The Diminishing American Labor Force – Part 2

What’s driving the decreasing labor force participation rate?

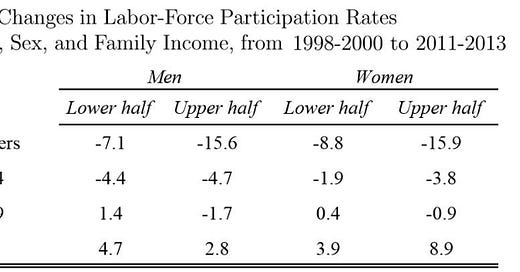

As explored in the last essay, the labor force participation rate has fallen in America. But in recent years labor force participation has fallen especially among teenagers and those ages 20 to 34, and disproportionately among young people from higher income groups.

People are also generally spending more of their free time engaging in personal care (including sleep) and leisure activities (mainly video-related activities).

Nicholas Eberstandt described results from the American Time Use Survey in 2021, and his analysis is worth quoting at length:

Thanks to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we have detailed, self-reported information each year on how roughly 10,000 adult respondents spend their days—from the moment they wake until they sleep.1 These surveyed Americans include prime-age men who are not in labor force (or “NILF” to social scientists), ordinarily in their peak employment years, who are neither working nor looking for work. By examining the self-reported patterns of daily life of these grown men who do not have and are not seeking jobs, we may gain insights into the work-free existence that some UBI advocates hold to be a positive end in its own right. Even without a UBI, America has seen an extraordinary increase in the ranks of workless, prime-age men over the past two decades … Although the number of prime-age NILF men held steady at roughly one million throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, that total has exploded since. Just before the pandemic hit, almost 7 million civilian, non-institutionalized men between the ages of 25 and 54 were out of the workforce altogether. For over half a century, the growth in America’s population of prime-age NILF men has been astonishingly steady and regular, rising by roughly 10,000 each month from 1965 to 2019. Just how and why so many men in the prime of life should now be swept up in this flight from work is a matter of continuing scholarly research and debate. For now, it will suffice to observe that these many millions of men already draw on resources sufficient to afford a work-free existence.

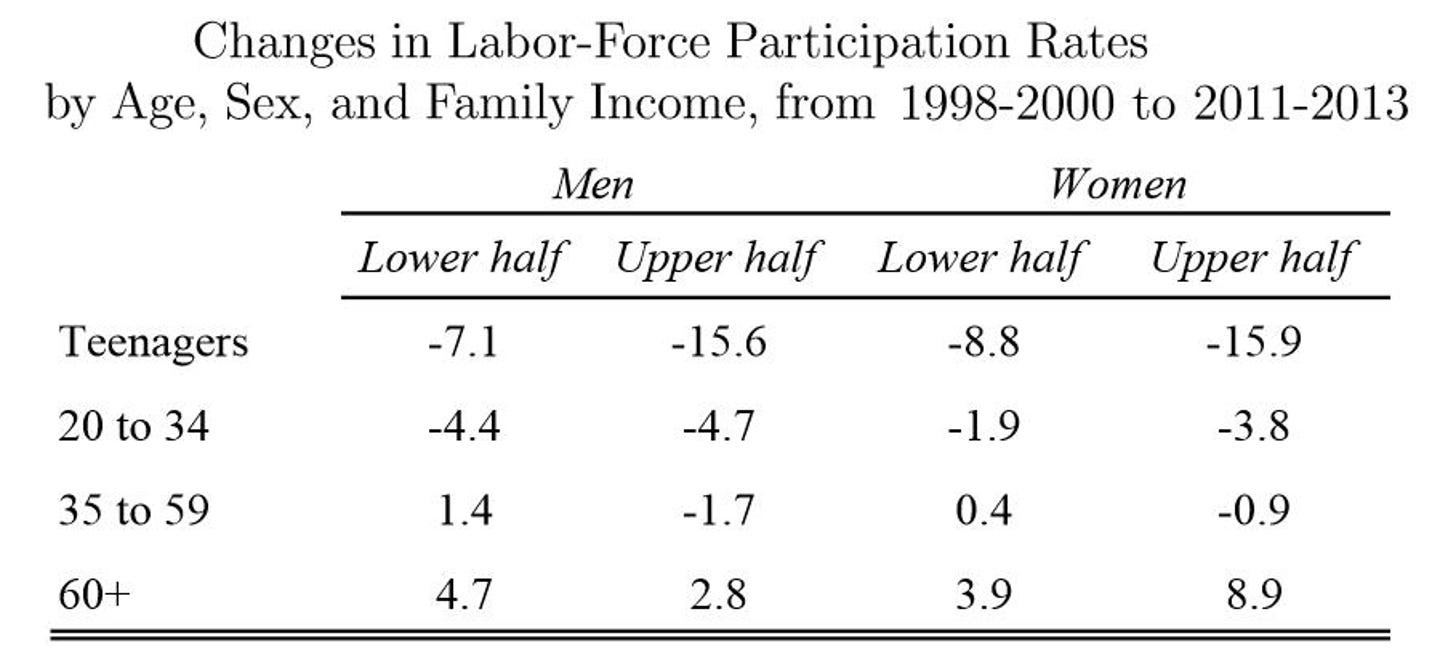

So what do these work-free men do with all their time? We can best answer that question by comparing their self-reported activities with those of other 25-54 year-old Americans surveyed by ATUS: employed men; unemployed men; and employed women. The “employed” men and women in this survey, incidentally, are not necessarily full-time workers—even men and women very slightly employed are counted in this category. The “unemployed,” for their part, are persons currently jobless who want work and still consider themselves part of the labor force. Though imposing in absolute terms, prime-age NILF men account for less than 3% of pre-COVID America’s adult population, and thus for a small number of observations in any single ATUS survey. For this reason, we pooled the five most recent years of the survey—2015 through 2019—to glean statistically meaningful results from the differences in time use between the prime-age male NILFs and their working counterparts. Major differences in time use patterns distinguish prime-age male NILFs from other men and women their age (see Table 1 below). It is not surprising that NILF men report much less paid work than their peers—an average of just 12 minutes per day, nearly six hours a day less than employed men, and almost five hours a day less than employed women, but also close to an hour a day less than unemployed men. Perhaps more surprisingly, their time freed from work is not repurposed into helping out around the home, such as doing housework, cooking, and other tasks of home maintenance. In fact, they devote significantly less time to such home chores than unemployed men—less, too, than women with jobs. NILF men also spend much less time helping to care for other household members than working women—less time, as well, than unemployed men.

Apart from work, by far the biggest difference between the daily schedules of NILF men and everyone else comes in what the ATUS calls “socializing, relaxing, and leisure,” a category that encompasses a range of activities, from listening to music to visiting a museum to attending a party. On average, prime-age NILF men spend almost seven and a half hours a day in such diversions—over four hours a day more than working women, nearly four hours a day more than working men, and over an hour more than jobless men looking for work. But NILF turns out to be a catch-all category that merges two very different populations. One of them is adult students, out of the labor force for training to improve their job prospects upon return. The other is a group British parlance calls “NEET”—an acronym for “neither employed nor in education or training.” The NEETs are in effect complete labor force dropouts. And in contemporary America, the overwhelming majority of prime-age male NILFs are NEETs: in the years 2015-19, according to Census Bureau data, fewer than one in six NILFs was an adult student. In the lead-up to the COVID pandemic, this meant one in 10 prime-age men was neither working, nor looking for work, nor seeking the skills that might help them return to the workforce. If we disaggregate prime-age NILFs into NEETs and adult students, two strikingly different ways of life are revealed.

[S]elf-identified prime-age NEET men spend about seven and a half hours a day in “leisure activities.” That works out to about 2,700 hours a year—almost 1,600 hours a year more than working women, nearly 1,400 hours a year more than working men, and remarkably enough, over 450 hours a year more than unemployed men. Economists and other social scientists often use “leisure” and “free time” interchangeably, but this is a mistake. The “leisure” activities that NILFs and NEETs indulge in are generally not the sort of higher pursuits that, for example, Josef Pieper had in mind in his classic Leisure: The Basis of Culture. The overwhelming majority of this “leisure” is screen time: television, internet, DVDs, and all the rest. NEET men reported an average of over five hours a day in front of screens—nearly 1,900 hours a year, almost equivalent to the time commitment of a full-time job. ATUS does not ask specifically about video games; if it did, even more NEET screen time commitment would almost certainly be recorded. To go by the time-use surveys, prime-age men without work who are not looking for jobs and not engaged in training spend almost three times as many hours in front of screens as working women and well over twice as many as working men. Strikingly, they also report over 300 hours more screen time per year than their unemployed counterparts—men likewise jobless but who want to get back to work.

I recall several years ago playing a video game myself, in which my character was killed on the game’s virtual battlefield by someone who used “welfarecheck” as his gamertag (a gamertag is like an email address for people who play video games). I thought it was funny at the time, but little did I know it portended a grand trend in labor force non-participation. Incidentally, while I prepared this essay I checked the database of Xbox gamertags and was partially relieved to find that only two people are so bold as to openly declare their dependency status in their video game self-descriptions.

Government welfare checks are said to go to people “in poverty,” but to provide more context to this situation it’s worth assessing what it actually means for someone to be living “in poverty” under official government definitions of the term. To that end, it’s useful to keep in mind that even 15 years ago a large majority of those “in poverty,” according to the Census Bureau, had cable or satellite television, a DVD player, and a video game system, along with cars, microwave ovens, air conditioning, and cell phones. Advancing technology has generally allowed the same types of consumer goods (such as microwaves, air conditioning, personal digital devices, computers, and cell phones) to be readily available to the rich and poor alike.

Over the last ten years, Americans generally have come to spend 8 percent more time watching television, and 5 percent less time working.

Researchers have found that video games occupy an increasing amount of the leisure time of the unemployed:

During the period 2004-15, approximately 60 percent of the 2.3 hours of increased leisure time per week for young men was spent playing video games, while younger women and older men and women spent negligible extra leisure time in this way. These data are drawn from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS). In all, young men's time playing video games increased by 99 hours per year from 2004 to 2015, a 50 percent increase. The researchers document that time spent playing video games is very sensitive to total leisure time for younger men, but not for other demographic groups such as younger women or older men. They estimate that innovations to recreational computing and video games since 2004 can explain on the order of half the increase in leisure for younger men, and could explain a decline in work hours of 1.5 to 3.0 percent, or 30 to 60 hours per year.

The Economist points out that:

The single biggest new media habit to be formed during the pandemic appears to be gaming. The extra hour per week that people spent gaming last year represented the largest percentage increase of any media category. And unlike other lockdown hobbies, it is showing no sign of falling away as life gets back to normal. It has become “a sticky habit”, says Craig Chapple of Sensor Tower. He finds that last year people installed 56.2bn gaming apps, a third more than in 2019 (and three times the rate of increase the previous year). The easing of lockdowns is not denting the habit: the first quarter of 2021 saw more installations than any quarter of 2020. Roblox, a sprawling platform on which people make and share their own basic games, reported that in the first quarter of this year players spent nearly 10bn hours on the platform, nearly twice as much time as they spent in the same period in 2020 … [W]hereas all other generations of Americans named television and films as their favourite form of home entertainment, Generation Z ranked them last, after video games, music, web browsing and social media.

And the labor market data firm Emsi found the following:

Why the dramatic shift to part-time work, even during a time defined by prosperity and opportunity? One short and surprising answer is our second topic: video games. Yes, really. According to NBER research, the decrease in hours worked for men ages 21-30 exactly mirrored the increase in video game hours played. On average, males ages 21-30 worked over 200 fewer hours in 2015 than they did in 2000 (a 12% decline). They simultaneously upped their leisure hours, 75% of which were spent playing video and computer games. Many of these men do not have a bachelor’s degree, and the data shows they are postponing marriage, child rearing and home buying until their 30s.

The story of how video games came to be is a dynamic story of hard work, initiative, and ingenuity by the many people who made the dramatic scientific and technological contributions that made video games possible over the last fifty years. Ironically, those achievements might be encouraging another fifty years of increasingly idle time playing video games.

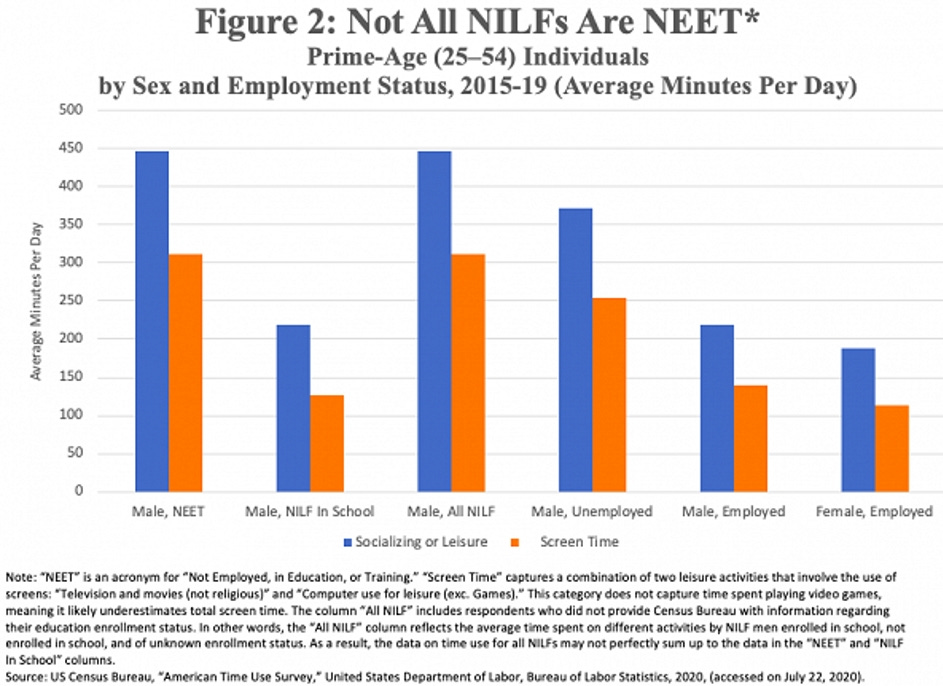

And finally, people who aren’t working aren’t even doing as many household chores as they used to. Over the past century, household work-saving appliances have become widespread, and the numbers of hours per week devoted to household chores has plummeted (and this chart only goes up to 1989).

In the next essay, we’ll focus on what kids under 18 are doing, and how that contrasts with what their grandparents’ generation is doing.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5