In previous essays we examined how and why the labor force participation rate has dropped so low, especially among younger people of prime working age. Now let’s explore what’s happening among teenagers and seniors.

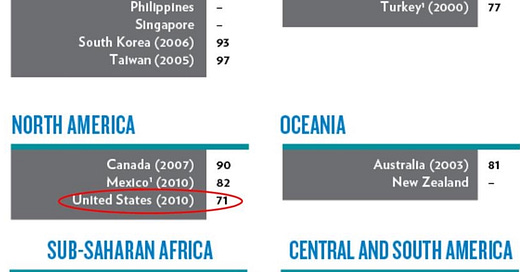

Among industrialized countries, the United States has among the lowest rate of children under 18 in households in which the household head is employed, meaning fewer children in the United States will be exposed to an employment routine as a model for their own behavior.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal, a landmark 2024 Harvard study from 2024 found that poor children who grow up in a neighborhood where more parents have jobs are better off economically as adults:

Analyzing data covering a near universe of Americans born from 1978 to 1992, the researchers found that when employment among the poor parents of children in a community improves, those children are better off economically as adults. It is a dynamic that some researchers have suspected, but that has never been shown systematically. Importantly, it doesn’t rely on whether a child’s own parents are employed: Outcomes also improve for children who simply grow up in a neighborhood where more parents have jobs. In other words, their own parents might be unemployed, but if their schoolmates’ parents work, their outcomes will be better. The dynamic works in reverse too: In places where parental employment deteriorates, the opposite happens—children do worse as adults. “Growing up in a community where employment rates are higher for people in your race and class—if those employment rates are higher, the kids who grew up in those environments do better in the long run,” said Chetty, who directs Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based institute that studies how to improve upward mobility.

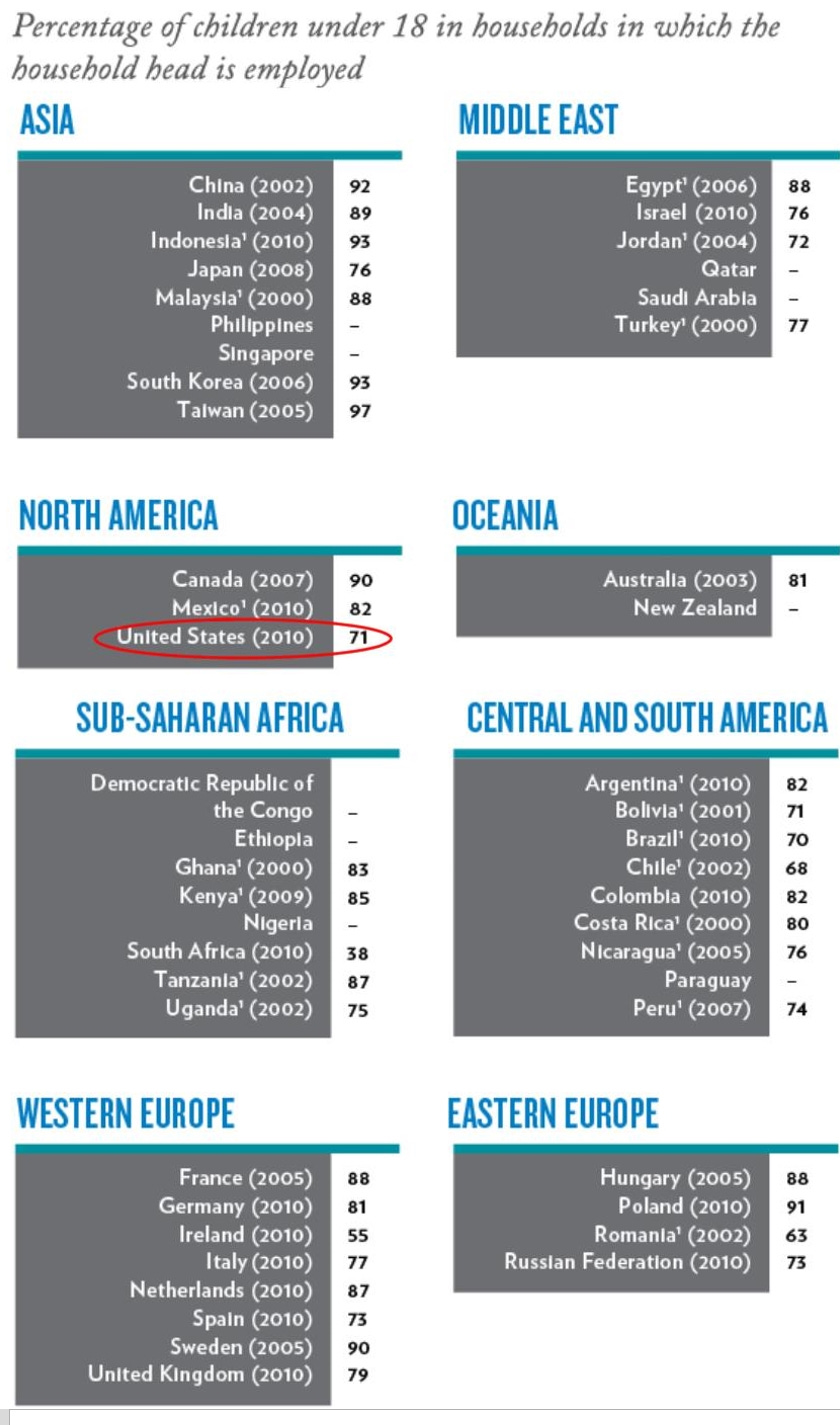

About one-third of children in poverty have no people working in their family.

Less than ten percent of people in poverty who aren’t working say the reason they’re not working is because they were looking for and could not find work.

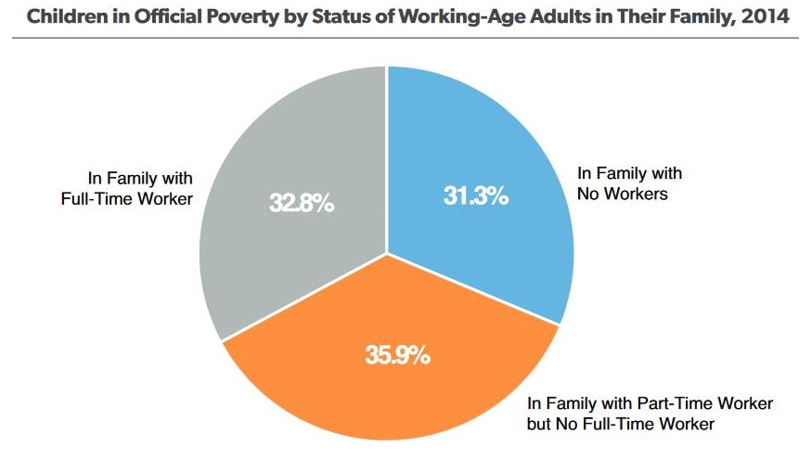

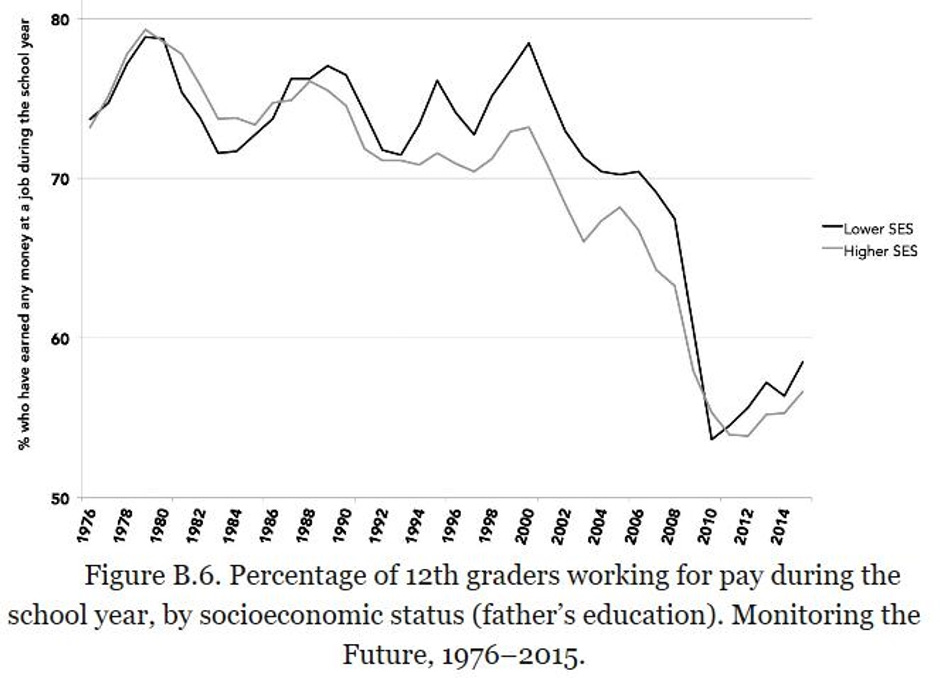

The percentage of high school students who earn money from paid work has dropped significantly.

That drop has occurred among high school students whose fathers come from both high and low socioeconomic statuses.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project have found that “the reasons for declining teen labor force participation seem to reflect increasing time spent in school during the summer as well as a decline in labor force participation while in school during the academic year.”

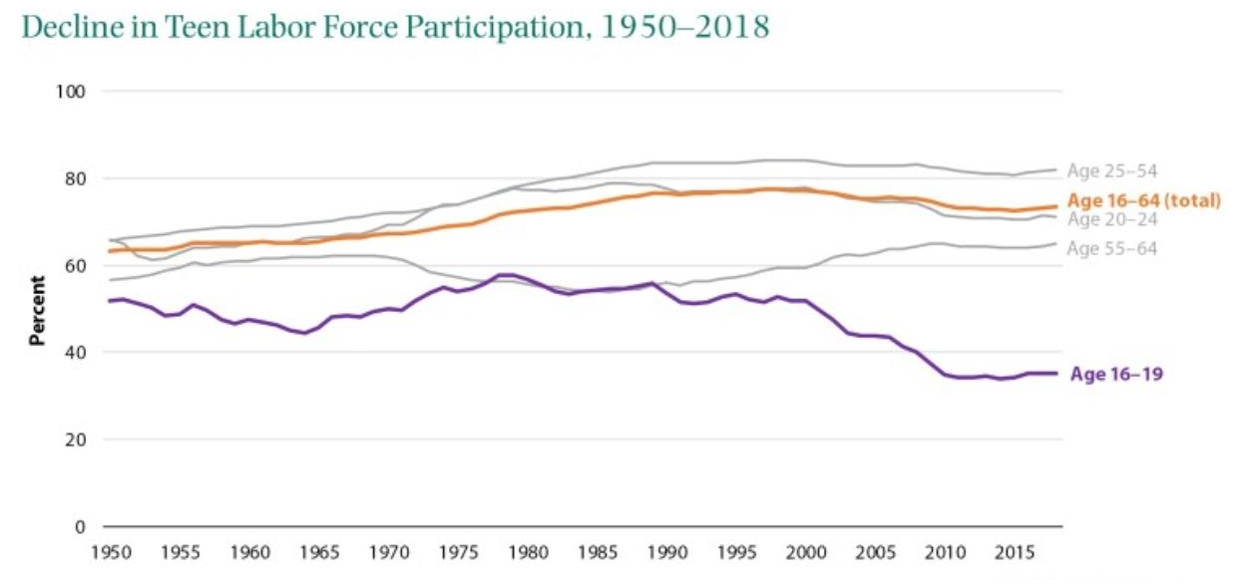

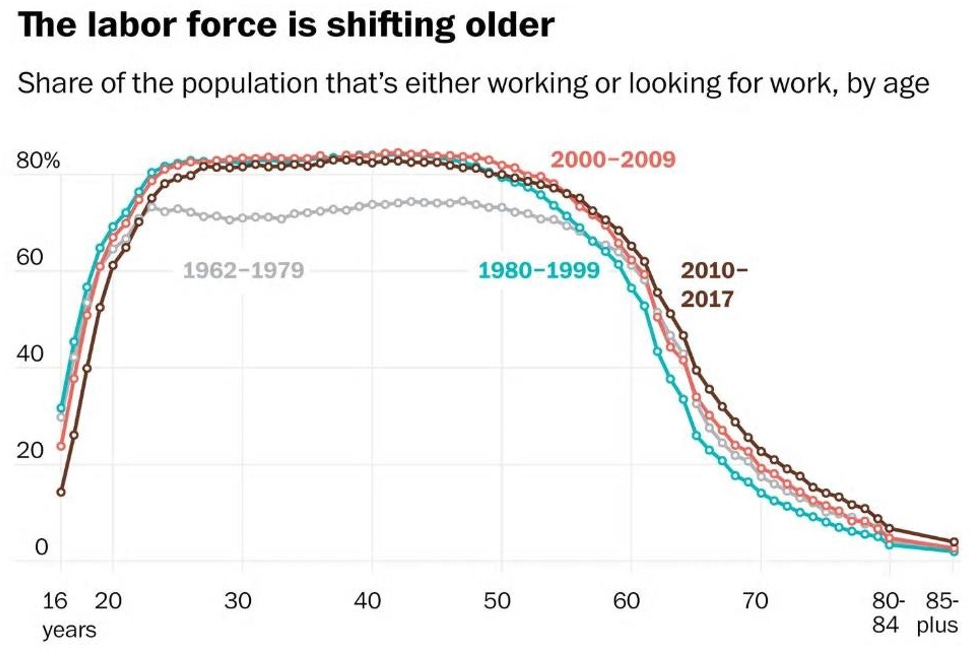

While the labor force participation rate among younger people is declining in America …

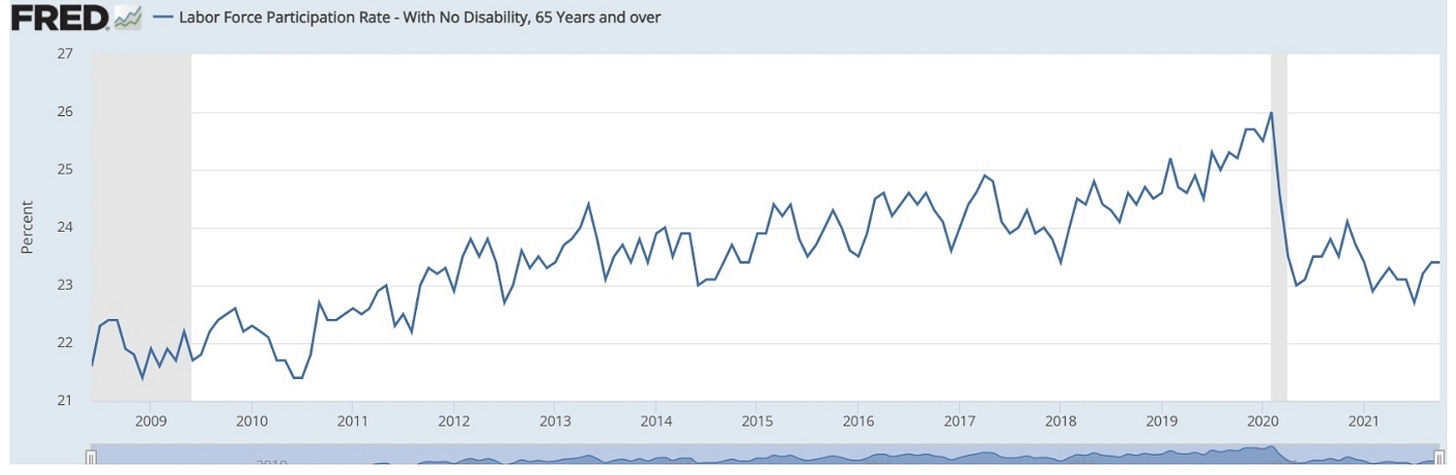

… the labor force participation rate among the older generation was increasing (until the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020).

The labor force generally is shifting toward older people.

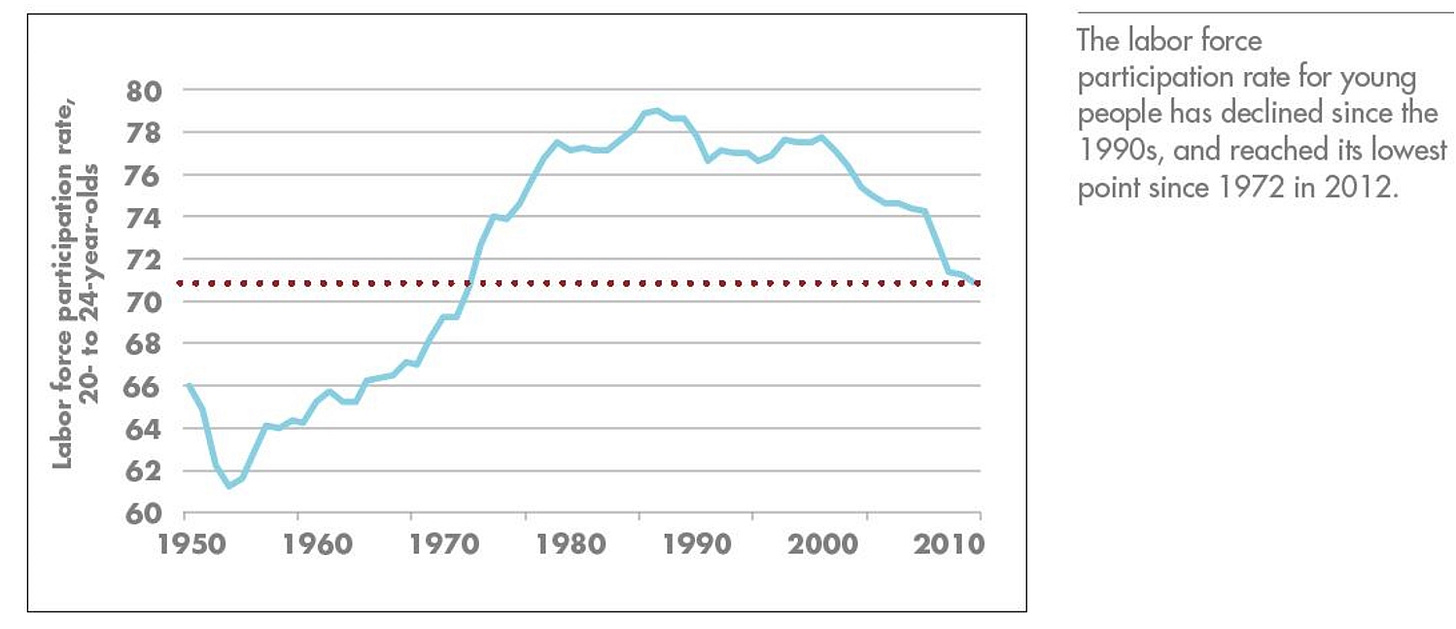

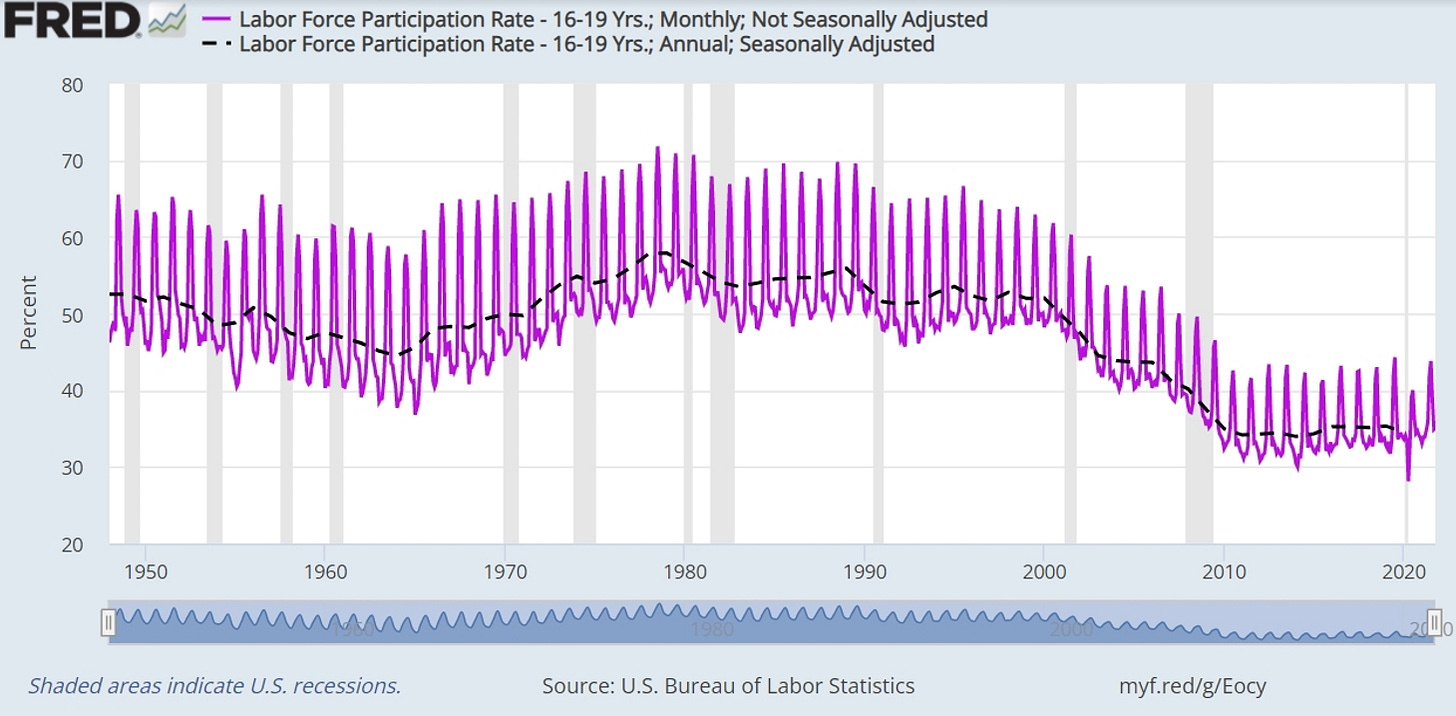

Younger people were participating somewhat more in the labor force in the years since 2015, when the economy recovered. But overall, as the below data from the Federal Reserve shows, “Teens no longer participate in the labor market with the same vigor as they did up to 1978.”

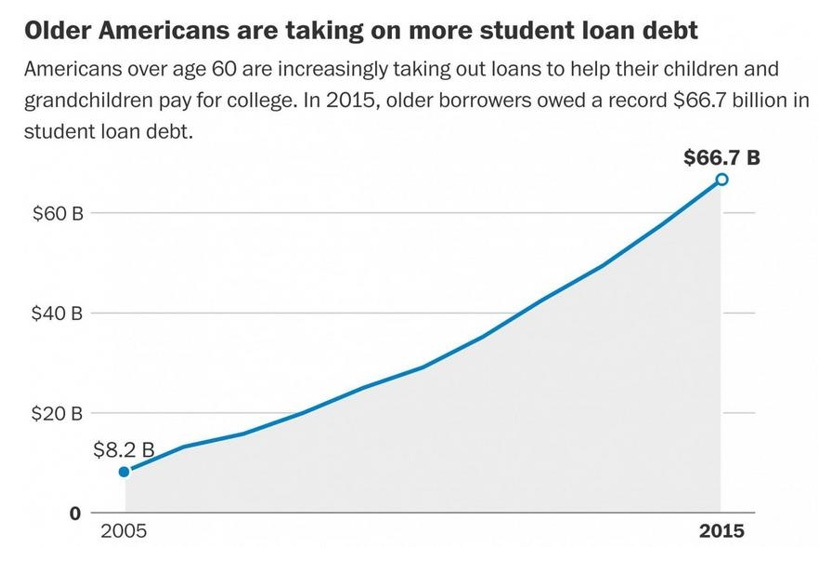

The amount of student debt older people are taking on (on behalf of their children and grandchildren) has quadrupled.

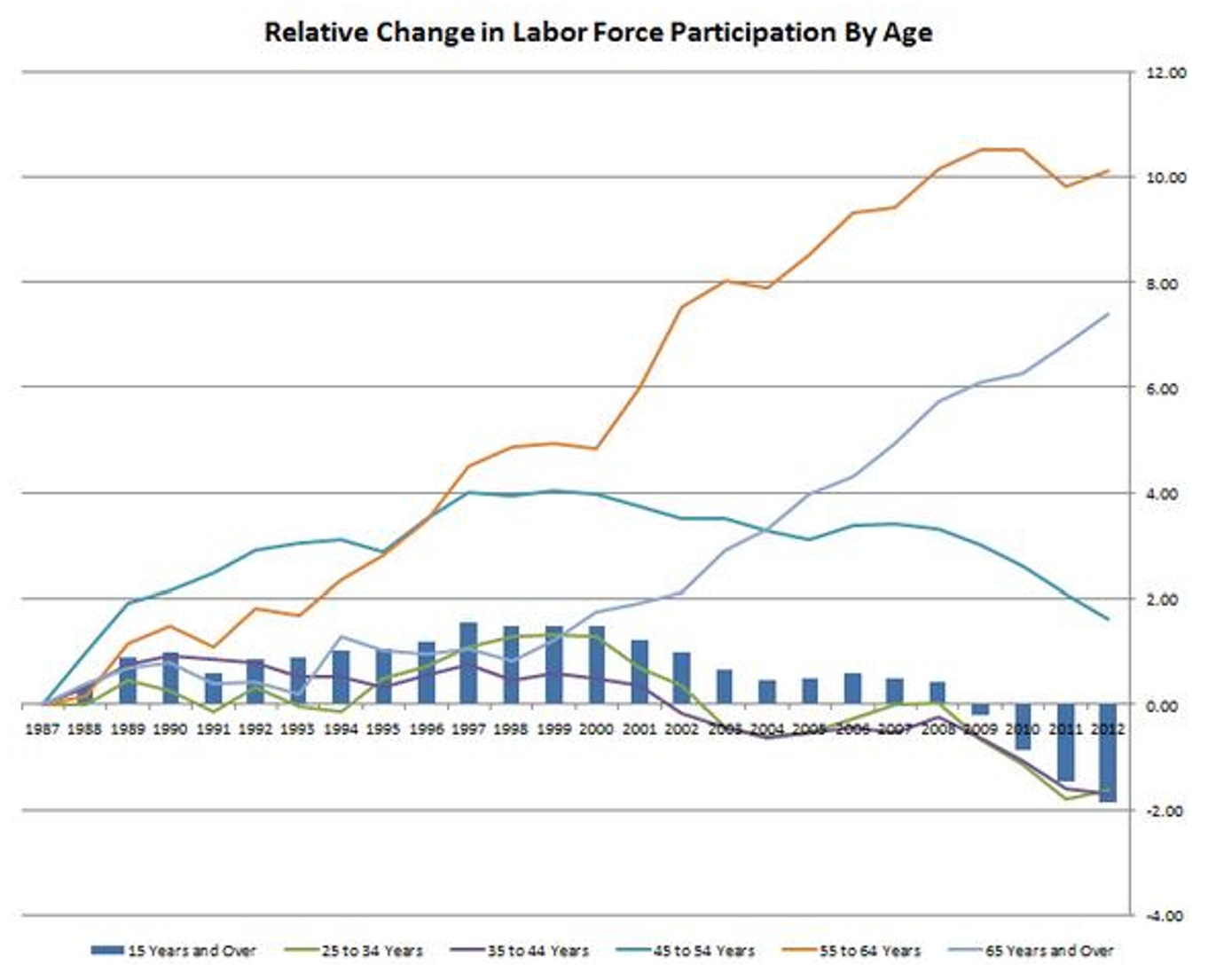

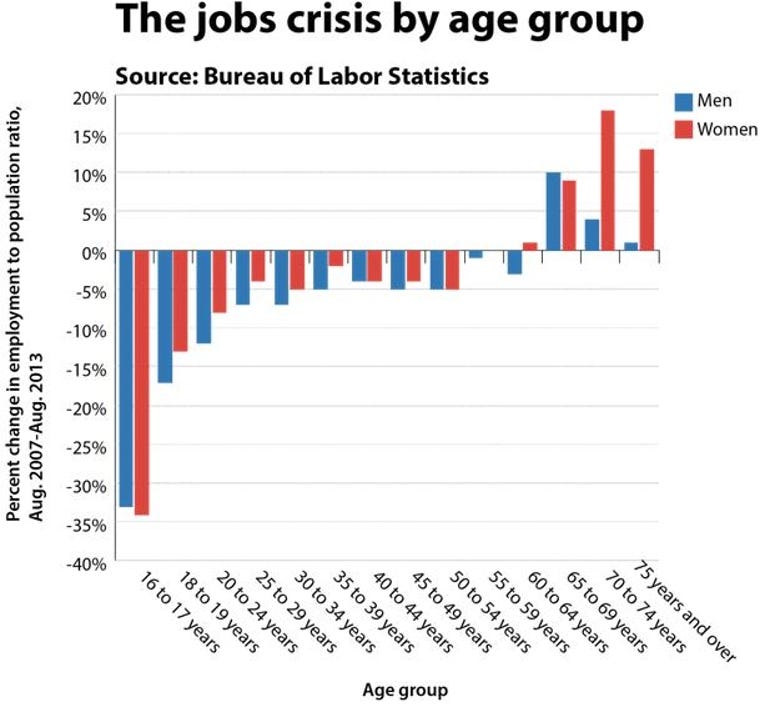

A generation gap has grown in which younger people have been leaving the labor force in greater percentages, and older people have been staying in the labor force in greater percentages, for many years now.

That accelerated trend over the years is shown here.

Older workers are not “crowding out” younger workers, as today there are more job opening created by retirements per young person. Even so, today in the United States, the labor force participation rate among people over age 65 is higher than in most of the rest of the world.

And only about a tenth of the overall increase in entitlement recipience can be accounted for by the increase in America’s over-65 population. As Nicholas Eberstadt writes in A Nation of Takers: America’s Entitlement Epidemic, “rough calculations suggest that only about a tenth of the overall increase in the prevalence of reported entitlement recipience between the early 1980s and the Obama administration can be accounted for by the increase in America’s 65-plus population. The rest has been due, in the main, to an increasing proclivity by younger households to seek and obtain entitlement benefits.”

In the next essay, we’ll look at the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the trends in labor force participation we’ve addressed so far.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5