Data on Racism – Part 1

The declining significance of race, even way back in 1980.

In this series of essays, we’ll look at data on the prevalence of racism in modern America.

I recently came across the works of Harvard Professor William Julius Wilson. In the 1980’s, he wrote extensively about the decline of racism in America, and the modern association of class, not race, with the condition of many inner-city poor, along with the need for race-neutral solutions to problems faced by all low-income citizens. In many ways, writing as he did decades ago about the steep decline of racism even then, Professor Wilson’s work was prescient, and the problems he saw with the race-focused approach to public policy have unfortunately become even more entrenched, and counter-productive. So I want to start this series of essays with an exploration of many of the points made by Professor Wilson in his book The Declining Significance of Race, first published in 1980, and his book The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, first published in 1987.

Let’s begin with The Declining Significance of Race, remembering that it was describing Professor Wilson’s views on the declining significance of race over forty years ago.

Wilson describes the thesis of his book as follows:

I now feel that many important features of black and white relations in America are not captured when the issue is defined as majority versus minority and that a preoccupation with race and racial conflict obscures fundamental problems that derive from the intersection of class with race.

Just so people are clear of what he means by “class,” he defines it this way:

Since “class” is a slippery concept that has been defined in a variety of ways in the social science literature, I should like to indicate that in this study the concept means any group of people who have more or less similar goods, services, or skills to offer for income in a given economic order and who therefore receive similar financial remuneration in the marketplace. One’s economic class position determines in major measure one’s life chances, including the chances for external living conditions and personal life experiences.

As Wilson writes:

[A]s the influence of race on minority class-stratification decreases, then, of course, class takes on greater importance in determining the life chances of minority individuals. The clear and growing class divisions among blacks today constitute a case in point. It is difficult to speak of a uniform black experience when the black population can be meaningfully stratified into groups whose members range from those who are affluent to those who are impoverished.

Even over forty years ago, there had developed a significant affluent black population, along with the enactment of our major federal civil rights law in the 1960’s. As Wilson continues:

Race relations in America have undergone fundamental changes in recent years, so much so that now the life chances of individual blacks have more to do with their economic class position than with their day-to-day encounters with whites. In earlier years the systematic efforts of whites to suppress blacks were obvious to even the most insensitive observer. Blacks were denied access to valued and scarce resources through various ingenious schemes of racial exploitation, discrimination, and segregation, schemes that were reinforced by elaborate ideologies of racism. But the situation has changed. However determinative such practices were for the previous efforts of the black population to achieve racial equality, and however significant they were in the creation of poverty-stricken ghettoes and a vast underclass of black proletarians — that massive population at the very bottom of the social class ladder plagued by poor education and low-paying, unstable jobs — they do not provide a meaningful explanation of the life chances of black Americans today.

Even as of 1980, Wilson writes that “It is clearly evident in this connection that many talented and educated blacks are now entering positions of prestige and influence at a rate comparable to or, in some situations, exceeding that of whites with equivalent qualifications. It is equally clear that the black underclass is in a hopeless state of economic stagnation, falling further and further behind the rest of society … It is also the case that class has become more important than race in determining black life- chances in the modern industrial period.”

If not racism, what was the root cause of the decreased life prospects for some blacks in 1980? As Wilson explains, it relates primarily to poor education and lower participation in the labor force:

On the one hand, poorly trained and educationally limited blacks of the inner city, including that growing number of black teenagers and young adults, see their job prospects increasingly restricted to the low-wage sector, their unemployment rates soaring to record levels (which remain high despite swings in the business cycle), their labor-force participation rates declining, their movement out of poverty slowing, and their welfare roles increasing. On the other hand, talented and educated blacks are experiencing unprecedented job opportunities in the growing government and corporate sectors, opportunities that are at least comparable to those of whites with equivalent qualifications.

Wilson quotes Lee Rainwater, another sociologist at Harvard, who observed in 1966 that:

in the hundred years since emancipation, Negroes in rural areas have been able to maintain full nuclear families almost as well as similarly situated whites … It is the move to the city that results in the very high proportion of mother-headed households. In the rural system the man continues to have important functions; it is difficult for a woman to make a crop by herself, or even with the help of other women. In the city, however, the woman can earn wages just as a man can, and she can receive welfare payments more easily than he can. In rural areas, although there may be high illegitimacy rates and high rates of marital disruption, men and women have an interest in getting together; families are headed by a husband-wife pair much more often than in the city. That pair may be much less stable than in the more prosperous segments of Negro and white communities but it is more likely to exist among rural Negroes than among urban ones.

Wilson then remarks:

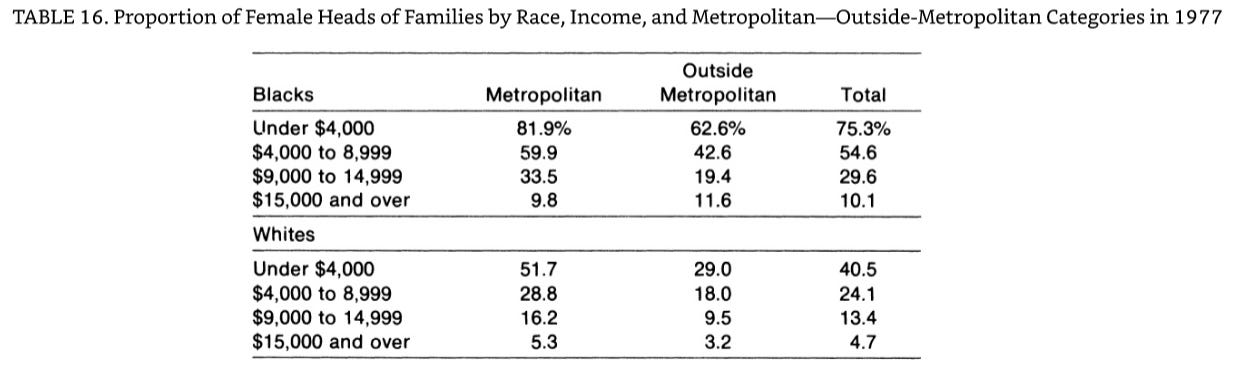

Since Rainwater made this observation, the proportion of female-headed families among blacks continues to be significantly higher in the metropolitan than in the nonmetropolitan areas in all but the highest income categories (see table 16).

Only in the higher income categories in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas is the male-headed family clearly the dominant pattern. Nine out of every ten black families whose income in 1977 was $15,000 or more are headed by men. Thus, these data dramatically reveal the powerful connection between class background and the structure of the black family.

As we’ve explored in previous essays, the overwhelming cause of disparities among people grouped by race relates to the fewer resources and attention that can be devoted to children when they are raised in only one-parent families. As Wilson wrote, back in 1980:

The essential point is that a serious effort to address the issue of the exploding number of black female-headed families, and therefore the decreasing percentage of black children living with both parents, requires that we do not define the matter solely in terms of race. It is necessary, in other words, that we recognize and acknowledge the importance of economic class position.

So, as Wilson points out, disparities that occur among some portion of the black community today stem primarily not from racism, but from poor education and poor job prospects:

And it should certainly be noted that unemployed men are more likely to leave their families than employed men. For all these reasons, it would be extremely shortsighted to assume that the problems of the lower-class black family can be satisfactorily addressed without a fundamental program of economic reform. A program that would lead to the sustained employment of ghetto men at respectable wages would be far more effective than any other conceivable effort to stabilize the ghetto family.

Wilson points out that this was recognized by prominent black commentators as early as 1968:

This theme was once again echoed in the pages of Crisis in February 1968 in an issue dedicated to the memory of W. E. B. Du Bois. Henry Lee Moon wrote, for example, “What began as a color problem at the time that Dr. Du Bois emerged as the leader of Negro protest, has become, in the last third of the Twentieth Century, basically a problem in education and economics.”

Wilson then points to speech by the late economist and former president of Clark College, Vivian W. Henderson:

In a speech delivered at a conference in honor of Du Bois at Atlanta University in October 1974 and reprinted in the February 1975 issue of Crisis, Henderson wrote, “If all racial prejudice and discrimination and all racism were erased today, all the ills brought by the process of economic class distinction and economic depression of the masses of black people would remain.”

So the key to black success was the same as the key to everyone’s success:

The economic future of blacks in the United States is bound up with that of the rest of the nation. Policies, programs, and politics designed in the future to cope with the problems of the poor and victimized will also yield benefits to blacks. In contrast, any efforts to treat blacks separately from the rest of the nation are likely to lead to frustration, heightened racial animosities, and a waste of the country’s resources and the precious resources of black people … The current economic problems of the black urban underclass cannot be sufficiently addressed by programs based on the premise that race is the major cause of those problems … In other words, policies that do not take into account the characteristics of the national economy — including its rate of growth and the nature of its demand for labor; the factors which affect industrial employment, such as technology, profit rates, and unionization; and patterns of individual and institutional migration which result from industrial shifts and transformations — will not effectively deal with the economic dislocation of poor minorities.

Wilson then revisits the same subject of the breakdown of the family in a significant portion of the black community, but circa 1980:

Once the importance of the legacy of previous discrimination is recognized, it becomes difficult to explain the gap between black and white income and employment solely, or even primarily, in terms of current discrimination … The effect of family background is most clearly seen in the field of education. The number of blacks attending colleges and universities in the United States has increased from 340,000 in 1966 to well over a million today. “Blacks who make up 11 percent of America’s population, now make up 10 percent of the 10.6 million college students,” states Clifton R. Wharton, Jr. “In one year, 1974, the percentage of Black high school graduates actually exceeded the percentage of white high school graduates going to college.” Moreover, the proportion of eighteen- to nineteen- year- old black males attending college in the 1970s has risen while the proportion of eighteen- to nineteen- year- old white males has dropped … [But] while nearly an equal percent of white and black high school graduates are entering college, the percent of young blacks graduating from high school lags significantly behind that of white high school graduates. In 1974, 85 percent of young white adults (aged twenty to twenty-four), but only 72 percent of young black adults, graduated from high school. Moreover, only 68 percent of young black adult males graduated from high school. And of those young blacks (aged eighteen to twenty-four) who were not enrolled in college and whose family income was less than $5,000, a startling 46 percent did not graduate from high school (the comparable white figure was 39 percent).

Wilson then discusses the rates at which blacks were leaving the labor force, even back in 1980:

And what is particularly distressing is the increase in the rate at which younger black men are dropping out of the labor market altogether. Among men aged 25 to 34 the black proportion of the non-labor-force participants increased from 17.0 percent in 1964 to 22.9 percent in 1976, even though their percentage of the population increased by less than 1 percent (from 11.1 to 11.5).

Even back in 1980, Wilson observes that another reason racism couldn’t be the primary cause of fewer prospects in the black community was that, even within the black community, there were great disparities. He writes:

As [Richard] Freeman has pointed out, “because of the more rapid gains achieved by black women in the postwar period, both before and after 1964, their income and occupational attainment are closer to those of white women than the economic position of black men is to that of white men. Within more narrowly defined groups of women, in fact, the statistics show that black women do almost as well as white women.” In fact, in 1977, among year-round, full-time workers, black female college graduates earned on the average slightly more ($12,740) than their white counterparts ($12,456), whereas the average earnings of black and white female high school graduates were nearly equal — $8,557 for blacks and $8,602 for whites. And for those aged 25 to 29 the average earnings of white female college graduates was 93 percent ($10,906) that of comparable black females ($11,756), whereas white female high school graduates earned a little more ($8,817) than their black counterparts ($ 8,422).

As Wilson summarizes his conclusions:

Accordingly, the mobility pattern of blacks is consistent with the view that in the modern industrial period economic class has become more important than race in predetermining occupational mobility and job placement. In the economic realm, the black experience has moved historically from economic racial oppression experienced by virtually all African Americans to a situation in which the black poor has fallen further and further behind higher-income African Americans … By analyzing the 1940 and 1990 Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) data sets (a large, nationally representative sample of the occupational attainment of black and white males in all sectors of the labor force), [Arthur] Sakamoto and Jessie] Tzeng were able to test my thesis over a broader time span. They found that whereas race was generally more important than class in determining occupational attainment among blacks during the industrial period of 1940, class was clearly more important than race in determining occupational attainment among black men during the modern industrial period of 1990. Their results “indicate that the net disadvantage of being black is substantially greater in the industrial period than in the modern industrial period.” … [In 1990] education was a much more significant factor than being black … “These results,” state Sakamoto and Tzeng, “support Wilson’s thesis of the declining significance of race, and they are consistent with his claim that in the modern industrial period after the civil rights movement, ‘economic class position [is] more important than race in determining black chances for occupational mobility.’”

Wilson, in an afterword contained in a subsequent edition of his book, also remarks that:

the progress of black college graduates was substantially greater, with incomes that changed from fewer than 6 percent of comparable whites’ incomes in 1974 to matching the income of their white counterparts in 1981. Even more spectacular, “black college graduates obtain more prestigious posts than their white counterparts.” These findings are consistent with the data I presented on the black/white income gap of younger college graduates in the second edition of The Declining Significance of Race.

Wilson then begins to explore a subject he would return to in his subsequent book The Truly Disadvantaged, namely the widening gap among the poorer and better-off segments of the black community:

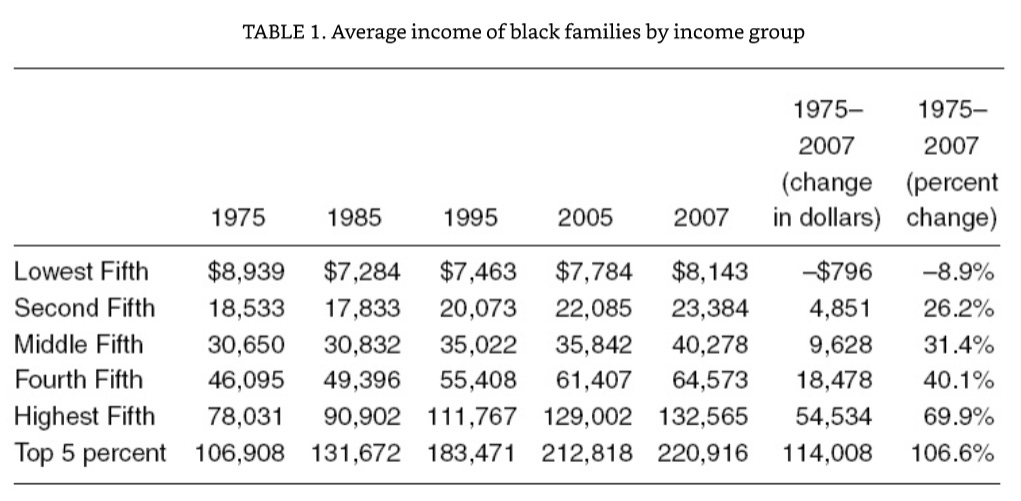

One of the basic arguments of The Declining Significance of Race is that there has been a deepening economic schism as reflected in a widening gap between lower- income and higher-income black families. In light of more recent data, not only has the family income gap between poorer and better-off African Americans continued to widen, but the situation of the bottom fifth of black families has deteriorated since 1975 (see table 1).

In 2007, 45.6 percent of all poor blacks had incomes below 50 percent of the poverty line. Overall, poor black families fell below the poverty line by an average of $9,266 in 2007, a depth of poverty exceeding that of all other racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Regardless of the reversal of the relative income gains of younger educated blacks reported in the previous section, the income gap between the haves and have-nots in the African American population continues to grow.

Interestingly, Wilson points out in his subsequent book, The Truly Disadvantaged, how this increasing gap between the have and have-nots in the black community is made worse by affirmative action programs themselves, which disproportionately help blacks who are already better-off:

[T]he competitive resources developed by the advantaged minority members— resources that flow directly from the family stability, schooling, income, and peer groups that their parents have been able to provide— result in their benefiting disproportionately from policies that promote the rights of minority individuals by removing artificial barriers to valued positions … [I]f minority members from the most advantaged families profit disproportionately from policies based on the principle of equality of individual opportunity, they also reap disproportionate benefits from policies of affirmative action based solely on their group membership. This is because advantaged minority members are likely to be disproportionately represented among those of their racial group most qualified for valued positions, such as college admissions, higher paying jobs, and promotions. Thus, if policies of preferential treatment for such positions are developed in terms of racial group membership rather than the real disadvantages suffered by individuals, then these policies will further improve the opportunities of the advantaged without necessarily addressing the problems of the truly disadvantaged such as the ghetto underclass.

Finally, Wilson points out that while the increased life prospects of black women, as demonstrated by their educational achievement, shows the declining significance of race, the fact that black men did not experience the same educational achievement also helps explain the continued dominance of single-parent families in the black community, as black men without higher education are not as attractive marriage partners. Wilson writes:

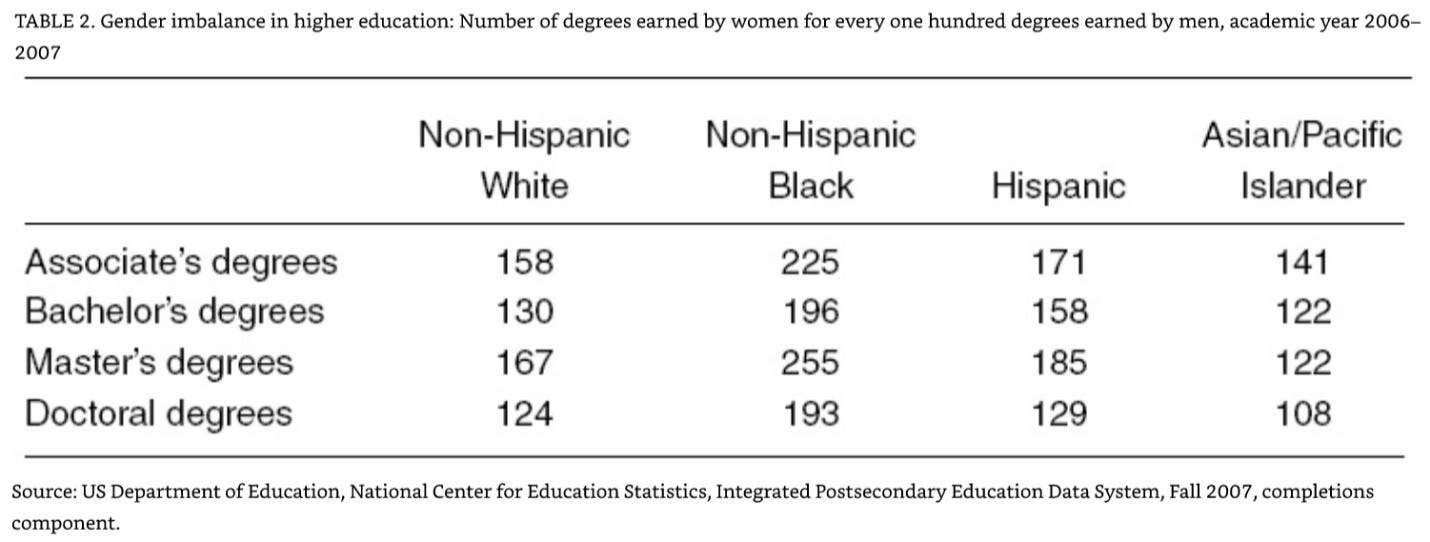

What has also changed since I wrote The Declining Significance of Race is that the black class structure increasingly represents an inversion of the gender effect on class among African Americans, especially among younger blacks, as males have fallen behind females on a number of socioeconomic indicators: employment rates, high school completion rates, and average income, with some of the sharpest discrepancies at the lower end of the income hierarchy. Black women have also far outpaced black men in college completion in recent years. Despite the fact that the gender gap in college degree attainment is increasing across all racial groups, with women generally exceeding men in rates of college completion, this discrepancy is particularly acute among African Americans. That gap has widened steadily over the past twenty-five years. In 1979, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees earned by black men, 144 were earned by black women. In 2006 to 2007, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees conferred on black men, 196 were conferred on black women— nearly a two-to-one ratio. To put this gap into a larger context, for every 100 bachelor’s degrees earned by white men and every 100 earned by Hispanic men, white women earned 130 and Hispanic women earned 158, respectively (see table 2).

The gap widens higher up on the educational ladder. For every 100 master’s degrees and 100 doctorates earned by black men, black women earned 255 and 193, respectively. These ratios have huge implications for the social organization of the black community. A discussion of the black class structure today has to include a gender component to show the increasing proportion of black women and decreasing proportion of black men in higher socioeconomic positions.

In the next essay, we’ll look at some of the key observations made by Professor Wilson in his 1987 book, The Truly Disadvantaged.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6