valley. This research demonstrates that neither slavery, nor economic deprivation, nor the migration to urban areas affected black family structure by the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Wilson then describes the unwillingness of many of those with a “liberal perspective” to honestly address the obvious “social pathologies” that developed post-1970 in inner city communities:

The liberal perspective on the ghetto underclass has become less persuasive and convincing in public discourse principally because many of those who represent traditional liberal views on social issues have been reluctant to discuss openly or, in some instances, even to acknowledge the sharp increase in social pathologies in ghetto communities. One approach is to avoid describing any behavior that might be construed as unflattering or stigmatizing to ghetto residents, either because of a fear of providing fuel for racist arguments or because of a concern of being charged with “racism” or with “blaming the victim.” Indeed, one of the consequences of the heated controversy over the Moynihan report on the Negro family is that liberal social scientists, social workers, journalists, policymakers, and civil rights leaders have been, until very recently, reluctant to make any reference to race at all when discussing issues such as the increase of violent crime, teenage pregnancy, and out-of-wedlock births … [O]ne cannot deny that there is a heterogeneous grouping of inner-city families and individuals whose behavior contrasts sharply with that of mainstream America. The real challenge is not only to explain why this is so, but also to explain why the behavior patterns in the inner city today differ so markedly from those of only three or four decades ago … [L]iberals became increasingly reluctant to research, write about, or publicly discuss inner- city social dislocations following the virulent attacks against Moynihan. Indeed, by 1970 it was clear to any sensitive observer that if there was to be research on the ghetto underclass that would not be subjected to ideological criticism, it would be research conducted by minority scholars on the strengths, not the weaknesses, of inner- city families and communities. 37 Studies of ghetto social pathologies, even those organized in terms of traditional liberal theories, were no longer welcomed in some circles. Thus, after 1970, for a period of several years, the deteriorating social and economic conditions of the ghetto underclass were not addressed by the liberal community as scholars backed away from research on the topic, policymakers were silent, and civil rights leaders were preoccupied with the affirmative action agenda of the black middle class.

Wilson then makes clear that, while greater historical impoverishment certainly followed from slavery and racial subjugation, the much more recent pathologies prevalent in urban communities cannot plausibly be deemed to have been caused chiefly by that historical subjugation:

I should like to emphasize that no serious student of American race relations can deny the relationship between the disproportionate concentration of blacks in impoverished urban ghettos and historic racial subjugation in American society. But to suggest that the recent rise of social dislocations among the ghetto underclass is due mainly to contemporary racism, which in this context refers to the “conscious refusal of whites to accept blacks as equal human beings and their willful, systematic effort to deny blacks equal opportunity,” is to ignore a set of complex issues that are difficult to explain with a race-specific thesis. More specifically, it is not readily apparent how the deepening economic class divisions between the haves and have-nots in the black community can be accounted for when this thesis is invoked, especially when it is argued that this same racism is directed with equal force across class boundaries in the black community. Nor is it apparent how racism can result in a more rapid social and economic deterioration in the inner city in the post-civil rights period than in the period that immediately preceded the notable civil rights victories. To put the question more pointedly, even if racism continues to be a factor in the social and economic progress of some blacks, can it be used to explain the sharp increase in inner-city social dislocations since 1970? Unfortunately, no one who supports the contemporary racism thesis has provided adequate or convincing answers to this question.

Wilson then presciently bemoans (remember, he was writing in 1987) the counter-productive use of the imprecise concept of “structural racism” (which today as often referred to as “systemic racism”) to explain problems that have causes other than racism, writing that:

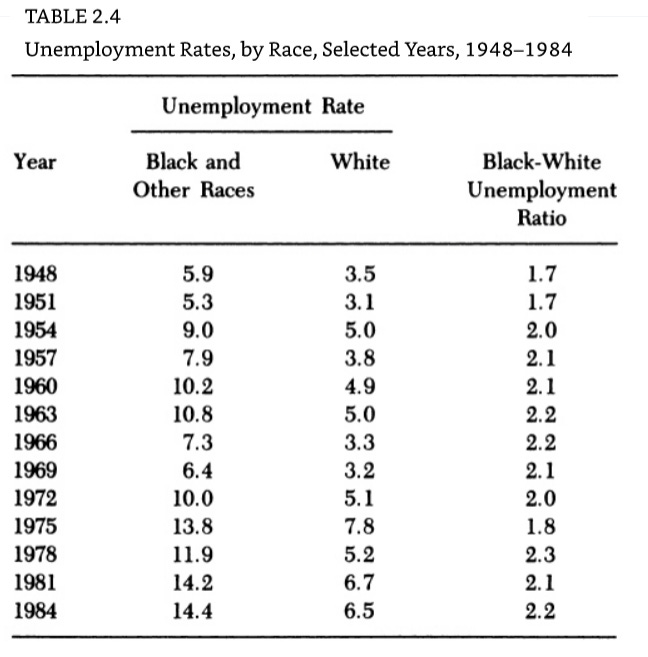

this whole question is discussed in terms of an “economic structure of racism.” In other words, complex problems in the American and worldwide economies that ostensibly have little or nothing to do with race, problems that fall heavily on much of the black population but require solutions that confront the broader issues of economic organization, are not made more understandable by associating them directly or indirectly with racism. Indeed, because this term has been used so indiscriminately, has so many different definitions, and is often relied on to cover up lack of information or knowledge of complex issues, it frequently weakens rather than enhances arguments concerning race … [P]roponents of the discrimination thesis often fail to make a distinction between the effects of historic discrimination, that is, discrimination before the middle of the twentieth century, and the effects of discrimination following that time. They therefore find it difficult to explain why the economic position of poor urban blacks actually deteriorated during the very period in which the most sweeping antidiscrimination legislation and programs were enacted and implemented. Their emphasis on discrimination becomes even more problematic in view of the economic progress of the black middle class during the same period. There is no doubt that contemporary discrimination has contributed to or aggravated the social and economic problems of the ghetto underclass. But is discrimination greater today than in 1948, when, as shown in table 2.4, black unemployment was less than half the 1980 rate, and the black-white unemployment ratio was almost one-fourth less than the 1980 ratio?

Wilson asks:

Why have the social conditions of the ghetto underclass deteriorated so rapidly in recent years? Racial discrimination is the most frequently invoked explanation, and it is undeniable that discrimination continues to aggravate the social and economic problems of poor blacks. But is discrimination really greater today than it was in 1948, when black unemployment was less than half of what it is now, and when the gap between black and white jobless rates was narrower? As for the poor black family, it apparently began to fall apart not before but after the mid-twentieth century. Until publication in 1976 of Herbert Gutman’s The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, most scholars had believed otherwise. Stimulated by the acrimonious debate over the Moynihan report, Gutman produced data demonstrating that the black family was not significantly disrupted during slavery or even during the early years of the first migration to the urban North, beginning after the turn of the century. The problems of the modern black family, he implied, were associated with modern forces. Those who cite discrimination as the root cause of poverty often fail to make a distinction between the effects of historic discrimination (i.e., discrimination prior to the mid-twentieth century) and the effects of contemporary discrimination. Thus they find it hard to explain why the economic position of the black underclass started to worsen soon after Congress enacted, and the White House began to enforce, the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. The point to be emphasized is that historic discrimination is more important than contemporary discrimination in understanding the plight of the ghetto underclass — that in any event there is more to the story than discrimination (of whichever kind). Historic discrimination certainly helped create an impoverished urban black community in the first place. In his recent A Piece of the Pie: Black and White Immigrants since 1880 (1980), Stanley Lieberson shows how, in many areas of life, including the labor market, black newcomers from the rural South were far more severely discriminated against in northern cities than were the new white immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Europe. Skin color was part of the problem but it was not all of it. The disadvantage of skin color— the fact that the dominant whites preferred whites over nonwhites— is one that blacks shared with the Japanese, Chinese, and others. Yet the experience of the Asians, who also experienced harsh discriminatory treatment in the communities where they were concentrated, but who went on to prosper in their adopted land, suggests that skin color per se was not an insuperable obstacle.

Wilson, even back in 1987, notes that the shift in emphasis of the civil rights movement away from individual rights and toward group preferences, which is so prevalent today, was evident even then:

a critical discussion of the basic assumptions associated with two liberal principles that underlie recent, but entirely different, policy approaches to problems of race, namely, equality of individual opportunity, which stresses the rights of minority individuals, and equality of group opportunity, which embodies the idea of preferential treatment for minority groups. The goals of the civil rights movement have changed considerably in the last fifteen to twenty years. This change has been reflected in the shift in emphasis from the rights of minority individuals to the preferential treatment of minority groups.

Wilson, however, rejects race-based approaches in favor of a principle that supports the equality of life chances generally, regardless of race:

However, there does exist a third liberal philosophy concerned with equality and social justice, namely, what [James S.] Fishkin has called the principle of equality of life chances … [P]rograms based on this principle would not be restrictively applied to members of certain racial or ethnic groups but would be targeted to truly disadvantaged individuals regardless of their race or ethnicity. Thus, whereas poor whites are ignored in programs of reverse discrimination based on the desire to overcome the effects of past discrimination, they would be targeted along with the truly disadvantaged minorities for preferential treatment under programs to equalize life chances by overcoming present class disadvantages. Under the principle of equality of life chances, efforts to correct family background disadvantages through such programs as income redistribution, compensatory job training, compensatory schooling, special medical services and the like would not “require any reference to past discrimination as the basis for justification.” All that would be required is that the individuals targeted for preferred treatment by objectively classified as disadvantaged in terms of the competitive resources associated with their economic-class background.

With Wilson’s understanding of the declining significance of race even in the 1980’s as background, the next essays in this series will look at the evidence that racism has declined in significance even more during the last thirty years.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6